Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia

CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (referred to as myalgic encephalomyelitis in the United Kingdom and Canada) is characterized by 6 months or more of severe, debilitating fatigue, often accompanied by myalgia, headaches, pharyngitis, low-grade fever, cognitive complaints, gastrointestinal symptoms, and tender lymph nodes. The search continues for an infectious cause of chronic fatigue because of the high percentage of patients who report abrupt onset after severe flu-like illness.

The syndrome of chronic, debilitating fatigue has been an important clinical syndrome for psychiatry and neurology since the post–Civil War era in the 19th century. At the time the condition was known as neurasthenia or neurocirculatory asthenia. The disorder decreased in frequency during the mid-20th century but reappeared in the United States in the mid-1980s. In 1988, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defined specific diagnostic criteria for CFS. The disorder is classified in the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) as an ill-defined condition of unknown etiology under the heading “Malaise and Fatigue” and is subdivided into asthenia and unspecified disability.

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of CFS are unknown, but the incidence ranges from 0.007 percent to 2.8 percent in the general adult population. The illness is observed primarily in young adults (ages 20 to 40). CFS also occurs in children and adolescents but at a lower rate. Women are at least twice as likely as men to be affected.

In the United States, studies show that about 25 percent of the general adult population experience fatigue lasting 2 weeks or longer. When the fatigue persists beyond 6 months, it is defined as chronic fatigue. The symptoms of chronic fatigue often coexist with other illnesses, such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and temporomandibular joint disorder.

Etiology

The cause of the disorder is unknown. The diagnosis can be made only after all other medical and psychiatric causes of chronic fatiguing illness have been excluded. Scientific studies have validated no pathognomonic signs or diagnostic tests for this condition.

Investigators have tried to implicate the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) as the etiological agent in CFS. EBV infection, however, is associated with specific antibodies and atypical lymphocytosis, which are absent in CFS. Results of tests for other viral agents, such as enteroviruses, herpesvirus, and retroviruses, have been negative. Some investigators have found nonspecific markers of immune abnormalities in patients with CFS; for example, reduced proliferation responses of peripheral blood lymphocytes, but these responses are similar to those detected in some patients with major depression.

Several reports have shown a disruption in the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis (HPA) in patients with CFS, with mild hypocortisolism. Because of this, exogenous cortisol has been used to reduce fatigue but with equivocal results. Cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-alfa and interleukin (IL)-6 are under investigation as possible etiologic factors. Elevated levels have been found in the brains of some patients with CFS.

Some magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have found a decrease in volumetric regional gray and white matter in patients with CFS.

CFS may be familial. In one study, the correlation within twin pairs for monozygotic twins was more than 2.5 times greater than the correlation for dizygotic twins. Further studies are needed, however.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

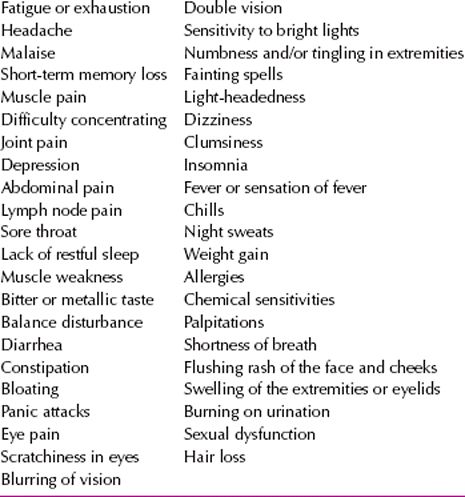

Because CFS has no pathognomonic features, diagnosis is difficult. Physicians should attempt to delineate as many signs and symptoms as possible to facilitate the process. Although chronic fatigue is the most common complaint, most patients have many other symptoms (Table 14-1). As a patient’s history unfolds, clinicians are likely to think of a variety of disease states that fall within the range of neurological, metabolic, or psychiatric disorders to account for the patient’s distress. In most cases, however, no picture of any disorder clearly emerges from history taking alone.

Table 14-1

Table 14-1

Signs and Symptoms Reported by Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

The physical examination is also an unreliable source of diagnostic certainty. In addition to chronic fatigue, for example, patients may complain of feeling warm or having chills with normal body temperature, and others may complain of lymph node tenderness in the absence of node enlargement. These and other equivocal findings neither confirm nor rule out the disorder.

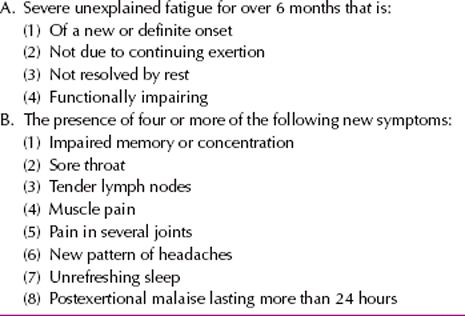

The CDC diagnostic criteria for CFS, which are listed in Table 14-2, include fatigue for at least 6 months, impaired memory or concentration, sore throat, tender or enlarged lymph nodes, muscle pain, arthralgias, headache, sleep disturbance, and postexertional malaise. Fatigue, the most obvious symptom, is characterized by severe mental and physical exhaustion, sufficient to cause a 50 percent reduction in patients’ activities. The onset is usually gradual, but some patients have an acute onset that resembles a flu-like illness.

Table 14-2

Table 14-2

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Criteria for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

In some cases, a noticeable correlation exists between CFS and neurally mediated hypotension, an autonomic nervous system dysfunction. It has been suggested that patients presenting with CFS symptoms undergo a tilt-table test to delineate symptoms attributable to hypotension so that they may be placed on appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree