chapter 11

Common Neck, Arm and Upper Back Problems

Neck and arm pain and sensory disturbance with or without weakness in the arm are very common complaints. This chapter will discuss the more frequently encountered peripheral nervous system (lower motor neuron)1 problems and the non-neurological conditions seen in everyday clinical practice. It will emphasise those features that help differentiate one problem from another. The chapter will be divided into three sections reflecting the regions of complaints most often seen in clinical practice:

Essentially there are only four neurological symptoms that can develop in a limb:

When a patient presents complaining of problems in the arm, for example, the important thing to establish is whether the symptoms relate to a non-neurological or a neurological problem and whether, if the latter, it is a peripheral (‘lower motor neuron’) or central (‘upper motor neuron’) problem. Remember the peripheral nervous system in the upper limb consists of the anterior horn cell in the spinal cord, the motor and sensory nerve roots, brachial plexus, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junctions and muscle. A central nervous system problem is anything above the level of the anterior horn cell, i.e. in the spinal cord, brainstem, deep cerebral hemisphere or cortex (see Figure 1.1). The pattern of weakness and sensory disturbance together with the reflexes will help determine whether the problem is central or peripheral. Finally, it is important to establish whether the symptoms are intermittent or persistent as different conditions present with either paroxysmal or persistent symptoms. Pain in the arm is only occasionally related to the nervous system but, when it is, it almost invariably indicates a problem in the peripheral nervous system as central causes of pain are very rare.

Symptoms arising from peripheral nerve lesions can arise as a result of three mechanisms:

• direct trauma, in which case the neurological symptoms will be present from the moment of trauma

• compression of the nerve (referred to as entrapment syndromes), in which case the symptoms will be persistent and, as the compression worsens, the severity of the symptoms (in terms of intensity and the extent of involvement of the muscles or area of sensation supplied by the particular nerve or nerve root) will increase

• irritation, which is also seen with entrapment syndromes, where the symptoms are initially intermittent and often provoked by certain activities; with repeated and prolonged irritation damage may result in persistent weakness and/or sensory loss.

NECK PAIN

Acute spasm of the neck muscles

The most common form is torticollis, often referred to as a ‘wry neck’. It is a self-limiting condition, resolving within days. More severe and disabling but very rare forms of congenital and acquired spasmodic torticollis occur [1] but are beyond the scope of this book.

Non-specific neck pain

The aetiology of this entity is uncertain but it is often encountered in patients with psychological problems such as anxiety or depression [2].

Whiplash

• Within the hours to first day or up to a few days after whiplash injury the patient complains of neck pain and stiffness, with or without a decreased a range of motion of the neck. Tenderness on palpation of the neck muscles and even the spinal processes is common. The pain may radiate into the shoulders or down the spine to the thoracic region.

• Headache frequently occurs together with insomnia, complaints of poor memory and difficulty concentrating [3].

• A small percentage of patients will develop non-specific and diffuse arm pain with or without subjective weakness and/or sensory symptoms in the arm that are clearly beyond the distribution of a single nerve or nerve root and are not related to nerve root compression. The pain and neurological symptoms in the arm, unlike cervical nerve root compression, are often aggravated by movement of both the arm and the neck while nerve root compression may be aggravated by movement of the neck but not the arm.

• Imaging is usually normal although in older patients degenerative disease may be seen and is often incorrectly invoked as the cause of the symptoms.

• The duration of symptoms varies from a few weeks to months or even years (the late whiplash syndrome, a controversial entity [4]), although 90–95% of patients experience only pain that settles within weeks.

The aetiology of whiplash is unknown and, curiously, it is not seen at all in Lithuania where there is little awareness of the syndrome and no accident compensation scheme [5, 6].

Cervical radiculopathy

Cervical radiculopathy arising from the 3rd and 4th cervical nerve roots is very rare. Unilateral pain in the suboccipital region, extending to the back of the ear, and in the dorsal or lateral aspect of the neck occurs with radiculopathy of the 3rd cervical nerve root. C4 radiculopathy results in unilateral pain that may radiate to the posterior neck and trapezius region and to the anterior chest but does not typically radiate into the upper extremity [7]. Neither is associated with any discernible weakness although neurological symptoms may occur with sensory symptoms in the distribution of the C3 or C4 nerve root and, in the very rare occurrence when a radiculopathy is associated with spinal cord compression, an upper motor neuron pattern of weakness in all four or just the lower limbs with or without sensory symptoms and a possible sensory level may result. The term ‘sensory level’ refers to the level within the central nervous system that the spinothalamic dermatomal sensory loss extends up to on the trunk or in the limbs.

PROBLEMS AROUND THE SHOULDER AND UPPER ARM

Pain with or without focal neurological symptoms in the shoulder and upper arm

• nerve root compression of the 4th, 5th and 6th cervical nerve roots

• suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome

• arthritis of the shoulder joint

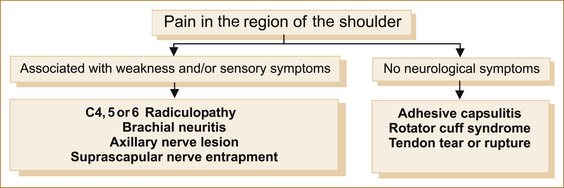

Figure 11.1 lists the common causes of pain in the region of the shoulder.

NEUROLOGICAL CAUSES

Radicular pain: Pain from nerve root compression, if associated with weakness and/or sensory disturbance in the distribution of the nerve root, is readily diagnosed. However, pain may occur in the absence of or precede neurological symptoms by days or even weeks. Although radicular pain may affect the upper (C4–C5) arm, it is more common in the lower (C6–8) arm.

Numbness and/or localised shoulder pain not influenced by movement of the shoulder suggests a possible C5 nerve root problem. Where neurological symptoms and signs develop, the numbness is located over the top of the shoulder along its mid-portion and extends laterally to the upper arm but not into the forearm. There may be weakness of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and deltoid muscles [7].

Brachial neuritis or neuralgic amyotrophy: The diagnosis should be suspected when severe shoulder pain aggravated by movement of the shoulder is associated with weakness and sensory disturbance in the arm. Van Alfen et al [10] have described the clinical details in a large series of patients. As there is no ‘gold standard’ diagnostic test for brachial neuritis, the clinical features of neuralgic amyotrophy are likely to evolve.

SYMPTOMS: The classic symptoms begin with the subacute onset over weeks of increasingly severe constant unilateral pain predominantly in the shoulder girdle; less commonly, the pain may come on rapidly. Rarely, bilateral cases occur but one side is usually affected for some hours or up to 2 days before the other side is involved [11]. This constant pain persists on average for approximately 3–4 weeks but may last as little as a few days or up to 60 days or more. In many patients it may be followed by a movement-evoked severe stabbing pain that can persist for months. In a small proportion of cases the pain can radiate from the shoulder to the arm, the cervical spine or neck down into the arm, the scapular or dorsal region to the chest wall and/or arm, or be confined to a lower plexus distribution (e.g. medial arm and/or hand, axilla).

The shoulder pain is aggravated by movement of the shoulder, not the neck, but here there are neurological symptoms such as weakness and sensory disturbance in the arm that indicate a neurological cause for the pain. Although local heat to the shoulder region occasionally provides some relief from the pain, this is non-specific and cannot be used in diagnosis. Individual nerves can be affected in brachial neuritis, in particular the suprascapular, axillary, musculocutaneous, long thoracic and radial nerves [11].

Progressive weakness developing over days may commence within 24 hours after the onset of the pain or may be delayed for up to 4 weeks [11]. Although any part of the plexus can be involved, the upper brachial plexus is more commonly affected in males whereas the middle and lower brachial plexus is more commonly affected in females. Wasting may occur with prolonged symptoms. Recovery can take months or even years. Sensory involvement is common and sensory symptoms can be very diffuse and non-localising.

Recurrence is rare but can occur and familial cases, termed hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy, have been described. Hereditary neuropathy with pressure palsy can also cause neuralgic amyotrophy and is related to a defect in the peripheral myelin protein 22 and is regarded as a distinct disorder [12].

Axillary nerve lesion: Axillary nerve lesions are usually related to traumatic dislocation of the shoulder joint as a result of either a sporting injury or secondary to a tonic–clonic seizure. Less commonly they occur with a fracture of the neck of the humerus or following shoulder surgery. As with all single nerve (mononeuritis) lesions, some are idiopathic (unknown cause).

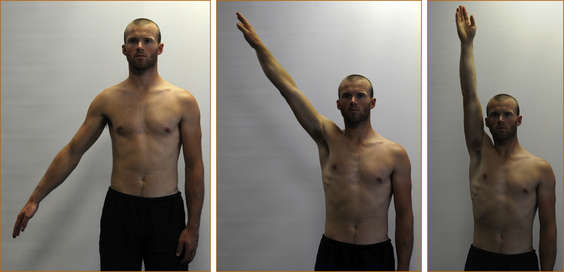

EXAMINATION: There is weakness of shoulder abduction beyond the first 30° (the initial 30° is supplied by the supraspinatus muscle) due to weakness of the deltoid muscle (see Figure 11.2). There may be a small patch of numbness over the lower aspect of the deltoid muscle. When the lesion relates to dislocation, there is often pain in the shoulder aggravated by movement of the shoulder. The presence of pain and weakness with a history of trauma to the shoulder is a strong pointer to the diagnosis. The prognosis for recovery is variable [13].

Suprascapular nerve entrapment: The suprascapular nerve arises from the junction of the 5th and 6th cervical nerve roots and traverses an oblique course across the supraspinatus fossa, relatively fixed on the floor of the fossa and tethered underneath the transverse scapular ligament, to the scapular notch and supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. Most often the suprascapular entrapment syndrome relates to local compression by the suprascapular ligament although it may be idiopathic in origin or due to rarer causes [14]. Although very rare, it is a diagnosis not to be missed as prompt treatment is more likely to result in resolution of the problem.

SYMPTOMS: The pain is deep and diffuse, localised to the posterior and lateral aspects of the shoulder and may be referred into the arm, neck or upper anterior chest wall. Certain scapular motions may be painful, causing the patient to restict shoulder movement. Adduction of the arm across the body tenses the nerve and may increase the pain. Occasionally, the patient may complain of burning, aching or crushing pain.

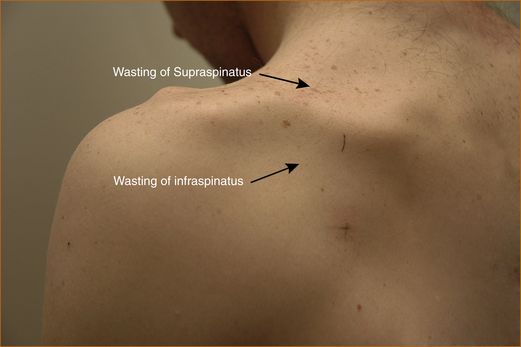

EXAMINATION: It is important to test the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, looking for weakness confined to those muscles. Remember, pain may give the appearance of weakness with the patient not exerting a full effort as a result of the pain. The clue that the weakness relates to pain from the shoulder is that, in addition to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus appearing weak, the deltoid and subscapularis muscles will also appear weak. Severe suprascapular nerve entrapment results in atrophy and permanent weakness of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles (see Figure 11.3).

FIGURE 11.3 Suprascapular entrapment with marked wasting of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles

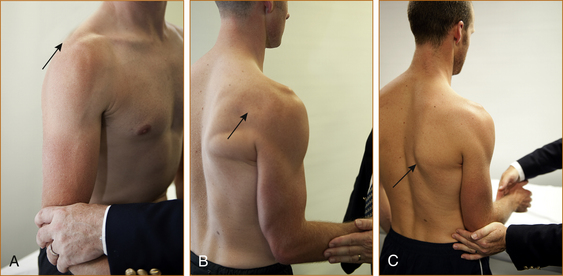

FIGURE 11.4 A Method of testing the supraspinatus. The arm is abducted approximately 20–30° away from the chest wall while the examiner pushes on the elbow, trying to force the arm back against the chest wall.

B Method of testing the infraspinatus. The elbow is kept next to the chest wall and the semi-flexed forearm is externally rotated against resistance.

C Method of testing the subscapularis. The arm is bent at a right angle at the elbow and the forearm is semi-pronated. The elbow is kept at the side and the patient is asked to rotate the forearm in towards the body while the examiner tries to prevent this by pushing the forearm in the opposite direction.

NON-NEUROLOGICAL CAUSES OF SHOULDER PAIN

Adhesive capsulitis: Adhesive capsulitis or the ‘frozen shoulder’ results in a gradual onset of pain and stiffness that leads to a restricted range of movement at the shoulder joint. It is usually seen in patients over the age of 40. A normal range of movement of the shoulder is incompatible with the diagnosis and X-rays are usually normal. The aetiology of this condition is unclear but it is not uncommon in the setting of a hemiplegia.

Rotator cuff syndrome: Probably the commonest cause of pain affecting the shoulder joint is non-neurological and is related to rotator cuff syndrome, also referred to as impingement syndrome. There are four tendons in the rotator cuff and these tendons are related individually to the following muscles: teres minor, subscapularis, infraspinatus and supraspinatus. The rotator cuff is compressed against the acromium causing bursitis, tendinitis and eventually a rotator cuff tear. Partial or complete tears or inflammation (tendinitis, tendinosis, calcific tendinitis) associated with rotator cuff injury occur in the region near where these tendon/muscle complexes attach to the humerus [17]. Other causes of pain in the shoulder joint include adhesive capsulitis and arthritis.

SYMPTOMS: Symptoms are generally those of pain, initially after and then during activity. The pain can often be relieved by rest. Patients over 40 years of age are more susceptible to rotator cuff tendinosis with overuse. In this age group the most prominent complaint is pain with overhead use and athletic activities. Night pain and an inability to lie on that side are also common [17]. Although the pain may radiate into the arm and the neck it is clearly related to movement of the shoulder and not the neck, indicating local shoulder pathology and not radicular pain. Pain in the shoulder between 60° and 180° of elevation is typical of a rotator cuff problem and is termed the painful arc syndrome (see Figure 11.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree