Charcot and Psychogenic Movement Disorders

Christopher G. Goetz

ABSTRACT

In his neurologic unit at the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot studied many patients who today would likely be considered to have psychogenic movement disorders. Collectively diagnosed primarily under the designation hysteria, these patients had a variety of focal neurologic signs, sometimes static and sometimes fleeting. Tremors, dystonic postures, chorea, stereotypes, and complex, often bizarre, contortions were among the phenomena. Although Charcot’s intense interest in hysteria has prompted some historians to label him incorrectly as a psychiatrist, his views remained entrenched in neuroanatomy and he never considered psychological stress as the primary cause of neurologic signs. His study methods and interpretation of hysteria were controversial and led to his serious loss of scientific credibility in the closing years of his career. Although these studies are largely forgotten, as the modern field of psychogenic neurology emerges as a new research arena, Charcot’s controversial work on hysteria requires review as a primary historical foundation for contemporary work. Although many of the criticisms of Charcot’s work on hysteria are justified, a reconsideration of primary source documents from his lectures, case histories, and notes emphasizes Charcot’s views on anatomic, hereditary, and physiologic issues that reemerge in the modern study of psychogenic movement disorders.

INTRODUCTION

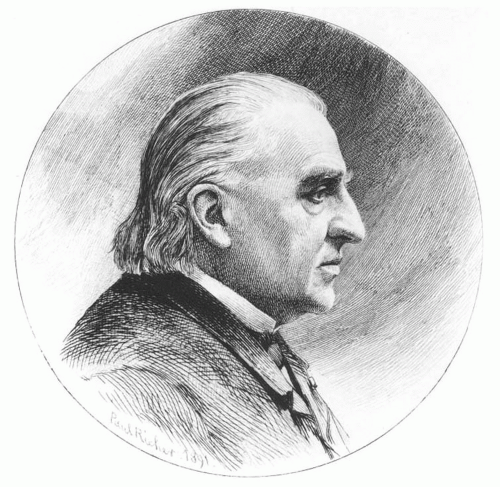

Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) was the premier clinical neurologist of the 19th century (Fig. 1.1). Working in Paris at the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, he converted the walled hospice-city into a world-famous neurologic service. He drew colleagues and students from around the world to study with him and to attend his lectures and classroom demonstrations. Studying with Charcot provided younger colleagues with the credentials to develop neurologic careers and return to their native cities or countries as neurological specialists (1).

Although Charcot contributed to many areas of neurology and medicine, his most important areas of research focused on three issues: the development of a nosology or classification system for neurology (2,3); the practical application of the anatomoclinical method whereby he correlated for the first time specific clinical neurologic signs with focal anatomic lesions (4); and, finally, the study of the neurologic disorder hysteria (5).

Modern readers may consider the topic of hysteria to be outside the realm of neurology and more suitable to the research career of a psychiatrist. In the 19th century, however, hysteria was a specific and, largely due to Charcot’s work, well-defined neurologic diagnosis. Psychiatry dealt primarily with diseases causing insanity,

and during this period French neurology and psychiatry were completely separate specialties (6). Neurology was linked to internal medicine, and in Charcot’s case most specifically to geriatric medicine. In studying hysteria, Charcot approached the disorder categorically as a neurologist, firmly bound to the growing knowledge of neuroanatomy and without links to or active interactions with psychiatrists of his day. A member of many medical societies and groups that crossed the interface of neurology and allied fields, Charcot was never a member of any psychiatric association (1).

and during this period French neurology and psychiatry were completely separate specialties (6). Neurology was linked to internal medicine, and in Charcot’s case most specifically to geriatric medicine. In studying hysteria, Charcot approached the disorder categorically as a neurologist, firmly bound to the growing knowledge of neuroanatomy and without links to or active interactions with psychiatrists of his day. A member of many medical societies and groups that crossed the interface of neurology and allied fields, Charcot was never a member of any psychiatric association (1).

Figure 1.1 Jean-Martin Charcot. Engraving by P. Richer, 1892. (From Goetz CG. Charcot, the clinician: the Tuesday lessons. New York: Raven Press, 1987.) |

The topic of this volume, psychogenic movement disorders emphasizes an interface between neurology and psychiatry that Charcot never knew. Indeed, he dealt with the gamut of movement disorders, making pivotal observations that affect the history of Parkinson disease, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, Huntington disease, dystonia, and tremors, but he worked exclusively within the context of neuroanatomy (2). Within Charcot’s extensive work on hysteria, the modern movement disorder specialist will find cases that likely fit the current designation of psychogenic movement disorders. Nonetheless, in examining these entities within a very strictly neurologic context without a psychiatric focus, it is very reasonable to ask if Charcot can be legitimately viewed as a key figure in the study of this diagnostic domain. Is Charcot an appropriate starting point historically for an up-to-date consideration of psychogenic movement disorders?

This chapter will argue that Charcot contributed indirectly to the modern understanding of the topic of psychogenic movement disorders and provided a number of pertinent observations and experimental approaches for studying patients who fit this diagnostic category. But throughout his career, in his nosologic analysis, anatomoclinical approach, and specific studies of hysteria, Charcot never dealt directly with the concept of psychological stress as a primary cause of neurologic diseases. To trace Charcot’s contributions to psychogenic movement disorders, this chapter will examine Charcot’s views on movement disorders as a nosologic classification, his concept of disease etiology, and the diagnosis of hysteria. With this background, the chapter will then explore Charcot’s observations and conclusions on the role of suggestion, by self and outside persons, on neurologic function, specifically with reference to movement disorders. These analyses will help to place the topic of psychogenic movement disorders in the historical context of Charcot’s contributions and provide a framework for the modern data and experimental approaches discussed in the remaining chapters of this volume.

MOVEMENT DISORDERS IN THE CHARCOT NOSOLOGY: THE NÉVROSES

Prior to Charcot, most neurologic disorders were described by large categories of symptoms and not by anatomical lesions. Motor disorders included weakness, spasms, and palsies. Multiple sclerosis and Parkinson disease were not differentiated, and cases with either diagnosis were coalesced because they both were marked by tremor. Charcot’s clinical skills, discipline of a systematic method of examination, and large patient population allowed him to refine clinical categories, defining several disorders with both archetypal presentations as well as variants or formes frustes (1). With this clinical analysis, Charcot published the first major description of Parkinson disease (7), supervised the seminal article by Gilles de la Tourette on tic disorders (8), and wrote on chorea (9) and various forms of focal dystonia, termed occupational spasms (10). These reports remain neurologic anchors of clinical description, even in the 21st century.

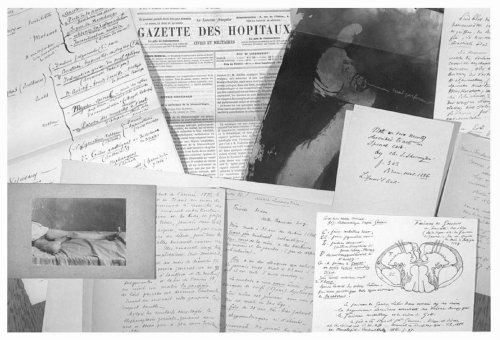

The leitmotif of Charcot’s approach was termed the “anatomoclinical method” or méthode anatomoclinique. On the basis of the model originally applied by Laennec, Charcot sought to identify the anatomical basis of neurological symptoms (4). In this two-part discipline, the first step involved the examination of thousands of patients and a careful description of their neurologic signs. Taking advantage of the vast population within the Salpêtrière wards, he culled the medical service to categorize patients by the signs they demonstrated and studied them to document symptom evolution over time. His hand-written notes and sketches of patients were kept in large patient files that can still be examined at the Bibliothèque Charcot within the modern Salpêtrière complex (Fig. 1.2).

The second phase of the anatomoclinical method involved autopsy examinations. Because the Salpêtrière patients were wards of the state, when they died Charcot likely had automatic access to nervous system tissue. He developed a sophisticated neuropathology service and focused his postmortem studies on a systematic process that cross-referenced identified lesions to the clinical signs experienced during life. Charcot’s crowning anatomoclinical research concerned the identification of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, internationally still widely known as Charcot’s disease. He demonstrated that spasticity and pseudobulbar effect related to upper motor neuron lesions of the lateral columns, whereas atrophy and fasciculations occurred in the body regions associated with anterior horn cell loss (11). Comparable anatomoclinical studies illuminated the pathologic basis of locomotor ataxia, myelopathies, and some of the early aphasia syndromes.

As dramatic as these discoveries were, the second phase of study was not always revealing. Numerous entities, including several movement disorders, Parkinson disease, choreas, tics, and dystonic spasms, were not associated with anatomic lesions that Charcot could identify. Charcot established a new category of neurologic disorders, the névroses or neuroses, to classify the numerous neurologic conditions that were well-characterized clinically but still had no identifiable lesion (3). The term neurosis in English today applies to psychiatric conditions, although this newer usage dates to the 20th century. Because of the ambiguity of the English term, névrose will be used throughout this discussion. This category of névroses was intentionally tentative, as Charcot anticipated that future studies would identify the responsible structural lesions.

Other diagnoses that fell under the category of the névroses included paroxysmal disorders like epilepsies, migraines, and hysteria. In contrast to the névroses with static signs that Charcot believed could eventually be explained with more precise autopsy analyses, he contended that paroxysmal névroses did not have static lesions but related to transient or, in his terms, “dynamic” changes in physiologic function within very specific neuroanatomic regions (12). He deduced the involved brain regions by drawing parallels between focal signs seen during these paroxysmal episodes and anatomoclinical discoveries he had previously made with disorders showing similar, but static, signs and clear anatomical lesions. The focal signs that occurred in the midst of a focal epileptic spell, migraine attack, or hysterical episode therefore related to involvement of the same neuroanatomic regions affected

in subjects with similar clinical signs due to strokes or abscesses. In this way, when he observed a focal seizure of the left hand with a residual postictal paresis, Charcot concluded that the right motor cortex of the precentral gyrus was transiently affected, since he had seen this same area lesioned with tumors or strokes in cases of static left hand weakness. As a natural extension to hysteria, another névrose, he concluded similarly, arguing that in hysteria the signs of transient hemiparesis, blindness, contorted postures, and other focal signs had a specific neuroanatomic basis.

in subjects with similar clinical signs due to strokes or abscesses. In this way, when he observed a focal seizure of the left hand with a residual postictal paresis, Charcot concluded that the right motor cortex of the precentral gyrus was transiently affected, since he had seen this same area lesioned with tumors or strokes in cases of static left hand weakness. As a natural extension to hysteria, another névrose, he concluded similarly, arguing that in hysteria the signs of transient hemiparesis, blindness, contorted postures, and other focal signs had a specific neuroanatomic basis.

CHARCOT AND THE CAUSE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASES

Charcot’s observational skills and dispassionate evaluation of neurologic signs led him to see himself as “a photographer,” and he was particularly conscious of the pitfalls of preconceived bias (10). Nonetheless, Charcot held to one primary preconception throughout his career and maintained that the underlying cause of all primary neurologic disease was hereditary (1). In his view, largely reflective of the 19th century as a whole, he adamantly held that patients with neurologic diseases inherited from prior generations a weakness, or tache, that predisposed them to neurologic disorders. Environmental factors, including cold, trauma, stress, and infections, influenced the underlying proclivity to disease and could provoke or exacerbate signs in affected subjects. The same environmental factors, however, would have no impact on subjects without the familial tache. Conversely, within a family with neurologic disease, the avoidance of unhealthy influences could protect subjects so that even with the hereditary condition some careful members could remain asymptomatic or only mildly affected (10).

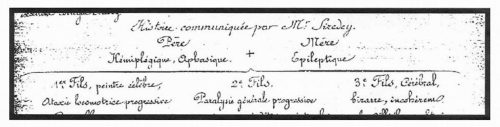

Charcot constructed extensive family trees in support of his premise and showed that most neurologically impaired patients had obvious or hidden family members with neurologic diseases as well. He emphasized, however, that the actual neurologic manifestations of disease varied among family members. In one genealogy (Fig. 1.3) (10) the parents were afflicted with aphasia, hemiplegia, and epilepsy, whereas the children revealed their neurologic disorder in the form of locomotor ataxia and general paresis (dissimilar inheritance). More rarely, the same manifestations of neurologic impairment passed between generations (similar inheritance). Within Charcot’s conceptual framework of the neuropathic family of diseases, disorders due to structural lesions and the névroses were equal in neurologic legitimacy, all being fundamentally hereditary and all intermingled within families.

Against this familial backdrop, the final clinical manifestations of the neurologic disorder depended largely on an array of environmental factors or agents provocateurs. For instance, in the case of locomotor ataxia or tabes dorsalis, Charcot held adamantly that syphilis was not the cause of the illness but was frequently associated with the disorder because syphilis weakened the body:

There are conditions that relate to diseases as provocative agents. Trauma can unveil almost any illness to which a person is already predisposed. Syphilis too is undoubtedly important, and if we see many ataxics who were once syphilitic, we can reasonably ask whether ataxia would have ever developed without prior syphilis. Without syphilis, the tabes will not develop at all clinically, or, if it does, it will come later (2,10).

In a similar context, he noted that children with Sydenham chorea often had added cardiac disease, the latter causing a generalized weakening of the body and allowing the clinical expression of hereditary chorea. Other environmental precipitants, both acute and chronic, included cold, shock, and humidity, all seen as provoking or exacerbating influences that potentially unleashed neurologic syndromes, including Parkinson disease, chorea, tics, epilepsy, and hysteria among hereditarily predisposed subjects (7,10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree