Axial FLAIR MRI brain showed several scattered foci of T2 hyperintensity in the white matter that were nonspecific in appearance and unchanged over 8 years of follow-up.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: monocular, painless visual loss, uncertain optic neuritis

2 Neurological examination: normal without significant optic neuropathy

3 Investigations: MRI brain not consistent with MS; CSF not consistent with MS; visual evoked potentials normal; follow-up not consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Visual loss, no definite MS diagnosis.

Tip: A watchful waiting approach is sometimes extremely beneficial when the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis remains uncertain. Repeating clinical and radiological evaluations over time to assess for the development of more definitive changes of multiple sclerosis is important. Avoiding directed immunomodulatory therapy aimed at MS is important where diagnostic uncertainty remains. The patient had no dissemination of symptoms, non-specific MRI findings and a normal CSF over ten years of follow-up not meeting MS criteria.

Case 29: Is it papillitis (optic neuritis) or papilledema?

A 36-year-old gentleman was found to have a bilateral optic nerve head edema of uncertain etiology.

The patient was aware of visual symptoms for one and a half months. He described episodes of his vision “fading out,” where his visual fields would constrict from the periphery inward from both eyes simultaneously. On some occasions only the extreme peripheral vision would darken and at other times his vision bilaterally would be lost completely. The visual impairment would last less than ten minutes with the vision then resolving entirely back to normal. Leaning his head and body forward and turning his head to one side could initiate the visual disturbance. The visual symptoms were not associated with seeing scintillating scotoma, waves, jagged edges or fortification spectra, and he had no ptosis or diplopia. He had no headache or pulsatile tinnitus and had no prior symptoms of hemiparesis, hemisensory deficit or loss of consciousness, and even during the spells his mental status remained entirely normal. He had a sedentary lifestyle and had gained 40 pounds of weight over the prior year.

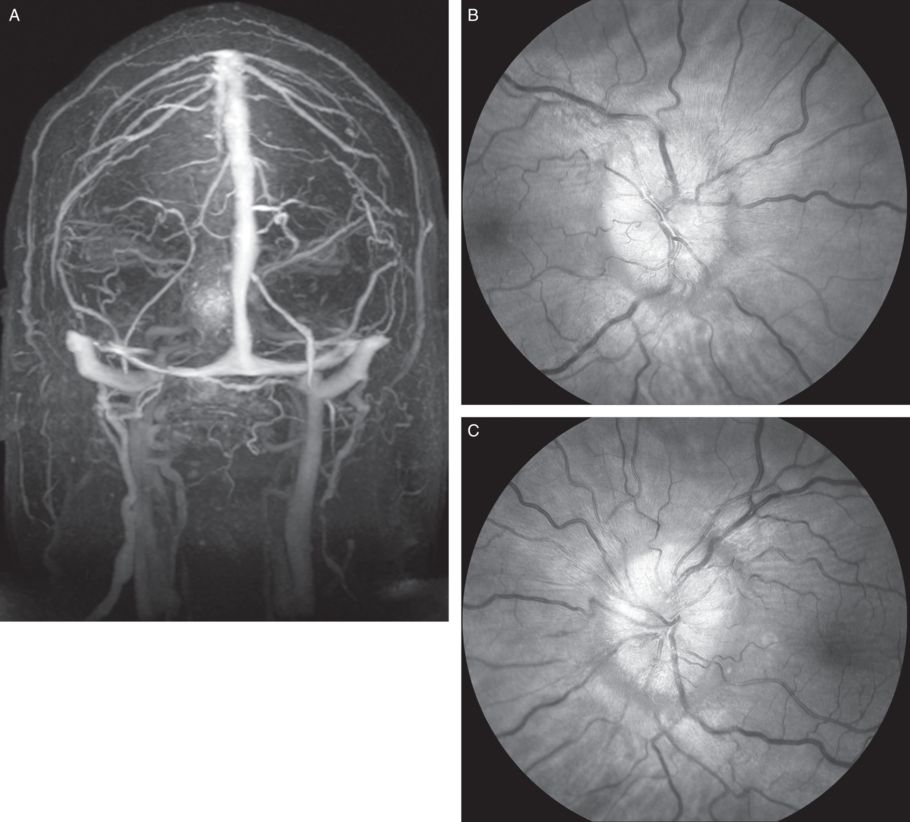

On neurological examination, visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/20–1 in the left eye with normal color vision bilaterally and no afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressures were normal bilaterally. A dilated funduscopy showed an optic nerve head edema with small flame hemorrhages extending beyond the optic nerve in both eyes (Figure 5.2 B,C). Retinal periphery was normal. The rest of his neurological examination was normal.

A) MR Venography showed both transverse sinuses were narrowed without evidence of thrombosis. This can be seen with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. An MRI brain scan showed no evidence of intracranial mass lesions. B,C) An ophthalmological examination showed a bilateral disc edema; a lumbar puncture opening pressure was 420 mm H20.

A brain MRI scan did not show any intracranial mass lesions or other signal abnormality of significance but showed radiological evidence of bilateral papilledema with dilatation of the optic nerve sheaths. MR venography showed no evidence of venous thrombosis but the transverse sinuses were narrowed bilaterally (Figure 5.2 A). A CSF examination was normal apart from the documented opening CSF pressure of 42 cm of H2O. Serological testing excluded syphilis, ehrlichia and Lyme disease as the possible cause.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: visual symptoms atypical for optic neuritis (positional, bilateral, transient, painless visual obscurations of brief duration)

2 Neurological examination: optic nerve head edema bilaterally without acuity loss or color vision impairment

3 Investigations: MRI brain not consistent with MS; CSF not consistent with MS with elevated opening CSF pressure

Diagnosis: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri).

Tip: an enlarged optic nerve head due to “papillitis,” that is, optic neuritis is typically associated with severe loss of visual acuity and color vision impairment. Papilledema from increased intracranial pressure may be associated with transient visual obscurations, as in this patient, as well as enlargement of the physiological blind spot but unless this is extremely severe, it is less likely to cause visual acuity deficit despite the marked optic nerve head edema seen.

A brain MRI scan ruled out demyelinating lesions of MS and any significant intracranial mass lesion. An MR venography ruled out any significant sinus venous thrombosis, which can cause a similar picture. Documentation of definitive elevated CSF opening pressure, as was performed in this case, is essential in making the diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri.

The patient was started on acetazolamide 500 mg by mouth twice daily. This may have an effect on carbonic anhydrase inhibition to reduce CSF pressure. It also may cause reduced appetite, and be associated with beneficial weight loss.

Case 30: An elderly woman presenting with rapid and severe bilateral visual loss

A 78-year-old woman presented with a nine-day history of progressive, severe, bilateral and painless visual loss, essentially equivalent in the right and left eyes. She rapidly became functionally blind over the two days prior to presentation. She had no prior history of visual loss and had no history of diplopia, hemiparesis, hemisensory deficit, symptoms of sensory myelopathy, gait impairment or bowel or bladder dysfunction.

On neurological examination it was found that she had severe, bilateral blindness with poorly responsive pupils without any optic nerve head edema (papilledema). The rest of her neurological examination was normal.

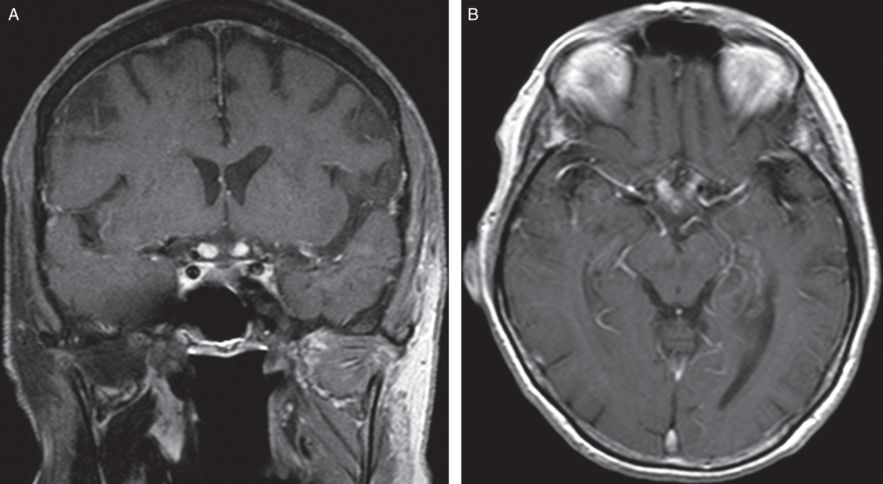

A brain MRI showed a gadolinium-enhancing lesion involving both optic nerves and the optic chiasm (Figure 5.3). Age-appropriate small vessel ischemic changes were seen in the brain’s white matter but none were suggestive of MS. A CSF examination showed no unique oligoclonal bands or elevated IgG index. Serum paraneoplastic autoantibodies were negative. Serum SS-B antibodies were minimally elevated but a salivary gland biopsy showed no diagnostic features of Sjögren syndrome. Serum NMO-IgG (aquaporin-4) antibodies were positive.

Coronal and Axial T1 with gadolinium MRI brain and optic nerves shows marked gadolinium enhancement of the posterior optic nerves and into the optic chiasm.

She was treated with 1000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone for five days. She was started on treatment with azathioprine after serum thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) enzyme level assessment was found to be adequate. She experienced marked improvement with good functional vision regained. She remained on chronic immunosuppressive medications to reduce the likelihood of recurrent NMO spectrum disorder attacks even following a single clinical attack.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: acute optic neuropathies, atypical for MS-related optic neuritis (very severe, painless and bilateral at onset)

3 Investigations: MRI brain not consistent with MS with optic chiasm involvement; CSF not consistent with MS; NMO-IGG antibody positive

Diagnosis: Bilateral severe optic neuritis related to neuromyelitis optica (NMO) spectrum disease.

Tip: Optic nerve and optic chiasmal lesions with severe optic neuropathies, particularly bilaterally, can suggest neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease. Patients with elevated NMO-IgG antibodies are at higher risk of developing new clinical attacks of neuromyelitis optica and so should be considered strongly for the use of long-term immunosuppressive medications.

Case 31: A young woman with headaches, optic nerve head edema and abnormal brain MRI

A 33-year-old woman with a history of migraine and rheumatoid arthritis on no medications presented with a three-week history of new onset visual symptoms. She described “floaters” in her right eye which then went on to involve the left eye, which were constantly present and progressively spread throughout her vision. On some occasions she had seconds where her vision seemed “all fuzzy” all over, and this progressed to a point where she had had difficulty reading and seeing a computer screen. She had had moderate headaches that had worsened over the prior three weeks. She had mild gait imbalance and felt non-specific weakness in her legs and rare spells of paresthesias in random distributions. She had no fever or contact with sick people, and did not travel to a significant degree. She had had some intermittent spells of paresthesias in different distributions.

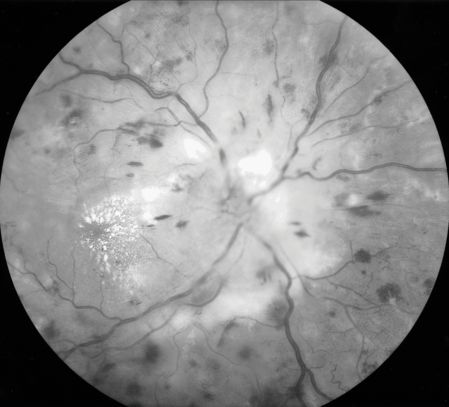

She was evaluated in ophthalmology where she was found to have visual acuity of 20/100 in the right eye and 20/100 in the left eye with bilateral optic disk edema, macular edema and exudates and blot hemorrhages (Figure 5.4).

Fundus photography of the right eye shows severe disc edema with prominent macular exudates, areas of retinal whitening and a combination of flame-shaped and dot-blot hemorrhages scattered throughout the posterior pole.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree