Cerebral hemisphere and cerebral cortex

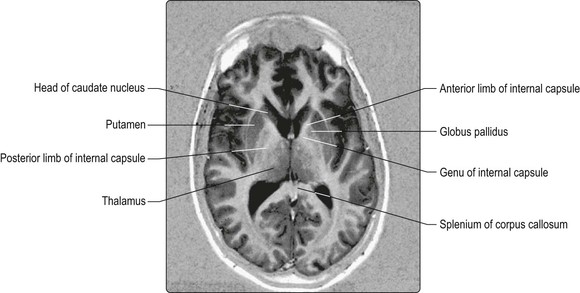

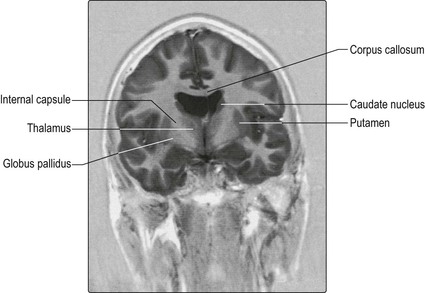

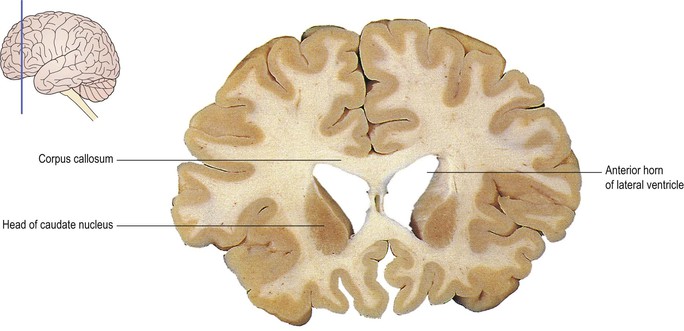

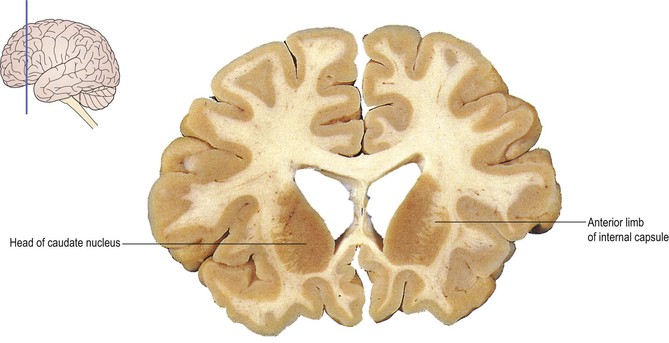

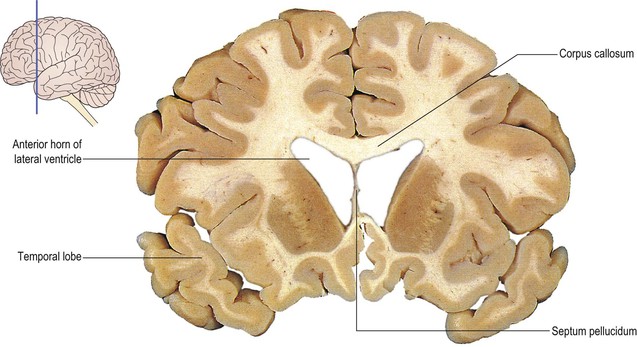

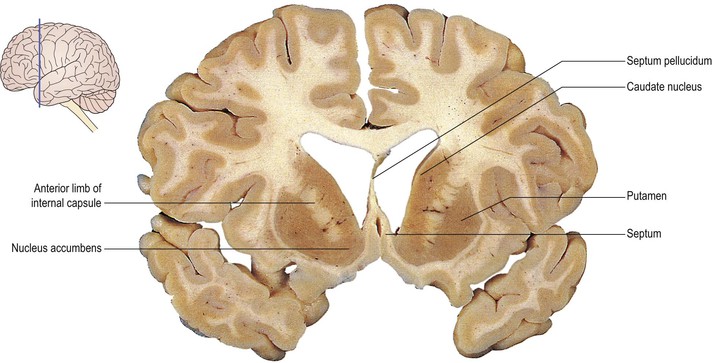

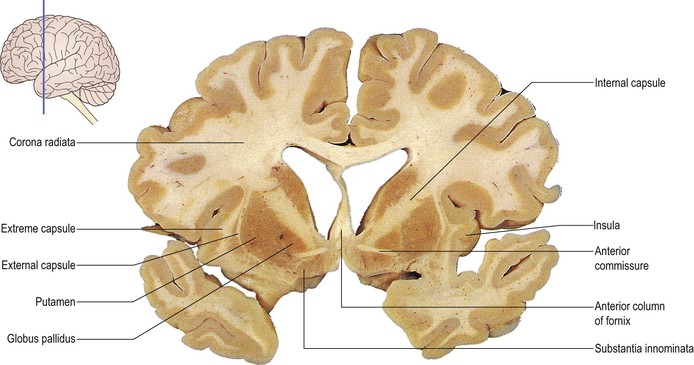

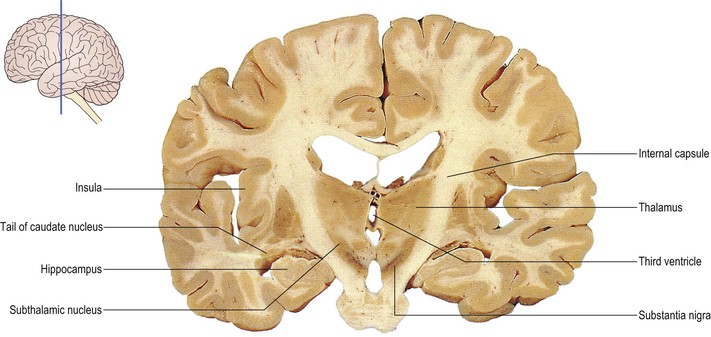

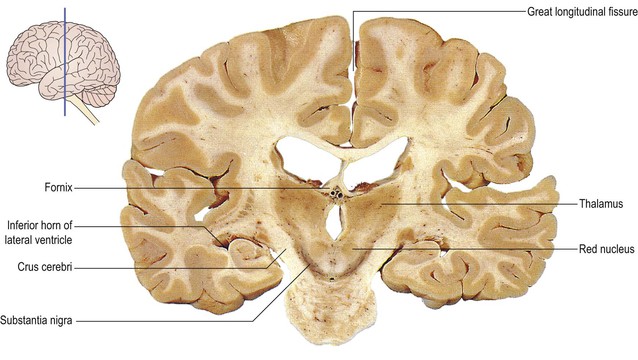

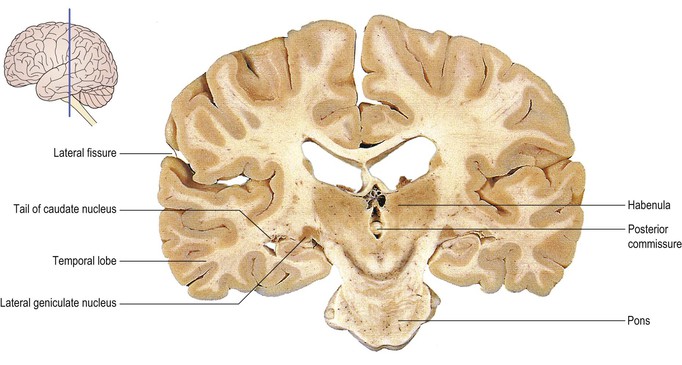

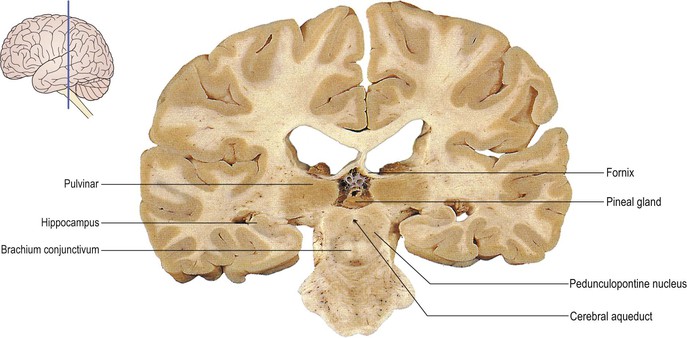

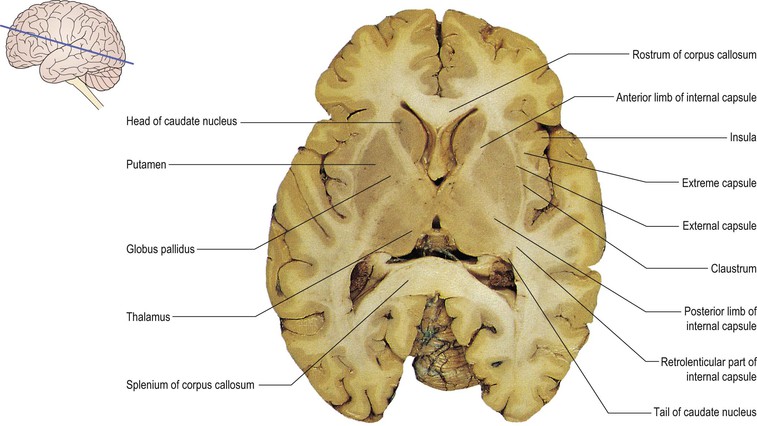

The cerebral hemisphere is derived from the embryological telencephalon (Ch. 1). It is the largest part of the forebrain and it reaches the greatest degree of development in the human brain. Superficially, the cerebral hemisphere consists of a layer of grey matter, the cerebral cortex, which is highly convoluted to form a complex pattern of ridges (gyri; singular, gyrus) and furrows (sulci; singular, sulcus). This serves to maximise the surface area of the cerebral cortex, about 70% of which is hidden within the depths of sulci (Figs 13.1, 13.2). Beneath the surface, axons running to and from the cells of the cortex form an extensive mass of white matter. Figures 13.3–13.12 show successive coronal sections through the brain. The vast majority of those nerve fibres that pass between the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures are condensed, deep within the hemisphere, into a broad sheet called the internal capsule (Figs 13.4–13.11; see also Fig. 1.27). Between the internal capsule and the cortical surface, fibres radiate in and out to produce a fan-like arrangement, the corona radiata. Buried within the white matter lie a number of nuclear masses. Most notable among these are the caudate nucleus, putamen and globus pallidus, known collectively as ‘the basal ganglia’ or ‘corpus striatum’ (Figs 13.3–13.15). Within the cerebral hemisphere lies the large C-shaped cavity of the lateral ventricle, which is considered with the rest of the ventricular system in Chapter 6.

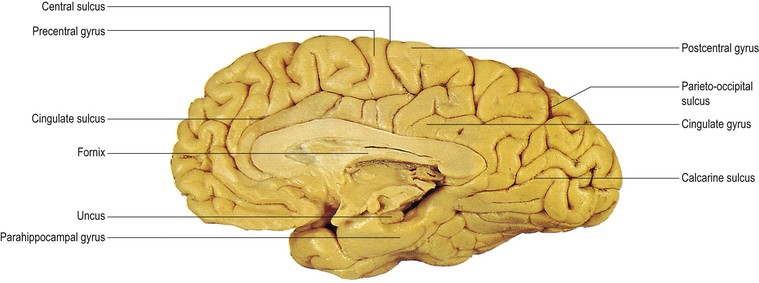

The two cerebral hemispheres are separated by a deep cleft, the great longitudinal fissure, which accommodates the meningeal falx cerebri. In the depths of the fissure, the hemispheres are united by the corpus callosum, an enormous sheet of commissural nerve fibres which run between corresponding areas of the two cortices (Figs 13.2–13.15; see also Figs 13.22, 13.23, 13.24).

Gyri, sulci and lobes of the cerebral hemisphere

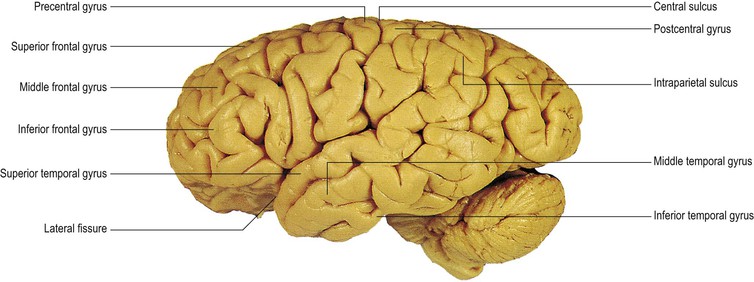

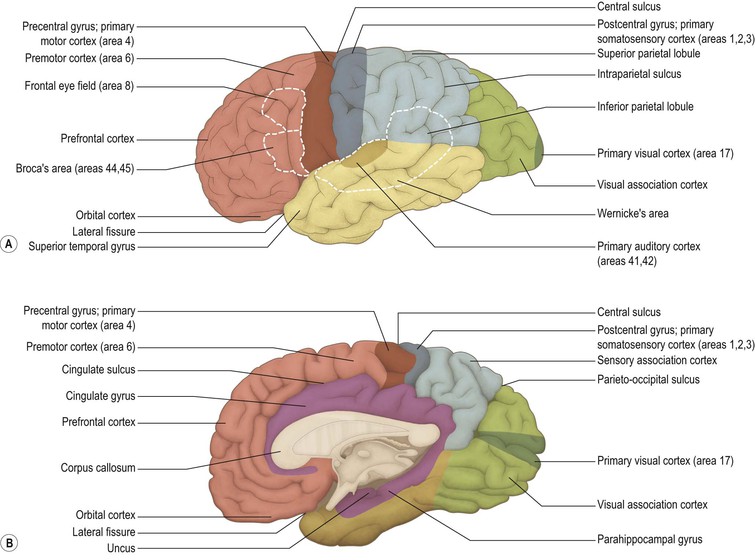

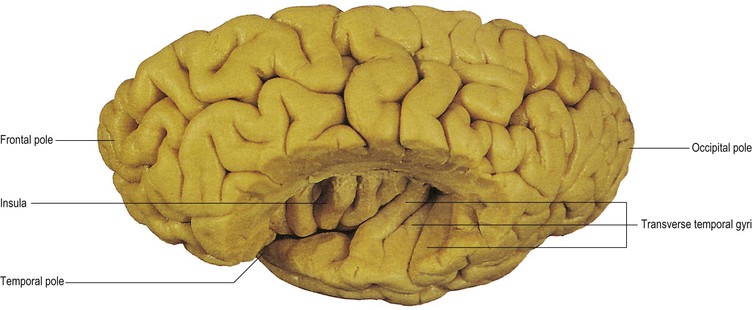

Certain gyri and sulci on the surface of the hemisphere are consistently located in different individuals and form the basis of dividing the hemisphere into four lobes, namely the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes. Their principal topographical features and functional significance are described below. The most conspicuous and deepest cleft on the lateral surface of the hemisphere is the lateral fissure (Fig. 13.1). This separates the temporal lobe below from the frontal and parietal lobes above. Within the depths of the lateral fissure lies a cortical area known as the insula (Figs 13.6–13.14). The parts of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes that overlie the insula are called the opercula. Also on the lateral surface of the hemisphere, a single, uninterrupted sulcus can usually be identified, running continuously between the great longitudinal fissure and the lateral fissure. This is the central sulcus, which marks the boundary between the frontal and parietal lobes (Figs 13.1, 13.16). The central sulcus extends for a short distance onto the medial surface of the hemisphere, within the great longitudinal fissure (Figs 13.2, 13.16).

The frontal lobe constitutes the entire region in front of the central sulcus. Immediately in front of the sulcus, and running parallel to it, lies the precentral gyrus, which is the primary motor region of the cerebral cortex. In front of the precentral gyrus, the rest of the frontal lobe consists of a more variable pattern of convolutions, of which the superior, middle and inferior frontal gyri can usually be identified (Fig. 13.1).

Behind the central sulcus, and above the lateral fissure, lies the parietal lobe. Its most anterior part is the postcentral gyrus, which is the site of the primary somatosensory cortex. Behind the postcentral gyrus, on the lateral surface of the hemisphere, the intraparietal sulcus divides the rest of the parietal lobe into superior and inferior parietal lobules (Figs 13.1, 13.16).

The boundary between the parietal lobe and the posteriorly located occipital lobe is not coincident with a single sulcus on the lateral surface of the hemisphere; however, it is clearly marked by the deep parieto-occipital sulcus on the medial surface (Figs 13.2, 13.16). The occipital lobe does not bear any important landmarks on its lateral surface but, on the medial surface, the prominent calcarine sulcus indicates the location of the primary visual cortex (Figs 13.2, 13.16).

The temporal lobe lies beneath the lateral fissure, merging posteriorly with the parietal and occipital lobes. On its lateral surface, the temporal lobe is divided into three principal gyri that run roughly parallel to the lateral fissure: the superior, middle and inferior temporal gyri (Fig. 13.1). The superior temporal gyrus includes the primary auditory cortex. Most of this functional region is situated on the superior bank of the gyrus, within the lateral fissure, where the transverse temporal gyri, or Heschl’s convolutions, provide a more precise localisation (Fig. 13.17).

On the medial surface of the hemisphere, certain portions of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes also constitute components of the limbic system. Curving around the corpus callosum, and running parallel to it, lies the cingulate gyrus (Figs 13.2, 13.16), separated from the rest of the hemisphere by the cingulate sulcus. The cingulate gyrus passes posteriorly and inferiorly round the posterior portion, or splenium, of the corpus callosum to become continuous with the parahippocampal gyrus of the temporal lobe. Deep to the parahippocampal gyrus, within the temporal lobe, lies the hippocampus (Figs 13.8–13.12). This structure is formed by an in-curling of the inferomedial part of the temporal lobe. The cingulate gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus are sometimes referred to as the limbic lobe of the cerebral hemisphere.