Assessment interview

Table 6.3.2.1.3 summarizes the main topics covered in the assessment interview. The aims of the interview are as follows: (a) to obtain a detailed description of the patient’s fears and behaviour; (b) to identify maintaining factors; (c) to normalize the problem; (d) to develop a model of the problem that can be used to guide treatment.

The interview would start by asking the patient to provide a brief description of the main presenting problem(s). For example, intense anxiety attacks, anxious apprehension, and avoidance of places where the attacks seem particularly likely or would be embarrassing. The interviewer then obtains a detailed description of a recent occasion when the problem occurred or was at its most marked. This would include the situation (‘Where were you?’, ‘What were you doing?’), bodily reactions (‘What did you notice in your body?’, ‘What sensations did you experience?’), thoughts (‘At the moment you were feeling particularly anxious, what went through your mind? What was the worst that you thought might happen? Did you have an image/mental picture of that? How do you think you looked?’), behaviour (‘What did you do?’), and the behaviour of others (‘How did X react?’, ‘What did X say/do?’). Having obtained a detailed description of a recent occasion, the interviewer should check whether the occasion was typical. If not, further descriptions of other recent occasions should be elicited to provide a complete picture.

Next a list of situations in which the problem is most likely to occur or is most severe is elicited (‘Are there any situations in which you are particularly likely to have a panic attack?’), together with information about modulators (‘Are there any things that you notice make the symptoms stronger/more likely to occur?’, ‘Are there any things that you’ve noticed make the symptoms less likely/ less severe/more controllable?’).

Possible maintaining factors should be identified, including the following:

avoidance of situations or activities (‘What situations/activities do you avoid because of your fears?’)

safety behaviours (‘When you are afraid that X might happen, is there anything you do to try to stop it happening?’)

attentional deployment (‘What happens to your attention when you are worried about X? Do you focus more on your body? Do you become self-conscious?’)

faulty beliefs (e.g. an obsessive-compulsive disorder patient, believing that thinking something can make it happen)

attitudes and behaviour of significant others (‘What does Y think about the problem?’; ‘What does Y do when you are particularly anxious?’)

current medication

There are several ways in which excessive use of both prescribed and non-prescribed medications can maintain anxiety disorders. For example, painkillers and tranquillizers can cause derealization and sleep disturbance respectively, and drinking before social occasions prevents disconfirmation of one’s social fears.

It is also important to assess patients’ beliefs about the cause of their problems as some beliefs may make it difficult for patients to engage in therapy. For example, patients with post-traumatic stress disorder who think the best way of dealing with a painful memory is to push it out of their mind are unlikely to engage in imaginal reliving of the event until this belief is dealt with.

Finally, a brief description of the onset and subsequent course of the problem should be obtained. This description should particularly focus on factors, which may have been responsible for initial onset and for fluctuations in the course of the symptoms and is primarily used to make the development of the problem seem understandable to the patient.

It is not always possible to obtain all the information needed for a cognitive behavioural formulation in an assessment interview. Sometimes it is necessary to follow-up the interview with homework assignments in which the patient collects more information to clarify the formulation. For example, a hypochondriacal patient who was concerned that palpitations meant that she had cardiac disease was asked to record what she did each hour and how many palpitations she experienced. To her surprise, palpitations were not associated with exercise, as she expected, but rather were most common when she was sitting quietly, reading, watching television, or studying. This realization helped convince her that her problem may be disease preoccupation rather than a faulty heart.

Developing an idiosyncratic model of the patient’s problem

Assessment ends with the development of an idiosyncratic version of the cognitive model. In particular, therapists aim to show patients

how the specific triggers for their anxiety produce negative automatic thoughts relating to feared outcomes and how these are maintained by safety behaviours and other maintenance processes. The model is usually drawn on a whiteboard, so that patient and therapist can look at it and discuss it together.

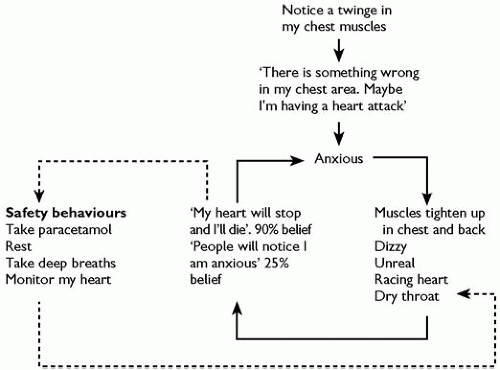

Figure 6.3.2.1.1 shows an example for a panic disorder patient. His panic attack started with a twinge in his chest muscles, and he then had the thought, ‘There is something wrong with my chest area, maybe I am having a heart attack’. This interpretation made him start to feel anxious, his chest muscles tightened up more, he started to feel dizzy, his heart raced more, and he then thought, ‘I’m dying, I’m having a heart attack’, and also, interestingly, ‘If I don’t die, people will notice I’m anxious and think it is odd’. He then engaged in a series of safety behaviours to try to prevent himself from dying. He thought he had read somewhere that paracetamol (aminacetophen) is good for people with heart problems and so he took a paracetamol. This is incorrect information, but the key point is that he believed it. He also sat down and rested, took the strain off his heart, and took deep breaths, trying to slow down his heart rate. He believed that the main reason he had not died was that he had engaged in the safety behaviours. The reader will also notice that some of the safety behaviours (taking deep breaths and monitoring the heart) will also have augmented his feared symptoms.

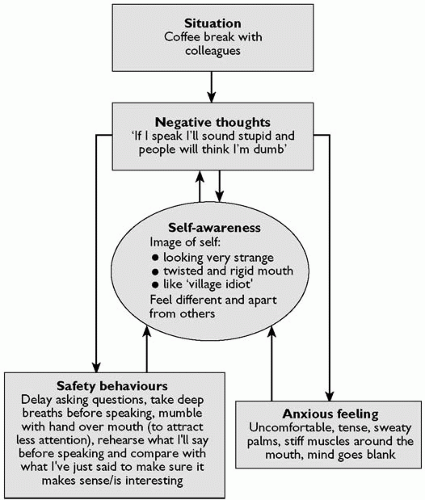

Figure 6.3.2.1.2 shows a further example with a social phobic patient. The patient’s main fear was that other people would think she was stupid and boring. The situation used to develop the model was a recent coffee break at work during which the patient had difficulty joining a conversation with colleagues. When attempting to join the conversation she had the thought, ‘I’ll sound stupid and everyone will think I am dumb’. In order to prevent herself from sounding stupid, she engaged in an extensive set of safety behaviours which (a) prevented her from discovering that her spontaneous thoughts are interesting to other people, (b) made her appear preoccupied and uninterested in her colleagues, and (c) made her excessively self-conscious. While self-conscious, she became particularly aware of anxiety symptoms (sweaty palms, stiff muscles around her mouth) that she thought other people might see, and indeed, had an image of herself in which she looked very strange, with a twisted and rigid mouth and appeared stupid.

Normally idiosyncratic models of the form illustrated in

Figs 6.3.2.1.1 and

6.3.2.1.2 will be developed at the end of the first interview, and certainly not later than the second session. Such models are used as blueprints to help therapist and patient organize and develop the rest of therapy.

Treatment procedures

A wide range of procedures can be used to modify patients’ negative beliefs and linked maintenance processes. For clarity the procedures are described separately. However, in practice the techniques are closely interwoven. Within a given session, therapists will usually use a mixture of discussion and experiential techniques to help patients to challenge convincingly their negative beliefs. As with cognitive behaviour therapy for other disorders, patients are given extensive homework assignments and it is assumed that a sizeable amount of therapeutic change is the result of homework assignments.

(a) Identifying patients’ evidence for their negative beliefs

Anxiety disorder patients usually have reasons for believing that the things they fear are dangerous, however strange their fears may seem. The therapist, therefore, tries to ‘get inside the patient’s head’ and see what the evidence is. Often the evidence is an event or piece of information that the patient has misinterpreted. Identifying and correcting such misinterpretations can be helpful. For example, a panic disorder patient believed that experiencing high anxiety could kill her. When asked by the therapist what her evidence was, she explained that she had seen it happen. Further enquiry revealed she had entered Dresden the day after the fire bombing of that city by the allies during the Second World War and had helped search for survivors. When opening up cellars below demolished houses, she repeatedly observed that the occupants were either dead or behaved in a dazed confused manner, even though the fire had not entered their cellars. She concluded that fear had killed the occupants or sent them mad. However, further questioning from the therapist revealed that the cellar occupants all had bright cherryred lips. This allowed the therapist to explain that they were suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning, not the effects of intense fear. This correction considerably reduced the patient’s fear of anxiety.

(b) Education

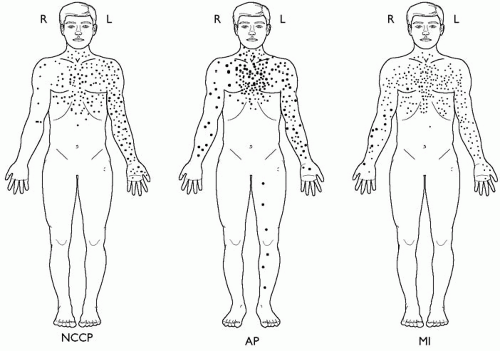

Education about the symptoms of anxiety is often helpful, especially if it directly targets patients’ idiosyncratic fears and concerns. For example, post-traumatic stress disorder patients often think their flashbacks and emotional outbursts mean they are going mad or have permanently changed for the worse. In such cases, detailed assessment of the patient’s post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and explanation that each are common reactions to a trauma can greatly help. Similarly, panic disorder patients with cardiac concerns often cite left-sided chest pain as evidence for their belief that they have a cardiac disorder. In such cases discussion of

Fig. 6.3.2.1.3 (from a study of chest pain in patients referred to a cardiac clinic

(26)) is useful. In particular, the patient discovers that left-sided chest pain is more characteristic of non-cardiac chest pain than of either confirmed angina or myocardial infarction. Further questioning helps patients to see that the association between left-sided pain and attacks is probably a consequence of their fears. That is to say, they can experience pain on either side of the chest but only panic when it is on the left side. Finally, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who are perturbed by the apparently repulsive and unusual nature of their intrusive thoughts often benefit from reviewing Rachman and De Silva’s classic

paper

(10) which demonstrated that thoughts with identical content to obsessional intrusions are common in the general population.

(c) Identifying observations that contradict patients’ negative beliefs

As anxiety disorder patients’ beliefs about the dangerousness of feared stimuli are generally mistaken, patients have often experienced a number of events that contradict their beliefs before they come into therapy. Therapists can make considerable progress, even in an assessment interview, by spotting these events and helping patients understand their significance. For example, panic disorder patients who are worried that their symptoms mean they are about to have a heart attack, often report that in some attacks something unexpected happened to distract them (e.g. a telephone call) and then their symptoms went away. Therapists could then pause and help the patient understand what this means, perhaps asking, ‘Would a cardiologist prescribe telephone calls as a treatment for a heart attack?’ The patient would probably answer ‘No’, to which the therapist might reply, ‘If telephone calls would not stop a heart attack, how might they work? If the problem was the negative thought, could they help (by distracting one from the thoughts)?’

(d) Imagery modification

Images play an important role in many anxiety disorders. Most images represent feared catastrophes and can be treated as predictions to be tested (see behavioural experiments below). However, when the images are stereotyped and repetitive it is often also necessary to work directly with the images and to restructure them explicitly.

The problem with anxiety-related images is that they seem very realistic at the time they occur and, as a consequence, greatly enhance fear. A common restructuring technique involves discussing with the patient whether the image is realistic. Once it is intellectually agreed that the image is an exaggeration, patients are asked to recreate intentionally the negative image and to hold it in mind until they start to feel anxious. They are then asked to transform it into a more realistic image, or an image, which convincingly indicates that the original image was unrealistic. A common observation is that patients’ spontaneous images generally stop at the worst moment. For example, agoraphobic patients who fear fainting in a supermarket might see themselves collapsed on the floor, but not see themselves getting up, recovering, and going home. A useful transformation in such cases is to ‘finish out’ the image by asking patients to run it on until they see the positive resolution. Of course, sometimes simply running on an image does not produce a positive resolution. For example, a patient who feared she would go mad frequently experienced an image of two men in white coats entering her house to take her away to a locked ward. In the image, the men were extremely powerful and she felt powerless. Transformation, following suggestions from her, involved shrinking the men and then turning them into ridiculous looking (and hence non-threatening) white poodles.

An interesting observation about spontaneous imagery is that it often fails to incorporate positive information that would seriously undermine the impact of the image, even when the patient has such information. For example, a mother whose children died in a house fire, repeatedly experienced intrusive flashbacks in which she saw the house going up in flames and smelled burning flesh, despite having seen her children in the mortuary, knowing that they had not been burnt, but instead were rapidly overcome by fumes.

For imagery restructuring to be effective it is important that it is not done as a cold, intellectual exercise, but instead includes eliciting the affect normally associated with the image. Transformation may have to be done in several steps. It is often best to start with the

most threatening aspect of the image. Possible alternative images should be generated by patients, rather than simply imposed by the therapist.

(e) Cognitive restructuring

All the above techniques are examples of cognitive restructuring in which the therapist provides information and asks a series of questions to help the patients challenge their fearful thoughts and images. A list of some of the questions that can be particularly useful for helping anxiety disorder patients challenge their negative thoughts is given in

Table 6.3.2.1.5. Further useful questioning techniques can be found in

Chapter 6.3.2.3.

It is sometimes helpful to use graphical methods for discussing alternatives to negative thoughts. In situations where there are several non-threatening alternative explanations for a feared event, pie charts are particularly useful. When constructing a pie chart the therapist draws a circle which is meant to represent all the possible causes of a particular event and asks the patient to list all the possible non-catastrophic causes of the event and allocate a section of the circle to each cause. At the end of the exercise, there is often very little of the circle left for the patient’s negative explanations.

Figure 6.3.2.1.4 illustrates the use of a pie chart to challenge a generalized anxiety disorder patient’s belief that he would be 100 per cent responsible for people not enjoying themselves at his dinner parties. The belief was preventing him from making new social contacts after a painful divorce. Pie charts are particularly helpful for dealing with distorted beliefs about responsibility and hypochondriacal concerns (e.g. ‘Headaches mean I have a brain tumour’).

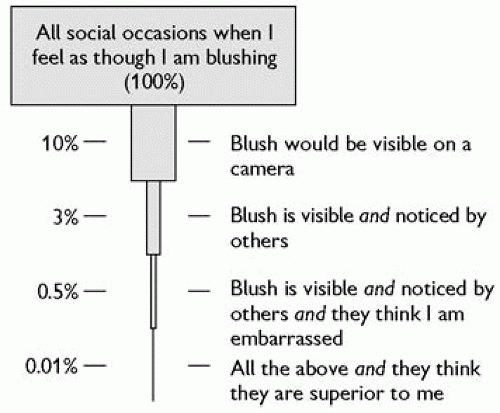

When considering the worst that could possibly happen in a feared situation patients frequently ignore the fact that there are many intermediate events, each with a probability of less than 1, which have to occur for the catastrophe to be realized. The inverted pyramid can be a good way of representing this.

Figure 6.3.2.1.5 shows an example with a patient who was afraid of blushing. His worst fear was that other people would think they were greatly superior to him if he blushed. Whenever he felt his face becoming hot, he was convinced other people were thinking they are superior to him and gloating. However, careful discussion helped him to see that there were many intermediate steps between him feeling hot and the feared outcome. Once the conditional probabilities were taken into account, there was only a minute chance that his worst fear would be correct.

It is important to remember that anxiety results from overestimating the cost of feared events as well as their probability. Discussions aimed at modifying perceived cost are often helpful. This can be true even in cases where it might seem obvious that the feared event is objectively costly. For example, in hypochondriacal patients who are worried about dying, therapists may be tempted to focus exclusively on whether or not the patients are likely to die from the symptoms they are concerned about. Accepting that dying is a bad thing, the therapist may not be inclined to ask, ‘What would be so bad about dying?’ However, Wells and Hackmann

(27) found that many hypochondriacal patients have distorted beliefs and images about death and the process of dying. For example, they think that when they die they will remain conscious and will continue to experience all the pain they had up to that point. Such people can benefit greatly from discussion of their beliefs about the cost of dying.

(f) In vivo exposure to feared situations, activities, and sensations

Systematic exposure to feared and avoided situations has a long history in cognitive behaviour therapy and is one of the most effective ways of helping patients to discover that the things they are afraid of will not happen or are more manageable than they anticipate. Initially, exposure was often conducted in imagination but it is now known that

in vivo exposure is a more effective way of dealing with situational fear.

(3) During the 1970s and 1980s the dominant framework for exposure was habituation. It was assumed that repeated prolonged exposure was required to achieve fear reduction. More recent cognitive formulations have suggested that exposure is likely to be optimally effective when set-up in a way that maximizes the extent to which patients are able to disconfirm their fears, and considerable attention is now devoted to setting up exposure assignments in a way that will maximize cognitive change. Before entering a feared situation, patients are asked to specify what is the worst they think could happen, how likely they think it is, and what they would normally do to prevent the feared catastrophe (safety behaviours). They are then asked to enter the feared situation while dropping their safety behaviours and to observe carefully whether the feared outcome occurs. Afterwards, discussion focuses on whether the feared catastrophe occurred. If it did not, how does the patient explain its non-occurrence? Was it because the patient now thinks the feared outcome is unrealistic or does the patient think it was because of ‘luck’ or the continued use of safety behaviours? In the latter two instances, further exposure assignments with further encouragement to drop safety behaviours are required.

In addition to avoiding feared situations, anxiety disorder patients can also avoid feared sensations. Such avoidance is particularly prominent in panic disorder. For example, because of their fears about the meaning of increases in heart rate, dizziness, sweating, and other autonomic cues, panic disorder patients often avoid exercise. Increasing exercise can be an excellent way of helping them to challenge their negative beliefs, as can other ways of inducing bodily sensations such as ingesting caffeine, and hyperventilating. In each instance, the key point is to help patients discover that they can experience intense physical sensations without dying, losing control, or experiencing some other catastrophe.

Table 6.3.2.1.6 shows a record sheet that can be useful for planning and summarizing the results of exposure assignments, with illustrations from patients with social phobia and agoraphobia. Because of the intensity of patients’ fears, and their tendency to attribute good outcomes to ‘luck’, it is often necessary to move up a hierarchy of feared situations and to consolidate successes by repetition.

In obsessive-compulsive disorder, the compulsive rituals act as safety behaviours and it is necessary to ensure that patients refrain from engaging in rituals (which are often also termed ‘putting right’ acts) during exposure assignments. This procedure is called ‘exposure and response prevention’. For example, obsessional washers would be asked to ‘contaminate’ themselves by touching feared objects and then not put things right by washing. Similarly, obsessional checkers may be asked to expose themselves to activities that would normally provoke their checking (e.g. turning on the gas cooker) and then refrain from checking more than would be normal. In both instances, patients usually find that although exposure initially provokes considerable distress, the distress systematically declines during prolonged response prevention.

(28)Unlike most phobic fears, the fears of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients (e.g. developing a fatal disease from touching an object that is believed to be contaminated) often cannot be discon-firmed during a single or indeed multiple, exposure assignments. Discussing this issue, Salkovskis

(11) has suggested that exposure and response prevention may work by providing patients with a different understanding of their problems. In particular, the decline

in distress during exposure and response prevention helps the patient to discover that they are suffering from a worry problem, rather than being in objective danger.

(g) Imaginal exposure in post-traumatic stress disorder

Although imaginal exposure is rarely used in most anxiety disorders, it plays an important role in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. It is known

(29) that avoidance of thinking about the traumatic event is an important predictor of persistent posttraumatic stress disorder. In the light of this finding, clinicians have attempted to treat post-traumatic stress disorder by repeated, imaginal reliving of the traumatic event, and controlled trials

(30) have shown that this technique is effective. At this stage it is not known why reliving works. One suggestion is that the intrusive symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder are the result of a fragmented and disorganized memory for the trauma that is poorly integrated with other autobiographical information. Reliving might, therefore, facilitate the production of a more organized narrative account of the event that can be placed in the broader context of the individual’s life.

(13,31) Two types of imaginal reliving have been used in controlled trials: writing out details of the event and reliving the event in imagery. In either case, it seems important to focus not only on what happened, but also on patients’ feelings and thoughts, both at the time and now, looking back at the event. Problematic idiosyncratic meanings that can be addressed with cognitive restructuring are often identified during reliving exercises.

(h) Behavioural experiments

Behavioural experiments play a central role in the treatment of anxiety disorders. In a behavioural experiment, therapist and patient plan and implement a behavioural assignment that will provide a test of a key belief. The in vivo exposure assignments outlined above are examples of behavioural experiments. Several further examples are given to illustrate the technique.

Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder often think their intrusive recollections mean they are going mad or losing control in some way, and as a consequence, try to push the intrusions out of their mind. If this problem is identified during the first session of therapy, therapists often conduct an experiment to illustrate the undesired consequences of thought suppression. For example, the therapist might say to the patient, ‘It doesn’t matter what you think about in the next few minutes as long as you don’t think about one particular thing. The thing is a fluorescent green rabbit eating my hair!’ Most patients find they immediately get an image of the rabbit and have difficulty getting rid of it. Discussion then helps them to see that an increase in the frequency of target thoughts is a normal consequence of thought suppression. This result can then be used to set-up a homework assignment in which the patient is asked to collect data to test the idea that thought suppression may be enhancing intrusions. The experiment involves not trying to push the intrusions out of one’s mind, but instead just letting them come and go, watching them as though they were a train passing through a station. Often patients report this simple experiment produces a marked decline in both the frequency of intrusions and the belief that they are a sign of impending insanity or loss of control.

Patients with social phobia often overestimate the significance of their anxiety symptoms for other people. A useful behavioural experiment to illustrate this point involves having either the patient or the therapist conduct a survey in which other people are asked for their views about the feared symptom. For example, in the case of fear of blushing, other people might be asked:

Why do you think people blush?

Do you notice other people blushing?

Do you remember it?

Do you think badly about people who blush?

If you do, what do you think about them?’

A further helpful experiment can involve intentionally displaying a feared symptom (e.g. handshaking or forgetting what one is talking about) and closely observing other people’s responses. A particularly effective behaviour experiment for modifying social phobics distorted self-images involves the use of video feedback. Patients are asked to engage in a difficult social task while being videotaped. Afterwards they are asked to describe in detail how they think they appeared. They are then asked to view the video, watching themselves as though they are watching a stranger, ignoring memories of how they felt and simply focusing on how they would look to other people. In this way they often discover that they come across better than they would expect on the basis of their self-imagery. This experiment is often a powerful way of correcting distorted self-images.

Patients with panic disorder or hypochondriasis persistently think that normal bodily signs and/or symptoms are caused by a serious physical disorder. Numerous behavioural experiments can be used to demonstrate the correct, innocuous causes of their symptoms. For example, reading pairs of words which represent patient’s illness interpretations (e.g. palpitations-dying, breathlessness-suffocate) has been shown to induce feared sensations.

(5) Similarly, reproducing patients’ fear-driven behaviours can produce the very symptoms the patients take as evidence for a serious physical illness. For example, patients who feel short of breath in a panic attack often respond by breathing quickly and deeply (hyperventilation), which paradoxically produces more breathlessness. Similarly, patients who are concerned about cancer may palpate body parts and then take the resulting soreness or discomfort as evidence of the presence of cancer.

(i) Therapy notes

Over a series of sessions therapist and patient will generate a substantial number of arguments against the patient’s fearful beliefs. In order to maximize the impact of this accumulation, patients are asked to keep a running record of evidence against their beliefs in a notebook that can easily be consulted at times of doubt.

Table 6.3.2.1.7 shows an illustrative example from a panic disorder patient’s notebook. At the start of therapy, the patient had been concerned that there was something seriously wrong with his heart.

(j) Anger management

Although anxiety is the predominant problematic emotion in anxiety disorders, some patients also report significant problems with other emotions such as depression and anger. Techniques for dealing with depression can be found in

Chapter 6.3.2.3. Some empirically validated techniques for dealing with anger are described here. Although presented in the context of anger accompanying anxiety disorders, these techniques are also relevant to anger in other disorders and to people without an Axis I disorder.

(k) Cognitive content and other assessment issues

Anger is triggered when other people are seen to have broken one’s personal rules about what is right and fair.

(1) Angry individuals invariably think that they have been badly treated and ascribe their perceived ill treatment to intention or unacceptable neglect on the part of others. A key first step in assessment is to help patients become aware of their automatic thoughts during periods of anger. It is also helpful to keep a record of the situations and behaviours of other people that routinely trigger anger. Review of such triggers often reveals a particular theme and an implicit rule that the patient thinks other people should abide by. A detailed description of how the person behaves when angry and what effect the behaviour has on others is also essential.

(l) Intervention

As patients’ rules about the way that others should behave are often highly idiosyncratic, a useful tactic involves asking patients to consider whether the problem is assuming that others hold the same rule as them when they do not. This can help reduce the conviction that others’ actions are actively malicious. Other useful questions include the following.

Is there any other explanation for what happened?

Did the other people know that their actions would harm me?

Am I mind-reading?

Am I over-applying the ‘shoulds’?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of responding with anger?

Are there other ways I could behave which will be more likely to put things right/help me to get over it?

Although identifying and changing anger-related thoughts is a useful tactic, it is important to remember that anger is an actionorientated emotion. When angry, patients have a strong compulsion to hit out verbally or physically, and have great difficulty in thinking rationally. For patients with recurrent anger problems, it is often useful to teach them first to pause and relax or remove themselves from the anger-provoking situation before trying to challenge their thoughts and to delay-taking action (such as writing angry letters to others) until they have calmed down and had time to consider the appropriateness/usefulness of the action. To enhance further the generalizability of thought-challenging work, it is often useful to summarize the answers to typical angerrelated thoughts on a flash card that patients can carry around and consult whenever they become angry.

Anger can sometimes be the result of chronic under-assertiveness, with patients’ fears preventing them from making their point of view known until they feel overwhelmed and irritated by the demands placed on them. In such cases, discussion of the fears that prevent earlier and more appropriate assertion and role-playing in which the patients try out and evaluate ways of communicating their views to others in a prompt and constructive fashion can be helpful.