(1)

Princeton Spine & Joint Center, Princeton, NJ, USA

Keywords

AnatomySpineFacet jointsIntervertebral discsMusclesTendonsLigamentsNervesA chapter on clinical anatomy of the lumbosacral spine in a book like this can be challenging. On the one hand, if you don’t already know that there are five lumbar vertebrae in the lumbar spine, then you are reading the wrong book. On the other hand, if you do know that the L5 dorsal ramus is much longer than the other dorsal rami in the lumbar spine and that it runs along the groove between the sacral ala and the root of the S1 superior articular process [1], then this information will help you with a radiofrequency rhizotomy procedure (which is important if this is a procedure you perform) but not much else. In this chapter, we will attempt to thread that needle, to provide pertinent, high-yield clinical anatomy needed to diagnose and treat pathologies of the lumbar spine without delving into the surgical anatomy needed to perform complex procedures.

The Spine

Whether you are a physician thinking of the spine or a physician explaining the spine to your patient, it is helpful to think of the spine as similar to a mast on a sailboat. The bones, of course, are the mast. The muscles, tendons, and ligaments attaching to the spine are the riggings that attach to the mast. If a mast on a sailboat is not supported by the riggings, then the mast will fall over. The mast, in the end, cannot support its own weight and so it relies on all of the ropes that attach to it to unload it. Similarly, the human spine cannot support its own weight. Therefore, the spine relies on all of the muscles, tendons, and ligaments that attach to it in order to unload the spine so that it can function optimally and stay upright [2]. This is the reason that stretching and strengthening the lumbar stabilizing muscles are so important in treating the back and preventing subsequent injury. The lumbar stabilizing muscles support the spine, and if they are weak, imbalanced, or not integrated maximally, then the spine will experience unnecessary stress and premature degeneration.

Bones

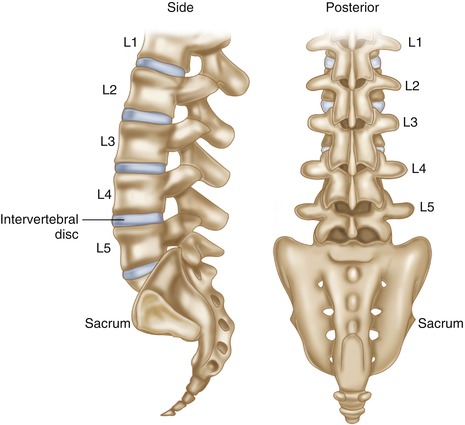

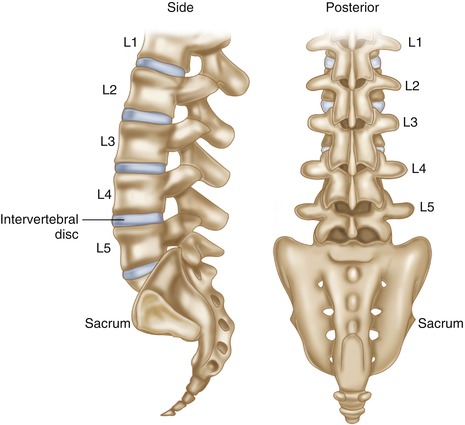

The bones of the lumbar spine serve three basic functions. They bear the weight of the spine, protect the neural elements traversing the spinal canal, and they articulate to provide for a great range of movements (flexion, extension, rotation). There are five lumbar vertebrae and the fifth lumbar veretbra articulates with the sacrum (Fig. 1.1). The lowest two lumbar segments, the L4–L5 and the L5–S1, in part because of the biomechanics of the natural lumbar lordosis, support the most weight of the spine and therefore are the most prone to suffering injuries and general degenerative changes [3, 4]. On the sides of the vertebral bodies are the facet joints (technically and more precisely termed zygapophyseal joints). The facet joints are synovial joints. These synovial joints are hinge joints that allow for flexion and resist extension and rotation (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.1

Schematic depiction of the lumbosacral spine with lumbar vertebrae numbering nomenclature

Fig. 1.2

Schematic depiction of the lumbosacral spine with facet joints identified

The sacrum is a large triangular bone with five fused segments. At the bottom of the sacrum is the coccyx (tail). When a person sits, she puts pressure on the sacrococcygeal junction. The sacrum translates the forces of the upper bodies to the legs via the sacroiliac joint. There is some degree of controversy as to the precise nature of the sacroiliac joint itself. Part of the sacroiliac joint contains cartilage and resembles a synovial joint. Part of the sacroiliac joint is a syndesmosis , which is a joining of two bones that does not satisfy the anatomic definition of a synovial joint. In the end, what can be said is that the sacroiliac joint is a tough, fibrous, stable joint that has some limited but important movement [5].

Intervertebral Discs

Between each lumbar vertebra , and between the L5 and the S1 bones, is an intervertebral disc (Fig. 1.3). It is helpful to think of the intervertebral disc as similar to a jelly donut. There is the inner jelly called the nucleus pulposus . The nucleus pulposus is composed of type II collagen and a mucoprotein gel with numerous proteins with pro-inflammatory properties [6]. The nucleus pulposus provides the cushioning of the disc [7]. The crust of the disc is called the annulus fibrosus . The annulus fibrosus is a tough, fibrous cartilage composed of type I collagen that provides the stability of the disc. In the outer third of the annulus fibrosus, and sometimes the outer 2/3 of the annulus fibrosus , there are sensory nerve fibers [8]. This is a particularly important fact when considering discogenic lower back pain in which a tear extends from the nucleus pulposus to the outer third or two thirds of the annulus fibrosus. This tear allows the proteins with inflammatory properties to reach the nerve fibers, which in turn are capable of causing pain [9]. This will naturally be discussed in detail in the chapter on discogenic lower back pain.