Chapter 5 Childhood and child health

Childhood is a process of transition from vulnerability and high dependence towards autonomy. The risk of serious ill health interfering in this process has been significantly reduced in most affluent countries, but there is still a disproportionate excess of deaths and morbidity amongst the children of poorer families.

Children’s health

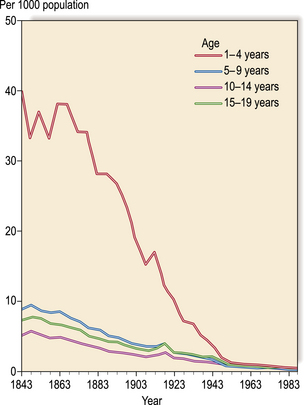

Relatively few children in affluent countries now die between the ages of 1 and 14 years. Improvements in children’s mortality occurred rapidly between 1870 and 1950 (Fig. 1), largely as a result of improvements in economic circumstances, living conditions, sanitation and nutrition leading to a decline in mortality from infectious and environmental disease. Since the 1950s, deaths in childhood have continued to decline steadily, though the UK still has an under-5-year-old mortality rate that is higher than most other European countries, possibly reflecting the greater levels of income inequality in the UK (Collison et al., 2007). Greater national wealth, immunization, fertility control, medical advances and greater access to health services have also contributed to improvements in children’s health. However, deaths and emergency admissions to hospital for unintentional injuries (accidents) remain a cause for concern, and the decline in serious infectious diseases in children in affluent countries (see pp. 158–159) has also meant that congenital disorders and cancers have become relatively more predominant, (see pp. 110–111).

Fig. 1 Trend in mortality under 20 years 1841–45 to 1986–90, England and Wales.

(adapted from Woodroffe et al., 1993)

Minor ill health is common in children and is mostly managed within the family, with the frequency of consultations with a doctor reducing as the child gets older (see pp. 88–89, 100–101).

Psychological health and behavioural problems

There is evidence that adverse family factors, such as a marriage with low mutual support, are related to behavioural problems in children aged 3 years, and to the onset of behavioural problems when older. However, patterns of problem behaviour, such as sleep disturbance, challenging behaviour and temper tantrums, do not always disappear if stress factors are reduced. Counselling and psychotherapy approaches to behaviour problems would suggest that learned patterns of behaviour are often deeply internalized in the subconscious and may be difficult to change (see pp. 22–23, 132–135). Furthermore, neglect and abuse of children are known predictors of depression and emotional/behavioural problems later in life for both men and women.