chapter 1

Clinically Oriented Neuroanatomy

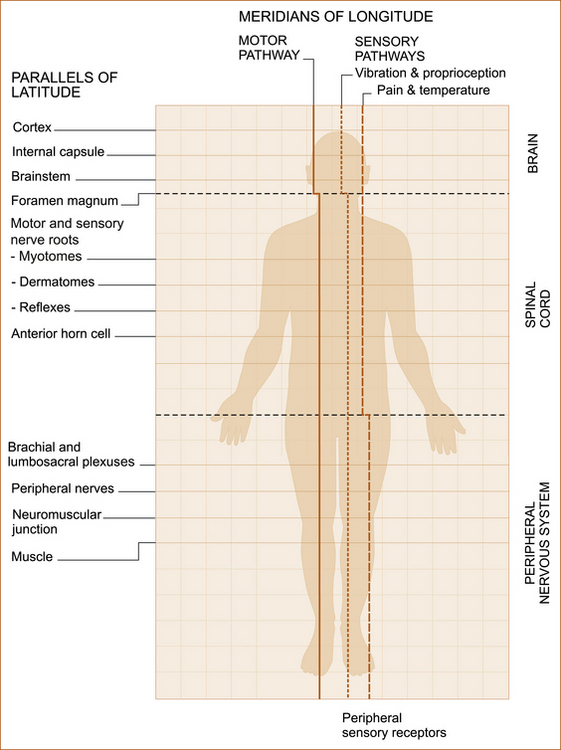

‘MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE AND PARALLELS OF LATITUDE’

Although most textbooks on clinical neurology begin with a chapter on history taking, there is a very good reason for placing neuroanatomy as the initial chapter. It is because clinical neurologists use their detailed knowledge of neuroanatomy not only when examining a patient but also when obtaining a neurological history in order to determine the site of the problem within the nervous system. This chapter not only describes the neuroanatomy but attempts to place it in a clinical context.

The ‘student of neurology’ cannot be expected to remember all of the detail but needs to understand the basic concepts. This understanding, combined with the correct technique when taking the neurological history (see Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’) and performing the neurological examination (see Chapter 3, ‘Neurological examination of the limbs’, Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’, and Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’), together with the illustrations in this chapter will enable the ‘non-neurologist’ to localise the site of the problem in most patients almost as well as the neurologist. It is intended that this chapter serve as a resource to be kept on the desk or next to the examination couch.

to disorders of the PNS, the anterior horn cell, motor nerve root, brachial or lumbrosacral plexus or peripheral nerve (see Table 1.1). The alterations in strength, tone, reflexes and plantar responses (scratching the lateral aspect of the sole of the foot to see which way the big toe points) are different in upper and lower motor neuron problems.

TABLE 1.1

Upper and lower motor neuron signs

| Upper motor neuron signs | Lower motor neuron signs | |

| Weakness | The UMN pattern∗ | Specific to a nerve or nerve root |

| Tone | Increased | Decreased |

| Reflexes | Increased | Decreased or absent |

| Plantar response | Up-going | Down-going |

∗The muscles that abduct the shoulder joint and extend the elbow and wrist joints are weak in the arms while the muscles that flex the hip and knee joints and the muscles that dorsiflex the ankle joint (bend the foot upwards) are weak in the legs.

The reason why this is so important is highlighted in Case 1.1.

CONCEPT OF THE MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE AND PARALLELS OF LATITUDE

• The descending motor pathway from the cortex to the muscle

• The ascending sensory pathway for pain and temperature

• The ascending sensory pathway for vibration and proprioception

The ascending sensory pathways extend from the peripheral nerves to the cortex.1

The parallels of latitude

• Weakness + marked wasting – the peripheral nervous system, as marked wasting does not occur with central nervous system problems

• Weakness + cranial nerve involvement – brainstem

• Weakness + visual field disturbance (not diplopia) or speech disturbance (i.e. dysphasia) – cortex

• Weakness in both legs + loss of pain and temperature sensation on the torso – spinal cord

• Weakness in a limb + sensory loss in a single nerve (mononeuritis) or nerve root (radiculopathy) distribution – peripheral nervous system

THE MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE: LOCALISING THE PROBLEM ACCORDING TO THE DESCENDING MOTOR AND ASCENDING SENSORY PATHWAYS

Cases 1.2 and 1.3 illustrate how to use the meridians of longitude.

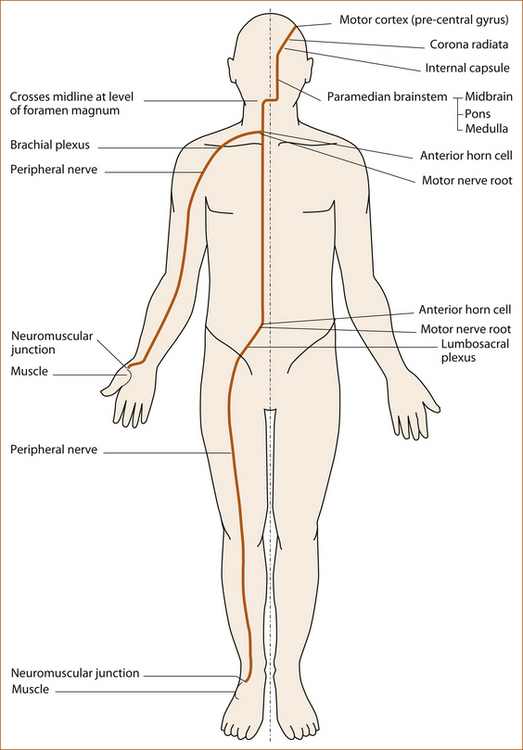

The motor pathway

The motor pathway (see Figure 1.2) refers to the corticospinal tract within the central nervous system that descends from the motor cortex to lower motor neurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and the corticobulbar tract that descends from the motor cortex to several cranial nerve nuclei in the pons and medulla that innervate muscles plus the motor nerve roots, plexuses, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junction and muscle in the peripheral nervous system.

• arises in the motor cortex in the pre-central gyrus (see Figure 1.5) of the frontal lobe

• descends in the cerebral hemispheres through the corona radiata and internal capsule

• passes into the brainstem via the crus cerebri (level of midbrain) and descends in the ventral and medial aspect of the pons and medulla

• descends in the lateral column of the spinal cord to the anterior horn cell where it synapses with the lower motor neuron

• leaves the spinal cord through the anterior (motor) nerve root

• passes through the brachial plexus to the arm or through the lumbosacral plexus to the leg and via the peripheral nerves to the neuromuscular junction and muscle.

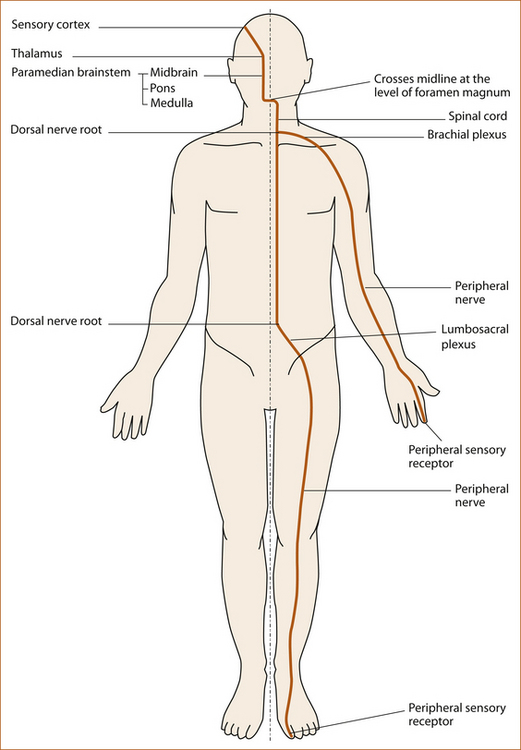

The sensory pathways

PROPRIOCEPTION AND VIBRATION

• arises in the peripheral sensory receptors in the joint capsules and surrounding ligaments and tendons (proprioception) or in the pacinian corpuscles in the subcutaneous tissue (vibration) [1]

• ascends up the limb in the peripheral nerves

• traverses the brachial or lumbosacral plexus

• enters the spinal cord through the dorsal (sensory) nerve root

• ascends in the ipsilateral dorsal column of the spinal cord with the sacral fibres most medially and the cervical fibres lateral

• ascends in the medial lemniscus in the medial aspect of the brainstem via the thalamus to the sensory cortex in the parietal lobe.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree