Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas

Key Points

The intraocular pressure is an important datum in the deliberation on when it is necessary to treat a patient with a carotid-cavernous fistula urgently, particularly when there are conflicting clinical concerns due to other injuries.

Intracranial venous drainage may be clinically silent, but is a significant concern for the development of intracranial venous hypertension.

Carotid-cavernous fistulas used to be among the most dramatic of angiographic diagnostic and interventional procedures, but since the advent of airbags in cars they have become a rarity, at least in the Occident. They are still common in countries where scooter transportation at high speed and without helmets is prevalent, and most acutely where such transportation comes to a sudden stop. A descriptive scheme for carotid-cavernous fistulas and dural arteriovenous malformations of the cavernous sinus that is frequently invoked is the Barrow classification (1). This describes the direct type of fistula, that is, a tear of the internal carotid artery as a Type A, and describes three categories, Types B to D, of indirect fistulas depending on arterial supply. Other than the fact that it discerns between direct and indirect fistulas, this classification scheme, particularly in its subcategorization of dural arteriovenous malformations according to this feature, is of little utility, and is mentioned here only because it is referred to frequently in papers and lectures. This chapter deals with direct fistulas with direct communication between the internal carotid artery and the paracavernous venous structures. Dural arteriovenous malformations and lesser fistulous lesions are discussed in Chapter 20.

Although the term “carotid-cavernous fistula” is often applied in the vernacular to dural arteriovenous malformations of the cavernous sinus, the two conditions are distinct with several implications for treatment. Carotid-cavernous fistula is the consequence of a transmural tear in the cavernous carotid artery establishing a fistula to the ipsilateral venous structures, usually the cavernous sinus. It is most commonly seen in young males following trauma, or in older females following spontaneous rupture of a pre-existent cavernous aneurysm (2). Occasional iatrogenic cases can be seen following transphenoidal surgery. Typically, onset is acute with a loud orbital bruit, proptosis, chemosis, eversion of the conjunctiva, corneal abrasions, and palsy of the VI or other cranial nerves. With rapid maturation of the fistulous rent in the arterial wall, the volume of flow and venous hypertensive complications can escalate quickly leading to secondary glaucoma, intracranial venous hypertension, venous infarcts, and cerebrovascular compromise due to steal (Fig. 23-1). For this reason, treatment can frequently be necessary on an emergency basis, posing a conflict in many patients with other aspects of treatment for traumatic injuries to viscera or intracranial structures (3,4,5).

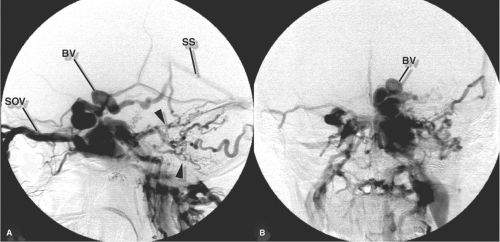

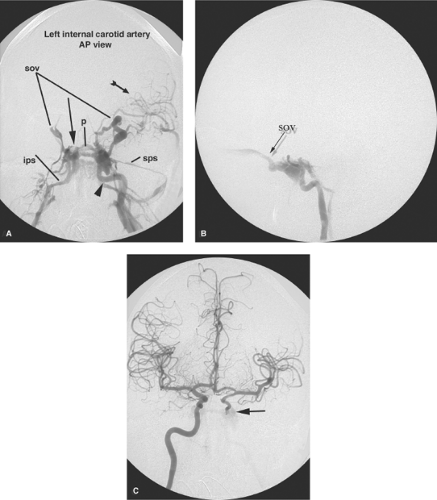

Angiographic diagnosis of carotid-cavernous fistulas is easy as the abnormality is usually fairly prominent (Figs. 23-2–23-6). What is not so straightforward is identifying precisely the location and extent of the arterial tear. This is because the volume of flow to the venous side engulfs the artery with venous contrast and obscures the view of the leakage point. Bumping up the frame rate per second for the DSA run can help enormously, but the most useful images are frequently those obtained of the fistula indirectly through the circle of Willis, particularly the vertebral artery. Reflux via the ipsilateral posterior communicating artery with retrograde flow to the fistula is often the best indicator of the upper edge of the tear, information that can be very useful in planning an endovascular treatment.

Secondly, information from the diagnostic angiogram relevant to the salvageability or otherwise of the carotid artery is important for evaluating the therapeutic options for a particular patient. Almost invariably, if there is reflux down the supraclinoidal carotid artery from the circle of Willis, the patient will have effectively undergone a successful test occlusion of the injured internal carotid artery, that is, the carotid artery can be sacrificed as a therapeutic option. However, occasional cases can be seen where continued intracranial flow past the fistula is necessary and in these patients the carotid artery has to be preserved.

Treatment of Carotid-Cavernous Fistulas

Some carotid-cavernous fistulas do not need to be treated immediately if, for instance, there are other more pressing problems in hand with a multitrauma patient with a low-flow lesion and clinical contraindications to heparinization during an endovascular procedure. A very tiny fistula may be of no immediate consequence and some undergo

spontaneous regression (Fig. 23-7). Imaging and clinical features of carotid-cavernous fistulas that indicate a need for urgent treatment include evidence of venous hypertension affecting the intracranial venous system, increasing proptosis or diminishing visual acuity, increasing intraocular pressure, elevated intracranial pressure, rupture into the subarachnoid space, and extension of a pseudoaneurysm or venous varix from the cavernous sinus into the subarachnoid space (5).

spontaneous regression (Fig. 23-7). Imaging and clinical features of carotid-cavernous fistulas that indicate a need for urgent treatment include evidence of venous hypertension affecting the intracranial venous system, increasing proptosis or diminishing visual acuity, increasing intraocular pressure, elevated intracranial pressure, rupture into the subarachnoid space, and extension of a pseudoaneurysm or venous varix from the cavernous sinus into the subarachnoid space (5).

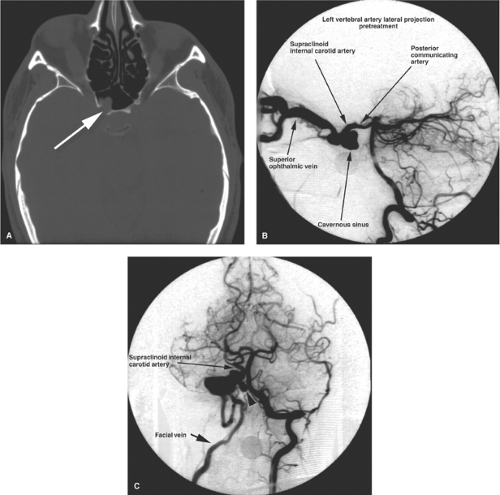

Figure 23-4. (A–C) Posttraumatic carotid-cavernous fistula with ipsilateral carotid dissection. A young adult male presented with history of mild right-sided proptosis and a pulsatile bruit following an assault with a lead pipe. A CT examination demonstrated prominent vascular structures in the region of the right cavernous sinus. A most significant finding on the bone windows was a breach (arrow in A) in the bony wall of the sphenoid sinus with protrusion of a soft tissue density from the cavernous sinus. With a history of trauma and a diagnosis of carotid-cavernous fistula, the possibility of a pseudoaneurysm or tense venous pouch expanding into the sphenoid sinus must be considered, raising the risk of life-threatening epistaxis from that site. The right common carotid artery arteriogram (not shown) demonstrated complete occlusion of the right internal carotid artery. The carotid-cavernous fistula filled via the right posterior communicating artery from the left vertebral artery injection (B). Contrast flows from the right posterior cerebral artery to the supraclinoidal internal carotid artery. A distended cavernous sinus drains exclusively to a massively distended superior ophthalmic vein. Despite the torrential rate of flow in the superior ophthalmic vein, the patient’s proptosis was mild. This was because of prompt drainage to the facial vein, seen on the Townes view (C). On this view, a medially projecting pouch (arrowhead in C) from the genu of the internal carotid artery is seen, correlating with the CT appearance in (A). Because of the possibility of massive epistaxis from the pouch or pseudoaneurysm, urgent embolization was undertaken.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|