Child Psychiatry

31.1 Introduction: Infant, Child, and Adolescent Development

31.1 Introduction: Infant, Child, and Adolescent Development

The transactional nature of development in infancy, childhood, and adolescence, consisting of a continuous interplay between biological predisposition and environmental experiences, forms the basis of current conceptualizations of development. There is much evidence that observed developmental outcomes evolve from interactions between particular biological substrates and specific environmental events. For example, the serotonin transporter gene sensitizes a child with early adverse experiences of abuse or neglect to increased risk for later development of a depressive disorder. In addition, the degree of resilience and adaptation, that is, the ability to withstand adversity without negative effects, is likely to be mediated by endogenous glucocorticoids, cytokines, and neurotrophins. Thus, allostasis, the process of achieving stability in the face of adverse environmental events, results from interactions between specific environmental challenges and particular genetic backgrounds that combine to result in a response. It is widely accepted that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are likely to alter the trajectory of development in a given individual, and that during early development the brain is especially vulnerable to injury. Future studies may uncover windows of plasticity in older children and adolescents that affect vulnerability as well. Changes in both white matter and gray matter in the brains of adolescents are linked to increased acquisition of subtle social skills. Adolescents’ keen abilities, competencies, and interests in a host of technological advances—including the Internet, social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and smart phones, to name a few—shed some light on their potential to adapt to new and challenging demands.

PRENATAL, INFANT, AND CHILD

The phases of development described in this section are defined as follows: prenatal is the time frame from conception to 8 weeks; the fetus, from 8 weeks to birth; infancy, from birth to 15 months; the toddler period, from 15 months to 2½ years; the preschool period, from 2½ years to 6 years; and the middle years, from 6 to 12 years.

PRENATAL

Historically, the analysis of human development began with birth. The influence of endogenous and exogenous in utero factors, however, now requires that developmental schemes take intrauterine events into consideration. The infant is not a tabula rasa, a smooth slate upon which outside influences etch patterns. To the contrary, the newborn has already been influenced by myriad factors that have occurred in the safety of the womb, the result of which has produced wide individual differences among infants. For example, the studies of Stella Chess and Alexander Thomas (described later) have demonstrated a wide range of temperamental differences among newborns. Maternal stress, through the production of adrenal hormones, also influences behavioral characteristics of newborns.

The time frame in which the development of the embryo and fetus occurs is known as the prenatal period. After implantation, the egg begins to divide and is known as an embryo. Growth and development occur at a rapid pace; by the end of 8 weeks, the shape is recognizably human, and the embryo has become a fetus. Figure 31.1-1 illustrates a sonogram of a 9-week and 15-week fetus in utero.

FIGURE 31.1-1

A. Sonogram of fetus at 9 weeks. B. Same fetus at 15 weeks. (Courtesy K.C. Attwell, M.D.)

The fetus maintains an internal equilibrium that, with variable effects, interacts continuously with the intrauterine environment. In general, most disorders that occur are multifactorial—the result of a combination of effects, some of which can be additive. Damage at the fetal stage usually has a more global impact than damage after birth, because rapidly growing organs are the most vulnerable. Boys are more vulnerable to developmental damage than girls are; geneticists recognize that in humans and animals, female fetuses show a propensity for greater biological vigor than male fetuses, possibly because of the second X chromosome in the female.

Prenatal Life

Much biological activity occurs in utero. A fetus is involved in a variety of behaviors that are necessary for adaptation outside the womb. For example, a fetus sucks on thumb and fingers; folds and unfolds its body, and eventually assumes a position in which its occiput is in an anterior vertex position, which is the position in which fetuses usually exit the uterus.

Behavior. Pregnant women are extraordinarily sensitive to prenatal movements. They describe their unborn babies as active or passive, as kicking vigorously or rolling around, as quiet when the mothers are active, but as kicking as soon as the mothers try to rest.

Women usually detect fetal movements 16 to 20 weeks into the pregnancy; the fetus can be artificially set into total body motion by in utero stimulation of its ventral skin surfaces by the 14th week. The fetus may be able to hear by the 18th week, and it responds to loud noises with muscle contractions, movements, and an increased heart rate. Bright light flashed on the abdominal wall of the 20-week pregnant woman causes changes in fetal heart rate and position. The retinal structures begin to function at that time. Eyelids open at 7 months. Smell and taste are also developed at this time, and the fetus responds to substances that may be injected into the amniotic sac, such as contrast medium. Some reflexes present at birth exist in utero: the grasp reflex, which appears at 17 weeks; the Moro (startle) reflex, which appears at 25 weeks; and the sucking reflex, which appears at about 28 weeks.

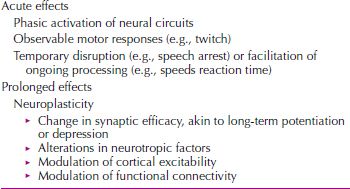

Nervous System. The nervous system arises from the neural plate, which is a dorsal ectodermal thickening that appears on about day 16 of gestation. By the sixth week, part of the neural tube becomes the cerebral vesicle, which later becomes the cerebral hemispheres (Fig. 31.1-2).

FIGURE 31.1-2

Formation of the neural tube and neural crest. These schematic illustrations follow the early development of the nervous system in the embryo. The drawings above are dorsal views of the embryo; those below are cross sections. A. The primitive embryonic central nervous system (CNS) begins as a thin sheet of ectoderm. B. The first important step in the development of the nervous system is the formation of the neural groove. C. The walls of the groove, called neural folds, come together and fuse, forming the neural tube. D. The bits of neural ectoderm that are pinched off when the tube rolls up are called the neural crest, from which the peripheral nervous system (PNS) will develop. The somites are mesoderm that will give rise to much of the skeletal system and the muscles. (Reprinted from Bear MF, Conners BW, Paradiso MA, eds. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001:179, with permission.)

The cerebral cortex begins to develop by the 10th week, but layers do not appear until the sixth month of pregnancy; the sensory cortex and the motor cortex are formed before the association cortex. Some brain function has been detected in utero by fetal encephalographic responses to sound. The human brain weighs about 350 g at birth and 1,450 g at full adult development, a fourfold increase, mainly in the neocortex. This increase is almost entirely because of the growth in the number and branching of dendrites establishing new connections. After birth, the number of new neurons is negligible. Uterine contractions can contribute to fetal neural development by causing the developing neural network to receive and transmit sensory impulses.

Pruning

Pruning refers to the programmed elimination during development of neurons, synapses, axons, and other brain structures from the original number, present at birth, to a lesser number. Thus, the developing brain contains structures and cellular elements that are absent in the older brain. The fetal brain generates more neurons than it will need for adult life. For example, in the visual cortex, neurons increase in number from birth to 3 years of age, at which point they diminish in number. Another example is that the adult brain contains fewer neural connections than were present during the early and middle years of childhood. Approximately twice as many synapses are present in certain parts of the cerebral cortex during early postnatal life than during adulthood.

Pruning occurs to rid the nervous system of cells that have served their function in the development of the brain. Some neurons, for example, exist to produce neurotrophic or growth factors and are programmed to die—a process called apoptosis—when that function is fulfilled.

The implication of these observations is that the immature brain can be vulnerable in locations that lack sensitivity to injury later on. The developing white matter of the human brain before 32 weeks of gestation is especially sensitive to damage from hypoxic and ischemic injury and metabolic insults. Neurotransmitter receptors located on synaptic terminals are subject to injury from excessive stimulation by excitatory amino acids, (e.g., glutamate, aspartate), a process referred to as excitotoxicity. Research is proceeding on the implications of such events in the etiology of child and adult neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.

Maternal Stress

Maternal stress correlates with high levels of stress hormones (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and adrenocorticotropic hormone) in the fetal bloodstream, which act directly on the fetal neuronal network to increase blood pressure, heart rate, and activity level. Mothers with high levels of anxiety are more likely to have babies who are hyperactive, irritable, and of low birth weight, and who have problems feeding and sleeping than are mothers with low anxiety levels. A fever in the mother causes the fetus’s temperature to rise.

Genetic Disorders

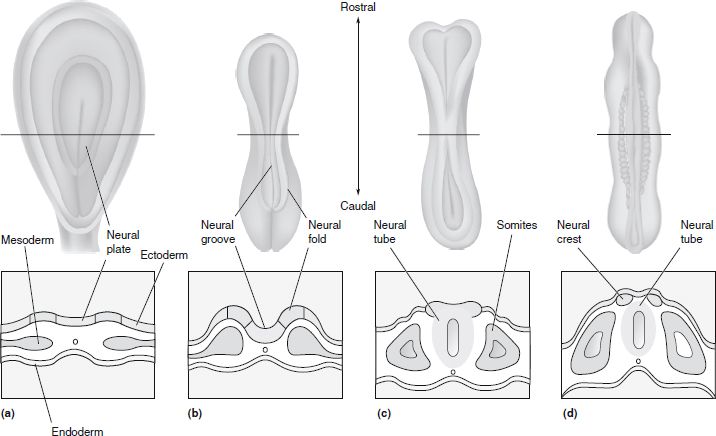

In many cases, genetic counseling depends on prenatal diagnosis. The diagnostic techniques used include amniocentesis (transabdominal aspiration of fluid from the amniotic sac), ultrasound examinations, x-ray studies, fetoscopy (direct visualization of the fetus), fetal blood and skin sampling, chorionic villus sampling, and α-fetoprotein screening. In about 2 percent of women tested, the results are positive for some abnormality, including X-linked disorders, neural tube defects (detected by high levels of α-fetoprotein), chromosomal disorders (e.g., trisomy 21), and various inborn errors of metabolism (e.g., Tay-Sachs disease and lipoidoses). Figure 31.1-3 illustrates hypertelorism of the eyes.

FIGURE 31.1-3

Hypertelorism. Note the wide distance between the eyes, flat nasal bridge, and external strabismus. (Courtesy of Michael Malone, M.D. Children’s Hospital, Washington, D.C.)

Some diagnostic tests carry a risk; for instance, about 5 percent of women who undergo fetoscopy miscarry. Amniocentesis, which is usually performed between the 14th and 16th weeks of pregnancy, causes fetal damage or miscarriage in less than 1 percent of women tested. Fully 98 percent of all prenatal tests in pregnant women reveal no abnormality in the fetus. Prenatal testing is recommended for women older than 35 years of age and for those with a family history of a congenital defect.

Parental reactions to birth defects can include feelings of guilt, anxiety, or anger as their worst fears during the pregnancy are realized. Some degree of depression over the loss of the fantasized perfect child may be observed before the parents develop more active coping strategies. Termination of a pregnancy because of a known or suspected birth defect is an option chosen by some women.

Maternal Drug Use

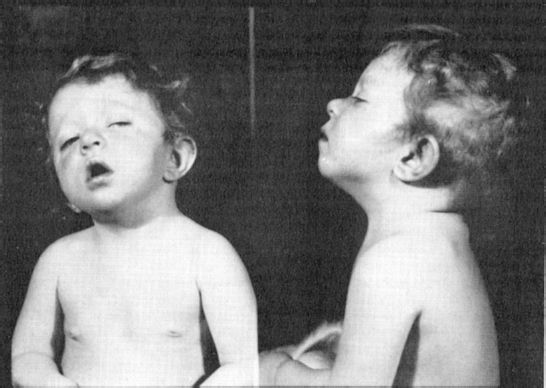

Alcohol. Alcohol use in pregnancy is a major cause of serious physical and mental birth defects in children. Each year, up to 40,000 babies are born with some degree of alcohol-related damage. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports that 19 percent of pregnant women used alcohol during their pregnancy, the highest rate being among white women.

Fetal alcohol syndrome (Fig. 31.1-4) affects about one third of all infants born to alcoholic women. The syndrome is characterized by growth retardation of prenatal origin (height, weight); minor anomalies, including microphthalmia (small eyeballs), short palpebral fissures, midface hypoplasia (underdevelopment), a smooth or short philtrum, and a thin upper lip; and central nervous system (CNS) manifestations, including microcephaly (head circumference below the third percentile), a history of delayed development, hyperactivity, attention deficits, learning disabilities, intellectual deficits, and seizures. The incidence of infants born with fetal alcohol syndrome is about 0.5 per 1,000 live births.

FIGURE 31.1-4

Photographs of children with “fetal-alcohol syndrome.” A. Severe case. B. Slightly affected child. Note in both children the short palpebral fissures and hypoplasia of the maxilla. Usually, the defect includes other craniofacial abnormalities. Cardiovascular defects and limb deformities are also common symptoms of the fetal alcohol syndrome. (From Langman J. Medical Embryology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:108, with permission.)

Some studies suggest that alcohol use during pregnancy may contribute to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Animal experiments have shown that alcohol reduces the number of active dopamine neurons in the midbrain area, and ADHD is associated with reduced dopaminergic activity in the brain.

Smoking. Smoking during pregnancy is associated with both premature births and below-average infant birth weight. Some reports have associated sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) with mothers who smoke.

Other Substances. Marijuana (used by 3 percent of all pregnant women) and cocaine (used by 1 percent) are the two most commonly abused illegal drugs, followed by heroin. Chronic marijuana use is associated with low infant birth weight, prematurity, and withdrawal-like symptoms, including excessive crying, tremors, and hyperemesis (severe and chronic vomiting). Crack cocaine use by women during pregnancy has been correlated with behavioral abnormalities such as increased irritability and crying and decreased desire for human contact. Infants born to mothers dependent on narcotics go through a withdrawal syndrome at birth.

Prenatal exposure to various prescribed medications can also result in abnormalities. Common drugs with teratogenic effects include antibiotics (tetracyclines), anticonvulsants (valproate [Depakene], carbamazepine [Tegretol], phenytoin [Dilantin]), progesterone-estrogens, lithium (Eskalith), and warfarin (Coumadin). Table 31.1-1 outlines the etiologies of malformations that may emerge during the first year of life.

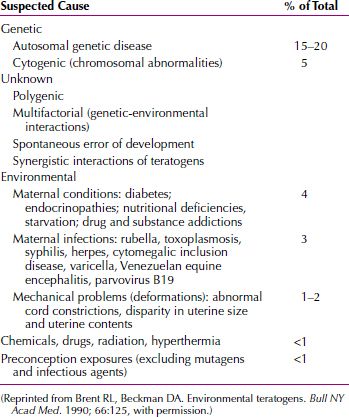

Table 31.1-1

Table 31.1-1

Causes of Human Malformations Observed During the First Year of Life

INFANCY

The delivery of the fetus marks the start of infancy. The average newborn weighs about 3,400 g (7.5 lb.). Small fetuses, defined as those with a birth weight below the 10th percentile for their gestational age, occur in about 7 percent of all pregnancies. At the 26th to the 28th week of gestation, the prematurely born fetus has a good chance of survival. Arnold Gesell described developmental landmarks that are widely used in both pediatrics and child psychiatry. These landmarks outline the sequence of children’s motor, adaptive, and personal–social behavior from birth to 6 years (Table 31.1-2).

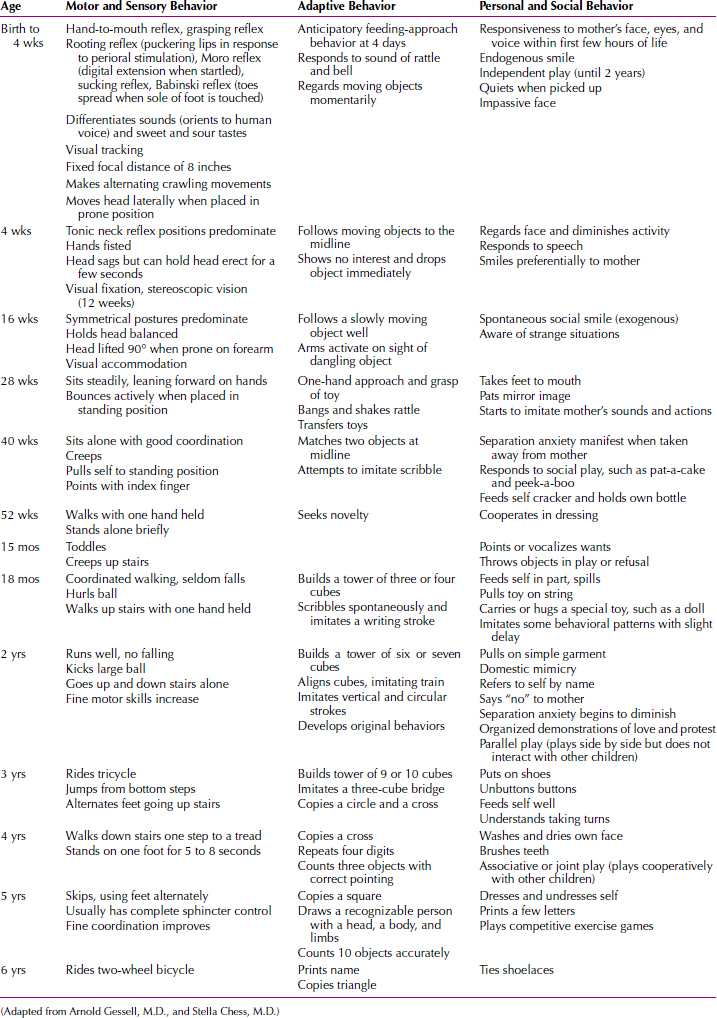

Table 31.1-2

Table 31.1-2

Landmarks of Normal Behavioral Development

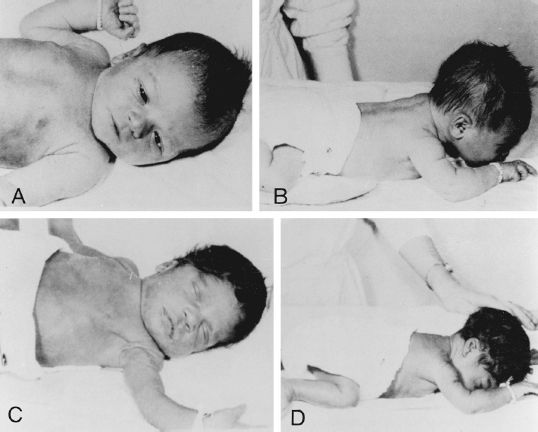

Premature infants are defined as those with a gestation of less than 34 weeks or a birth weight less than 2,500 g (5.5 lb.). Such infants are at increased risk for learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, emotional and behavioral problems, mental retardation, and child abuse. With each 100 g increment of weight, beginning at about 1,000 g (2.2 lb.), infants have a progressively better chance of survival. A 36-week-old fetus has less chance of survival than a 3,000 g (6.6 lb) fetus born close to term. The differences between full-term and infants born prematurely are shown in Figure 31.1-5.

FIGURE 31.1-5

Contrast between full-term (A and B) and premature (C and D) infants. Note the limp sprawl of the baby in C and the difficulty in raising the head to clear the nose and mouth in D. (Reprinted from Stone LJ, Church J. Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. New York: Random House; 1979:7, with permission.)

Postmature infants are defined as infants born 2 weeks or more beyond the expected date of birth. Because pregnancy at term is calculated as extending 40 weeks from the last menstrual period and the exact time of fertilization varies, the incidence of postmaturity is high if based on menstrual history alone. The postmature baby typically has long nails, scanty lanugo, more scalp hair than usual, and increased alertness.

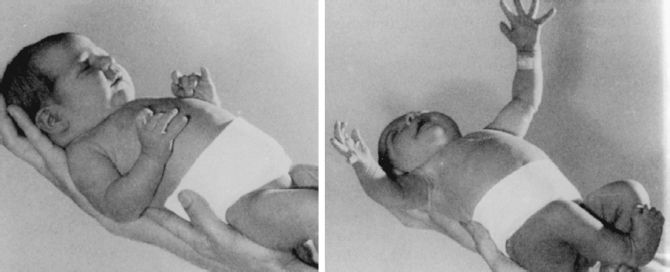

Developmental Milestones in Infants

Reflexes and Survival Systems at Birth. Reflexes are present at birth. They include the rooting reflex (puckering of the lips in response to perioral stimulation), the grasp reflex, the plantar (Babinski) reflex, the knee reflex, the abdominal reflexes, the startle (Moro) reflex (Fig. 31.1-6), and the tonic neck reflex. In normal children, the grasp reflex, the startle reflex, and the tonic neck reflex disappear by the fourth month. The Babinski reflex usually disappears by the 12th month.

FIGURE 31.1-6

Moro reflex. (Reprinted with permission from Stone LJ, Church J. Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. New York: Random House 1979:14 with permission.)

Survival systems—breathing, sucking, swallowing, and circulatory and temperature homeostasis—are relatively functional at birth, but the sensory organs are incompletely developed. Further differentiation of neurophysiological functions depends on an active process of stimulatory reinforcement from the external environment, such as persons touching and stroking the infant. The newborn infant is awake for only a short period each day; rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep are present at birth. Other spontaneous behaviors include crying, smiling, and penile erection in males. Infants 1 day old can detect the smell of their mother’s milk, and those 3 days old distinguish their mother’s voice.

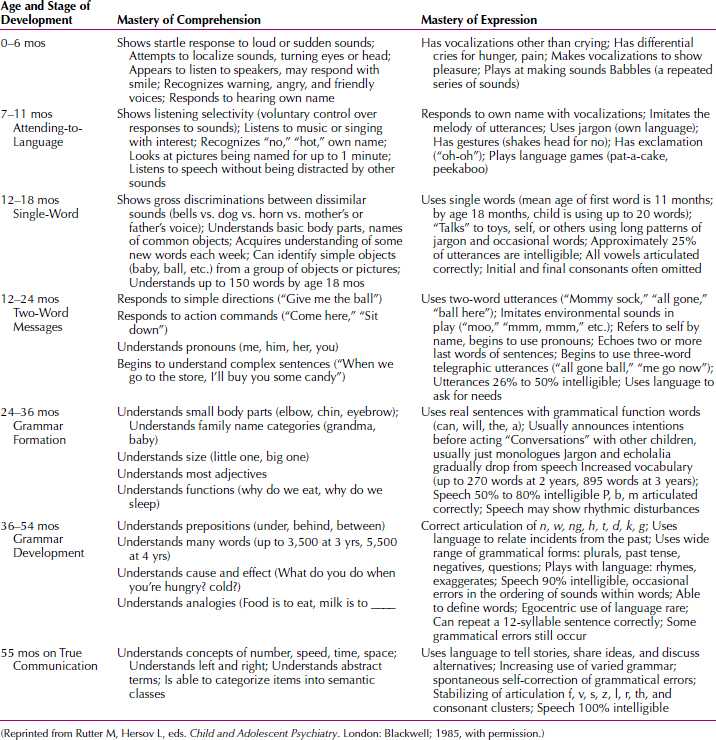

Language and Cognitive Development. At birth, infants can make noises, such as crying, but they do not vocalize until about 8 weeks. At that time, guttural or babbling sounds occur spontaneously, especially in response to the mother. The persistence and further evolution of children’s vocalizations depend on parental reinforcement. Language development occurs in well-delineated stages as outlined in Table 31.1-3.

Table 31.1-3

Table 31.1-3

Language Development

By the end of infancy (about 2 years), infants have transformed reflexes into voluntary actions that are the building blocks of cognition. They begin to interact with the environment, to experience feedback from their own bodies, and to become intentional in their actions. By the end of the second year of life, children begin to use symbolic play and language.

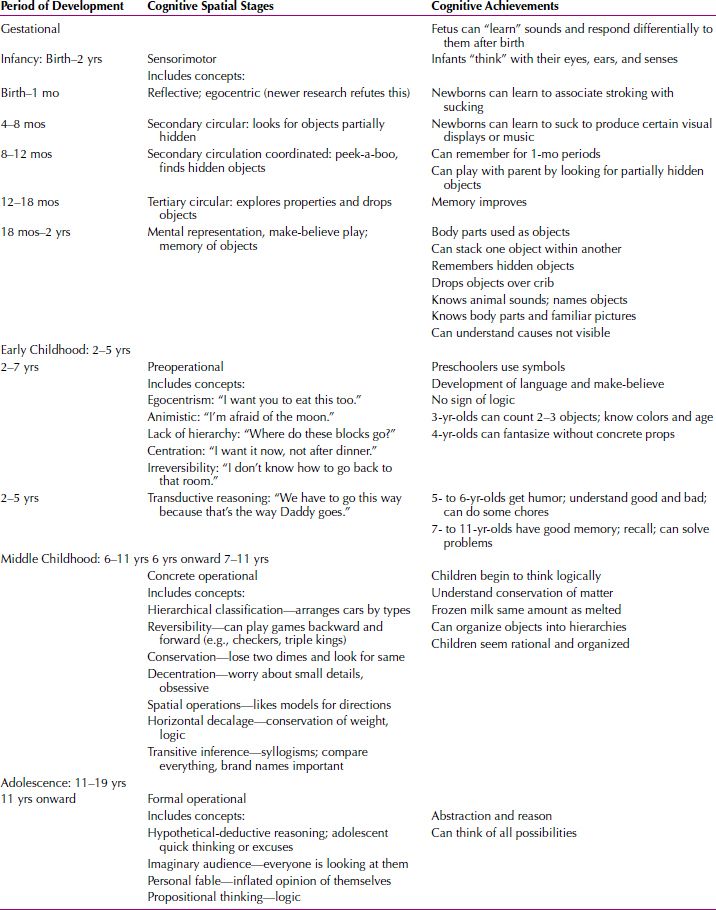

Jean Piaget (1896–1980), a Swiss psychologist, observed the growing capacity of young children (including his own) to think and to reason. An outline of the Piaget’s stages of cognitive development is presented in Table 31.1-4.

Table 31.1-4

Table 31.1-4

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

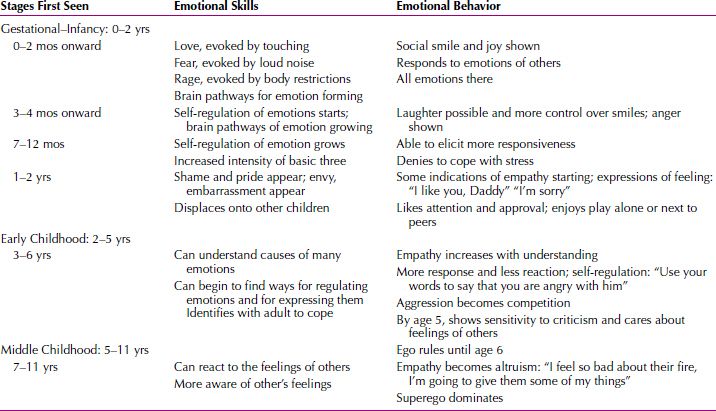

Emotional and Social Development. By the age of 3 weeks, infants imitate the facial movements of adult caregivers. They open their mouths and thrust out their tongues in response to adults who do the same. By the third and fourth months of life, these behaviors are easily elicited. These imitative behaviors are believed to be the precursors of the infant’s emotional life. The smiling response occurs in two phases: the first phase is endogenous smiling, which occurs spontaneously within the first 2 months and is unrelated to external stimulation; the second phase is exogenous smiling, which is stimulated from the outside, usually by the mother, and occurs by the 16th week.

The stages of emotional development parallel those of cognitive development. Indeed, the caregiving person provides the major stimulus for both aspects of mental growth. Human infants depend totally on adults for survival. Through warm and predictable interactions, an infant’s social and emotional repertoire expands with the interplay of caregivers’ social responses (Table 31.1-5).

Table 31.1-5

Table 31.1-5

Emotional Development

In the first year, infants’ moods are highly variable and intimately related to internal states such as hunger. Toward the second two thirds of the first year, infants’ moods grow increasingly related to external social cues; a parent can get even a hungry infant to smile. When the infant is internally comfortable, a sense of interest and pleasure in the world and in its primary caregivers should prevail. Prolonged separation from the mother (or other primary caregiver) during the second 6 months of life can lead to depression that may persist into adulthood as part of an individual’s character.

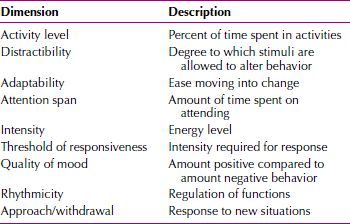

Temperamental Differences

There are strong suggestions of inborn differences and wide variability in autonomic reactivity and temperament among individual infants. Chess and Thomas identified nine behavioral dimensions, in which reliable differences among infants can be observed (Table 31.1-6).

Table 31.1-6

Table 31.1-6

Temperament—Newborn to 6 Years

Most temperamental dimensions of individual children showed considerable stability over a 25-year follow-up period, but some temperamental traits did not persist. This finding was attributed to genetic and environmental effects on personality. A complex interplay exists among the initial characteristics of infants, the mode of parental interactions, and children’s subsequent behavior. Observations of the stability and plasticity of certain temperamental traits support the importance of interactions between genetic endowment (nature) and environmental experience (nurture) in behavior.

Attachment

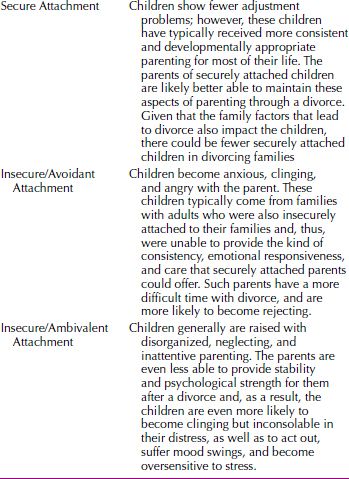

Bonding is the term used to describe the intense emotional and psychological relationship a mother develops for her baby. Attachment is the relationship the baby develops with its caregivers. Infants in the first months after birth become attuned to social and interpersonal interaction. They show a rapidly increasing responsivity to the external environment and an ability to form a special relationship with significant primary caregivers—that is, to form an attachment. Table 31.1-7 lists the commonly observed attachment styles.

Table 31.1-7

Table 31.1-7

Types of Attachment

Harry Harlow. Harry Harlow studied social learning and the effects of social isolation in monkeys. Harlow placed newborn rhesus monkeys with two types of surrogate mothers—one a wire-mesh surrogate with a feeding bottle and the other a wire-mesh surrogate covered with terry cloth. The monkeys preferred the terry-cloth surrogates, which provided contact and comfort, to the feeding surrogate. (When hungry, the infant monkeys would go to the feeding bottle but then would quickly return to the terry-cloth surrogate.) When frightened, monkeys raised with terry-cloth surrogates showed intense clinging behavior and appeared to be comforted, whereas those raised with wire-mesh surrogates gained no comfort and appeared to be disorganized. The results of Harlow’s experiments were widely interpreted as indicating that infant attachment is not simply the result of feeding.

Both types of surrogate-reared monkeys were subsequently unable to adjust to life in a monkey colony and had extraordinary difficulty learning to mate. When impregnated, the female monkeys failed to mother their young. These behavioral peculiarities were attributed to the isolates’ lack of mothering in infancy.

John Bowlby. John Bowlby studied the attachment of infants to mothers and concluded that early separation of infants from their mothers had severe negative effects on children’s emotional and intellectual development. He described attachment behavior, which develops during the first year of life, as the maintenance of physical contact between the mother and child when the child is hungry, frightened, or in distress.

Mary Ainsworth. Mary Ainsworth expanded on Bowlby’s observations and found that the interaction between mother and baby during the attachment period influences the baby’s current and future behavior significantly. Many observers believe that patterns of infant attachment affect future adult emotional relationships. Patterns of attachment vary among babies; for example, some babies signal or cry less than others. Sensitive responsiveness to infant signals, such as cuddling the baby when it cries, causes infants to cry less in later months. Close bodily contact with the mother when the baby signals for her is also associated with the growth of self-reliance, rather than clinging dependence, as the baby grows older. Unresponsive mothers produce anxious babies.

Ainsworth also confirmed that attachment serves to reduce anxiety. What she called the secured base effect enables a child to move away from the attachment figure and explore the environment. Inanimate objects, such as a teddy bear or a blanket (called the transitional object by Donald Winnicott), also serve as a secure base, one that often accompanies children as they investigate the world. A growing body of literature derived from direct observation of mother–infant interactions and longitudinal studies has expanded on, and refined, Ainsworth’s original descriptions. Maternal sensitivity and responsiveness are the main determinants of secure attachment. But when the attachment is insecure, the type of insecurity (avoidant, anxious, or ambivalent) is determined by infant temperament. Overall, male infants are less likely to have secure attachments and are more vulnerable to changes in maternal sensitivity than are female infants.

The attachment of the firstborn child is decreased by the birth of a second, but it is decreased much more when the firstborn is 2 to 5 years of age when the younger sibling is born than when the firstborn is younger than 24 months. Not surprisingly, the extent of the decrease also depends on the mother’s own sense of security, confidence, and mental health.

Social Deprivation Syndromes and Maternal Neglect. Investigators, especially René Spitz, have long documented the severe developmental retardation that accompanies maternal rejection and neglect. Infants in institutions characterized by low staff-to-infant ratios and frequent turnover of personnel tend to display marked developmental retardation, even with adequate physical care and freedom from infection. The same infants, placed in adequate foster or adoptive care, exhibit marked acceleration in development.

Fathers and Attachment. Babies become attached to fathers as well as to mothers, but the attachment is different. Generally, mothers hold babies for caregiving, and fathers hold babies for purposes of play. Given a choice of either parent after separation, infants usually go to the mother, but if the mother is unavailable they turn to the father for comfort. Babies raised in extended families or with multiple caregivers are able to establish many attachments.

Stranger Anxiety. A developmentally expected fear of strangers is first noted in infants at about 26 weeks of age, and more fully developed by 32 weeks (8 months). At the approach of a stranger, infants cry and cling to their mothers. Babies exposed to only one caregiver are more likely to have stranger anxiety than babies exposed to a variety of caregivers. Stranger anxiety is believed to result from a baby’s growing ability to distinguish caregivers from all other persons.

Separation anxiety, which occurs between 10 and 18 months of age, is related to stranger anxiety but is not identical to it. Separation from the person to whom the infant is attached precipitates separation anxiety. Stranger anxiety, however, occurs even when the infant is in the mother’s arms. The infant learns to separate as it starts to crawl and move away from the mother, but the infant constantly looks back and frequently returns to the mother for reassurance.

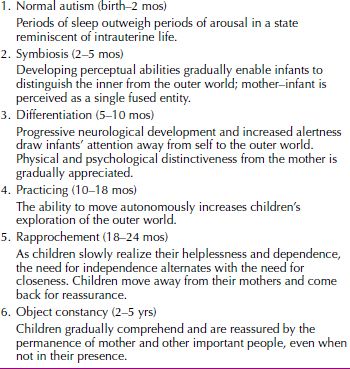

Margaret Mahler (1897–1985) proposed a theory to describe how young children acquire a sense of identity separate from that of their mothers’. Her theory of separation–individuation was based on observations of the interactions of children and their mothers. Mahler’s stages of separation–individuation are outlined in Table 31.1-8.

Table 31.1-8

Table 31.1-8

Stages of Separation-Individuation Proposed by Mahler

Infant Care

Clinicians are now beginning to view infants as important actors in the family drama, ones who partly determine its course. Infants’ behavior controls mothers’ behavior, just as mothers’ behavior modulates infants’ behavior. A calm, smiling, predictable infant is a powerful reward for tender maternal care. A jittery, irregular, irritable infant tries a mother’s patience. When a mother’s capacity for giving is marginal, such infant traits may cause her to turn away from her child and thus complicate the child’s already-troubled beginnings.

Parental Fit

Parental fit describes how well the mother or father relates to the newborn or developing infant; the idea takes into account temperamental characteristics of both parent and child. Each newborn has innate psychophysiological characteristics, which are known collectively as temperament. Chess and Thomas identified a range of normal temperamental patterns, from the difficult child at one end of the spectrum to the easy child at the other end.

Difficult children, who make up 10 percent of all children, have a hyperalert physiological makeup. They react intensely to stimuli (cry easily at loud noises), sleep poorly, eat at unpredictable times, and are difficult to comfort. Easy children, who make up 40 percent of all children, are regular in eating, eliminating, and sleeping; they are flexible, can adapt to change and new stimuli with a minimum of distress, and are easily comforted when they cry. The other 50 percent of children are mixtures of these two types. The difficult child is harder to raise and places greater demands on the parent than the easy child. Chess and Thomas used the term goodness of fit to characterize the harmonious and consonant interaction between a mother and a child in their motivations, capacities, and styles of behavior. Poor fit is likely to lead to distorted development and maladaptive functioning. A difficult child must be recognized, because parents of such infants often have feelings of inadequacy and believe that they are doing something wrong to account for the child’s difficulty in sleeping and eating and their problems comforting the child. In addition, most difficult children have emotional disturbances later in life.

Good-Enough Mothering. Winnicott believed that infants begin life in a state of nonintegration, with unconnected and diffuse experiences, and that mothers provide the relationship that enables infants’ incipient selves to emerge. Mothers supply a holding environment in which infants are contained and experienced. During the last trimester of pregnancy and for the first few months of a baby’s life, the mother is in a state of primary maternal preoccupation, absorbed in fantasies about, and experiences with, her baby. The mother need not be perfect, but she must provide good-enough mothering. She plays a vital role in bringing the world to the child and offering empathic anticipation of the infant’s needs. If the mother can resonate with the infant’s needs, the baby can become attuned to its own bodily functions and drives that are the basis for the gradually evolving sense of self.

TODDLER PERIOD

The second year of life is marked by accelerated motor and intellectual development. The ability to walk gives toddlers some control over their own actions; this mobility enables children to determine when to approach and when to withdraw. The acquisition of speech profoundly extends their horizons. Typically, children learn to say “no” before they learn to say “yes.” Toddlers’ negativism is vital to the development of independence, but if it persists, oppositional behavior connotes a problem.

Learning language is a crucial task in the toddler period. Vocalizations become distinct, and toddlers can name a few objects and make needs known in one or two words. Near the end of the second year and into the third year, toddlers sometimes use short sentences. The pace of language development varies considerably from child to child, and although a small number of children are truly late developers, most child experts recommend a hearing test if the child is not making two-word sentences by age 2.

Developmental Milestones in Toddlers

Language and Cognitive Development. Toddlers begin to listen to explanations that can help them tolerate delay. They create new behaviors from old ones (originality) and engage in symbolic activities, for instance, using words and playing with dolls when the dolls represent something, such as a feeding sequence. Toddlers have varied capacities for concentration and self-regulation.

Emotional and Social Development. In the second year, pleasure and displeasure become further differentiated. Social referencing is often apparent at this age; the child looks to parents and others for emotional cues about how to respond to novel events. Toddlers show exploratory excitement, assertive pleasure, and pleasure in discovery and in developing new behavior (e.g., new games), including teasing and surprising or fooling the parent (e.g., hiding). The toddler has capacities for an organized demonstration of love, as when the toddler runs up and hugs, smiles, and kisses the parent at the same time, and of protest when the toddler turns away, cries, bangs, bites, hits, yells, and kicks. Comfort with family and apprehension with strangers may increase. Anxiety appears to be related to disapproval and the loss of a loved caregiver and can be disorganizing.

Sexual Development. Sexual differentiation is evident from birth, when parents start dressing and treating infants differently because of the expectations evoked by sex typing. Through imitation, reward, and coercion, children assume the behaviors that their cultures define as appropriate for their sexual roles. Children exhibit curiosity about anatomical sex. When their curiosity is recognized as healthy and is met with honest, age-appropriate replies, children acquire a sense of the wonder of life and are comfortable with their own roles. If the subject of sex is taboo and children’s questions are rebuffed, shame and discomfort may result.

Gender identity, the conviction of being male or female, begins to manifest at 18 months of age and is often fixed by 24 to 30 months. It was once widely believed that gender identity was primarily a function of social learning. John Money reported on children with ambiguous or damaged external genitalia who were raised as the sex opposite to their chromosomal sex. Long-term follow-up of those individuals suggests that the major part of gender identity is innate and that rearing may not affect the genetic diathesis.

Gender role describes the behavior that society deems appropriate for one sex or another, and it is not surprising that significant cultural differences exist. There may be different expectations for boys and girls in what and with whom they play, their tone of voice, the expression of emotions, and how they dress. Nevertheless, some generalizations are possible. Boys are more likely than girls to engage in rough and tumble play. Mothers talk more to girls than to boys, and by the time the child is 2 years of age, fathers generally pay more attention to boys. Many educated, middle-class parents determined to raise nonsexist children are startled to see their children’s determined preference for sex-stereotyped toys: girls want to play with dolls, and boys with guns.

Toilet Training. The second year of life is a period of increasing social demands on children. Toilet training serves as a paradigm of the family’s general training practices; that is, the parent who is overly severe in the area of toilet training is likely to be punitive and restrictive in other areas also. Control of daytime urination is usually complete by the age of 2½, and control of nighttime urination is usually complete by the age of 4 years, when bowel control is usually accomplished. Since 1900, the pendulum has swung between extremes of permissiveness and control in toilet training. The trend in the United States has been toward delayed training, but in the last few years this trend appears to be shifting back to early training.

Toddlers may have sleep difficulties related to fear of the dark, which can often be managed by using a nightlight. Most toddlers generally sleep about 12 hours a day, including a 2-hour nap. Parents must be aware that children of this age may need reassurance before going to bed and that the average 2-year-old takes about 30 minutes to fall asleep.

Parenting Challenges. In infancy, the major responsibility for parents is to meet the infant’s needs in a sensitive and consistent fashion. The parental task in the toddler stage requires firmness about the boundaries of acceptable behavior and encouragement of the child’s progressive emancipation. Parents must be careful not to be too authoritarian at this stage; children must be allowed to operate for themselves and to learn from their mistakes and must be protected and assisted when challenges are beyond their abilities.

During the toddler period, children are likely to struggle for the exclusive affection and attention of their parents. This struggle includes rivalry, both with siblings and with one or another parent for the star role in the family. Although children are beginning to be able to share, they do so reluctantly. When the demands for exclusive possession are not resolved effectively, the result is likely to be jealous competitiveness in relationships with peers and lovers. The fantasies aroused by the struggle lead to fear of retaliation and to displacement of fear onto external objects. In an equitable, loving family a child elaborates a moral system of ethical rights. Parents need to balance between punishment and permissiveness and set realistic limits on a toddler’s behavior.

PRESCHOOL PERIOD

The preschool period is characterized by marked physical and emotional growth. Generally, between 2 and 3 years of age, children reach half their adult height. The 20 baby teeth are in place at the beginning of the stage, and by the end they begin to fall out. Children are ready to enter school by the time the stage ends at age 5 or 6. They have mastered the tasks of primary socialization—to control their bowels and urine, to dress and feed themselves, and to control their tears and temper outbursts, at least most of the time.

The term preschool for the age group of 2½ to 6 years may be a misnomer; many children are already in school-like settings, such as preschool nurseries and day care centers, where working mothers must often place their children. Preschool education can be valuable, but stressing academic advancement too far beyond a child’s capabilities can be counterproductive.

Developmental Milestones in Preschoolers

Language and Cognitive Development. In the preschool period, children’s use of language expands, and they use sentences. Individual words have regular and consistent meanings at the beginning of the period, and children begin to think symbolically. In general, however, their thinking is egocentric; they cannot place themselves in the position of another child and are incapable of empathy. Children think intuitively and prelogically and do not understand causal relations.

Emotional and Social Behavior. At the start of the preschool period, children can express such complex emotions as love, unhappiness, jealousy, and envy, both preverbally and verbally. Their emotions are still easily influenced by somatic events, such as tiredness and hunger. Although they still think mostly egocentrically, children’s capacity for cooperation and sharing is emerging. Anxiety is related to loss of a person who was loved and depended on and to loss of approval and acceptance. Although still potentially disorganizing, anxiety can be tolerated better than in the past. Four-year-olds are learning to share and to have concern for others. Feelings of tenderness are sometimes expressed. Anxiety over bodily injury and the loss of a loved person’s approval is sometimes disruptive.

By the end of the preschool period, children have many relatively stable emotions. Expansiveness, curiosity, pride, and gleeful excitement related to the self and the family are balanced with coyness, shyness, fearfulness, jealousy, and envy. Shame and humiliation are evident. Capacities for empathy and love are developed but are fragile and easily lost if competitive or jealous strivings intervene. Anxiety and fears are related to bodily injury and loss of respect, love, and emerging self-esteem. Guilt feelings are possible.

Children between the ages of 3 and 6 years are aware of their bodies, and of differences between the sexes. In their play, doctor–nurse games allow children to act out their sexual fantasies. Their awareness of their bodies extends beyond the genitalia; they show a preoccupation with illness or injury, so much so that the period has been called “the Band-Aid phase.” Every injury must be examined and taken care of by a parent.

Children develop a division between what they want and what they are told to do. The division increases until a gap grows between their set of expanded desires, their exuberance at unlimited growth, and their parents’ restrictions; they gradually turn parental values into self-obedience, self-guidance, and self-punishment.

At the end of the preschool stage, the child’s conscience is evolving. The development of a conscience sets the tone for the moral sense of “right and wrong.” Until about 7 years of age, children typically experience rules as “absolute” and as existing for their own sake. They do not understand that more than one point of view on a moral issue may exist; a violation of the rules calls for absolute retribution—that is, children have the notion of immanent justice.

SIBLING RIVALRY. In the preschool period, children relate to others in new ways. The birth of a sibling (a common occurrence during this time) tests a preschool child’s capacity for further cooperation and sharing but may also evoke sibling rivalry, which is most likely to occur at this time. Sibling rivalry depends on child-rearing practice. Favoritism for any reason commonly aggravates such rivalry. Children who get special treatment because they are gifted, are defective in some way, or have a preferred gender are likely to receive angry feelings from their siblings. Experiences with siblings can influence growing children’s relationships with peers and authority; for example, a problem may result if the needs of a new baby prevent the mother from attending to a firstborn child’s needs. If not handled properly, the displacement of the firstborn can be a traumatic event.

PLAY. In the preschool years, children begin to distinguish reality from fantasy, and play reflects this growing awareness. Pretend games are popular and help test real-life situations in a playful manner. Dramatic play in which children act out a role, such as a housewife or a truck driver, is common. One-to-one play relationships advance to complicated patterns with rivalries, secrets, and two-against-one intrigues. Children’s play behavior reflects their level of social development.

Between 2½ and 3 years, children commonly engage in parallel play, solitary play alongside another child with no interaction between them. By age 3, play is often associative, that is, playing with the same toys in pairs or in small groups, but still with no real interaction among them. By age 4, children are usually able to share and engage in cooperative play. Real interactions and taking turns become possible.

Between 3 and 6 years of age, growth can be traced through drawings. A child’s first drawing of a human being is a circular line with marks for the mouth, nose, and eyes; ears and hair are added later; arms and stick-like fingers appear next; and then legs appear. Last to appear is a torso in proportion to the rest of the body. Intelligent children can deal with details in their art. Drawings express creativity throughout a child’s development: They are representational and formal in early childhood, make use of perspective in middle childhood, and become abstract and affect-laden in adolescence. Drawings also reflect children’s body image concepts and sexual and aggressive impulses.

IMAGINARY COMPANIONS. Imaginary companions most often appear during preschool years, usually in children with above-average intelligence and usually in the form of persons. Imaginary companions may also be things, such as toys that are anthropomorphized. Some studies indicate that up to 50 percent of children between the ages of 3 and 10 years have imaginary companions at one time or another. Their significance is not clear, but these figures are usually friendly, relieve loneliness, and reduce anxiety. In most instances, imaginary companions disappear by age 12, but they can occasionally persist into adulthood.

MIDDLE YEARS

The period between age 6 and puberty is often called the middle years. During this time, children enter elementary school. The formal demands for academic learning and accomplishment become major determinants of further personality development.

Developmental Milestones in School-age Children

Language and Cognitive Development. In the middle years, language expresses complex ideas with relations among several elements. Logical exploration tends to dominate fantasy, and children show an increased interest in rules and orderliness and an increased capacity for self-regulation. During this period, children’s conceptual skills develop, and thinking becomes organized and logical. The ability to concentrate is well established by age 9 or 10, and by the end of the period, children begin to think in abstract terms. Improved gross motor coordination and muscle strength enable children to write fluently and draw artistically. They are also capable of complex motor tasks and activities, such as tennis, gymnastics, golf, baseball, and skateboarding.

Recent evidence has shown that changes in thinking and reasoning during the middle years result from maturational changes in the brain. Children are now capable of increased independence, learning, and socialization. Theorists consider moral development a gradual, stepwise process spanning childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

In the middle years, both girls and boys make new identifications with other adults, such as teachers and counselors. These identifications may so influence girls that their goals of wanting to marry and have babies, as their mothers did, may be combined with a desire for a career or may be postponed or abandoned entirely.

Girls who cannot identify with their mothers or whose fathers are overly attached may become fixated at about a 6-year-old level; as a result, they may fear men or women or both or become seductively close to them. In either case, such girls may not be seen as normal during the school-age years. A similar situation can occur in boys who have been unable to identify successfully with fathers who were aloof, brutal, or absent. Perhaps his mother prevented a boy from identifying with his father by being overprotective or by binding the son too closely to her. As a result, boys may enter this period with a variety of problems. They may be fearful of men, unsure of their sense of masculinity, or unwilling to leave their mothers (sometimes manifested by a school phobia); they may lack initiative and be unable to master school tasks, thus incurring academic problems.

The school-age period is a time when peer interaction assumes major importance. Interest in relationships outside the family takes precedence over those within the family. Nevertheless, a special relationship exists with the same-sex parent, with whom children identify and who is now an ideal and a role model.

Empathy and concern for others begin to emerge early in the middle years; by the time children are 9 or 10, they have well-developed capacities for love, compassion, and sharing. They have a capacity for long-term, stable relationships with family, peers, and friends, including best friends. Emotions about sexual differences begin to emerge as either excitement or shyness with the opposite sex. School-age children prefer to interact with children of the same sex. Although the middle years have sometimes been referred to as a latency period—a moratorium on psychosexual exploration and play until the eruption of sexual impulses with puberty—it is now recognized that a considerable amount of sexual interest continues through these years. Sex play and curiosity are common, especially among boys, but also among girls. Boys compare genitals and sometimes engage in group or mutual masturbation. An interest in anal humor and toilet jokes is often seen. Children this age often start using sexual and excretory words as expletives.

BEST FRIEND. Harry Stack Sullivan postulated that a buddy, or best friend, is an important phenomenon during the school years. By about 10 years of age, children develop a close same-sex relationship, which Sullivan believed is necessary for further healthy psychological growth. Moreover, Sullivan believed that the absence of a chum during the middle years of childhood is an early harbinger of schizophrenia.

SCHOOL REFUSAL. Some children refuse to go to school at this time, generally because of separation anxiety. A fearful mother may transmit her own fear of separation to a child, or a child who has not resolved dependence needs panics at the idea of separation. School refusal is usually not an isolated problem; children with the problem typically avoid many other social situations.

Sex Role Development

Persons’ sex roles are similar to their gender identity; persons see themselves as male or female. The sex role also involves identification with culturally acceptable masculine or feminine ways of behaving; but changing expectations in society (particularly in the United States) of what constitutes masculine and feminine behavior can create ambiguity.

Parents react differently to their male and female children. Independence, physical play, and aggressiveness are encouraged in boys; dependence, verbalization, and physical intimacy are encouraged in girls. Nowadays, however, boys are encouraged to verbalize their feelings and to pursue interests traditionally associated with girls, whereas girls are encouraged to pursue careers traditionally dominated by men and to participate in competitive sports. As society grows more tolerant in its expectations of the sexes, roles become less rigid, and opportunities for boys and girls enlarge and broaden.

Biologically, boys are more physically aggressive than girls; and parental expectations, particularly the expectations of fathers, reinforce this trait. Differences also exist between boys and girls in the influence of persons outside the family. Girls tend to respond to the expectations and opinions of girls and of teachers of either sex, but to ignore boys. Boys, on the other hand, tend to respond to other boys, but to ignore girls and teachers.

Dreams and Sleep

Children’s dreams can have a profound effect on behavior. During the first year of life, when reality and fantasy are not yet fully differentiated, dreams may be experienced as if they were, or could be, true. At age 3, many children believe dreams are shared directly by more than one person, but most 4-year-olds understand that dreams are unique to each person. Children view dreams either with pleasure or, as is most often reported, with fear. The dream content should be seen in connection with children’s life experience, developmental stage, mechanisms used during dreaming, and sex.

Disturbing dreams peak when children are 3, 6, and 10 years of age. Two-year-old children may dream about being bitten or chased; at the age of 4, they may have many animal dreams and also dream of persons who either protect or destroy. At age 5 or 6, dreams of being killed or injured, of flying and being in cars, and of ghosts become prominent; the role of conscience, moral values, and increasing conflicts are concerned with these themes. In early childhood, aggressive dreams rarely seem to occur; instead, dreamers are in danger, a state that perhaps reflects children’s dependent position. By about the age of 5, children realize that their dreams are not real; before then, they believed them to be real events. By age 7, children know that they create their dreams themselves.

Between the ages of 3 and 6 years, children normally want to keep their bedroom door open or to have a nightlight, so that they can either maintain contact with their parents or view the room in a realistic, nonfearful way. At times, children resist going to sleep to avoid dreaming. Disorders associated with falling asleep, therefore, are often connected with dreaming. Children often create rituals to protect themselves in the withdrawal from the world of reality into the world of sleep. Parasomnias, such as sleepwalking, sleep talking, enuresis (bed-wetting), and night terrors, are common at this age. They usually occur during stage 4 sleep when dreaming is minimal, and they do not indicate emotional trouble or underlying psychopathology. Most children grow out of parasomnias by adolescence.

Periods of REM occur about 60 percent of the time during the first few weeks of life, a period when infants sleep two thirds of the time. Premature babies sleep even longer than full-term babies, and a greater proportion of their sleep is REM sleep. The sleep–wake cycle of newborns is about 3 hours long. Among adults, the dream-to-sleep ratio is stable: 20 percent of sleeping time is spent dreaming. Even newborns have brain activity similar to that of the dreaming state.

Birth Spacing

For women in the United States, 10 percent of conceptions that lead to live births are considered unwanted, and 20 percent are wanted but considered ill timed.

Children born close together have higher rates of premature or underweight births, and malnutrition; they develop more slowly and are at increased risk of contracting and dying from childhood infectious diseases. Studies have shown when a child is born 3 to 5 years after a previous birth, health risks are reduced for both mother and child. Compared with 24- to 29-month intervals, children born in 36- to 41-month intervals are associated with a 28 percent reduction in stunting and a 29 percent reduction of low birth weight. Women who have children at 27- to 32-month intervals are 1.3 times more likely to avoid anemia, 1.7 times more likely to avoid third-trimester bleeding, and 2.5 times more likely to survive childbirth.

Birth Order

The effects of birth order vary. Firstborn children are often more highly valued and given more attention than subsequent children. Firstborn children appear to be more achievement oriented and motivated to please their parents than subsequent children born to the same parents. Some studies show that people in certain competitive occupational areas, such as architecture, accounting, and engineering, tend to be firstborn children.

Second and third children have the advantage of their parents’ previous experience. Younger children also learn from their older siblings. For example, they may show more sophisticated use of pronouns at an earlier age than firstborns did. When children are spaced too closely, however, there may not be enough time for each child. The arrival of new children in the family affects not only the parents but also the siblings. Firstborn children may resent the birth of a new sibling, who threatens their sole claim on parental attention. In some cases, regressive behavior, such as enuresis or thumb-sucking, occurs.

According to Frank Sulloway, firstborn children tend to be conservative and conformists; by contrast, youngest children tend to be independent and rebellious in regard to family and cultural norms. Sulloway found that a high proportion of prominent persons were lastborn children. He ascribes these differences to birth order and suggests that each child develops personality traits to fit an unfilled slot in the family. His findings need to be replicated.

Children and Divorce

Many children live in homes in which divorce has occurred. Approximately 30 to 50 percent of all children in the United States live in homes in which one parent (usually the mother) is the sole head of the household, and 61 percent of all children born in any given year can expect to live with only one parent before they reach the age of 18 years. A child’s age at the time of the parents’ divorce affects the child’s reaction to the divorce. Immediately after a divorce, an increase in behavioral and emotional disorders appears in all age groups. Infants do not understand anything about separation or divorce; however, they do notice changes in their parents’ responses to them and may experience changes in their eating or sleeping patterns; have bowel problems; and seem more fretful, fearful, or anxious. Children 3- to 6-years of age may not understand what is happening, and those who do understand often assume that they are somehow responsible for the divorce. Older children, especially adolescents, comprehend the situation and may believe that they could have prevented the divorce had they intervened in some way, but they are still hurt, angry, and critical of their parents’ behavior.

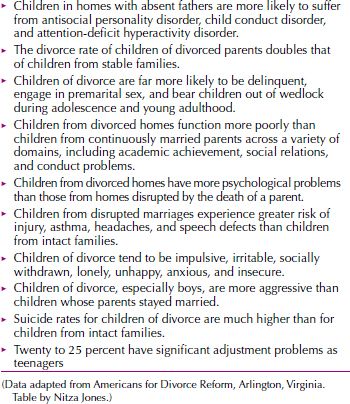

Some children harbor the fantasy that their parents will be reunited in the future. Such children may show animosity toward a parent’s real or potential new mate because they are faced with the reality that reconciliation between their parents is not taking place. Adaptation to the effects of divorce in children typically takes several years; however, up to about one third of children from divorced homes may have lasting psychological trauma. Among boys, physical aggression is a common sign of distress. Adolescents tend to spend more time away from the parental home after the divorce. Children who adapt best to divorce are typically in a situation in which both parents make genuine efforts to spend time and relate to the child despite the child’s potential anger about the divorce. To facilitate adaptation in children, a divorced couple who are amicable, and avoid arguing with one another is most likely to succeed. Table 31.1-9 lists potential psychological effects of divorce on children.

Table 31.1-9

Table 31.1-9

Effects of Divorce on Children

Stepparents. Although there are many different scenarios that may occur after a divorce and remarriage, several potential scenarios have been outlined in Table 31.1-10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree