OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Describe how health professionals may promote health equity through community engagement.

Discuss the importance of partnering with the community.

Outline how a health professional can engage with a community, including the Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC) model.

Discuss how to define a target community.

Describe techniques of healthy community assessment.

Explain how health professionals can promote community empowerment.

Health depends, in large part, on the social context within which a person lives. Community, a concept derived from the Latin word communitas, meaning common or shared,1 will be defined in this chapter as a group of people with a shared identity. The community or communities with which an individual identifies define their social context and are potent determinants of health (see Chapter 1).

Engaging with communities to address the broader social and environmental conditions that undermine health is an important role for health professionals. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (http://www.cdc.gov/phppo/pce/) defines community engagement as “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people.”2 Community engagement is a powerful tool for the promotion of health and health equity.

By partnering with a community, learning about its needs and resources, and assisting a community with community-based health interventions, health professionals have the potential to improve the well-being of many more people than they care for individually in clinical settings. For example, health professionals participating in addressing issues like eliminating “food deserts” in low-income communities, or contributing to community-based efforts to prevent violence, can contribute greatly to these endeavors. Ultimately, these efforts improve the health of their patients. One approach is through advocacy work, publicizing and campaigning for policy and political changes to reduce inequities (see Chapter 8). Another approach is to directly engage with members of underserved communities and community-based organizations and partner with them to implement programs at the local level.

This chapter discusses concepts and strategies for health professionals seeking to engage with communities at home and abroad, focusing particularly on community partnership and community assessment. Woven through this chapter is the story of the establishment of the San Diego, California–based Environmental Health Coalition (www.environmentalhealth.org) and its community health worker (or promotora) program.

PARTNERING WITH COMMUNITIES

The Environmental Health Coalition (EHC), a grassroots community organization, was founded in San Diego in 1980. It initially worked with union members concerned about occupational health and safety issues and community members concerned about cancer and other environmental illnesses. Founders included industrial workers, environmentalists, health and human service providers, and university professors. Their mission statement includes: “We believe that justice is accomplished by empowered communities acting together to make social change.”3 Health professionals from several southern California universities, including the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), have been involved in many of the projects undertaken by EHC.

The notion of partnership is fundamental to community engagement. Community health interventions by health professionals, whether domestic or international, are much more likely to be effective if they are done in partnership with that community. A community-based project is likely to be more successful than a community-placed project. A community-placed project is one in which an outside “expert” assumes she or he knows what a community needs, develops an intervention without community input, and then implements it. This can lead to (a) a project that is not valued by the community because it is not addressing one of the community’s priorities; (b) methods that are culturally inappropriate; (c) duplication of interventions that have already been tried; and (d) a project that is not sustainable beyond the expert’s involvement because it does not have community support. A true community-based project is one that grows from within a community and is led by community members. Community members identify needs and resources, implement an intervention, and sustain the project. Outside experts can participate in this process through effective partnering.

Box 6-1 lists important tasks for health professionals embarking on community engagement. We discuss these tasks in more detail in the following sections.

Box 6-1. Important Tasks When Embarking on Community Engagement

Assess your own resources as a health professional and your short- and long-term interest in becoming partners with the community.

Engage the community by identifying the relevant social networks and leaders and beginning to build relationships.

Prioritize health problems using consensus-building techniques.

Develop strategies to enlist community involvement in the intervention.

Evaluate outcomes, involving the community from the start.

From Wallerstein N, Sheline B. Techniques for developing a community partnership. In: Rhyne R, Bogue R, Kukulka G, et al. (eds). Community-Oriented Primary Care: Health Care for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 1998.

COMMUNITY-ORIENTED PRIMARY CARE MODEL

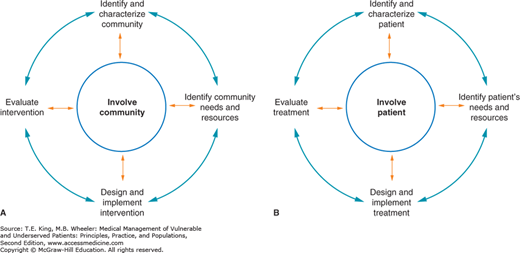

There are many models for community-engaged work. One well-established framework is Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC), a process through which health issues of a defined population are systematically identified and addressed.4 Figure 6-1A shows a diagram of the COPC process. The first step is identifying and characterizing a target community. The second step is assessing the needs and resources of that community. The third step is designing and implementing an intervention to address a prioritized need. The fourth step is evaluating the success of the intervention. Involving the community at all stages is an integral part of the COPC model. Community members must be involved as partners, not merely as a source of data. Examples of this partnership include community members who help to define the target community, pose research questions, design survey instruments, gather and/or analyze data, prioritize health issues, design and/or staff interventions, perform evaluations, and write up results. It is ideal if community members have already initiated a community development process along the lines of COPC, and they invite the health professional to join them.

Figure 6-1.

Comparison of community-oriented primary care (COPC) and patient care models. A. COPC process. (Adapted with permission from Rhyne R, et al. Community-Oriented Primary Care: Health Care for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 1998.) B. Patient care process.

The COPC model is not unlike the process health professionals go through in caring for individual patients. See Figure 6-1B for a diagram of the patient care process. Patient care cannot be successful unless the health professional collaborates with the patient at each step. Patients are not only expected to provide information about their health problems. They are also expected to participate in treatment decisions, changing health behaviors, and monitoring their progress. Similar to engagement at the community level, it is ideal at the individual level if patients are taking the initiative to improve their health and involve a health professional to assist them.

Closely related to COPC is the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model.5,6 True CBPR is research that embodies core principles of COPC, including community assessment and community engagement.

OVERCOMING THE CULTURAL DIVIDE AND DEVELOPING TRUST

Awareness of the cultural divide that often exists between health professionals and underserved communities, and approaching community partnerships with humility, are foundational competencies for successful community engagement. Like all human beings, health professionals have their own biases and cultural norms, and effective community engagement, like effective patient engagement, requires self-awareness. Many health professionals are not members of the communities they serve. This is especially likely to be true for health professionals serving vulnerable populations at home or abroad. Not being a member of the community often means that health professionals face a cultural divide. This divide may include race, ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, or belief systems, to name a few possible differences. These differences are magnified when working in a foreign country. Just as health professionals strive for cultural competence when delivering health care to individuals, they must work on learning about the realities of community life if they want to engage successfully with a community. Tervalon and Murray-Garcia suggested the term “cultural humility” rather than cultural competence.7 They described cultural humility as incorporating “a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient–physician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities.”

The cultural divide commonly includes the gap between the academic medical perspective and the community perspective.8 Freeman describes the academic perspective as more focused on theory, analysis, and educational value, and the community perspective as more focused on practical solutions, service, and action. Because of their different perspectives, academics sometimes behave in ways that are or appear to be disrespectful and generate mistrust in the community. For example, academics performing research in a community may promise to share results with that community; however, the communication of results may never happen. This missed step can represent a betrayal of trust from the community’s perspective. Explaining what to expect of an academic approach and integrating elements of a community perspective may improve academic–community partnerships.

Trust tends to develop over time with long-term relationships, but health professionals often come into a community for a relatively short period defined by the duration of a course or a grant-funded project. Repeated experiences like this can leave community members feeling used and mistrustful of other health professionals who try to engage with them. Needs assessments that identify pressing social issues but do not lead directly to a subsequent intervention can be frustrating for community members.

Another potential element of the cultural divide between health professional and community is the paternalistic role that health professionals have often played with their patients—a role that may be extended into community work, with poor results. When doing international work, this can be reminiscent of the damaging effects of colonialism. When health professionals assume that they know what would be best for the health of their target community, they may alienate and disempower community members. Conversely, taking a more collaborative approach and heeding the collective wisdom within the community is more likely to build trust and promote community empowerment. Community members know their communities best and usually have considerable wisdom and practical perspectives about solutions to community problems. Both locally and globally, health professionals engaging with community members can ask for them and their communities to recommend solutions. Health professionals should listen when solutions are offered, sincerely consider these possible solutions, and respectfully offer or add their own expertise as health professionals to help the project succeed. This can lead to increased trust as well as increased likelihood of success, as the combination of community expertise and professional expertise often yields the best intervention strategies.

ENGAGING THE COMMUNITY

Barrio Logan is a San Diego neighborhood with a mix of residences and industry, nestled between Interstate 5 and San Diego Bay’s shipyards, 20 miles from the border with Mexico. Most of the residents of San Diego’s Barrio Logan neighborhood are Latino, and 33% of families are living in poverty. There are strong community associations, ranging from labor unions to informal social networks of women.

Engaging the community involves two initial steps: defining the community, and gaining entry into the community and developing partnership.

There are several ways to define a targeted community: (a) a geographically defined neighborhood; (b) a group of people working or going to school together; (c) a group of people with some shared sociologic characteristic such as age, language, and a shared history, cause, or identity; or (d) a clinically defined population, such as persons with a particular health problem or patients served by a particular clinic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree