SECTION III CLINICAL PRESENTATION, ANATOMICAL CONCEPTS AND DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

HEADACHE – GENERAL PRINCIPLES

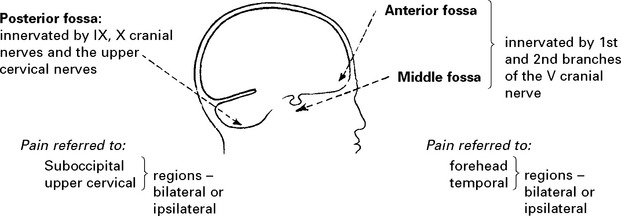

Intracranial pain-sensitive structures are:

venous sinuses, cortical veins, basal arteries, dura of anterior, middle and posterior fossae.

Extracranial pain-sensitive structures are:

Estimated prevalence of headache in the general population

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Tension type headache | 50–70 |

| Migraine | 10–15 |

| Medication overuse headache | 4 |

| Cluster headache | 0.1 |

| Raised intracranial pressure | < 0.01 |

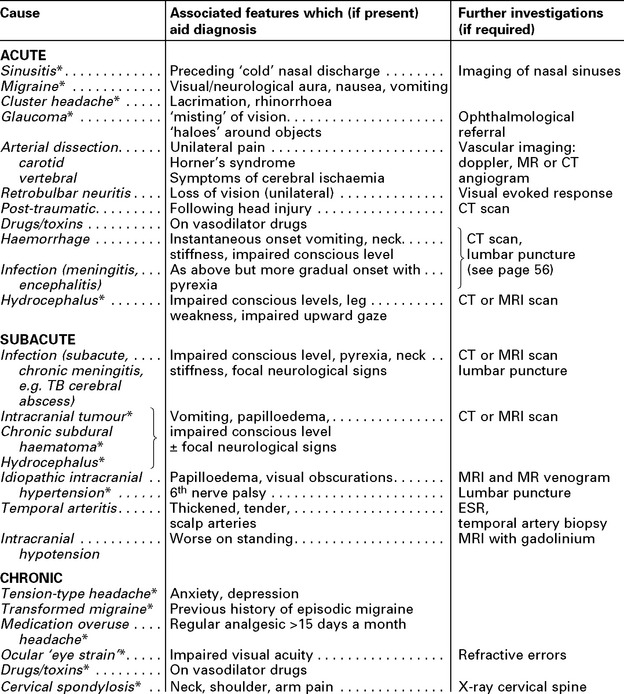

HEADACHE – DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

History: most information is derived from determining:

The following table classifies causes in these categories:

(*) Indicates that attacks can be recurrent

HEADACHE – SPECIFIC CAUSES

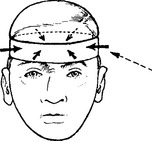

TENSION TYPE HEADACHE

Frequency: Infrequent or daily; worse towards the end of the day. May persist over many years.

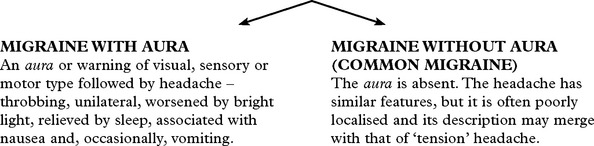

MIGRAINE

Migraine is a common, often familial disorder characterised by unilateral throbbing headache.

Onset: Childhood or early adult life.

Incidence: Affects 5–10% of the population.

Family history: Obtained in 70% of all sufferers.

Specific diagnostic criteria are required for migraine with and without aura.

Management

POST-TRAUMATIC HEADACHE

CLUSTER HEADACHES (Histamine cephalgia or migrainous neuralgia)

Other Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalagias

GIANT CELL (TEMPORAL) ARTERITIS

Neurological symptoms: strokes, hearing loss, myelopathy and neuropathy.

Visual symptoms are common with blindness (transient or permanent) or diplopia.

Duration: the headache is intractable, lasting until treated.

HEADACHE FROM RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

| Characteristics: | Associated features: |

|---|---|

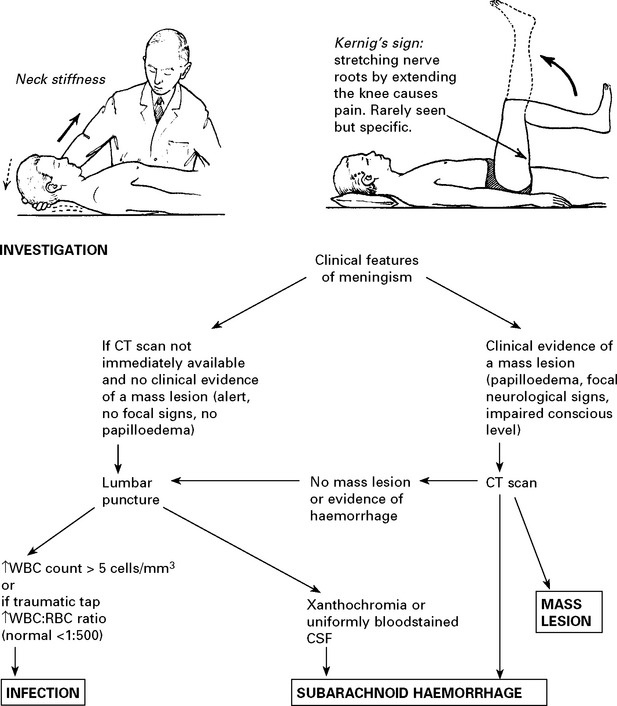

HEADACHE DUE TO INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE

Management: further investigation – CT scan/lumbar puncture (see Meningism, page 75).

N.B. Consider sudden severe headaches to be due to subarachnoid haemorrhage until proved otherwise.

NON-NEUROLOGICAL CAUSES OF HEADACHE

Sinuses: Well localised. Worse in morning. Affected by posture, e.g. bending.

X-ray – sinus opacified. Treatment – decongestants or drainage.

Ocular: Refraction errors may result in ‘muscle contraction’ headaches

– resolves when corrected with glasses.

Dental disease: Discomfort localised to teeth. Check for malocclusion.

Check temporomandibular joints.

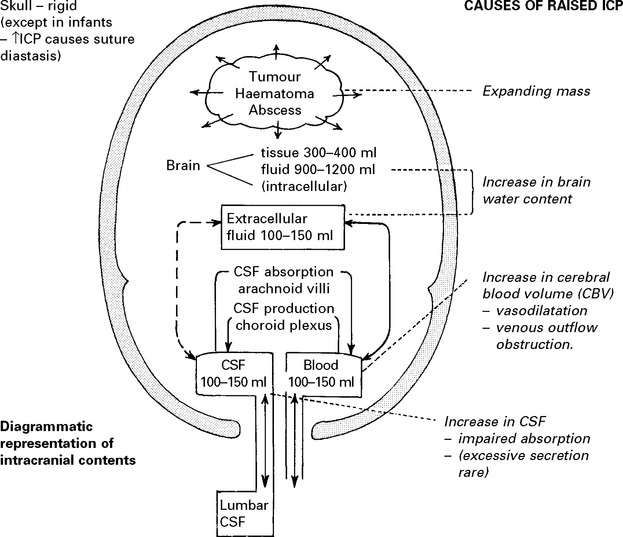

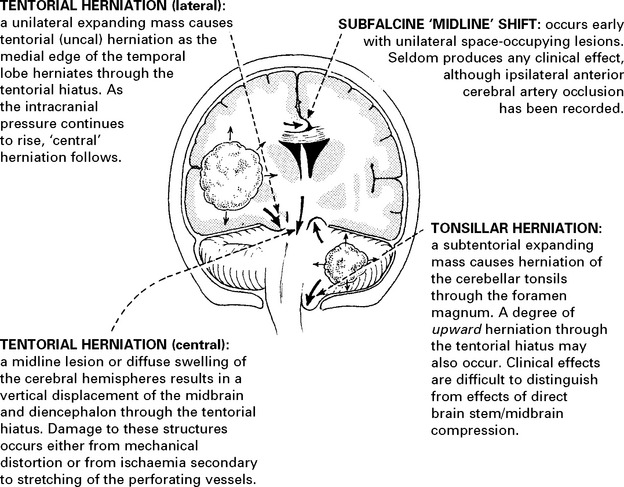

RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

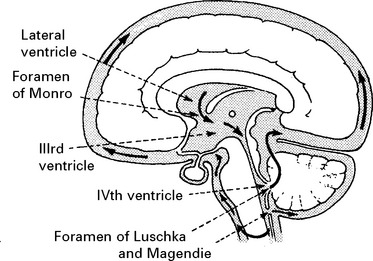

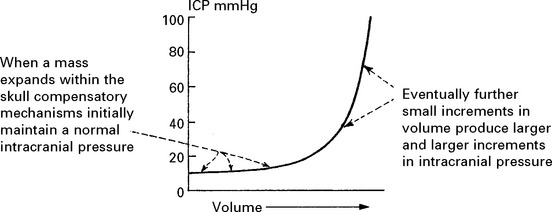

Compensatory mechanisms for an expanding intracranial mass lesion:

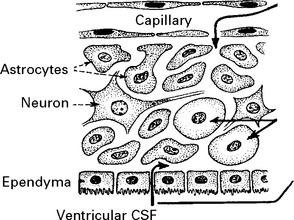

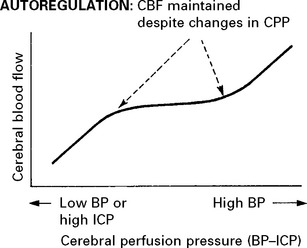

CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW (CBF)/CEREBRAL BLOOD VOLUME (CBV)

Blood flow is dependent on blood pressure and the vascular resistance:

Inside the skull, intracranial pressure must be taken into account:

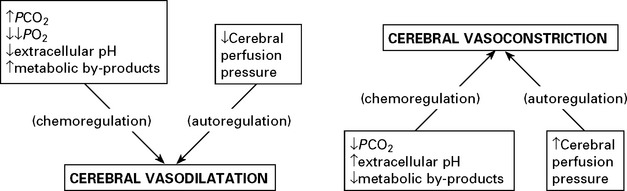

FACTORS AFFECTING THE CEREBRAL VASCULATURE

Chemoregulation

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE (ICP)

When intracranial pressure is monitored with a ventricular catheter, regular waves due to pulse and respiratory effects are recorded (page 53). As an intracranial mass expands and as the compensatory reserves diminish, transient pressure elevations (pressure waves) are superimposed. These become more frequent and more prominent as the mean pressure rises.

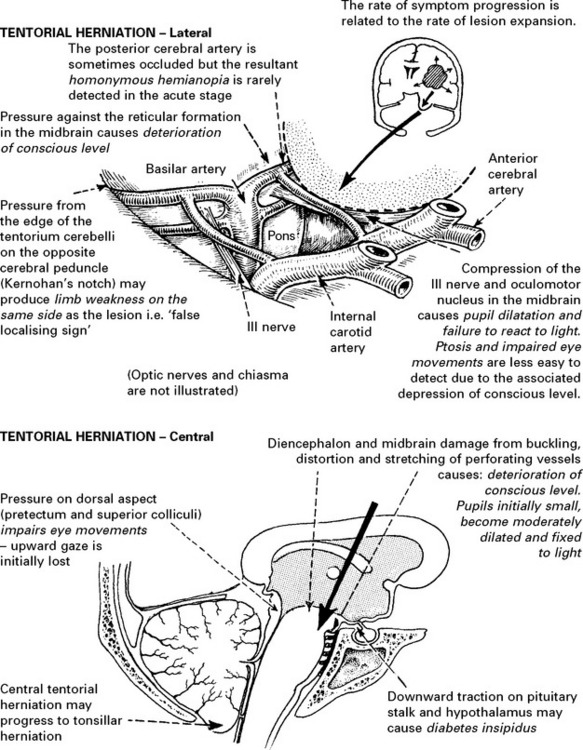

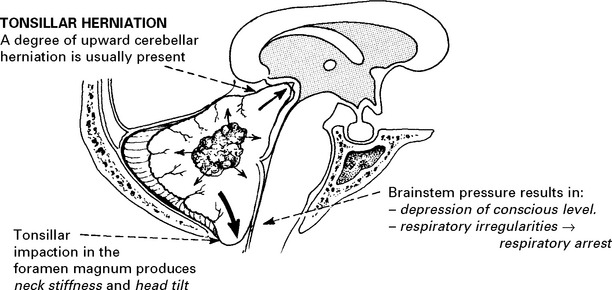

CLINICAL EFFECTS OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Clinical features due to ↑ICP:

INVESTIGATIONS

Patients with suspected raised intracranial pressure require an urgent CT/MRI scan. Intracranial pressure monitoring where appropriate (see page 53).

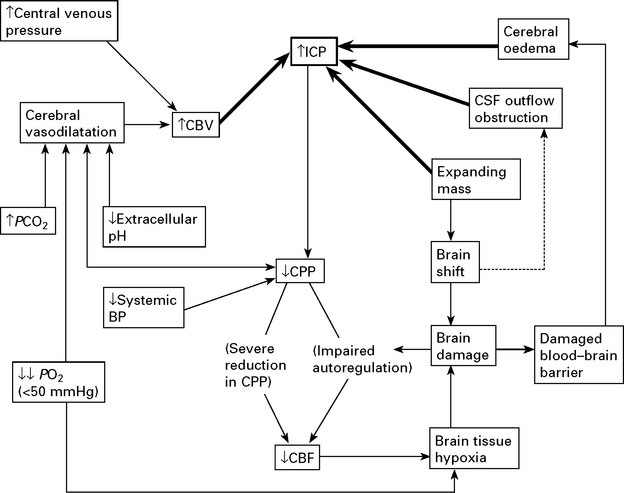

TREATMENT OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

In some patients, despite the above measures, cerebral swelling may produce a marked increase in intracranial pressure. This may follow removal of a tumour or haematoma or may complicate a diffuse head injury. Artificial methods of lowering intracranial pressure may prevent brain damage and death from brain shift, but some methods lead to reduced cerebral blood flow, which in itself may cause brain damage (see page 84).

Intracranial pressure is monitored with a ventricular catheter or surface pressure recording device (see page 52). Treatment may be instituted when the mean ICP is > 25 mmHg. Ensure cause is not due to constriction of neck veins.

Methods of reducing intracranial pressure

Controlled hyperventilation: Bringing the PCO2 down to 3.5kPa by hyperventilating the sedated or paralysed patient causes vasoconstriction. Although this reduces intracranial pressure, the resultant reduction in cerebral blood flow may aggravate ischaemic brain damage and do more harm than good (see page 232). Maintaining the blood pressure and the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) (>60 mmHg) appears to be as important as lowering intracranial pressure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree