Sagittal T2 MRI cervical and thoracic spine showing multifocal T2 hyperintense lesions within the cervical and thoracic spinal cord compatible with multiple sclerosis.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: Lhermitte symptom, gait ataxia with resolution, recurrent inflammatory myelopathy, recurrent optic neuritis

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: brain MRI consistent with MS; spinal cord MRI consistent with MS; CSF consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis with nicotine dependence.

Tip: It is critical to initiate immunomodulatory medications for patients with relapsing-remitting disease, particularly those with frequent relapses after onset of the disease as well as those who develop new MRI lesions early on. Such patients are more likely to have more significant and more frequent attacks. In addition to this, it is imperative that these patients be encouraged to discontinue smoking immediately and offered the best medical assistance to do this. Patients who smoke cigarettes have difficulty controlling relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and have more challenging clinical courses according to most of the literature published on this question.

In this patient, despite the JC virus antibody positivity, it was considered that natalizumab still would be a possibility if its use was limited to 18 to 24 months, while the risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is relatively low. Consideration of alternative immunomodulatory medications including interferons, fingolimod or dimethyl fumarate was also apt for this patient. He was directed to a nicotine-dependence clinic for nicotine cessation, which will be an important adjunct in his MS therapy.

Case 19: A patient with continued relapses that is unresponsive to glatiramer acetate. Should she switch medications?

A 25-year-old woman awoke with binocular, painless, vertical and skewed diplopia that was worse on rightward gaze but which resolved spontaneously after a few weeks. Initially, an ophthalmologist diagnosed her with trochlear nerve palsy. On further consideration of her history, a Lhermitte symptom was identified earlier in the year of presentation. She had not had other symptoms that would suggest clinical features of attacks of multiple sclerosis apart from this. A paternal aunt was known to have multiple sclerosis, as was a distant maternal cousin. She was started on glatiramer acetate. She then had episodes consistent with three acute attacks of multiple sclerosis, including symptoms of an ascending cervical myelopathy, left-sided optic neuritis, and recurrent lower extremity numbness. She had been tolerating the glatiramer acetate well and had been adherent to it.

Her neurological examination was normal.

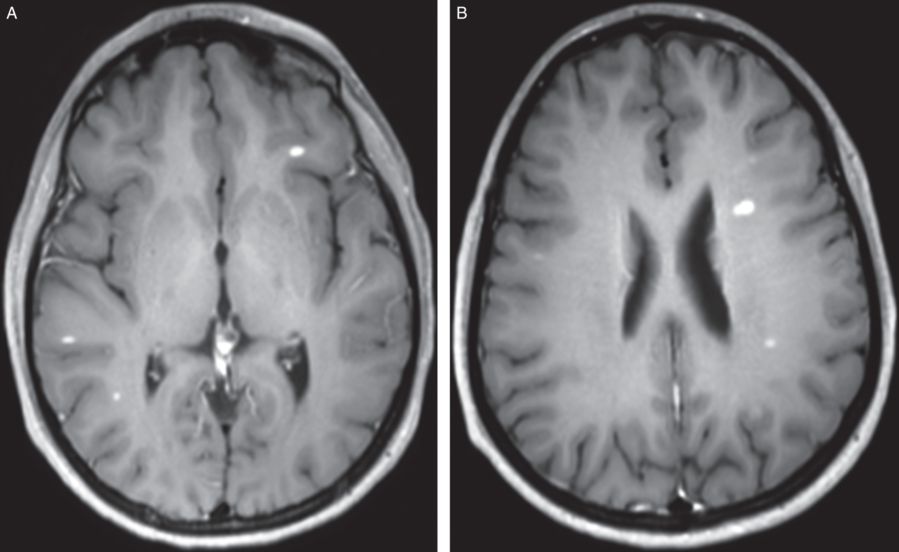

An initial brain MRI showed multiple areas of abnormal T2 signal, and one with gadolinium enhancement, consistent with multiple sclerosis. A repeat brain MRI showed an ongoing, active inflammatory component of her multiple sclerosis with many new gadolinium-enhancing lesions (Figure 4.2).

Axial T1 with gadolinium MRI brain showing substantial progression of multifocal contrast-enhancing lesions in the brain indicating incomplete control of the inflammatory component of MS.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: painless binocular, diplopia recurrent inflammatory myelopathy, optic neuritis

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: Brain MRI consistent with MS with activity

Diagnosis: Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis with activity, incomplete control of inflammation with glatiramer acetate.

The patient was switched to interferon beta 1a subcutaneously three times weekly. A repeat evaluation was performed. She had no new symptoms of clinical attacks over the next two years. Her neurological examination remained normal.

Tip: The two main indicators for switching MS therapies are tolerability and efficacy. This patient was adherent and tolerating glatiramer acetate but she continued to display ongoing clinical and radiological evidence of inflammation indicating incomplete efficacy. Clinicians must gauge the effectiveness of immunomodulatory medications of multiple sclerosis by estimating the prior and current relapse rate as well as new inflammatory MRI activity, and should change immunomodulatory medications to reassess new effectiveness.

Case 20: An MS patient intolerant of injections with bradycardia. What MS medications should be considered?

A 36-year-old gentleman was evaluated because of a history of right-sided foot dragging. Two months later it involved the right arm as well. He had not had prior episodes of clinical attacks and there was no family history of multiple sclerosis. He spontaneously improved, recovering to about 80 percent of normalcy without the use of steroids. The diagnosis was of a clinically isolated demyelination syndrome with a brainstem lesion. Multiple MRI MS lesions were found that put him at a high risk of developing relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. He initiated treatment with interferon beta 1a three times weekly but developed significant injection reaction pain so it was discontinued. The desire was to switch to an oral medication and fingolimod was identified as a major consideration. An electrocardiogram was done, which showed bradycardia at 46 beats per minute. His neurological examination was entirely normal.

A brain MRI scan showed areas of abnormal signal within the brainstem consistent with multiple sclerosis. A cervical spinal cord MRI showed T2 signal abnormality consistent with MS.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: brainstem attack; resolved hemiparesis

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: brain MRI consistent with MS; spinal cord MRI consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis with injection intolerance.

Tip: The presented patient had therapeutic intolerance mainly related to injections. This would lessen the consideration of using other injectable medications such as other interferon preparations or glatiramer acetate. Fingolimod, generally speaking, should not be a strong consideration because of the significant bradycardia present. Bradycardia is worsened by the use of fingolimod, particularly the first dose due to its effects on sphingosine 1 –phosphate (S1P) receptors on the cardiac atrial muscle. First-dose monitoring for bradycardia is recommended in all patients initiating treatment with fingolimod. Alternative oral MS therapies to be considered would be dimethyl fumarate or teriflunomide.

Case 21: A woman with MS previously treated with natalizumab. Should natalizumab be reinitiated after progression on interferon therapy?

A 53-year-old woman presented for evaluation of treatment recommendations for multiple sclerosis. Approximately 21 years earlier she had symptoms of a sensory myelopathy that resolved with corticosteroids. She recalled having symptoms later that year of bilateral upper extremity numbness as well as right-sided optic neuritis, which did not improve. Her sister, cousin, and great aunt all had multiple sclerosis. She was initiated on interferon beta 1b every other day subcutaneously from 1995 for the next five years. She then changed to interferon beta 1a intramuscularly once weekly for the next 11 years.

She described a progressive impairment in her gait over the last 13 years. The patient required the use of a cane for the last 18 months. It was not clear that there had been any new definite clinical attacks or relapses in a number of years. She had worsened arm weakness after stress only. Because of the continued progressive worsening, she was changed to natalizumab one and a half years prior to being seen. She had received 15 infusions in total. The most recent evaluation for JC virus antibodies was six months prior to evaluation, and it remained negative.

On neurological examination, her mental status was found to be normal. She had mild weakness distally in the upper extremities and moderate weakness in a pyramidal distribution greater in the left than right lower extremity. She walked with a bilateral circumductive ataxic gait, and plantar responses were extensor bilaterally.

Repeat brain MRI scans revealed no new T2 lesions and no new gadolinium-enhancing lesions over many years of serial imaging. Repeat cervical and thoracic spine MRIs showed multiple chronic areas of demyelinating disease, again without evidence of new active demyelination or gadolinium enhancement. A JC virus serum antibody test was repeated and was now positive consistent with recent seroconversion.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: progressive quadriparetic gait disorder, optic neuritis; prior sensory myelopathy with resolution

2 Neurological examination: consistent with myelopathy

3 Investigations: brain MRI consistent with MS; spinal cord MRI consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Tip: Check clinical history and imaging findings as well as old MRI reports to gauge whether there has been clear, new inflammatory activity consistent with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. If not, most immunomodulatory medications should not be strongly considered.

Given that this patient’s gait had worsened over the last ten years and she had a 22-year disease course, it was suggestive that she has secondary progressive multiple sclerosis rather than a relapsing inflammatory component.

Repeat serological testing for JC virus-negative patients should take place approximately every six months to assess for seroconversion. In this patient, consideration was not made for natalizumab given the secondary progressive course. In addition to that, she is now JC virus antibody positive, which would put her at risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

Case 22: Episodic symptomatic worsening in a patient with MS. Should highly aggressive immunomodulatory therapy be recommended?

A 62-year-old woman came for assessment. Her symptom onset began approximately three decades earlier. She had relapsing symptoms of vertigo or upper extremity weakness and numbness, always with resolution. Despite the onset and symptoms, she was evaluated formally for this only three years prior to evaluation. She recalls walking three or four miles a day dating back to five years prior to evaluation. She then started to require unilateral gait assistance three years prior to evaluation and started to use bilateral ski poles for one year prior to evaluation. A paternal aunt was known to have multiple sclerosis, and a sister had optic neuritis.

She initially was treated with glatiramer acetate but suffered from side effects. She was then started on dimethyl fumarate. She was hospitalized on four or five occasions prior to evaluation. She had symptomatic worsening: once with an influenza vaccination, once with a colonoscopy and once with angina pectoris. The patient reported that after the hospitalizations, she was essentially wheelchair bound but had recovered enough so that she could walk on occasion with her ski poles for about one block only.

She had no new symptoms of spontaneous clinical attacks of multiple sclerosis such as optic neuritis, new-onset diplopia, dysarthria, hemiparesis or hemisensory deficit.

On neurological examination she had a moderate upper motor neuron pattern quadriparesis with spasticity and a right greater than left circumductive gait impairment. Plantar response was extensor on the right and flexor on the left. She had vibratory sensory loss in the feet bilaterally.

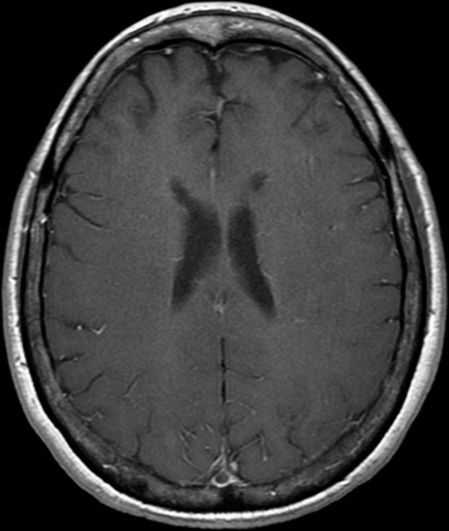

Serial brain and spinal cord MRI scans showed no evidence of new inflammatory multiple sclerosis lesions even during times of symptomatic worsening (Figure 4.3).

Axial T1 MRI brain showing an ovoid chronic and inactive area of T1 hypointensity (“black hole”) consistent with chronic MS. Cervical and thoracic spine MRIs showed multifocal, non-enhancing T2 hyperintense lesions (not shown). Pseudoexacerbations are common in patients with progressive forms of MS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree