Axial FLAIR and T1 with gadolinium MRI brain shows abnormal signal within the left tegmentum of the pons with patchy peripheral enhancement without mass effect, with scattered T2 hyperintensity in the periventricular deep white matter of both hemispheres consistent with multiple sclerosis with active brainstem demyelination.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: painless binocular diplopia, asymmetrical limb incoordination

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS; MRI cervical spinal cord MRI consistent with MS; CSF consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis.

Tip: Occasionally symptoms of demyelination may have a sudden onset and brief duration, thereby mimicking a cerebrovascular cause. Evaluations in this patient revealed additional evidence of demyelination in the brain and cervical spinal cord as well as CSF abnormalities consistent with MS.

Case 51: Progressive gait impairment in a woman on chronic anticoagulation therapy

A 64-year-old woman presented with progressive numbness, weakness and gait ataxia over the prior two and half years. She recalled initially developing numbness in the left foot which progressed up the left lower extremity and then involved the right lower extremity. She had no cognitive impairment or hearing loss. She started to use a cane and then a walker, but despite that continued to experience falls.

On neurological examination, her visual fields and extraocular movements were normal. She had moderate quadriparesis in the upper and lower extremities. Her reflexes were intact in the upper extremities and markedly reduced in the lower extremities with bilateral extensor plantar responses. There was severe, multiple modality sensory loss in the lower extremities. She had also severe gait impairment and needed bilateral assistance to stand.

Brain, cervical and thoracic spine MRIs showed no evidence of MS but did show hemosiderin deposit throughout (Figure 8.2). A CSF examination showed a white cell count of 40 with 712 red blood cells and marked xanthochromia. CSF protein was elevated at 83 mg/dL, while her oligoclonal bands, IgG index NMO-IgG and paraneoplastic autoantibody screen were all normal. Serological testing for NMO-IgG antibodies, ferritin, and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) were all normal.

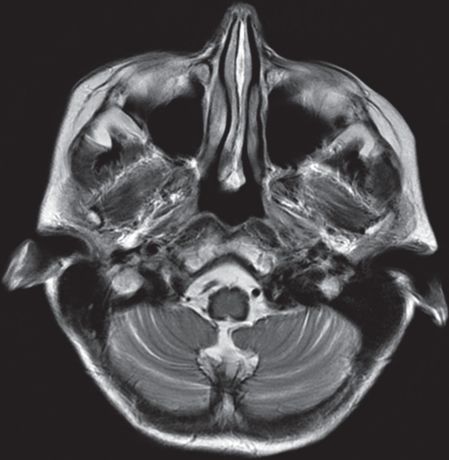

Axial FLAIR MRI brain shows T2 hypointensity surrounding an atrophic brainstem and into cerebellar folia consistent with superficial siderosis.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: progressive myelopathy with gait ataxia

2 Neurological examination: consistent with myelopathy

3 Investigations: brain, spinal cord MRI negative for MS but consistent with other neurological disease – superficial siderosis; CSF consistent with superficial siderosis

Diagnosis: Superficial siderosis.

Tip: A typical clinical presentation of superficial siderosis is an older patient with risk factors for bleeding. A typical presentation would be hearing loss, dementia and significant ataxia. It is important to look for siderosis to rule out changes of primary progressive multiple sclerosis as a cause for significant progressive gait impairment.

Case 52: A young man with personality change, ataxia and progressive brain white matter changes

A 20-year-old gentleman presented with significant personality change and ataxia over a number of years. He was the product of a normal pregnancy and delivery and met his early developmental milestones as expected. By fourth grade he was declining academically, and by sixth grade he had incoordination and imbalance. In his teenage years he had impaired judgment and problems with impulse control, resulting in his being fired from his job for socially inappropriate behavior. He developed dysphagia and hypernasal speech and became progressively less intelligible. A paternal uncle had multiple sclerosis and his maternal great-grandfather had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

On neurological examination, he was short in stature with a head circumference of 58.0 cm (normal adult head circumference is 55.9 cm with a standard deviation of 1.85 cm). He scored 31 out of 38 on a short test of mental status. He had horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus with evidence of palatal myoclonus (palatal tremor). His motor power was normal as was his sensation, but his tandem walking was ataxic.

A brain MRI showed multiple areas of abnormal T2 signal in the white matter diffusely and confluent with a frontal predominance (not shown). Importantly, there was significant atrophy of the medulla and pons with signal abnormality (Figure 8.3). There was persistent gadolinium enhancement involving the cerebellar peduncle on the right side. Genetic testing confirmed evidence of a mutation in the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) gene, confirming Alexander disease.

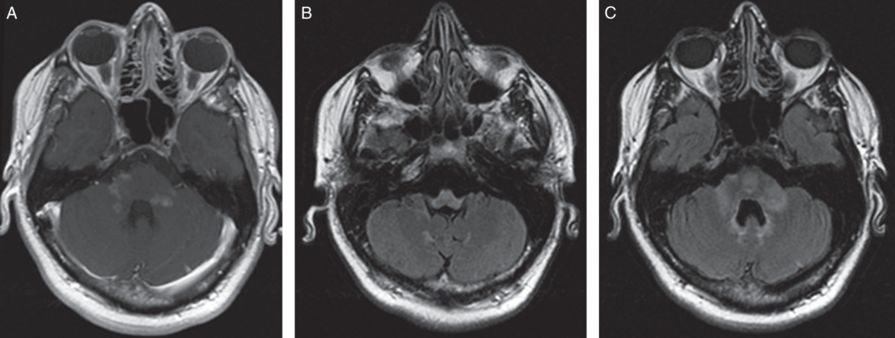

Axial FLAIR and T1 with gadolinium MRI brain shows confluent areas of abnormal T2 hyperintensity involving the central pons, middle cerebellar peduncles, dentate nuclei and medulla with associated patchy enhancement, particularly of the cerebellar peduncle and medullary lesions with marked medullary atrophy.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: progressive cognitive and brainstem dysfunction

2 Neurological examination: ataxia and cognitive impairment with palatal myoclonus (palatal tremor), macrocephaly

3 Investigations: brain, spinal cord MRI negative for MS; consistent with other neurological disease – genetic testing confirmed mutation in the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) diagnostic of Alexander disease

Diagnosis: Alexander disease.

Tip: The key diagnostic points in this case are of a frontal predominant white matter disease with severe medullary atrophy and enhancement. The evidence of palatal myoclonus on examination, as well as the ataxia, is consistent with Alexander disease. Some patients presenting in adulthood may not have macrocephaly. The GFAP mutation analysis is diagnostic, as it was in this case.

Case 53: A young man with rapidly progressive impairment and brainstem hemorrhage

A 20-year-old man, who was otherwise well and with no prior medical illnesses, presented with acute onset of lower extremity paresthesias, painless binocular diplopia, gait ataxia, left facial weakness and dysarthria. He had no prodromal constitutional symptoms and no fever, headache, ill contacts, or recent travel. His symptoms rapidly worsened over days; he suffered from progressive respiratory compromise and required mechanical ventilation.

On neurological examination he was intubated and sedated with quadriparesis and an essentially “locked-in” state.

He was treated with corticosteroids, plasma exchange and intravenous cyclophosphamide but did not respond and died soon after.

Serial brain MRIs showed a progressively enlarging area of abnormal T2 signal within the brainstem with gadolinium enhancement. Progressive expansion of the lesion and ring enhancement was then associated with subtle subacute hemorrhage. A subsequent brain MRI demonstrated severe necrosis with gross hemorrhage (Figure 8.4). Cervical and thoracic spine MRIs were both normal as was a brain MR angiography. A CSF examination showed 25 white blood cells (51 percent monocytes, 41 percent lymphocytes). Protein was elevated at 70 mg/dL. His IgG index was elevated to 1.64, but there were no unique CSF oligoclonal bands. Tests for infectious agents, including listeria, fungal, bacterial, microbacterial cultures, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6 and Whipple’s agent polymerase chain reaction (PCR), were all negative. The autopsy confirmed evidence of a hemorrhagic necrotizing inflammatory process consistent with acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (Hurst) disease.

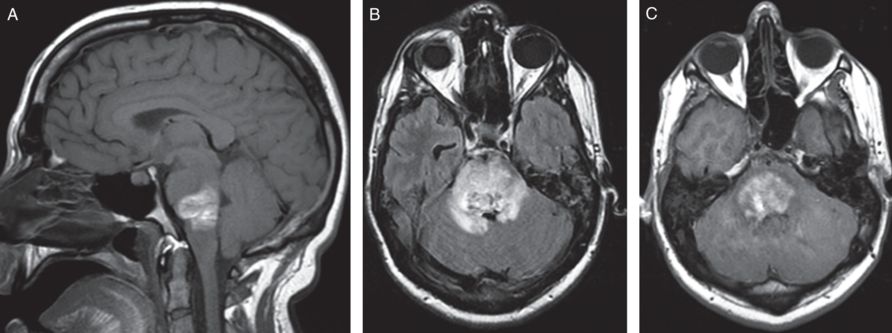

Sagittal T1 without gadolinium, Axial FLAIR and T1 with gadolinium MRI brain shows extensive area of increased T1 and decreased T2 signal consistent with subacute hemorrhage, increased T2 signal with an irregular ring of enhancement, with mass effect in the pons, and extension of signal abnormality into the middle cerebellar peduncles.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: acute progressive brainstem dysfunction; severe, treatment resistant

2 Neurological examination: progressive findings of severe brainstem dysfunction with respiratory compromise

3 Investigations: brain MRI: severe demyelinating disease with hemorrhage; spinal cord MRI: negative for MS; CSF consistent with CNS demyelinating cause; autopsy confirmed acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (Hurst) disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree