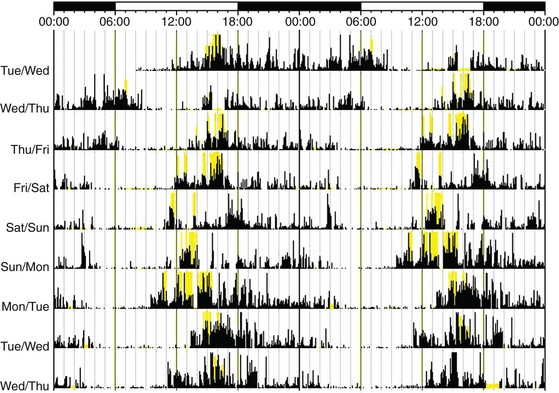

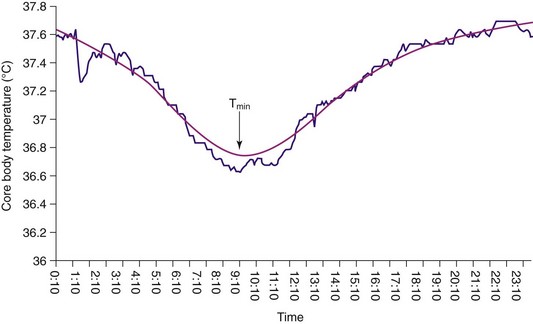

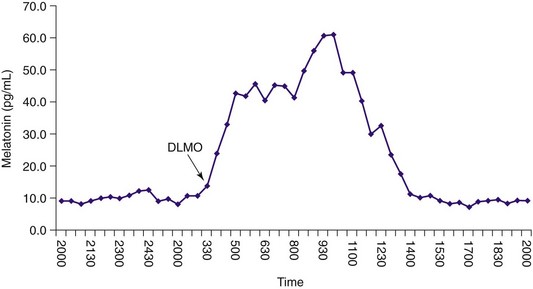

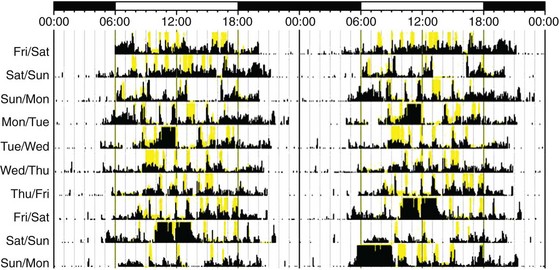

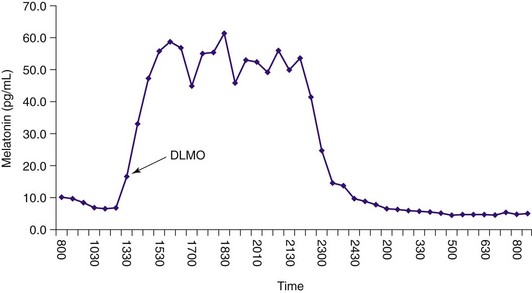

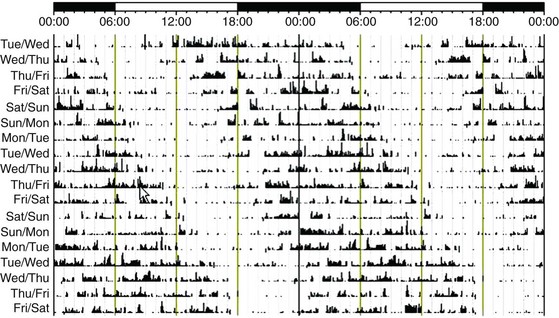

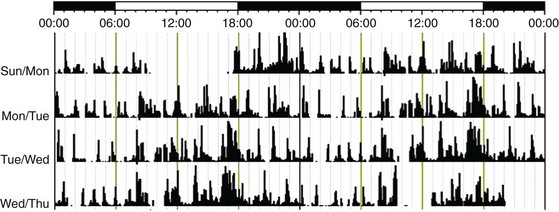

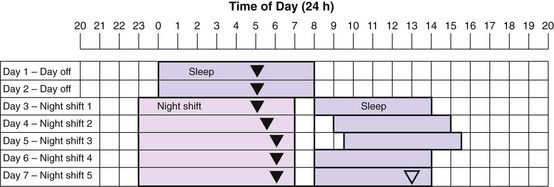

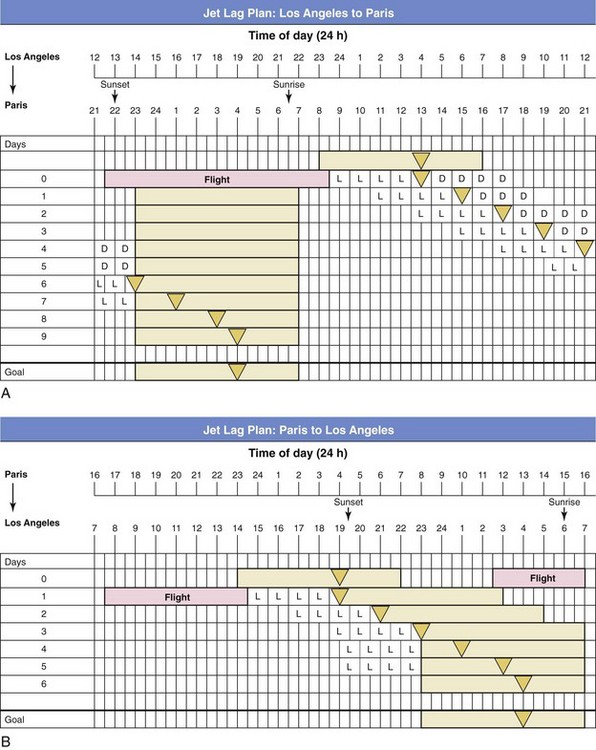

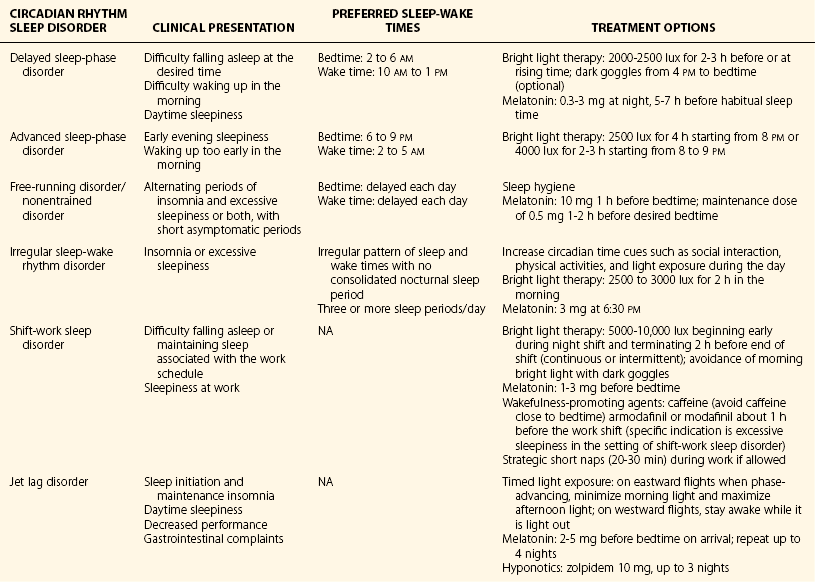

Chapter 9 9.1 Circadian Rhythm Disorders Delayed sleep-phase disorder (DSPD) is characterized by difficulty falling asleep and waking at the desired time and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS). This disorder is relatively common in adolescents, with a reported prevalence of approximately 7%, and in the general population, with a prevalence of roughly 0.17%. Individuals with DSPD typically have a delayed sleep-wake cycle, with sleep onset between 2 and 6 am and wake time between 10 am and 2 pm (Fig. 9.1-1). Figure 9.1-1 An example of the rest-activity cycle in a patient with delayed sleep-phase disorder recorded with wrist-activity monitoring. In addition to a delay in the sleep-wake cycle, a delay is seen in other circadian rhythm phase markers, such as core body temperature and the dim-light melatonin rhythm (Fig. 9.1-2). Determination of the endogenous melatonin rhythm can serve as a useful marker for the timing of circadian rhythms to aid in assessing the severity of the circadian delay and in optimally timing treatment interventions (Fig. 9.1-3). Figure 9.1-2 A 24-hour core body temperature (CBT) rhythm in an individual with delayed sleep-phase disorder. Figure 9.1-3 A 24-hour melatonin profile obtained under dim light conditions in a patient with delayed sleep-phase disorder. Advanced sleep-phase disorder (ASPD) is characterized by a difficulty staying awake in the evening and waking too early in the morning before the desired time (Fig. 9.1-4). In addition to an advance in the sleep-wake cycle, an advance is seen in other circadian rhythm phase markers, such as core body temperature and the dim-light melatonin rhythm (Fig. 9.1-5). The prevalence of ASPD in the general population is unknown and is believed to be rare, but it has been reported to be more common in older adults. ASPD has a genetic basis; in familial ASPD, the PER2 gene seems to be involved. Figure 9.1-4 An example of the rest-activity cycle in a patient with advanced sleep-phase disorder recorded with wrist-activity monitoring. Figure 9.1-5 This 24-hour profile of melatonin levels indicates a patient with a dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) at about 2 pm (arrow), which is much earlier than normal (8 to 10 pm). Non–24-hour sleep-wake disorder is characterized by a progressive delay in the circadian clock and in the sleep-wake cycle that results in insomnia and sleepiness, depending on when sleep is attempted, in relation to the phase of the circadian clock. This disorder is most commonly seen in blind individuals but has also been reported after brain injury and in normal-sighted individuals (Fig. 9.1-6). Figure 9.1-6 An example of the rest-activity cycle in a patient with a free-running disorder recorded with wrist-activity monitoring. Patients with irregular sleep-wake disorder have at least three sleep periods across the day and night and lack a single, consolidated sleep period. This disorder is most commonly seen in institutionalized older adults and in children with intellectual disabilities (Fig. 9.1-7). Irregular sleep-wake disorder is thought to be the result of either dysfunction in the internal circadian pacemaker or a reduction in activity, light, or other important social cues that influence timing and amplitude of circadian rhythms. Treatment for irregular sleep-wake disorder aims to consolidate the nocturnal sleep period. Several approaches have been used, including increasing the exposure to circadian synchronizing agents, such as light and activity levels. In children with intellectual disabilities, daily exogenous melatonin administration has been successful. Figure 9.1-7 An example of the rest-activity cycle in a 75-year-old woman with irregular sleep-wake disorder recorded with wrist-activity monitoring. Shift-work sleep disorder is characterized by insomnia and sleepiness associated with the work schedule. This sleep disturbance should not be better explained by another current sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, mental disorder, medication use, or substance use disorder. The prevalence of shift-work sleep disorder is estimated to be about 10% of the night and rotating shift-work population (Fig. 9.1-8). Figure 9.1-8 Changes in the timing of the circadian clock in a typical night worker. Jet lag disorder can be treated by speeding the adjustment of the circadian clock to the new time zone or by treating the symptoms of insomnia and sleepiness. An example of how to speed the phase adjustment to an eastward and westward return flight is described in Figure 9.1-9. It has even been recommended that, if possible, the adjustment to the new time zone start before departure. Once the circadian clock has realigned to the new time zone, the symptoms of jet lag disorder should dissipate. The duration of symptoms depends on the number of time zones crossed and the direction of travel, but symptoms typically resolve within 1 to 2 weeks. Figure 9.1-9 Circadian misalignment that will occur following an eastward flight from Los Angeles to Paris and following the westward return flight from Paris to Los Angeles. Table 9.1-1 provides a summary of the clinical presentation, preferred sleep-wake times, and treatment options for each of the CRSDs described above. Most of the recommended treatments for CRSDs are derived from small, single-center studies; however, more large-scale, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to assess the efficacy and effectiveness of the currently available treatments and to develop improved behavioral and pharmacologic strategies. Table 9.1-1 Summary of the Clinical Presentation, Preferred Sleep-Wake Times, and Treatment Options for Each of the Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Circadian System Disorders

Delayed Sleep-Phase Type/Delayed Sleep-Phase Disorder

The dark lines indicate activity; yellow bars indicate light level. Where the black lines are absent, it can be inferred that the patient is asleep. The data are plotted twice to make it easier to see the rest-activity cycle over several days. Time is plotted across the x-axis and is between midnight and midnight over 2 days. The y-axis indicates the day of the week. For this individual, the average sleep onset is at about 4 am, and the wake time is around 12 pm.

Time is indicated on the x-axis, and temperature in degrees Celsius is shown on the y-axis. The temperature minimum (Tmin) occurs at about 9 am. The declining portion of the CBT rhythm begins at about 3 am, and the rising portion begins at about 11 am. This rhythm would make it difficult for this person to fall asleep earlier than 3 am or to wake before 11 am, and if he did wake before 11 am to get to work or class, he would most likely feel extremely sleepy because his CBT would still be low.

The arrow indicates the time of dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) at about 3 am, which is much later than normal (in normal controls, DLMO is usually between 8 and 10 pm). Because sleep onset usually occurs about 2 hours after the DLMO, this person may not be sleepy until around 2 am, making it difficult to fall asleep earlier than 4 am.

Advanced Sleep-Phase Type/Advanced Sleep-Phase Disorder

This patient has a sleep-onset time that ranged between 8 and 9 pm and a wake time between 4 and 5 am on most days.

Because sleep onset usually occurs about 2 hours after the DLMO, this person will likely be very sleepy at around 4 pm.

Non–24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder, Free-Running Type, and Nonentrained Type

The rest-activity cycle in those with free-running disorder typically progressively delays each day, so that at certain times the rest period occurs during the daytime. If the individual with free-running disorder attempts to sleep at night, when the circadian propensity for sleep has shifted to the daytime, he or she may experience insomnia at night and excessive daytime sleepiness.

Irregular Sleep-Wake Type and Irregular Sleep-Wake Disorder

Unlike the other rest-activity cycles shown, there is no consolidated sleep period; instead, multiple short naps/sleeps are taken across the 24-hour period.

Shift-Work Type and Shift-Work Disorder

Sleep periods are represented by the light purple bars. Nighttime shift-work periods are represented by the light pink bars. The triangles represent the timing of the minimum temperature (Tmin). The solid triangles show where the Tmin is likely to be on each day. The open triangle shows where the Tmin needs to phase-delay for complete reentrainment to occur. The symptoms caused by the misalignment between the daytime sleep period and the circadian clock will diminish greatly if the Tmin falls within the daytime sleep period. Because the circadian clock does not shift quickly, the shift worker is sleeping during the day, when the core temperature rhythm is high. As a result, night workers do not typically sleep as long during the day, so that the daytime sleep periods are only about 6 hours long. (Modified from Reid KJ, Burgess HL: Circadian sleep disorders. Prim Care 2005;32[2]:449-473.)

Jet Lag Type and Jet Lag Disorder

The shaded bars represent sleep times. The home and transitional temperature minimums are shown as triangles. L represents when to seek light, and D shows when to seek dark. A, Los Angeles to Paris is an eastward flight across nine time zones. Such eastward flights are particularly difficult to adjust to, and phase delays often result. This traveler, who normally sleeps from 11 pm to 7 am in Los Angeles (temperature minimum at 4 am) arrives in Paris in the early morning. Phase-advancing in these circumstances will be extremely difficult, and managing light exposure can be used to help phase delay. Even if travelers seek and avoid light at the correct times, they are still likely to experience jet lag for 6 to 7 days, until the temperature minimum falls into the desired sleep times. B, Jet lag plan for someone who travels nonstop from Paris to Los Angeles. Light exposure on arrival in Los Angeles is beneficial; if travelers have a flexible schedule, such that they go to sleep in a dark bedroom at 7 pm to ensure they avoid light after the temperature minimum, they will likely experience jet lag for only 3 to 4 days. (Modified from Burgess HJ: Using bright light and melatonin to reduce jet lag. In Perlis M, Aloia M, Kuhn B [eds]: Behavioral treatments for sleep disorders. Philadelphia, 2011, Elsevier.)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Circadian System Disorders

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue