Cerebral Hemispheres/Telencephalon: Introduction

The cerebral hemispheres make us human. They include the cerebral cortex (which consists of six lobes on each side: frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, insular, and limbic), the underlying cerebral white matter, and a complex of deep gray matter masses, the basal ganglia. From a phylogenetic point of view, the cerebral hemispheres, particularly the cortex, are relatively new. Folding of the cortex, in gyri separated by sulci, permits a highly expanded cortical mantle to fit within the skull vault in higher mammals, including humans. The cortex is particularly well developed in humans. There are multiple maps (motor, somatosensory, visual) of the body and the external world within the cortex. The cortex is highly parcellated, with different parts of the cortex being responsible for a variety of higher brain functions, including manual dexterity (the “opposing thumb” and the ability, eg, to move the fingers individually so as to play the piano); conscious, discriminative aspects of sensation; and cognitive activity, including language, reasoning, planning, and many aspects of learning and memory.

Development

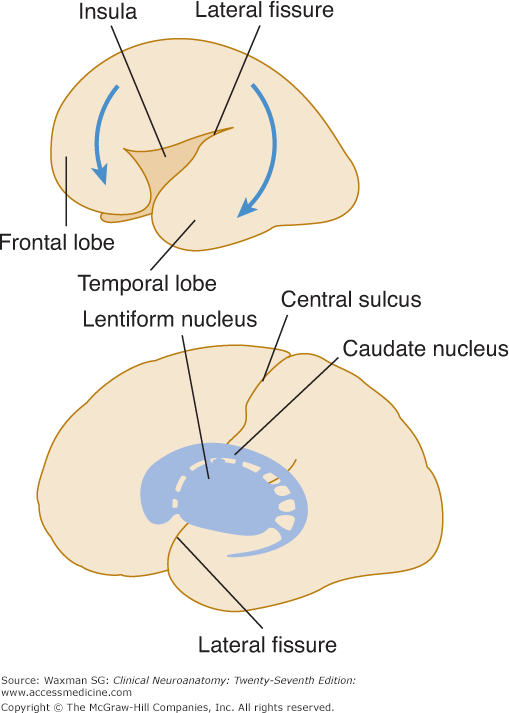

The telencephalon (endbrain) gives rise to the left and right cerebral hemispheres (Fig 10–1). The hemispheres undergo a pattern of extensive differential growth; in the later stages, they resemble an arch over the lateral fissure (Fig 10–2).

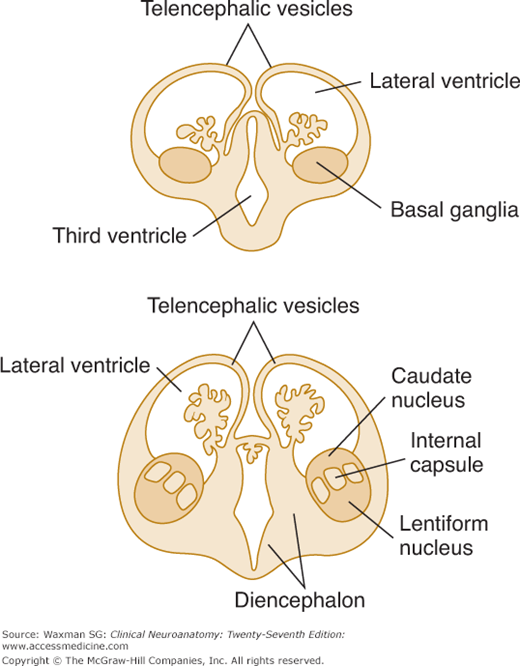

The basal ganglia arise from the base of the primitive telencephalic vesicles (Fig 10–3). The growing hemispheres gradually cover most of the diencephalon and the upper part of the brain stem. Fiber connections (commissures) between the hemispheres are formed first at the rostral portions as the anterior commissure, later extending posteriorly as the corpus callosum (Fig 10–4).

Anatomy of the Cerebral Hemispheres

The cerebral hemispheres make up the largest portion of the human brain. The cerebral hemispheres appear as highly convoluted masses of gray matter that are organized into two somewhat symmetrical (but not totally symmetrical) folded structures. The crests of the cortical folds (gyri) are separated by furrows (sulci) or deeper fissures. The folding of the cortex into gyri and sulci permits the cranial vault to contain a large area of cortex (nearly 2½ square feet if the cortex were unfolded), more than 50% of which is hidden within the sulci and fissures. The presence of gyri and sulci, in a pattern that is relatively constant from brain to brain, makes it easy to identify cortical areas that fulfill specific functions.

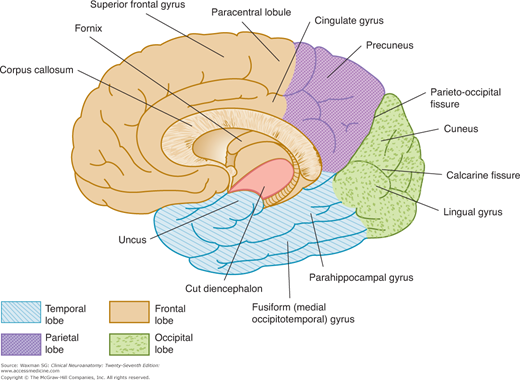

The surfaces of the cerebral hemispheres contain many fissures and sulci that separate the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes from each other and the insula (Figs 10–5 and 10–6). Some gyri are relatively invariant in location and contour, whereas others show variation. The overall plan of the cortex as viewed externally, however, is relatively constant from person to person.

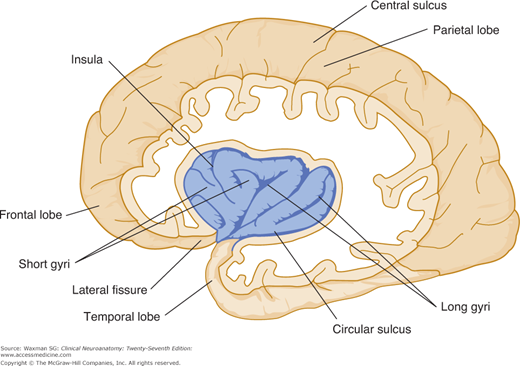

The lateral cerebral fissure (Sylvian fissure) separates the temporal lobe from the frontal and parietal lobes. The insula, a portion of cortex that did not grow much during development, lies deep within the fissure (Fig 10–7). The circular sulcus (circuminsular fissure) surrounds the insula and separates it from the adjacent frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes.

The hemispheres are separated by a deep median fissure, the longitudinal cerebral fissure. The central sulcus (the fissure of Rolando) arises about the middle of the hemisphere, beginning near the longitudinal cerebral fissure and extending downward and forward to about 2.5 cm above the lateral cerebral fissure (see Fig 10–5). The central sulcus separates the frontal lobe from the parietal lobe. The parieto-occipital fissure passes along the medial surface of the posterior portion of the cerebral hemisphere and then runs downward and forward as a deep cleft (see Fig 10–6). The fissure separates the parietal lobe from the occipital lobe. The calcarine fissure begins on the medial surface of the hemisphere near the occipital pole and extends forward to an area slightly below the splenium of the corpus callosum (see Fig 10–6).

The corpus callosum is a large bundle of myelinated and nonmyelinated fibers, the great white commissure that crosses the longitudinal cerebral fissure and interconnects the hemispheres (see Figs 10–4 and 10–6). The body of the corpus callosum is arched; its anterior curved portion, the genu, continues anteroventrally as the rostrum. The thick posterior portion terminates in the curved splenium, which lies over the midbrain.

The corpus callosum serves to integrate the activity of the two hemispheres and permits them to communicate with each other. Most parts of the cerebral cortex are connected with their counterparts in the opposite hemisphere by axons that run in the corpus callosum. The corpus callosum is the largest of the interhemispheric commissures and is largely responsible for coordinating the activities of the two cerebral hemispheres.

The frontal lobe includes not only the motor cortex but also frontal association areas responsible for initiative, judgment, abstract reasoning, creativity, and socially appropriate behavior (inhibition of socially inappropriate behavior). These latter parts of the cortex are the phylogenetically newest and the most uniquely “human”. The frontal lobe extends from the frontal pole to the central sulcus and the lateral fissure (see Figs 10–5 and 10–6).

The precentral sulcus lies anterior to the precentral gyrus and parallel to the central sulcus. The superior and inferior frontal sulci extend forward and downward from the precentral sulcus, dividing the lateral surface of the frontal lobe into three parallel gyri: the superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri. The inferior frontal gyrus is divided into three parts: the orbital part lies rostral to the anterior horizontal ramus; the triangular, wedge-shaped portion lies between the anterior horizontal and anterior ascending rami; and the opercular part is between the ascending ramus and precentral sulcus.

The orbital sulci and gyri are irregular in contour. The olfactory sulcus lies beneath the olfactory tract on the orbital surface; lying medial to it is the straight gyrus (gyrus rectus). The cingulate gyrus is the crescent-shaped, or arched, convolution on the medial surface between the cingulate sulcus and the corpus callosum. The paracentral lobule is on the medial surface of the hemisphere and is the continuation of the precentral and postcentral gyri.

The prefrontal cortex includes higher order association cortex involved in judgment, reasoning, initiative, higher order social behavior, and similar functions. The prefrontal cortex is located anterior to the primary motor cortex within the precentral gyrus and the adjacent premotor cortex.

The parietal lobe extends from the central sulcus to the parieto-occipital fissure; laterally, it extends to the level of the lateral cerebral fissure (see Figs 10–5 and 10–6). The postcentral sulcus lies behind the postcentral gyrus. The intraparietal sulcus is a horizontal groove that sometimes unites with the postcentral sulcus. The superior parietal lobule lies above the horizontal portion of the intraparietal sulcus and the inferior parietal lobule lies below it.

The supramarginal gyrus is the portion of the inferior parietal lobule that arches above the ascending end of the posterior ramus of the lateral cerebral fissure. The angular gyrus arches above the end of the superior temporal sulcus and becomes continuous with the middle temporal gyrus. The precuneus is the posterior portion of the medial surface between the parieto-occipital fissure and the ascending end of the cingulate sulcus.

The occipital lobe—which most notably houses the primary visual cortex—is situated behind the parieto-occipital fissure (see Figs 10–5 and 10–6). The calcarine fissure divides the medial surface of the occipital lobe into the cuneus and the lingual gyrus. The cortex on the banks of the calcarine fissure (termed the striate cortex because it contains a light band of myelinated fibers in layer IV) is the site of termination of visual afferents from the lateral geniculate body; this region of cortex thus functions as the primary visual cortex. The wedge-shaped cuneus lies between the calcarine and parieto-occipital fissures, and the lingual (lateral occipitotemporal) gyrus is between the calcarine fissure and the posterior part of the collateral fissure. The posterior part of the fusiform (medial occipitotemporal) gyrus is on the basal surface of the occipital lobe.

The temporal lobe lies below the lateral cerebral fissure and extends back to the level of the parieto-occipital fissure on the medial surface of the hemisphere (see Figs 10–5 and 10–6). The lateral surface of the temporal lobe is divided into the parallel superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri, which are separated by the superior and middle temporal sulci. The inferior temporal sulcus extends along the lower surface of the temporal lobe from the temporal pole to the occipital lobe. The transverse temporal gyrus occupies the posterior part of the superior temporal surface. The fusiform gyrus is medial and the inferior temporal gyrus lateral to the inferior temporal sulcus on the basal aspect of the temporal lobe. The hippocampal fissure extends along the inferomedian aspect of the lobe from the area of the splenium of the corpus callosum to the uncus. The parahippocampal gyrus lies between the hippocampal fissure and the anterior part of the collateral fissure. Its anterior part, the most medial portion of the temporal lobe, curves in the form of a hook; it is known as the uncus.

The insula is a sunken portion of the cerebral cortex (see Fig 10–7). It lies at the bottom of a deep fold within the lateral cerebral fissure and can be exposed by separating the upper and lower lips (opercula) of the lateral fissure.

The cortical components of the limbic system include the cingulate, parahippocampal, and subcallosal gyri as well as the hippocampal formation. These components form a ring of cortex, much of which is phylogenetically old with a relatively primitive microscopic structure, which becomes a border (limbus) between the diencephalon and more lateral neocortex of the cerebral hemispheres. The anatomy and function of these components are discussed in Chapter 19.

Several poorly defined cell islands, located beneath the basal ganglia deep in the hemisphere, project widely to the cortex. These cell islands include the basal forebrain nuclei (also known as the nuclei of Meynert or substantia innominata), which send widespread cholinergic projections throughout the cerebral cortex. Located just laterally are the septal nuclei, which receive afferent fibers from the hippocampal formation and reticular system and send axons to the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and midbrain.

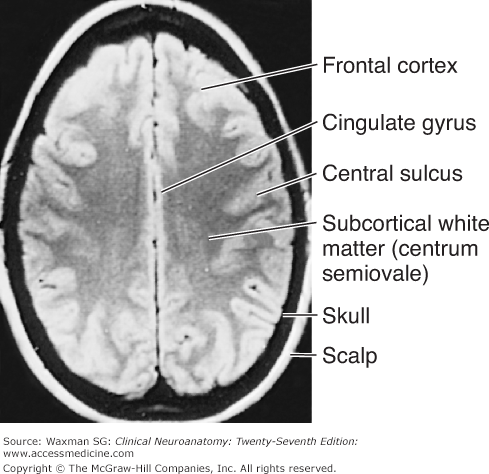

The white matter of the adult cerebral hemisphere contains myelinated nerve fibers of many sizes as well as neuroglia (mostly oligodendrocytes) (Fig 10–8). The white center of the cerebral hemisphere, sometimes called the centrum semiovale, contains myelinated transverse fibers, projection fibers, and association fibers.

Transverse fibers interconnect the two cerebral hemispheres. Many of these transverse fibers travel in the corpus callosum that comprises the largest bundle of fibers; most of these arise from parts of the neocortex of one cerebral hemisphere and terminate in the corresponding parts of the opposite cerebral hemisphere. The anterior commissure connects the two olfactory bulbs and temporal lobe structures. The hippocampal commissure, or commissure of the fornix, joins the two hippocampi; it is variable in size (see Chapter 19).

These fibers connect the cerebral cortex with lower portions of the brain or the spinal cord. The corticopetal (afferent) fibers include the geniculocalcarine radiation from the lateral geniculate body to the calcarine cortex, the auditory radiation from the medial geniculate body to the auditory cortex, and thalamic radiations from the thalamic nuclei to specific cerebrocortical areas. Afferent fibers tend to terminate in the more superficial cortical layers (layers I to IV; see the next section), with thalamocortical afferents (especially the specific thalamocortical afferents that arise in the ventral tier of the thalamus, lateral geniculate, and medial geniculate) terminating in layer IV.

Corticofugal (efferent) fibers proceed from the cerebral cortex to the thalamus, brain stem, or spinal cord. Projection efferents to the spinal cord and brain stem play major roles in the transmission of motor commands to lower motor neurons, and tend to arise from large pyramidal neurons in deeper cortical layers (layer V).

These fibers connect the various portions of a cerebral hemisphere and permit the cortex to function as a coordinated whole. The association fibers tend to arise from small pyramidal cells in cortical layers II and III (Fig 10–9).

Short association fibers, or U fibers, connect adjacent gyri; those located in the deeper portions of the white matter are the intracortical fibers, and those just beneath the cortex are called subcortical fibers.

Long association fibers connect more widely separated areas. The uncinate fasciculus crosses the bottom of the lateral cerebral fissure and connects the inferior frontal lobe gyri with the anterior temporal lobe. The cingulum, a white band within the cingulate gyrus, connects the anterior perforated substance and the parahippocampal gyrus. The arcuate fasciculus sweeps around the insula and connects the superior and middle frontal convolutions (which contain the speech motor area) with the temporal lobe (which contains the speech comprehension area). The superior longitudinal fasciculus connects portions of the frontal lobe with occipital and temporal areas. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus, which extends parallel to the lateral border of the inferior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricle, connects the temporal and occipital lobes. The occipitofrontal fasciculus extends backward from the frontal lobe, radiating into the temporal and occipital lobes.

Microscopic Structure of the Cortex

The cerebral cortex contains three main types of neurons arranged in a layered structure: pyramidal cells (shaped like a tepee, with an apical dendrite reaching from the upper end toward the cortical surface, and basilar dendrites extending horizontally from the cell body); stellate neurons (star shaped, with dendrites extending in all directions); and fusiform neurons (found in deeper layers, with a large dendrite that ascends toward the surface of the cortex). The axons of pyramidal and fusiform neurons form the projection and association fibers, with large layer V pyramidal neurons projecting their axons to the spinal cord and brain stem, smaller layer II and layer III pyramidal cells sending association axons to other cortical areas, and fusiform neurons giving rise to corticothalamic projections. Stellate neurons are interneurons whose axons remain within the cortex.