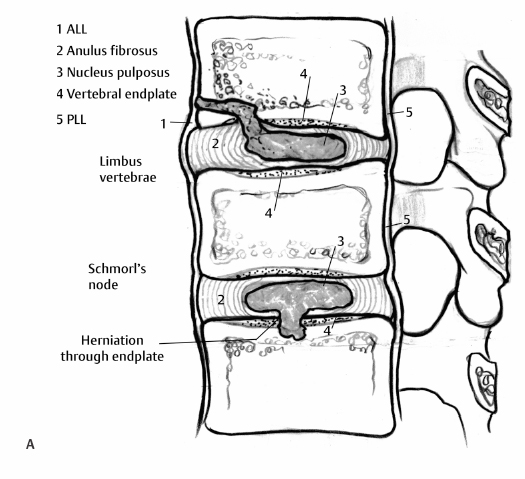

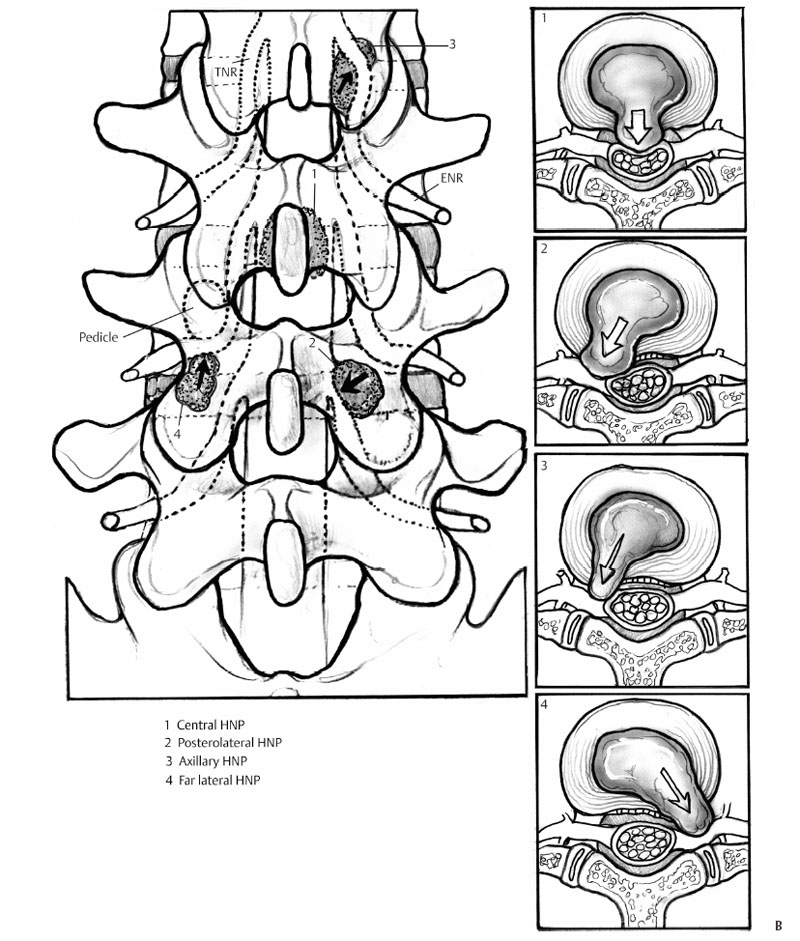

8 Clinical Features of Herniated Nucleus Pulposus Stewart M. Kerr, Deepan N. Patel and Alexander R. Vaccaro Intervertebral discs (IVDs) provide for a segmental arrangement to the spinal column which allows for movement and flexibility in what would otherwise be an immobile rigid column of bone. The IVD, like most connective tissue, consists of a sparse cell population. It is comprised of the outer and inner anulus fibrosus (AF) and a central gelatinous, semicompressible core—the nucleus pulposus (NP). These structures are composed largely of proteoglycans and the fibrillar collagens (type I and II), the ratio of which favors a preponderance of type II collagen with increasing proteoglycan concentration toward the disc center.1–5 With aging, the AF collagen fibers become more disorganized and also can harden; fissures can form within these fibers and occasionally extend full thickness. This may allow for protrusion of the inner, gelatinous nucleus pulposus. A herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) usually occurs in a posterior or posterolateral direction as a result of relative interface weakness between the outer AF, its vertebral body insertion, and the posterior longitudinal ligament. Herniated tissue frequently results in compression of neural or neurovascular structures potentially causing pain and neurologic dysfunction.6 In this chapter, we will review the risk factors and clinical features of herniated lumbar nucleus pulposus, which may include axial pain and a wide array of sensory-motor dysfunction. We additionally will discuss cauda equina syndrome (CES) and specific imaging modalities helpful in the evaluation of HNP. The predominance of posterior-lateral herniations (aside from the previously mentioned weak points in the anulus adjacent to the midline posterior longitudinal ligament [PLL]), may also result from circumferential variations in annular material properties; the anterior portions have both a larger tensile modulus of elasticity and ultimate stress.7 It is also likely that posterior herniations are more symptomatic than are anterior herniations and are therefore brought to clinical attention more frequently. In addition to posterior or posterolateral herniations, the nucleus pulposus may herniate into a far lateral position or through the endplates and into adjacent vertebral bodies (Schmorl’s node) (Fig. 8.1). Contained herniations occur when the NP remains trapped within the outer fibers of the AF and has not breached the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL).8 When the HNP extends through the AF, it is considered to be extruded and can be further classified as either a free fragment or sequestered.8 Rarely, the HNP may migrate intradurally (Fig. 8.2). Symptoms typically present when the extruded NP compresses neural tissue resulting in both a mechanical and cytokine-induced inflammatory effect frequently causing pain and dysfunction.9 True soft disc herniations most commonly occur in the third to fourth decades of life while the nucleus still has high water turgor.10 Skeletal biomechanics, occupation, and some lifestyle factors likely play a role in the development of an HNP. Symptomatic disc herniations are seen more commonly in men with exposure to prolonged vehicle or industrial vibrations and in those that engage in repetitive pulling or lifting work. Sagittal spine imbalance, pregnancy, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle have also been shown to contribute to the risk of disc herniation.11 The NP is capable of swelling to roughly 200% of its initial volume.12 Prolonged recumbency retards water egress from the NP and is associated with higher hydrostatic pressure and for some patients greater disc volumes. This explains why many disc herniations occur shortly after disc loading during the transition from a recumbent to upright posture.13 The clinical presentation of an HNP varies from no symptoms to rapid paralysis; the severity of symptoms often correlate with the acuity and degree of compression to the neural and vascular elements. In the lumbar spine, herniations are most common at L4-L5 and L5-S1. Common presenting features include radicular pain and numbness, dysesthesias, motor weakness, and even muscle atrophy from prolonged compression or disuse. The lumbar spine is the most common location for symptomatic disc herniations accounting for 80% of all disc herniations. Common symptoms of symptomatic lumbar disc herniations are varied and include lower back and buttock pain, with or without radicular leg pain and sensory dysesthesias. These symptoms may be partially relieved with rest, activity modification, or change in position. Trunk flexion, prolonged standing or sitting, and straining maneuvers (i.e., Valsalva, cough), commonly increase the symptoms of disc herniation.14 Manifestations of herniated discs range from progressive motor weakness to conditions adversely affecting bladder, bowel, and sexual function such as conus medullaris and cauda equina syndromes.15 Axial pain may result from a disc herniation at any level within the spine. The cause and effect relationship, however, is unclear. In some patients, prodromal pain is experienced before a disc herniates. On the other end of the spectrum, an estimated one-third of people do not develop pain or other symptoms in the presence of HNP. Pain subsides in over 90% of symptomatic patients within 12 weeks of presentation.16 The pain is presumed to result from both mechanical pressure and chemical inflammation of the nerve root by the HNP. Pain generation from disruption of the AF is thought to be mediated via branches of the sinuvertebral nerves as the posterior anulus and PLL are the most highly innervated structures in the functional spinal unit.6 Willburger and colleagues17 investigated the histologic composition of herniated fragments and found higher pain intensity values correlated with increased NP and cartilage percentages. However, the individual contributions to pain from direct pressure, chemical inflammation, the composition of herniated tissue and disrupted anulus are likely variable and remain unclear.8 Fortunately, most patients do not require operative management of lumbar HNPs.18 Radicular leg pain radiating below the knee is a helpful clinical pearl favoring the diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation. Classic lumbar NPH findings are shown in Table 8.1. Herniations typically result in impingement of the adjacent, traversing nerve root. In the setting of associated inflammation, the patient may develop discomfort in a dermatomal or radicular distribution.19 Far lateral herniations, unlike a posterolateral herniation, characteristically compress the exiting rather than the traversing nerve root (i.e., a far lateral L4-L5 HNP will compress the L4 not the L5 nerve root).9,20 An HNP at L4-L5 or L5-S1 is suggested by a positive straight-leg raise or tension test. This is performed by elevating the symptomatic straight leg in a supine patient or extending the flexed knee in a seated patient. A positive test occurs when the patient experiences below-the-knee pain in a dermatomal or myotomal distribution correlating with the anatomic location of the herniated disc. During the performance of this test in a seated patient, the patient may feel the need to slump or lean back and assume a tripod stance by balancing on their outstretched hands to relieve the pain. A positive contralateral straight-leg test occurs when straight-leg raising on the uninvolved side reproduces neural tension radicular pain in the opposite leg. Some clinicians anecdotally assume that a contralateral straight-leg test is often pathognomonic for the presence of a clinically significant disc herniation. However, the accuracy of the straight-leg and contralateral straight-leg tests in diagnosing a clinically significant HNP are limited by low specificity. Meta-analysis studies report sensitivity/specificity values of 0.85/0.52 and 0.30/0.84 for the straight-leg test and cross straight-leg tests, respectively.21 The tension maneuver for an upper lumbar disc herniation involves the femoral nerve stretch test.22 This is performed by extending the hip on the symptomatic side with the knee in the flexed position performed with the patient standing or in the prone position.

Types of Nucleus Pulposus Herniation

Herniation Risk Factors

Clinical Features of a Herniated Nucleus Pulposus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree