OBJECTIVES

Contrast food insecurity and hunger.

Discuss coping strategies associated with food insecurity that complicate disease management.

Identify risk factors for food insecurity and describe its epidemiology.

Discuss the nutritional, behavioral, and mental health impacts of food insecurity.

Identify challenges to providing care to food insecure patients and strategies that can help address these challenges in the clinical setting.

Ms. Walker is a 48-year-old woman with a history of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and depression. Her last hemoglobin A1c was 9.0%. She seems poorly engaged with her diabetes care, taking her medications intermittently, and infrequently adhering to a diabetic diet. She tells you that she frequently has difficulty making ends meet. Sometimes, rice is the only food she can afford to eat. You suspect her food insecurity is complicating her diabetes management.

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity, or the inability to reliably access safe and nutritious food, has important health consequences. Food insecurity has an impact on health through nutritional, behavioral, and mental health pathways. Food insecure children and adults have higher rates of acute and chronic illness and higher health-care utilization. Management of chronic, diet-sensitive diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and congestive heart failure, is particularly challenging in the context of food insecurity. This chapter explores the complicated relationships between food insecurity and illness with a focus on the issue in the United States and presents strategies to improve the care of food insecure patients.

DEFINITION AND PATTERNS OF FOOD INSECURITY

The most commonly accepted definition of food security and food insecurity comes from a 1990 report by the Life Sciences Research Office (LSRO)1:

Food security was defined … as access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life and includes at a minimum: a) the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and b) the assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g., without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, and other coping strategies). Food insecurity exists whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain.

In the United States, food insecurity generally implies that access to adequate food is limited by a lack of money and other resources. Globally, food insecurity may be due to other factors such as political unrest. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization defines food security as existing “when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” Food must be consistently available, accessible, and useable.2

Food insecurity is a concept distinct from the physical sensation of hunger. According to the LSRO,1 “Hunger (in its meaning of the uneasy or painful sensation caused by a lack of food) and malnutrition are potential, although not necessary, consequences of food insecurity.” Although the term “food insecurity” may obscure the tragedy of hunger, the term includes the coping strategies that households employ to avoid the physical sensations of hunger. Understanding these strategies makes clear the health and public health consequences of food insecurity (Box 26-1).

Box 26-1. Food Insecurity Coping Strategies

Shifting dietary intake to low-cost, highly filling foods (such as refined carbohydrates).

Reducing dietary variety.

Binge eating and avoiding food waste when food is available.

Skipping meals or reducing dietary intake when food is unavailable.

Shopping strategies to improve the affordability of food (buying produce in season, using coupons, taking advantage of sales, etc.).

Enrollment in federal nutrition programs (such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called “Food Stamps); the National School Lunch Program (NSLP); or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Utilizing the hunger safety net, which includes food pantries; soup kitchens; community dining; and less formal food support from religious institutions, friends, and family.

Every year in the United States, the Department of Agriculture reports the prevalence of three categories of food security: food security, low food security, and very low food security.3 Households with low or very low food security are considered “food insecure.” In general, people living in households with low food security report difficulty accessing food and the need to reduce diet quality in order to compensate for inadequate food budgets, but typically have not reduced their quantity of food. People living in households with very low food security experience reductions in their food intake and disruption of their normal eating patterns because of a lack of money or other resources for food.

In the developed world, and often in the developing world as well, food insecurity is cyclic and episodic. That is, episodes of food adequacy are punctuated by discrete episodes of food scarcity because of particular economic stresses. Households may confront an episode of food scarcity resulting from a variety of life stressors: for example, periodic, unforeseen expenditures (such as an acute medical condition or a car repair); an increase in necessary household expenditures (such as the need for heating in the winter, or to feed children in the summer when school-based access to free or reduced-price lunch declines); or, predictably at the end of the month, if household income is not adequate to cover food requirements.4

The typical food insecure household in the United States experiences food scarcity during 7 months of the year, with each episode lasting for a few days.3 The cyclic nature of food scarcity in the food insecure household and its resulting fluctuations in dietary intake make clinical care of food insecure patients with chronic disease particularly challenging.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 2013, one in seven US households (or 14.3% of all households) reported food insecurity. These households included 33.3 million adults and 15.8 million children, of whom 12.2 million adults and 765,000 children lived in very low food secure households.3 In safety-net outpatient institutions in the United States (such as Federally Qualified Health Centers), the prevalence of food insecurity often approaches 50%.

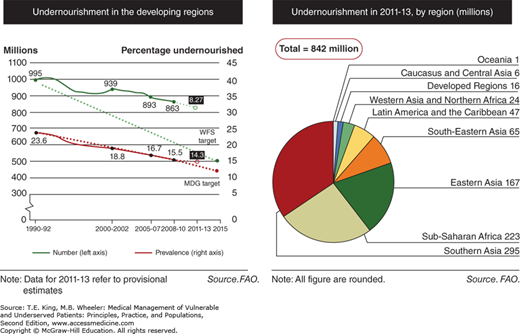

Worldwide, 842 million people (one-eighth of the world population) are estimated to be food insecure,5 with the vast majority living in developing regions. As poverty has declined and food production increased over the past several decades, the global burden of food insecurity has declined (Figure 26-1).

Figure 26-1.

Left: Undernourishment in the developing regions: actual progress and target achievement trajectories toward the MDG and WFS targets. The estimated number of undernourished people has continued to decline; however, the rate of progress is insufficient to reach MDG and WFS goals for hunger reduction. Right: The changing distribution of hunger in the world: number and share of undernourished by region, 2011–2013. Overall, there has been a reduction in the number of undernourished people over the past two decades; different rates of progress across regions have led to changes in the distribution of undernourished people in the world. Most of the world’s undernourished people are found in Southern Asia, closely followed by sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Asia. MDG, Millennium Development Goal; WFS, World Food Summit. (Adapted from FAO, IFAD and WFP. The State of Food Insecurity in the World. The Multiple Dimensions of Food Security. Rome: FAO, 2013.)

RISK FACTORS FOR FOOD INSECURITY

Ms. Walker has two children at home and is divorced. She works the night shift in a 24-hour diner. She tells her primary care provider (PCP) that she has difficulty balancing her work with parenting. In particular, she is finding it difficult to purchase and prepare healthful food. When her food budget is particularly short, she serves her children first and eats herself only what is left over. She has recently started smoking again, which she says helps her cope with the stress.

The root causes of food insecurity are highly complex and include both personal vulnerabilities (individual risk factors) and structural factors.6

In the United States, the strongest risk factors for food insecurity include having children in the household, low household income, and racial/ethnic minority status (black or Latino).1 Single-parent households are at the highest risk for food insecurity. More than a third of all households with children headed by a single woman in the United States are food insecure.

Although poverty is highly associated with food insecurity, it is not synonymous with food insecurity. Almost 60% of households with incomes below the US federal poverty level in 2012 did not report food insecurity, while almost 7% of households with incomes greater than 185% of the US federal poverty level did report food insecurity.1 Food insecure households are more likely to have experienced a recent event stressing the household budget, such as loss of employment, addition of a household member, or reduced access to federal nutrition benefits.2,7 In addition, some households have specific financial obligations that drain money from food budgets. For example, many immigrant households regularly send money to their country of origin to support family members (see Chapter 29). Other households must shoulder high out-of-pocket health-care expenditures.

Food insecure households report difficult financial choices between paying for food and paying for health care, utilities, transportation, housing, and education. Why are these necessities frequently prioritized over food? First, money that might otherwise be saved for food purchases in the near future are often deferred to other needs because food expenditures can be spread throughout the month. Second, the presence of a safety net for food (relatives/friends, food pantries, etc.) may allow for prioritization of other expenses. Finally, the ability to reduce food budgets by reducing food quality allows flexibility in the food budget that is not present in other parts of the budget.

Mental illness, tobacco use, and chronic illness place people at risk for food insecurity. Mental illness is tightly associated with food insecurity across the lifespan. It is likely that this relationship is bidirectional. In other words, food insecurity predisposes people to mental illness through both stress and micronutrient deficiency pathways; at the same time, mental illness predisposes people to food insecurity through its impact on employability and high-level executive function. The association between mental illness and food insecurity has been well documented among children, adolescents, pregnant women, adults with chronic illnesses (such as diabetes), and the elderly.

Tobacco use by any person in the household predisposes the entire household to food insecurity, both in the United States and globally.1 This “crowding out effect,” in which food income is used to purchase tobacco, is likely to impact households with a family member using illicit substances as well, although this area has been inadequately studied.8,9

The prevalence of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension are all higher in food insecure households than in low-income households that are not food insecure.3 Members of food insecure households that include chronically ill members often choose between paying for food and paying for health-care expenses. For example, two-thirds of food pantry clients in the United States report having to choose between buying food and medical care.10 These competing demands help explain the high rate of medication nonadherence observed in food insecure households.11,12,13

There are also factors that protect families against food insecurity even in the context of poverty. Although enrollment in federal nutrition programs such as SNAP is not adequate to pull many households out of food insecurity, they do reduce the depth and duration of food scarcity episodes. Financial skills (such as managing bills, making a budget, stretching groceries), knowledge of community resources for food assistance, and cooking skills also protect against food insecurity.14

STRUCTURAL FACTORS INFLUENCING FOOD INSECURITY

Policies that reduce the need for high expenditures in other parts of the budget allow households to avoid food insecurity. In the United States, for example, states with high food insecurity rates also have low average wages and high unemployment, high housing costs, low participation in federal nutrition programs, and a high tax burden on low-income households.15 Policy changes that relieve the budgets of poor households (e.g., access to affordable housing and health care, livable minimum wage) are likely to reduce food insecurity rates.

Besides these economic factors, ecological factors are also important drivers of food insecurity.6 For example, drought, flooding, and other natural disasters can have important consequences for food prices and regional food availability, particularly in the developing world. Political instability and social unrest can have an acute impact on food prices and food availability, and chronically undermine food availability by reducing investment in agriculture. Finally, the volatility of food prices affects the degree to which the poor, in particular, are able to access food.

FOOD INSECURITY AND ILLNESS