Circular Feedback Model of Depression

After reviewing the relative strengths and limitations of CBT and hypnotherapy, it would appear clinically intuitive to combine the strengths of the two treatments. Such integration not only compensates for the shortcomings of each treatment, but also shapes clinical practice guidelines. This chapter describes a working model of depression referred as the circular feedback model of depression (CFMD) that provides the theoretical and empirical rationale for integrating CBT with hypnotherapy in the management of depression. This is a biopsychosocial model of depression, emphasizing the circular nature of the disorder. An important element of circularity is that it encourages intervention simultaneously at multiple levels. The major contribution of the model–beyond its value as an organizational tool–is its emphasis on functional autonomy and circular causality, so that factors such as cognitive distortions, negative ruminations, distressed relationships, adverse life events, and neurochemical changes are seen as both symptoms and causes at the same time. Before describing CFMD, the literature pertaining to hypnotherapy for depression is first reviewed.

Hypnotherapy for Depression

Despite the fact that depression is an urgent and widespread problem, hypnotherapy has not been widely used in the management of clinical depression. I (2006) believe this may be due to the erroneous belief among some writers and clinicians that hypnotherapy can exacerbate suicidal behaviors in depressed patients. For example, Hartland (1971) warned that “hypnosis should never be used in depressional states in which suicidal impulses are present unless the patient is an in-patient under hospital supervision” (p. 335; emphasis in original text). More recently, however, clinicians have proposed that hypnotherapy, when it forms part of a multimodal treatment approach, is not contraindicated in either inpatient or outpatient depressed patients (e.g., Alladin, 2006; Alladin & Heap, 1991; Yapko, 1992, 2001). For example, Yapko (1992) utilizes hypnotherapy to reduce symptoms of hopelessness, which is a predictor of suicidal behavior, in the early stages of his comprehensive approach to psychotherapy for depression. The bulk of the published literature on the application of hypnosis in the management of depression has consisted of case reports (Burrows & Boughton, 2001). Because of the great deal of variation in the techniques reported in these cases, it is difficult to compare directly the various

methods employed by individual therapists in the management of depression.

methods employed by individual therapists in the management of depression.

Nevertheless, a growing body of research evaluates the use of hypnotherapy with CBT in the treatment of various psychological disorders, although not specifically with depression. Schoenberger (2000), from her review of the empirical status of the use of hypnotherapy in conjunction with CBT, concluded that the existing studies demonstrate substantial benefits from the addition of hypnotherapy to cognitive-behavioral techniques. Similarly, Kirsch, Montgomery, and Sapirstein (1995), from their meta-analysis of 18 studies comparing CBT with the same treatment supplemented by hypnotherapy, found the mean effect size to be larger than the nonhypnotic treatment. The authors concluded that hypnotherapy was significantly superior to nonhypnotic treatment. Encouraged by these findings, several writers (e.g., Golden, Dowd, & Friedberg, 1987; Tosi & Baisden, 1984; Yapko, 2001) have described the integration of CBT and hypnotherapy with depression. Research undertaken by my associates and I (Alladin, 1989, 1992, 1994, 2006; Alladin & Heap, 1991) has provided a theoretical rationale and solid empirical foundation for combining these two treatment approaches. This is in marked contrast to the work of other researchers: Yapko (2001) remarks, “Therapeutic efficacy research involving hypnosis specifically for depression has, to this point, been essentially nonexistent” (p. 7).

My working model of nonendogenous depression, CDMD, provides a theoretical framework for integrating cognitive and hypnotic techniques with depression. Research data (Alladin, 2005, 2006; Alladin & Alibhai, 2007) have demonstrated an increase in effect size when hypnotherapy is combined with CBT in the management of chronic depression. We (Alladin, 2005; Alladin & Alibhai, 2007) compared the effects of CBT with cognitive hypnotherapy in 98 chronically depressed patients. The results showed an additive effect for combining hypnotherapy with CBT. The study also met criteria for probably efficacious treatment for depression as outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force (Chambless & Hollon, 1998), and it provides empirical validation for integrating hypnosis with CBT in the management of depression. The results of the study are discussed in greater detail under Effectiveness of Cognitive Hypnotherapy in 5. In this book, CDMD has been revised, refined, and renamed the circular feedback model of depression (CFMD).

Circular Feedback Model of Depression

CFMD is conceptualized to emphasize the circular and biopsychosocial nature of depression and to elucidate the role of multiple factors that can trigger, exacerbate, or maintain the depressive affect. The model is not a new theory of depression or an attempt to explain the causes of depression. It is an extension of Beck’s (1967) circular feedback model of depression, which was later elaborated on by Schultz (1978, 1984, 2003). This extended model combines cognitive and hypnotic paradigms, and it incorporates ideas and concepts from information processing, selective attention (cognitive distortion, rumination), brain functioning, adverse life experiences, and the neodissociation theory of

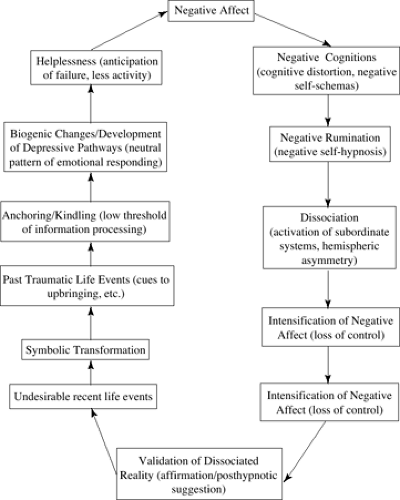

hypnosis. It is referred as the circular feedback model because it consists of 12 interrelated components that form a circular feedback loop (Fig. 4.1). From the review of the theories of depression in 1 and 2, it is apparent that depression is related to a host of interacting processes in the domains of physiological processes (genes and hormones), psychological factors (negative beliefs, rumination, and social withdrawal), and social factors (life events and social support) that interact over time (Akiskal & McKinney, 1975; Gilbert, 2004). The number of components forming the loop and the position of each component in the loop is arbitrary. The 12 components forming the circular loop represent some of the major sets of factors identified from the literature that may influence the onset, course, and outcome of depression. Any one of these 12 components, singly or in concert with other components, can synergistically trigger, exacerbate, or maintain the depressive affect. Moreover, the interaction among these components is dynamic, ongoing, and reciprocal in nature.

This chapter describes the model, then presents an integrated approach to treatment based on the model. This treatment approach is called cognitive hypnotherapy (CH). CH is a structured program of therapy, described in Part III of the book, that utilizes hypnotherapeutic methods along with orthodox cognitive and behavioral procedures (Alladin & Heap, 1991) in the treatment of depression. The 12 components are described in detail below, and the relationships among these components that form the depressive loop is highlighted.

hypnosis. It is referred as the circular feedback model because it consists of 12 interrelated components that form a circular feedback loop (Fig. 4.1). From the review of the theories of depression in 1 and 2, it is apparent that depression is related to a host of interacting processes in the domains of physiological processes (genes and hormones), psychological factors (negative beliefs, rumination, and social withdrawal), and social factors (life events and social support) that interact over time (Akiskal & McKinney, 1975; Gilbert, 2004). The number of components forming the loop and the position of each component in the loop is arbitrary. The 12 components forming the circular loop represent some of the major sets of factors identified from the literature that may influence the onset, course, and outcome of depression. Any one of these 12 components, singly or in concert with other components, can synergistically trigger, exacerbate, or maintain the depressive affect. Moreover, the interaction among these components is dynamic, ongoing, and reciprocal in nature.

This chapter describes the model, then presents an integrated approach to treatment based on the model. This treatment approach is called cognitive hypnotherapy (CH). CH is a structured program of therapy, described in Part III of the book, that utilizes hypnotherapeutic methods along with orthodox cognitive and behavioral procedures (Alladin & Heap, 1991) in the treatment of depression. The 12 components are described in detail below, and the relationships among these components that form the depressive loop is highlighted.

Fig 4.1. Circular feedback model of depression (CEMD) showing the constellation of 12 factors forming the depressive loop. |

Negative Affect and Negative Cognitions

Because the model attaches significant importance to the interaction between affect and cognition, the logical starting point for describing the depressive loop is to start with affect, which appears at the top of the loop (Fig. 4.1). The CFMD proposed by Beck (1967) maintains the existence of a mutually reinforcing interaction between cognition and affect so that thought not only influences feelings, but feelings too can influence thought content (hence the bidirectional arrows between Negative Affect and Negative Cognition in Fig. 4.1). Also, congruent with the concepts of the “bicameral brain” (Jaynes, 1976) and unconscious information processing (e.g., LeDoux, 2000), it is maintained that either affect or cognition can independently starts the chain process of the feedback loop (Fig. 4.1). The intimate association between dysfunctional cognition and depressive affect is well documented in the literature (e.g., Haas & Fitzgibbon, 1989; Haaga, Dyck, & Ernst, 1991). An event (internal or external) can trigger a negative schema that, through cognitive rehearsal, can lead to dissociation.

Negative Self-Hypnosis

Individuals predisposed to depression not only focus on negative thoughts but also on negative imagery. Schultz (1978), Starker and Singer (1975), and Traynor (1974) have provided evidence that with increasing levels of depression, depressed patients tend to change the content of their fantasies and focus more on negative topics. Such focusing generates negative imagery and leads to the maintenance and exacerbation of the depressed mood that initially produced the negative thinking. Consequently, depressed patients are unable to change the negative content of their imagination. Moreover, Schultz (1978) found that depressed patients are unable to redirect their thinking and imagery away from their current problems; hence, the depressive mood is continually reinforced. In other words, the circular feedback cycle between cognition and affect repeats itself almost like a computer reverberating through an infinite loop (Schultz, 1978). This process is very similar to the concept of negative self-hypnosis (NSH) proposed by Araoz (1981, 1985) to explain the maintenance of emotional disorders.

The concept of NSH can be easily extended to explain the persistence of the depressive process. Because depressed patients (when depressed) tend to be actively involved in NSH, it is not surprising that they have little success in breaking the affective circular feedback loop. This explains Schultz’s (1978) findings that depressed patients are unable to relieve depression through

nondirected or passive imagery. In fact, such nondirected imagery led to a worsening of the depression. On the other hand, active or directed imagery (since this did not allow indulgence in active NSH) led to a reduction in depression. NSH, in the context of depression, can be conceptualized as a form of depressive rumination.

nondirected or passive imagery. In fact, such nondirected imagery led to a worsening of the depression. On the other hand, active or directed imagery (since this did not allow indulgence in active NSH) led to a reduction in depression. NSH, in the context of depression, can be conceptualized as a form of depressive rumination.

Depressive Rumination

Depressive rumination is a common response to negative moods (Rippere, 1977). It can be crudely defined as persistent and recyclic depressive thinking (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2004). Rumination is not always negative. Research suggests rumination is a natural, normal phenomenon, providing us with a way of getting back on track with our goals (Papageorgiou & Wells, 1999). At times, however, rumination can be undesirable and counterproductive, thwarting individuals from goal attainment. In these instances, the ruminative state tends to persist. This is particularly noticeable among depressed patients. Nolen-Hoeksema and her colleagues have been instrumental in advancing our knowledge of ruminative thinking in depression. Nolen-Hoeksema (1991, 2004) proposed the response styles theory of depression, which conceptualizes rumination as repetitive and passive thinking about symptoms of depression and the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms. Several studies (see Papageorgiou & Wells, 2004) have provided evidence that depressed patients tend to ruminate for longer duration, exert little effort to problem-solve, express lower confidence in problem-solving, and have a greater orientation to the past. According to the response styles theory, depressive rumination exacerbates and prolongs symptoms of depression, and aggravates moderate symptoms of depression into major depressive episodes. Within the CFMD model, depressive rumination is conceptualized as a form cognitive distortion or NSH.

Nolen-Hoeksema (2004) has posited four mechanisms by which depressive rumination prolongs depression. First, rumination enhances the effects of depressed mood on cognitive distortions, thus potentiating negative appraisal of the current circumstances (based on memories activated by depressed mood). Second, rumination interferes with effective problem-solving by promoting pessimistic and fatalistic thinking. Third, rumination interferes with instrumental behavior. Finally, people who chronically ruminate lose social support, which in turn feeds on their depression. From their review of the large number of studies on ruminative responses to depressed mood, Lyubomirsky and Tkach (2004) demonstrated rumination to have negative consequences on thinking, motivation, concentration, problem-solving, instrumental behavior, and social support. Moreover, Nolen-Hoeksema (2000), using a community sample of 1,300 depressed adults, found rumination to be strongly related to the development of a mixed anxiety-depression syndrome. Content analyses of the ruminators’ ruminations revealed that anxiety was related to uncertainty over whether one will be able to control one’s environment, whereas depression was related to hopelessness about the future and negative evaluation of the self. In other words, ruminators may vacillate between anxiety and depression as

their cognition vacillates between uncertainty and hopelessness. This process partially explains the comorbid relationship between anxiety and depression.

their cognition vacillates between uncertainty and hopelessness. This process partially explains the comorbid relationship between anxiety and depression.

From this discussion it is evident that negative rumination is a potential risk factor for depression, and it plays an important part in the exacerbation and maintenance of the depressive affect. In this context, it is also not unreasonable to consider NSH as a form of negative rumination. Since the concept of rumination has been studied extensively, it is tempting to replace NSH with rumination. However, the concept of NSH is preserved in the model to encourage research on NSH and to emphasize the dissociative aspect of rumination. Studies of NSH in the context of depression are likely to provide further understanding on how attention is automatically directed toward negative self-relevant material to create a mental environment that is conducive to the intensification of negative affect and negative self-affirmations (negative posthypnotic suggestions). Studies of the relationship between NSH and depression are likely to provide insight into the phenomenological nature of the depressive state.

Conceptualization of Depression as Dissociation

NSH can be regarded as a form of dissociation. According to Araoz (1981, 1985), NSH consists of nonconscious (automatic) rumination with negative statements and defeatist mental images that the person indulges in, encourages, and often works hard at fostering–while at the same time consciously wanting to get better. Araoz calls this NSH because it is composed of three hypnotic components: (i) noncritical thinking that becomes a negative activation of subconscious processes, (ii) active negative imagery, and (iii) powerful posthypnotic suggestions in the form of negative affirmations. I (1992) contend that, like hypnosis, unipolar nonendogenous depression also involves all three components. Such a process can be readily observed in depressed patients, who are constantly ruminating on their alleged negative personal attributes, which can be regarded as a form of self-hypnotic induction. Although not making reference to hypnosis or dissociation, Beck, Rush, Shaw, and Emery (1979, p. 13) state:

In milder depressions the patient is generally able to view his negative thoughts with some objectivity. As the depression worsens, his thinking becomes increasingly dominated by negative ideas, although there may be no logical connection between actual situations and his negative interpretations.… In the more severe states of depression, the patient’s thinking may become completely dominated by the idiosyncratic schema: he is completely preoccupied with perseverative, repetitive negative thoughts and may find it enormously difficult to concentrate on external stimuli … or engage in voluntary mental activities.…

In such instances we infer that the idiosyncratic cognitive organization has become autonomous. The depressive cognitive organization may become so independent of external stimulation that the individual is unresponsive to changes in his immediate environment.

Because strong emotions narrow the focus of attention to affectively relevant events and exclude incidental stimuli

(Easterbrook, 1959), emotionally upset people, such as depressed patients, become poor learners (e.g., Beck, 1967); they are distracted away from alternative channels of information. During normal waking state, single-channel cognitive processing is normally involved (Shevrin & Dickman, 1980), but in such states as dream, intoxication, psychosis, multiple personality, and the like, the single-channel characteristic is not shared. Hilgard (1977) believes that multiple-channels (divided consciousness) may be involved in these states. Moreover, Hilgard (1977) takes the concept of “self” and “will” into consideration, and maintains that hypnosis and other dissociative experiences all involve some degree of loss of voluntary control, or a division of control. This is very noticeable in depressed patients, who report having very little self-esteem and have lost the will to do anything. Hilgard also talks about the central structure or the executive ego, which is normally in control, but that can be taken over by other subordinate structures as a result of hypnotic-type suggestions or other similar procedures or situations. In depression, the patient’s constant negative rumination can easily induce negative self-hypnosis (dissociation), which in turn can strengthen subordinate cognitive structures or schemas. Once these subordinate systems have been established, they can develop a certain degree of autonomy via rumination or self-hypnosis. Hence, activities that are normally under control may go out of voluntary control (partly or completely); consequently, the associated experiences may go out of normal awareness. Such focusing also leads to an impoverished construction of reality (i.e., based on selective information processing), permitting continual reinforcement of the depressive feedback loop. Neisser (1967) regards such narrowing down and distortion of the environment by a few repetitive behaviors and self-attributions as characteristic of psychopathology. In other words, once depressed individuals are involved in the depressive loop, their cognitive distortions become automatic (dissociative), and hence they are unable to focus on alternative thinking and images not related to their current problems and negative life concerns. I (1992) propose that negative rumination in some depressed patients may lead to a state of partial or profound dissociation.

(Easterbrook, 1959), emotionally upset people, such as depressed patients, become poor learners (e.g., Beck, 1967); they are distracted away from alternative channels of information. During normal waking state, single-channel cognitive processing is normally involved (Shevrin & Dickman, 1980), but in such states as dream, intoxication, psychosis, multiple personality, and the like, the single-channel characteristic is not shared. Hilgard (1977) believes that multiple-channels (divided consciousness) may be involved in these states. Moreover, Hilgard (1977) takes the concept of “self” and “will” into consideration, and maintains that hypnosis and other dissociative experiences all involve some degree of loss of voluntary control, or a division of control. This is very noticeable in depressed patients, who report having very little self-esteem and have lost the will to do anything. Hilgard also talks about the central structure or the executive ego, which is normally in control, but that can be taken over by other subordinate structures as a result of hypnotic-type suggestions or other similar procedures or situations. In depression, the patient’s constant negative rumination can easily induce negative self-hypnosis (dissociation), which in turn can strengthen subordinate cognitive structures or schemas. Once these subordinate systems have been established, they can develop a certain degree of autonomy via rumination or self-hypnosis. Hence, activities that are normally under control may go out of voluntary control (partly or completely); consequently, the associated experiences may go out of normal awareness. Such focusing also leads to an impoverished construction of reality (i.e., based on selective information processing), permitting continual reinforcement of the depressive feedback loop. Neisser (1967) regards such narrowing down and distortion of the environment by a few repetitive behaviors and self-attributions as characteristic of psychopathology. In other words, once depressed individuals are involved in the depressive loop, their cognitive distortions become automatic (dissociative), and hence they are unable to focus on alternative thinking and images not related to their current problems and negative life concerns. I (1992) propose that negative rumination in some depressed patients may lead to a state of partial or profound dissociation.

The circular feedback model, however, does not regard hypnosis or dissociation to be analogous to depression. Rather, it proposes that there are some commonalities in the style of cognitive processing and organization (depressive rumination) involved in the generation of the “state of hypnosis” and the “state of depression.” Since it is possible to hypnotically induce transient and long-lasting negative or positive psychological and physiological changes, hypnosis provides a paradigm for studying and understanding how negative ruminations produce and intensify depressive affect. My research (1992) has highlighted the similarities and differences between hypnosis and depression, and makes note of the fundamental difference between the two states in terms of cognitive contents and control. The cognitive contents of hypnosis can be either negative or positive, and they can be easily altered (easily controlled), whereas the cognitive contents of depression are invariably negative and not easily changed (not easily controlled). A variety of evidence (for a review see Tomarken & Keener, 1998)

indicates that depressed individuals, because of the relative hypoactivity of their left frontal brain, demonstrate enhanced negative affective responses to emotion elicitors (e.g., depressive rumination, negative affect) that are more likely to be sustained over time. This is caused by a heightened access to cognitive or other processes that serve to sustain negative affective reactions and decreased access to processes that inhibit negative affect to promote the positive-affect-induced counter-regulation of negative affect. Although indirectly describing how NHS produces the phenomenological experience of the depressive affect, this divided consciousness may also be involved in unipolar depression.

indicates that depressed individuals, because of the relative hypoactivity of their left frontal brain, demonstrate enhanced negative affective responses to emotion elicitors (e.g., depressive rumination, negative affect) that are more likely to be sustained over time. This is caused by a heightened access to cognitive or other processes that serve to sustain negative affective reactions and decreased access to processes that inhibit negative affect to promote the positive-affect-induced counter-regulation of negative affect. Although indirectly describing how NHS produces the phenomenological experience of the depressive affect, this divided consciousness may also be involved in unipolar depression.

Cerebral Lateralization in Depression and Hypnosis

In this section, neuropsychophysiological correlates of emotion, depression, imagery, rumination, and hypnosis are briefly reviewed to identify the similarities and differences in the brain correlates among these states and to integrate this information in the development of treatment strategies.

A variety of evidence indicates a linkage between depression and specific patterns of frontal brain asymmetry. Unilateral brain lesions, unilateral hemispheric sedation, electroencephalographic (EEG) studies, positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission tomography (SPECT), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and biochemical studies indicate that unipolar depression is associated with decreased activation of left-hemisphere frontal brain regions relative to right-hemisphere frontal regions (for a review, see Tomarken & Keener, 1998; Davidson, Pizzagalli, & Nitschke, 2002; Mayberg, 2006). Of prime importance from these findings is that (a) the resting frontal brain asymmetry may be a trait marker for vulnerability to depression, and (b) relative left-frontal hyper-activation may be linked to decreased vulnerability to depression and to a self-enhancing cognitive style that may promote such decreased vulnerability. However, at this point it is not known why brain asymmetry is linked to depression. Davidson (see Davidson, Pizzagalli, & Mitschke, 2002) has invoked the approach-withdrawal hypothesis to account for the linkage between frontal brain asymmetry and depression.

According to the approach-withdrawal hypothesis, relative left-frontal activation is associated with heightened appetitive or incentive motivation, heightened responsivity to rewards or other positive stimuli, and greater contact with those features of the external environment that are rewarding or engaging. Relative right-frontal activation is associated with a protective-defensive tendency to withdraw from potentially threatening stimuli (e.g., novel ones) or to avoid such stimuli. Several empirical findings support the approach-withdrawal hypothesis. For example, Calkins, Fox, and Marshall (1996) showed that children who display behavioral inhibition or social reticence are more likely to demonstrate relative right-frontal activation. Such children tend to withdraw from novel stimuli, whereas uninhibited children tend to approach such stimuli. The approach-withdrawal hypothesis is also consistent with the evidence that frontal brain

asymmetry is linked to depression or risk of depression (Henriques & Davidson, 1990). Henriques and Davidson (1990) purport that anhedonia and decreased reactivity to pleasurable stimuli linked with depression may reflect a deficit in a reward-oriented approach system. Studies also suggest the link between left-frontal hypoactivation in depression and a deficit in dopaminergic function (Ebert, Feistel, Kaschka, Barocka, & Pirner, 1994)

asymmetry is linked to depression or risk of depression (Henriques & Davidson, 1990). Henriques and Davidson (1990) purport that anhedonia and decreased reactivity to pleasurable stimuli linked with depression may reflect a deficit in a reward-oriented approach system. Studies also suggest the link between left-frontal hypoactivation in depression and a deficit in dopaminergic function (Ebert, Feistel, Kaschka, Barocka, & Pirner, 1994)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree