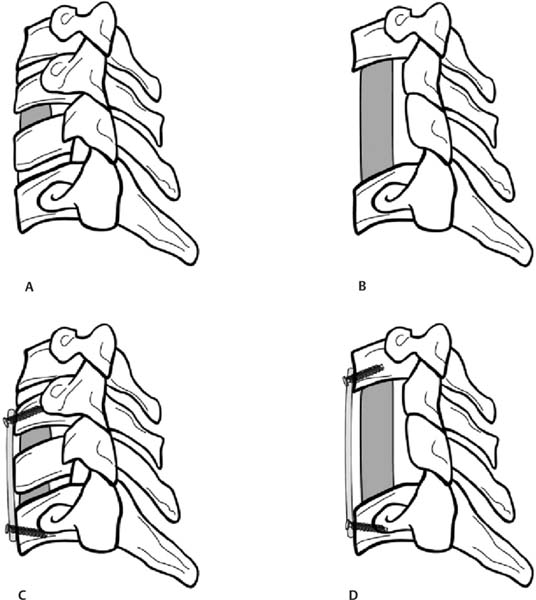

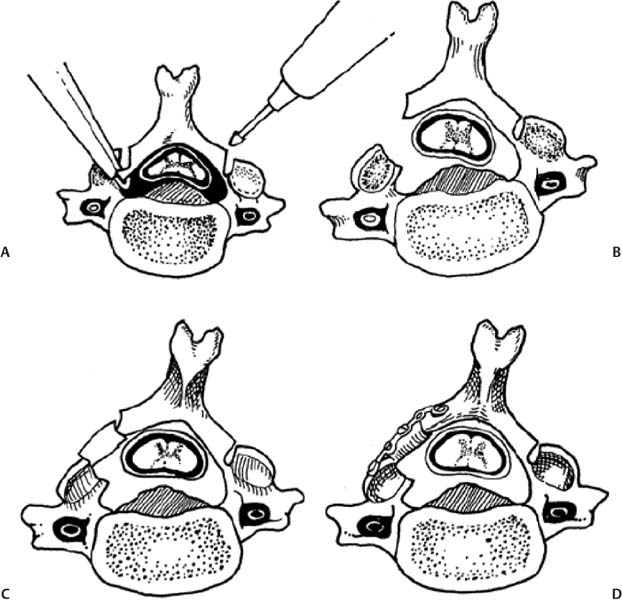

12 Cervical myelopathy is compression of the cervical spinal cord leading to pathognomonic neurological symptoms and physical exam findings. Compression can be secondary to degenerative changes, a herniated disk, trauma, tumor, bleeding, infection, or ossification diseases such as ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) or ossified yellow ligament (OYL). This review focuses on the treatment of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM); that is, myelopathy secondary to degenerative changes. Patients with CSM complain of an insidious onset of impaired balance combined with an awkward gait, clumsiness, diffuse hand numbness/weakness, and impaired fine motor skills.1 Physical exam findings include any combination of motor weakness, increased deep tendon reflexes, clonus, Hoffmann sign, Babinski sign, inverted brachioradialis reflexes (finger flexion with the brachioradialis reflex), and crossed radial reflexes (wrist extension and elbow flexion with biceps reflex).1 Despite the importance of a thorough physical exam, Rhee et al evaluated 39 myelopathic patients and found that 21% did not have classic myelopathic physical exam signs and concluded that the absence of these signs does not preclude the diagnosis of myelopathy or its treatment success.2 In 1956, Clarke and Robinson described the natural course of CSM and found that 75% had stepwise deterioration (new signs/symptoms with variable periods of quiescence), 5% had a rapid onset of disease followed by a long period in which no new features developed, and 20% had a slow steady progression of symptoms.3 Although there is evidence for a trial of nonoperative treatment in the subset of patients with mild or moderate nonprogressive myelopathy,4 operative intervention is indicated for severe or progressive myelopathy with radiographic evidence of spinal cord compression. The goal of operative treatment is to prevent deterioration and possibly to reverse the symptoms of myelopathy by decompressing the spinal cord either anteriorly, posteriorly, or combined and stabilizing it when segmental motion is thought to be a contributing factor.1 The surgical approach is dependent on the nature of pathology, overall cervical alignment, and a surgeon’s familiarity with a given technique. Also critical is an understanding of the clinical outcomes, advantages, disadvantages, and complications of each approach. The treatment of CSM from an anterior approach includes fusion procedures such as an anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF) or corpectomy (Fig. 12.1) and nonfusion procedures such as an oblique corpectomy or cervical disk replacement (CDR). Patients are generally treated with an anterior procedure when there is compression at three or fewer levels or when the spine has a kyphotic alignment.5 Earlier reports of treatment of CSM with an anterior approach led to good clinical results but did not use plate fixation and often implemented halo vest immobilization.6,7 Plating has been shown to increase fusion rates, particularly for two- or more-level ACDFs, with Wang et al reporting an increase in fusion rates from 75 to 100% using autologous iliac crest bone graft (ICBG).8 When allograft is used, plating significantly increases the fusion rate of a two-level ACDF, whereas it may increase the rate of healing of a single-level fusion.9 Groff et al reported on the results of partial anterior corpectomy and plating, which involves resectioning the anterior portion of the intervening vertebrae after adjacent level diskectomies are performed, leaving one third to one half of the posterior portion of the body behind.10 This was done to eliminate the number of fusion surfaces and led to a 96% fusion rate with myelopathy improving in all patients.10 Ying et al reported on 178 cases of CSM randomized to partial anterior corpectomy versus traditional corpectomy followed by autograft and plating with a 100% fusion rate.11 The operative time and blood loss was less in the partial corpectomy group with no differences in segmental lordosis and clinical improvement based on Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scores.11 When a two-level ACDF is compared with a one-level corpectomy, Oh et al reported similar clinical outcomes based on JOA and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores. However, the corpectomy group had a longer operating time, more bleeding, as well as less segmental height and lordosis restoration.12 Fig. 12.1 Common anterior operative interventions used for cervical spondylosis. (A) Anterior cervical diskectomy and insertion of a spacer for fusion. (B) Anterior cervical corpectomy and insertion of a strut bone graft. (C) Anterior cervical diskectomy followed by insertion of a bone spacer for fusion and application of an anterior plate. (D) Anterior cervical corpectomy, insertion of a strut graft, and application of an anterior plate. (From Rao RD, Gourab K, David KS. Operative treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1624. Reprinted with permission.) Kiris and Kilinçer recently reported results of an anterolateral partial oblique corpectomy without fusion for treatment of CSM.13 This procedure involves drilling of the vertebral body from the lateral side where the transverse process intersects with the vertebral body.13 Because neither grafting nor fusion is performed, one of the prerequisites for this procedure is that the intervertebral disks must be hard and collapsed to prevent postoperative instability and kyphosis.13 Ninety-three percent of patients improved by the 6-month follow-up according to the JOA score with maintained improvement at an average of 59-month follow-up.13 However, the far lateral surgical approach led to a 10% rate of permanent Horner syndrome.13 The concern of using motion preservation technology such as a cervical disk replacement (CDR) for myelopathy is the risk of continued microtrauma to the spinal cord. Sekhon was the first to report on the use of a CDR for myelopathy with 6-month follow-up of seven cases using the Bryan CDR14 and subsequent 18-month follow-up of 11 patients.15 The Bryan CDR (Medtronic, Memphis, TN) is an unconstrained articulating polyurethane nucleus between two titanium alloy surfaces. There were no major complications, and there was significant improvement in the Nurick disability index. The study did not compare the results to a control group. Riew et al recently reported the results of the largest series of CDR versus ACDF for treatment of myelopathy.16 This study was a cross-sectional analysis of patients from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) trials with 2-year follow-up for the Prestige ST (Medtronic, Memphis, TN) and Bryan CDR who had a diagnosis of myelopathy from single-level disease due to mild spondylosis or disk herniation. One hundred six patients underwent arthroplasty, and 93 underwent ACDF with allograft and plate fixation. At 2 years, patients in all groups had improvement in neurological status, gait function, and out-come scores. In the Prestige ST trial, 90% of the CDR group and 81% of the ACDF group had improvement in or maintenance of the neurological status. In the Bryan trial, 90% of the CDR and 77% of the ACDF group had improvement in or maintenance of the neurological status in the Bryan trial. This is the first large clinical report which demonstrates that CDR can be used to treat single-level CSM. Complications associated with anterior surgery include pseudarthrosis,17 adjacent-level ossification, particularly with plate placement closer than 5 mm to the adjacent disk space,18 dysphagia secondary to increased esophageal pressure from retraction,19 adjacent-level radiculopathy/myelopathy,20 dural injury,21 vertebral artery injury,22 and pseudarthrosis.23 Posteriorly based techniques include laminoplasty, laminectomy, or laminectomy and fusion. These procedures are most frequently used in a lordotic spine that has compression at four or more levels, a congenitally stenotic canal, or a fused anterior column.5 Several variations of the laminoplasty technique, all of which expand the canal and avoid fusion, were introduced by the Japanese for treatment of myelopathy associated with OPLL24–26 (Fig. 12.2). Satomi et al reported on the results of 204 patients who underwent unilateral open-door laminoplasty with greater than 5-year follow-up in 80 patients.27 The recovery rate for the subset of patients with CSM was 64%. Patients younger than 60 years and with less than 1 year of symptoms were associated with the better recovery.27 Kawaguchi et al reported on the 10- year outcomes following laminoplasty in 126 patients and found that the JOA recovery rate was 55%.28 However, several postoperative complications were encountered, including radiculopathy (7%), kyphosis (6%), and a decrease in range of motion (ROM) to 25% of preoperative motion.28 Aita et al also found that laminoplasty was associated with kyphosis and loss of ROM from 40 degrees preoperatively to 13 degrees at 5-year follow-up.29 Other authors have found that kyphosis leads to poorer clinical outcomes,30,31 and that a mean posterior spinal cord shift of > 3 mm is associated with better clinical outcomes based on JOA scores.32 As such, an absolute prerequisite for laminoplasty or any posteriorly based procedure is lordotic alignment of the cervical spine, or the ability to obtain lordosis for a laminectomy and fusion, to allow the spinal cord to float away from the anterior structures. Fig. 12.2 Operative technique for modified open-door laminoplasty. (A) Bilateral gutters created with a combination of a high speed burr and a 1 mm Kerrison rongeur. (84). (B) Green-stick osteotomy. (C) Placement of bone graft with notching to lock it into place. (D) Stabilization can be augmented with the use of a miniplate. (From Shaffrey CI, Wiggins GC, Piccirilli CB, Young JN, Lovell LR. Modified open-door laminoplasty for the treatment of neurological deficits in younger patients with cations through careful preoperative congenital spinal stenosis: analysis of clinical and radiographic data. J Neurosurg 1999;90(Suppl 2):170–177. Reprinted with permission.) Axial neck symptoms following laminoplasty have been reported by several authors.33,34 In 72 patients treated for CSM with laminoplasty at an average follow-up of 40 months, 60% had postoperative axial symptoms, and in 25% of patients, the chief complaints after surgery were related to axial symptoms for more than 3 months.33 Some authors have proposed methods to decrease axial neck pain by modifying the traditional laminoplasty techniques, including preservation of the C7 spinous process35 or the semispinalis cervicis insertion onto C2.36 Despite these efforts aimed at preserving posterior musculature, axial neck pain was still present in 47% of patients postoperatively.36 Decompression of the spinal canal by laminectomy or removal of the lamina has been reported to successfully treat compression secondary to OPLL.37,38 Miyazaki and Kirita reported the results of 155 patients who underwent laminectomy and found that 82% showed improvement based on JOA scores at 1-year follow-up.37 However, Kato et al reported longer follow-up of patients following laminectomy and demonstrated that only 33% had neurological recovery at 10 years, with late neurological deterioration in 23% of patients.38 After the laminectomy, postoperative progression of a kyphotic deformity was observed in 47% of patients.38 Several authors have also reported kyphosis following laminectomy,39–41 with Herkowitz40 and Kaptain et al41 reporting a 25% and 21% incidence, respectively, at 2-year follow-up. Kaptain et al found that kyphosis was twice as likely to occur if preoperative imaging studies demonstrated a straight spine.41 The treatment of postlaminectomy kyphosis involves a fusion procedure to prevent worsening of the deformity.42,43 Callahan reported on the results of 63 patients with postlaminectomy kyphosis who underwent posterior fusion with wiring of the facets with ICBG and found that 96% of patients had a solid fusion at 6.5 months.42 Another common complication of posteriorly based procedures is postoperative C5 nerve root palsy, although it has been reported in both anterior and posterior cases. Following laminectomy, Dai et al reported a rate of 12.9%, with the most frequent pattern being C5 or C6; the mean time for recovery was 5.4 months.44 The risk of postlaminectomy kyphosis and destabilization has led many authors to recommend a fusion procedure if a laminectomy is performed.45 Successful clinical outcomes have been reported by authors who treated myelopathic patients with a laminectomy followed by an uninstrumented46 or sublaminar wire fusion.47 Kumar reported on the outcomes of 25 patients treated for CSM by laminectomy and lateral mass screw and plating with at least 2-year follow-up.48 There was no development of kyphosis or instability, and 76% had improved myelopathy scores. Huang et al reviewed the outcomes of 32 patients with myelopathy secondary to spondylosis or OPLL treated by laminectomy and lateral mass screw and plate fixation with local bone graft49 (Fig. 12.3). At a mean of 15-month follow-up, 97% of patients fused, and 71% had an improvement in their Nurick grade of at least one point.49 Houten and Cooper reported on 38 patients who underwent laminectomy and lateral mass screw with plating for CSM or OPLL with a mean of 30-month follow-up.50 There were no changes in cervical alignment based on the curvature index between the preoperative and 5.8-month follow-up.50 The JOA score improved in 97% of patients from a mean of 12.9 preoperatively to 15.6 postoperatively.50 Use of lateral mass screws for a laminectomy and fusion have been associated with a considerably low rate of complications compared with in vitro studies, even with bicortical screw purchase.51 Complications include nerve root injury (0.6%), facet violations (0.2%), broken screws (0.3%), screw loosening (1.1%), infection (1.3%), and pseudarthrosis (1.4%).51 Despite its widespread use, we are not aware of any studies that examine the clinical or radiographic outcomes of a posterior cervical laminectomy and fusion using a screw–rod construct for CSM. In addition, the use of lateral mass and pedicle screws in the cervical spine is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Clinical trials comparing posteriorly based procedures are sparse. Yukawa et al reported on the results of one prospective, randomized study comparing laminoplasty to skip laminectomy.52 Skip laminectomy is decompression of the spinal cord by removing the hypertrophic ligamentum flavum and the cephalad portion of the inferior lamina while leaving the other structures intact, theoretically preventing postlaminectomy kyphosis.52 Forty patients were randomized to laminoplasty or skip laminectomy and followed for more than 1 year.52 The final range of motion was ~80% of the preoperative ROM for both groups, and there were no differences in JOA scores or incidences of axial neck pain.52 It is important to note that skip laminectomy is a selective decompression and should ideally be used in patients with OYL and not in patients who have diffuse compression and OPLL.52 Lamifuse is a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial that was proposed in the Netherlands in 2007 and will evaluate laminectomy with or without dorsal fusion for cervical myelopathy.53 Heller et al, in a well-matched cohort analysis, compared 13 patients who had laminoplasty to 13 patients with laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass plating for multilevel CSM with ~25-month follow-up. Both objective improvement in patient function (Nurick score) and the number of patients reporting subjective improvement in strength, dexterity, sensation, pain, and gait tended to be greater in the laminoplasty cohort.54 Complications included progression of myelopathy, nonunion, instrumentation failure, development of a significant kyphotic alignment, persistent bone graft harvest site pain, adjacent degeneration requiring reoperation, and deep infection.54 Interestingly, the presence of axial neck pain was the same in both groups54 Fig. 12.3 Laminectomy and fusion using lateral mass screws and plate. Note that an absolute prerequisite is the ability to achieve lordosis on a preoperative lateral extension x-ray. (From Huang RC, Girardi FP, Poynton AR, Cammisa Jr FP. Treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy with posterior decompression and fusion with lateral mass plate fixation and local bone graft. J Spinal Disord Tech 2003;16:123–129. Reprinted with permission.) (A) AP view. (B) Lateral view. There are no level I studies available. There are no level II studies available. There are seven level III studies which compare the functional or radiographic outcomes of anterior versus posterior surgery for CSM (Table 12.1).33,55–61 One level III study compares the results of anterior versus posterior treatment in the setting of OPLL.61 Several of these studies are difficult to interpret secondary to heterogeneity of surgical techniques,56 assignment of a different surgical approach based on levels of pathology,58,59,62 and the lack of internal fixation with anterior corpectomy procedures.57–59,61,62 Hukuda et al reported on the minimum of 1-year outcomes of three anterior and three posterior techniques used to treat 269 patients with CSM.56 The large variety of procedures and the inclusion of patients with spinal cord injury syndromes make it difficult to draw conclusions regarding anterior versus posterior techniques.56 After isolating patients with advanced myelopathies into the type of presenting incomplete cord syndromes (e.g., Brown-Séquard syndrome), those who had a posterior procedure had significantly worse preoperative JOA grades compared with those who had an anterior procedure. However, there were no differences in JOA grade at final follow-up.56 Yonenobu et al examined the differences in neurological complications in 384 cases of myelopathy secondary to disk herniation, spondylosis, or OPLL treated with ACDF (134 patients), corpectomy (70 patients), laminectomy (85 patients), or laminoplasty (95).55 There was a 10% incidence of C5 nerve root palsy and a 6% incidence of spinal cord dysfunction postoperatively.55 The incidence of neurological complication was not attributable to whether an anterior or posterior surgery was performed.55 Table 12.1 Summary of Level III Data on Anterior versus Posterior Surgery for Cervical Myelopathy

Cervical Myelopathy: Anterior versus Posterior Approach

Posterior Approaches

Posterior Approaches

Anterior versus Posterior Approaches

Anterior versus Posterior Approaches

Level I Studies

Level II Studies

Level III Studies

Author | Treatment Groups | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

Hukuda et al56 | Three different anterior procedures versus three different posterior procedures | • Minimum of 1-year outcome on 269 patients with CSM • Included patients with spinal cord injury • Posterior procedure patients had a worse JOA grade preop • No differences in JOA grade at final follow-up |

Yonenobu et al62 | ACDF versus corpectomy versus laminectomy | • Posterior procedure was done for four or more levels of compression • JOA score gain and rate of improvement better in the corpectomy than ACDF or laminectomy group • Neurological deterioration in laminectomy group secondary to progressive kyphosis (no hardware was used) • 45% nonunion in ACDF group particularly with three-level surgery (no hardware was used) |

Yonenobu et al57 | Corpectomy with iliac crest autograft versus laminoplasty | • Similar number of pathological levels for patients with anterior or posterior procedures • Two-year outcome with no differences in recovery rate and postoperative JOA scores • Four times as many complications in corpectomy group secondary to graft problems (no hardware was used) |

Kawakami et al58 | Anterior decompression versus laminoplasty | • Posterior approach if three or more levels were involved or presence of developmental stenosis • No differences in JOA recovery rates between two groups |

Wada et al59 | Anterior corpectomy versus laminoplasty | • Average follow-up longer than 10 years • Both groups with improvement and maintenance of JOA scores versus preop • Significantly more axial neck pain in the laminoplasty group • 29% nonunion rate in corpectomy group (no hardware was used) |

Edwards et al60 | Anterior corpectomy versus laminoplasty | • Strict inclusion criteria with all patients with three or more levels of disease • 23 patients in corpectomy group, 24 patients in laminoplasty group • Mean follow-up longer than 40 months • No differences in improvement between two groups on all clinical outcomes • Similar prevalence of axial neck pain between both groups |

Iwasaki et al61 | Anterior corpectomy versus laminoplasty | • 27 patients in corpectomy group, 66 patients in laminoplasty group • Corpectomy patients had a better neurological outcome versus laminoplasty only in patients with an occupying ratio of > 60% (typical of OPLL) • 15% graft complication rate with corpectomy (no hardware used) |

Abbreviations: ACDF, anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion; CSM, cervical spondylotic myelopathy; JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association; OPLL, ossified posterior longitudinal ligament.

Hosono et al examined the differences in functional outcome and axial symptoms (neck and shoulder pain) following ACDF (26 patients) versus laminoplasty (72 patients) for CSM.33 At an average follow-up of 53 months, there were no differences in the JOA score at final follow-up between the two groups.33 However, there was a significantly higher incidence of axial neck pain after laminoplasty when compared with the ACDF group (60% vs 19%).33 In 25% of patients from the laminoplasty group, the chief complaint after surgery was related to axial symptoms for more than 3 months.33

Yonenobu et al evaluated the results of ACDF (50 patients), corpectomy and fusion (21 patients), and C3–C7 laminectomy (24 patients) in patients with multisegmental CSM.62 The treatment was not randomized, and the decision for a posterior procedure was made in cases of four or more levels of compression with a lordotic spine.62 The JOA score gain and rate of recovery were statistically better in the corpectomy group when compared with the ACDF and laminectomy groups.62 Neurological deterioration in the laminectomy group was secondary to the development of a kyphotic deformity.62 Complications in the ACDF group included nonunions, particularly with three-level surgeries (45%).62 Notably, internal fixation was not used for the anterior procedures, making it difficult to apply the results to current management of CSM because plate fixation is now routinely used. A subsequent study from the same institution investigated outcomes of corpectomy with iliac crest autograft (41 patients) versus laminoplasty (42 patients) for multisegmental CSM.57 Unlike the prior study, the two groups were similar with regard to the number of pathological levels. At 2 years, there were no differences between recovery rate and postoperative JOA scores between the two groups.57 However, there were four times as many major complications in the corpectomy group, mostly related to bone grafting such as dislodgment, fracture, or nonunion.57 Alignment worsened in 14% of patients who had a laminoplasty, but none of them had neurological deterioration.57 The authors concluded that because of the high rate of graft-related complications, laminoplasty should be the treatment of choice for multisegment CSM.57 However, plate fixation was not used in this study, thereby dampening the clinical relevance as current techniques involve anterior decompression followed by instrumentation.

Kawakami et al compared the 2-year results of patients with myelopathy treated with an anterior decompression without instrumentation (60 patients) versus laminoplasty (76 patients).58 Patients with myelopathy secondary to a herniated disk as well as spondylosis were included in the study.58 Although all patients were myelopathic, the decision for an anterior versus posterior treatment was not randomized but was largely based on the number of levels of pathology involved. Patients with one or two levels of disease were treated anteriorly, whereas those with more than three levels of disease or developmental stenosis (anterior posterior diameter < 13 mm) were treated posteriorly.58 The hetero-geneity in baseline characteristics (both levels and etiology of myelopathy) between the two groups makes it difficult to assess efficacy of treatment.58 For patients with spondylosis, there were no significant differences in the mean JOA recovery rates between the anterior and posterior groups (49% and 59%, respectively).58 Although none of the patients treated posteriorly had a kyphotic deformity preoperatively, 11% of patients had kyphosis at final follow-up.58 The authors also used postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to establish whether the spinal cord itself was in a lordotic, straight, or kyphotic position.58 They demonstrated that a lordotic cervical spine does not necessarily yield a lor-dotic spinal cord as only 87% patients with a lordotic cervical spine had a lordotic spinal cord in patients who received a posterior procedure.58

Wada et al reported on the long-term outcome of patients with multilevel CSM treated with corpectomy (23 patients) versus laminoplasty (24 patients).59 It should be noted that despite the inference of “multilevel” pathology, patients received a range of one to three corpectomies, with the average fusion segment being 2.5 interspaces indicating that not all patients had three or more levels of pathology.59 The average follow-up in the corpectomy and laminoplasty group was 15 and 12 years, respectively.59 Both groups had significant maintenance and improvement in JOA scores by ~5 points compared with preoperative values up to the final follow-up period.59 No significant differences in neurological recovery were found between the two groups at all follow-up time periods.59 There were statistically more patients in the laminoplasty group with axial neck pain compared with the corpectomy group (40% vs 15%, respectively).59 ROM in the corpectomy group decreased by 49% at final follow-up compared with 29% in the laminoplasty group. The nonunion rate in the corpectomy group was 26% with all of them requiring posterior wiring. However, similar to other studies within that time period, plate fixation was not used in patients who had a corpectomy. A kyphotic deformity developed in 9% and 13% of patients in the corpectomy and laminoplasty groups, respectively.59 The operative time in the corpectomy group was significantly longer than the laminoplasty group.59

Edwards et al compared the results of corpectomy (13 patients) versus laminoplasty (13 patients) in multilevel CSM.60 Strict inclusion criteria were applied, and only patients with three or more levels involved were included and patients were matched according to age, duration of symptoms, and sagittal alignment.60 This is the first study comparing anterior to posterior approaches in which the corpectomy graft was held in place by an anterior plate.60 The mean follow-up for the corpectomy and laminoplasty groups was 49 and 40 months, respectively.60 There were no differences in operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay.60 Improvement in function averaged 1.6 Nurick grades after laminoplasty and 0.9 grades after multilevel corpectomy.60 Subjective improvements in strength, dexterity, sensation, pain, and gait were similar for the two operations.60 The prevalence of axial discomfort at the latest follow-up was the same for each cohort.60 Sagittal motion from C2 to C7 decreased by 57% after multilevel corpectomy and by 38% after laminoplasty.60 Multilevel corpectomy complications included progression of myelopathy, nonunion, persistent dysphagia, persistent dysphonia, and adjacent segment ankylosis.60 This study is the first to strictly match patient cohorts and levels of pathology and supports laminoplasty in patients who have three or more segments of compression and a lordotic spine. Unfortunately, the study is limited by its retrospective nature and a small number of patients in each group.

Iwasaki et al reported on the results of corpectomy (27 patients) versus laminoplasty (66 patients) in the setting of OPLL.61 Although no definitive criteria were used to select whether or not someone received an anterior or posterior procedure, patients who had massive ossified lesions, hill-shaped ossification, and sharp angulation of the spinal cord received an anterior procedure.61 Corpectomies were done at two to five levels as determined by the extent of compression.61 Anterior instrumentation was only used in one patient, and immobilization with a halo vest was used for a mean of 8 weeks after surgery. Sixty-five percent of patients in each group had an excellent/good neurological recovery rate.61 Additional surgery was required in 26% of patients in the anterior group and 2% of patients in the posterior group.61 Despite the higher rate of additional surgery and a 15% graft complication rate, corpectomy yielded a better neurological outcome at final follow-up than laminoplasty only in patients with an occupying ratio ≥ 60% (54% vs 14%, respectively). The occupying ratio was calculated as the ratio of the maximum anteroposterior thickness of OPLL to the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal at the corresponding level on a lateral radiograph or computed tomography.61 The authors suggest that OPLL with an occupying ratio ≥ 60% should be treated with an anterior procedure rather than laminoplasty despite its higher rate of complication.61

Consensus of Society Statement

Consensus of Society Statement

There are no society consensus statements regarding anterior versus posterior surgical approaches for cervical myelopathy.

Conclusions

Conclusions

There is no level I or II evidence comparing anterior versus posterior approaches for treatment of cervical myelopathy. Level III evidence comparing anterior procedures to laminoplasty, although flawed by heterogeneity of surgical technique and levels of pathology, seem to indicate that patients have similar neurological outcomes regardless of approach. In general, patients with more than three levels of compression and a lordotic spine received a posterior procedure (laminoplasty, laminectomy, laminectomy, and fusion), and those with three or fewer levels received an anterior decompression (ACDF, corpectomy). Patients undergoing laminoplasty seem to have more axial neck pain but more ROM when compared with multilevel corpectomies. However, true differences remain to be established because there is a lack of studies with a large number of matched cohorts of patients. In addition, despite the widespread use of laminectomy and fusion with instrumentation, there are no studies that compare anterior procedures to a laminectomy and fusion for treatment of CSM.

Pearls

• Large-scale randomized, prospective trials comparing anterior approaches to laminoplasty or laminectomy with fusion are needed to establish clinical guidelines for treatment of multisegment CSM.

• Anterior procedures such as multilevel diskectomy or corpectomy are suitable for less than four levels of compression or when there is kyphosis but are associated with more complications than posterior procedures.

• Posterior procedures require a lordotic cervical spine and are suitable when there are four or more levels of compression or a congenitally stenotic canal.

• Posterior procedures should be combined with a laminoforaminotomy if there is arm pain associated with myelopathy.

• Despite good clinical results, laminoplasty is often associated with increased axial neck pain when compared with anterior procedures and a decrease in ROM.

• Laminectomy without fusion is associated with postlaminectomy kyphosis and is generally not recommended.

• Despite its common use and clinical success, laminectomy and fusion with lateral mass/pedicle screw fixation is non-FDA approved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree