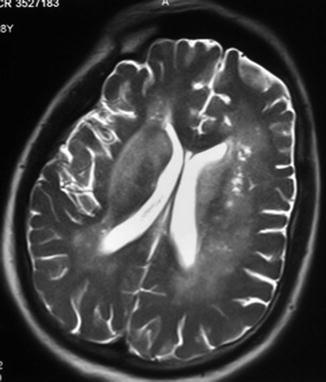

Fig. 9.1

Contrast-enhanced axial T2-weighted cranial MRI of a male patient with meningoencephalitis. Note the presence of fresh infarction of the left thalamus (arrowhead) (From Jochum et al. [20] with permission)

Clinical clues suggesting headache, nuchal rigidity, and cranial nerve palsies may be present due to meningitic process. Stroke as a presenting manifestation of neurobrucellosis is uncommon in which case the diagnosis may not be suspected [6]. TIAs are also a common manifestation; in one series two out of four patients who developed TIA had no prior history of brucellosis [9]. McLean et al. [26] described a total of 18 patients with neurobrucellosis, of which four patients had a stroke: two ischemic strokes and two ICH presumably due to mycotic aneurysm. Nevertheless, neither angiogram nor autopsy was performed. Al Deeb et al. [4] in their series of 13 patients with neurobrucellosis reported a single patient with ischemic stroke who had hypodensities in CT scan with a normal DSA. Pascual et al. [28] reported two patients with vascular involvement as TIA or SAH, and both patients had normal angiograms. Vogt et al. [32] described a patient with neurobrucellosis and multiple subcortical infarcts, but angiogram was not done. Hernandez et al. [17] have reported neurobrucellosis patients with stroke. Recently, Adaletli et al. [1] have reported a patient with stroke and an angiogram showing evidence of vasculopathy like occlusion of branches of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA), vascular cutoff signs, vascular contour irregularities, and stenosis. Gul et al. [14], in their pooled analysis of 187 cases, reported six cases (3.2 %), one case each of SAH and subdural hematoma and four cases of ischemic stroke. Jochum et al. [20] have reported a case of neurobrucellosis who had a thalamic infarct as a complication, but no angiography was done on this patient.

In 2006, Bingöl et al. [9] have described four cases of neurobrucellosis presenting as TIAs. Inan et al. [18] have reported TIA and stroke as the presenting feature in neurobrucellosis. Akhondian et al. [3] have described an 11-year-old child with neurobrucellosis who had TIA as the presenting manifestation, but angiogram was not done on this patient.

In a large series of patients with neurobrucellosis, headache, fever, weight loss, sweating, and back pain were the most common presenting symptoms [14]. Meningeal irritation, hypesthesia, confusion, and hepatosplenomegaly were the most commonly encountered physical signs. Presence of systemic features such as arthralgia, fever, meningeal irritation, peripheral nervous system involvement, and cranial neuropathies or hearing loss in young patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of cerebrovascular accident in endemic regions should trigger a high degree of suspicion for neurobrucellosis.

Brucella-related cerebral aneurysms may present with SAH or maybe detected incidentally on neuroimaging. Aneurysms involving the BA, anterior cerebral artery, and MCA have been reported [5, 19, 21, 25]. In patients presenting with SAH, history of fever and other systemic complaints prompts consideration of a mycotic aneurysm due to an infective etiology. McLean et al. [26] described two patients with ICH due to a presumed mycotic aneurysm. Of the eight reported cases, three involved the BA which is an uncommon site for mycotic aneurysms, and these have been postulated to be due to basilar meningitis [26].

Patients with hemorrhagic infarcts secondary to CVT may present with seizures [13]. Other rare presentations thought to be due to cerebral venous sinus involvement are headache, papilledema, and raised intracranial pressure, without any focal deficits, mimicking pseudotumor cerebri [27]. Since most descriptions of cerebrovascular brucellosis are restricted to small case series or case reports, manifestations cannot be categorized as being typical and may vary.

9.4 Differential Diagnosis

Neurological involvement in brucellosis is rare, especially as a presenting feature; the differential diagnosis includes other infectious, neoplastic, and inflammatory conditions which can have a similar presentation. As mentioned above, the cerebrovascular manifestations in neurobrucellosis are attributable to multiple mechanisms including mycotic aneurysms, infective emboli from the heart, vasculitis, and even adjacent inflammation of the cerebral sinuses, from the meninges causing CVT. In any young patient with a stroke with features of chronic meningitis or arachnoiditis, from an endemic region, neurobrucellosis should be considered. In tropical countries like India, a high index of suspicion of neurobrucellosis is mandatory in those patients with a history of traveling to the Middle east/Gulf countries and in those who consume raw milk, but a patient presenting with pure cerebrovascular manifestations should be subjected to the standard evaluation for a young stroke. Concurrent systemic features and evidence of meningitis clinically or by CSF analysis should arouse suspicion. The common differential diagnoses which would be considered are neurotuberculosis, demyelination, primary CNS lymphoma, vasculitis, and neurosyphilis.

9.4.1 Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can present in a very similar manner and may be difficult to distinguish since endemic regions of both these infections overlap significantly. Erdem et al. [11] have shown that Thwaites or Lancet scoring systems used for tubercular meningitis may lead to a misdiagnosis of neurobrucellosis as tubercular meningitis in endemic countries. In fact, many patients with neurobrucellosis may be treated as misdiagnosis of tuberculosis, and neurobrucellosis is suspected only when the patient worsens in spite an adequate antitubercular treatment [22]. The CSF picture composed of raised protein value, low sugar and lymphocytic pleocytosis, as well as stroke and cranial nerve palsies represents a close overlap of both these chronic infections. A brucellosis serology would be valuable in this situation to confirm the diagnosis.

9.4.2 Demyelination

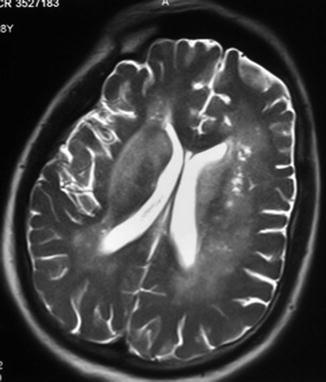

Neurobrucellosis with stroke-like presentations may mimic a demyelinating disease on neuroimaging. The involvement of the deep gray matter is unusual and may resemble closely an acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (Fig. 9.2) [29]. Nevertheless, the presentation with systemic features would be suggestive of a secondary cause of demyelination.

Fig. 9.2

Axial T2-weighted cranial MRI showing bilateral periventricular and basal ganglia hyperintensities

9.4.3 Lymphoma

Lymphoma can present with chronic meningitis and demyelination-like lesions, while intravascular lymphoma can even have stroke-like episodes.

9.4.4 Neurosyphilis

Even in this era, neurosyphilis cannot be forgotten as it is the great mimicker, and its neurovascular complications may closely mimic neurobrucellosis.

9.5 Investigations

9.5.1 CSF Examination

The evaluation of a suspected case of neurobrucellosis is usually tailored to the presenting clinical features. CSF examination shows an elevated protein, reduced glucose concentration, and moderate leukocytosis with predominant lymphocytes [26]. The rate of isolation of Brucella spp. from CSF is low (<20 %); hence, the diagnosis of neurobrucellosis depends on the specific antibodies in the CSF [24]. Even though the positive culture is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis, low yield and longtime consumed makes it less practical as a viable option for diagnosis in clinical practice.

9.5.2 Neurophysiologic Evaluation

9.5.3 Neuroimaging

Cranial CT scan and MRI should be done to identify and localize the lesion. Angiography (CT angiography and full four-vessel angiography if required in cases of suspected mycotic aneurysms) and echocardiography to identify brucellar endocarditis will add to the evidence for vascular involvement of neurobrucellosis. CT venography or MR venography in CVT is diagnostic.

9.6 Management

The management protocol for brucellosis has been discussed elsewhere (Chaps. 20 and 21). We have restricted our discussion to specific management principals of cerebrovascular complications of neurobrucellosis.

9.6.1 Mycotic Aneurysm

There have been eight reported cases of mycotic aneurysms related to neurobrucellosis. Hansmann et al. [16] described the first case with an autopsy finding of mycotic aneurysm due to neurobrucellosis. Jabbour et al. [19] described a proximally located BA aneurysm which disappeared following successful medical therapy. SAH with normal angiogram has been described in one patient [28]. Kaya et al. [21] reported a thrombosed distal dissecting aneurysm of the BA which resolved with medical management. Mycotic aneurysm with neurobrucellosis has been treated surgically after failed medical management [5, 12]. Ranjbar et al. [30] have described 20 patients with neurobrucellosis, among which one patient had a stroke due to a mycotic aneurysm rupture. There was no mention of angiogram in this patient. Thus, of the eight cases, only two cases of aneurysm warranted invasive management. Amiri et al. [5] used surgical option, endovascular or surgical excision, only after an inadequate response to medical management. They opined that the factors determining the choice between endovascular and surgical excisions were morphology and location of the aneurysm, possibility of sacrificing the parent artery, status of valve replacement surgery, vasospasm, the severity and location of ICH, and general medical condition of the patient [5]. There is currently insufficient evidence to make recommendations for the management of mycotic aneurysm due to brucellosis. The practical approach would be to adopt an invasive line of management when there is no or inadequate response to conservative medical management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree