21 | Cerivcal Fractures in Ankylosing Spondylitis |

| Case Presentation |

History and Physical Examination

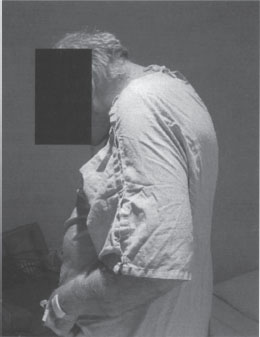

A 61-year-old man with a history of ankylosing spondylitis presented to the senior author (KDR) after sustaining a minor trauma to his cervical spine. The patient complained of extreme dysphagia, such that he could not even swallow water (Fig. 21–1). History and physical examination revealed that he had signs and symptoms consistent with myeloradiculopathy.

Figure 21–1 Preoperative patient photograph. Note the severe cervicothoracic kyphotic deformity.

Radiological Findings

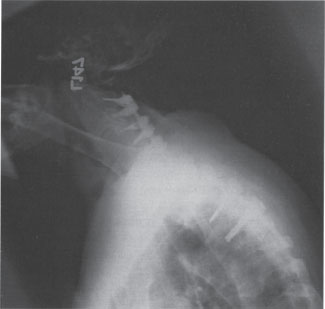

Radiographic evaluation revealed a compression fracture at the C7 level (Figs. 21–2, 21–3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also demonstrated central spinal canal stenosis at the C3-4 level, one of the few levels in the sub-axial spine where he was not ankylosed.

Diagnosis

Ankylosing spondylitis with C7 compression fracture and C3-4 stenosis

Figure 21–2 Lateral cervical radiograph of a 61 -year-old man with a history of ankylosing spondylitis who presented following minor trauma to his cervical spine. He complained of severe dysphagia and displayed signs and symptoms of myeloradiculopathy. Lateral radiograph demonstrates severe cervicothoracic kyphosis and a compression deformity at the C7 level.

Figure 21–3 Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating severe kyphotic deformity and a compression fracture at the C7 level. Also noted is preexisting severe central spinal canal stenosis at the C3-4 level.

| Background |

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory rheumatologic disease that can have severe manifestations in the cervical spine. The B27 allele on the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci is present in approximately 90% of those people with AS, compared with only 8% percent of American Caucasians. Only 10 to 20% of those individuals with the B27 allele will develop some form of spondyloarthropathy. The prevalence of AS within a given ethnic group has been shown to be proportional to the prevalence of the B27 antigen in that population. AS has been reported in men more than twice as frequently as in women, although it may be underreported in women due to a milder and slower disease progression.1 The presence of the B27 antigen does not confirm the diagnosis of AS. The diagnosis of this seronegative spondyloarthropathy is based on clinical and radiographic criteria. In contrast to the other seronegative spondyloarthropathies, spinal and sacroiliac ankylosis usually manifests by the third decade of life in patients with AS. This ankylosis and osteopenia of the spine creates a pathological condition that predisposes these patients to spinal kyphosis and fracture.

Patients with AS are predisposed to cervical spine fracture because of the increased stiffness and decreased bone density of the spine. Fused vertebral segments lack ligamentous and diskal energy-absorbing capability, and the thinned bone has a lower resistance to failure. Applied moments have longer lever arms to act on the fused segments, and therefore, low-energy trauma may lead to fracture in this scenario. The prevalence of cervical spine fracture has been shown to be greater in patients with AS than in the general population and often occurs in the sixth to eighth decades of life.2 A high index of suspicion must be maintained in patients with AS because significant injury can be sustained from only minimal trauma. Preexisting internal spine instrumentation may also predispose the ankylosed spine to multiple fractures, even following a minor traumatic event.3 Delay in diagnosis of cervical fractures is common in patients with AS. These patients are often used to living with some level of chronic neck pain, and an increase in their pain after trivial trauma will often not prompt them to seek medical treatment until neurological symptoms occur. An inability to see the ground ahead while walking due to extreme flexion deformity of the cervical spine has been shown to contribute to the frequency of injury in these patients.

Aggressive use of cervical imaging is required for patients who report increased neck pain, even without a history of significant trauma. Interpretation of plain radiographs is often complicated due to osteopenia, and visualization of the lower cervical spine is frequently hindered by the presence of kyphotic deformity. Tomography and computed tomographic (CT) evaluation with sagittal and coronal reconstructions can aid in identifying a fracture in the transverse plane.4 Triple phase bone scan or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan may be helpful in identifying an occult fracture. MRI perhaps may be the most sensitive imaging modality for evaluating traumatic injury in the ankylosed spine. MRI will also allow evaluation for soft disk herniation, epidural hematoma, and intramedullary edema, which may be an indicator of acute fracture. High-resolution multidetector CT (MDCT) imaging has also been described as being more sensitive and accurate in the diagnosis of fractures in AS patients than other contemporary imaging methods and is considered by some to be superior to plain x-ray or MRI.5

Traumatic cervical spinal injury in AS is most often from a hyperextension mechanism, and associated neurological deficit is common.6 Fractures are often transdiskal in nature, with or without involvement of the vertebral body. The C6-7 vertebral level has been described as the most frequent level of injury in several reported series.7 The pattern of injury of the fused cervical column mimics that of a long bone in which a transverse fracture occurs across the entire diameter. In the cervical spine, the fracture can occur across the anterior, middle, and posterior columns. Although the ankylosis often extends through the subaxial cervical spine, the atlantoaxial and occipitocervical articulations may be spared and retain their movement. Because these articulations may be the only remaining mobile joints, they may be subjected to increased shear forces, becoming hypermobile and unstable. As a result, traumatic atlantoaxial or occipitocervical dissociation, with or without an associated odontoid fracture, is more common in patients with AS.8,9

Cervical fractures in patients with AS are often unstable. As mentioned, the ankylosed cervical spine fractures in an atypical fashion, similar to those that occur in tubular long bones. Fractures that are initially nondisplaced can displace suddenly if the neck is extended for immobilization or cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Displacement of fractures and neurological decline has been reported in patients undergoing intubation and emergency immobilization, and during placement of cervical traction and halo vest immobilization.6,10–12

| Authors’ Preferred Method of Surgical Management |

The patient in the clinical scenario underwent a laminectomy and pedicle subtraction osteotomy at C7 for correction of his alignment, with subsequent posterior cervicothoracic fusion from C2 down to T4 for stabilization (Figs. 21–4, 21–5). A laminoplasty at the C3-4 level was also performed to address his myeloradiculopathy. Pedicle screws were used in the upper thoracic spine, and lateral mass screws were inserted into the subaxial cervical spine.

The authors’ preferred management of cervical fractures in patients with AS is based on several factors: the presence or absence of a neurological deficit, progression of neurological decline, fracture pattern and stability, and the overall condition of the patient. Relative stability of the fracture is assumed in patients presenting without signs or symptoms of neurological injury and without history of significant spinal trauma. These patients are initially placed in a hard cervical collar, and a thorough baseline neurological exam is established. Plain radiographs are obtained and should clearly visualize the anatomy of the entire cervical spine and upper thoracic spine to evaluate for potential injury about the cervicothoracic junction. If no fracture is detected but clinical suspicion persists, CT with two-dimensional reconstructions or MRI or both are indicated.

Figure 21–4 Postoperative lateral cervical spine radiograph following C3-4 laminoplasty and C7 laminectomy. A pedicle subtraction osteotomy was performed at the C7 level, and an instrumented posterior arthrodesis was performed from C2 through T4 utilizing lateral mass fixation in the cervical spine and pedicle screw instrumentation in the upper thoracic spine.

In the AS patient presenting with signs or symptoms of myelopathy or radiculopathy, or with a history of significant trauma, immediate cervical immobilization is necessary. Immobilization should be performed after a clinical assessment of the patient’s prefracture sagittal alignment. Patients with significant angulation or displacement at the fracture site should be carefully reduced either by traction, using tongs or a halo, or by immediate application of a halo vest back to their prefracture alignment. One should take great care when placing AS patients with cervical fractures in traction. The fractures can displace and cause neurological deficits. The traction should be in line with the original prefracture neck alignment, and frequent neurological exams are needed. Because of this, one of us (KDR) avoids traction on such patients unless there are no other alternatives. In patients requiring surgical stabilization, our preference is for a posterior approach.13,14 This approach allows for a greater exposure for longer segmental fusions, and the anterior exposure may be difficult secondary to significant cervicothoracic kyphosis. If necessary, posterior decompression can be performed via cervical laminectomy or laminoplasty at the level of the fracture and at levels of existing stenosis. Following decompression, posterior fixation must be performed. Multiple points of fixation must be included both above and below the level of injury to decrease the stress at any single vertebral level in an already osteoporotic spine.13

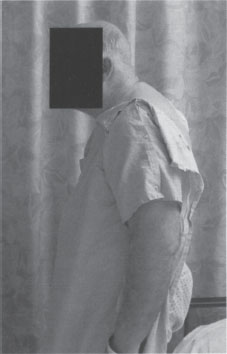

Figure 21–5 Postoperative patient photograph. Note the correction of the cervicothoracic kyphosis achieved.