Other studies have demonstrated similarly high levels of traumatic exposure in the general population (Breslau, Davis, Andreski, & Peterson, 1991; Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993). However, not all shocking experiences—and perhaps not even most traumatic events—result in PTSD. The NCS determined a lifetime prevalence of PTSD at 7.8% (Kessler et al., 1995), much higher than previous estimates of around 1% (Davidson, Hughes, Blazer, & George, 1991; Helzer, Robins, & McEvoy, 1987), probably because of differences in diagnostic criteria and assessment procedures. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2005), conducted between 2001 and 2003, sampled 5,692 participants, using DSM-IV criteria. The NCS-R estimated the lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans to be 6.8%, a very similar figure to the first NCS.

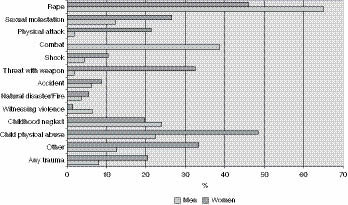

The nature and severity of the traumatic events may influence whether prolonged psychological effects will occur. There were significant gender differences concerning the likelihood of developing PTSD for many different types of trauma (Figure 2.2). In the NCS, the types of trauma in men that were more likely to lead to PTSD included rape, combat exposure, childhood neglect, or childhood physical abuse; women were more likely to become symptomatic following sexual molestation, physical attack, being threatened with a weapon, or childhood physical abuse (Kessler et al., 1995).

The probabilities for developing PTSD were generally higher for life-threatening events than for those that were of lower impact. Of particular note was the finding that although men were more likely than women to be exposed to traumatic conditions, women were twice as likely as men to develop PTSD. This result might point to women’s increased vulnerability to develop PTSD, or more likely to the more severe sequelae of certain forms of traumatization, because women were overwhelmingly more likely than men to be the victims of rape or sexual molestation (odds ratio of 13 to 1).

Posttraumatic responses to brief or single overwhelming events in an otherwise intact person tend to be less severe and shorter-lasting. Many such experiences spontaneously resolve or become muted with time and encapsulated deep in the psyche, reappearing only in nightmares and under conditions of severe stress. However, the NCS found that more than one-third of people with an episode of PTSD failed to recover even after many years (Kessler et al., 1995). Persistent and disabling trauma-related responses are usually associated with those who have been exposed to particularly severe or chronic traumatization. The most severe forms of PTSD seem to result from certain types of prolonged childhood abuse, chronic combat experiences, or long-term domestic violence.

There are individual variations in response to stressful events. Some persons have more capacity to cope with trauma and greater resiliency to tolerate and recover from such experiences. Besides the type and severity of the traumatic experience, the reported risk factors for developing PTSD are preexisting psychiatric disorders, adverse childhood experiences, lack of social support, low socioeconomic status, lower intelligence, and family history of mental illness and/or substance abuse (Brewin et al., 2000; Davidson & Fairbank, 1993; Green, 1994; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). Trauma research has not yet sufficiently explored populations that have been exposed to trauma and do not develop posttraumatic difficulties. An emerging area of study in psychology has looked at resilience to loss and trauma and has begun to identify the characteristics of individuals who seem to fare better under adverse circumstances (Bonanno, 2004). A personality trait that has been called “hardiness”—which includes the beliefs that life is meaningful, that one can have control over the outcome of events, and that one can learn and grow from life experiences (Kobasa, Maddi, & Kahn, 1982)—has been linked to resiliency to trauma. However, many patients with severe and disabling posttraumatic responses have histories of extreme trauma such as malignant childhood abuse. Such experiences interfere with the development of healthy resilience, such as the characteristics of hardiness, and it is difficult to imagine that experiences of this sort would be well tolerated by any individual regardless of coping capacity.

The DSM-IV has the following criteria for PTSD (APA, 1994, pp. 427–428):

Criterion A: Stressor

The person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which both of the following have been present:

1. The person has experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others.

2. The person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Note: In children, it may be expressed instead by disorganized or agitated behavior.

Criterion B: Intrusive Symptoms

The traumatic event is persistently reexperienced in at least one of the following ways:

1. Recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections of the event, including images, thoughts, or perceptions. Note: In young children, repetitive play may occur in which themes or aspects of the trauma are expressed.

2. Recurrent distressing dreams of the event. Note: In children, there may be frightening dreams without recognizable content.

3. Acting or feeling as if the traumatic event were recurring (includes a sense of reliving the experience, illusions, hallucinations, and dissociative flashback episodes, including those that occur upon awakening or when intoxicated). Note: In children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur.

4. Intense psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

5. Physiologic reactivity upon exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

Criterion C: Avoidant/Numbing Symptoms

Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by at least three of the following:

1. Efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversations associated with the trauma

2. Efforts to avoid activities, places, or people that arouse recollections of the trauma

3. Inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma

4. Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities

5. Feeling of detachment or estrangement from others

6. Restricted range of affect (e.g., unable to have loving feelings)

7. Sense of foreshortened future (e.g., does not expect to have a career, marriage, children, or a normal life span)

Criterion D: Autonomic Hyperarousal

Persistent symptoms of increasing arousal (not present before the trauma), indicated by at least two of the following:

1. Difficulty falling or staying asleep

2. Irritability or outbursts of anger

3. Difficulty concentrating

4. Hypervigilance

5. Exaggerated startle response

In addition, the DSM-IV requires that the PTSD symptoms be present for more than one month (similar symptoms for less than a month are diagnosed as acute stress disorder). PTSD is considered to be chronic if the symptoms are present for more than three months. The DSM-IV describes the occurrence of delayed onset, in which symptoms emerge more than six months after the event. One variant of delayed onset occurs in conjunction with complete or partial amnesia for traumatic events. When the memory is recovered—often years later—acute PTSD symptoms erupt, often with vivid, detailed intrusive memories and flashbacks along with severe autonomic hyperarousal, as though a defensive barrier has been breached. In retrospect, some of these persons with delayed recall realize that they had been in a somewhat chronic, numbed state before the return of the memories.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

From a treatment perspective, it is important to correctly diagnose patients’ difficulties and to understand the etiology of their symptoms. For example, although many traumatized persons meet the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive disorder, it is more helpful to recognize the symptoms as being trauma related: depressed and anxious mood (related to PTSD and borderline personality), emotional constriction and numbing (related to PTSD and dissociation), social withdrawal (related to PTSD and borderline personality), hopelessness and a sense of foreshortened future (related to PTSD), helplessness (related to PTSD and borderline personality), and self-destructive thoughts and behaviors (related to PTSD and borderline personality). If the symptomatology is truly trauma-related, patients will not optimally respond to treatments for major depression such as antidepressant medication. In our study comparing patients with childhood trauma to nontraumatized patients with major depression (Chu, Dill, & Murphy, 2000), both groups met DSM-III criteria for major depressive disorder and had many classic neurovegetative signs and symptoms of depression, including loss of energy, interest, and motivation, sleep and appetite disturbance, guilt, and suicidal thoughts. The only symptoms that seemed to differentiate the two groups had to do with the characteristics of the sleep disturbance. The depressed group endorsed difficulties in falling asleep despite feeling tired, and midsleep awakening with the inability to fall back to sleep. The patients with trauma had difficulty falling asleep because they were too anxious or fearful to sleep, and they subsequently woke up multiple times during the night with anxiety that was sometimes caused by traumatic nightmares.

Given the distressingly high prevalence of trauma, it is not unusual for some patients to have true comorbidity in addition to trauma-related syndromes. That is, traumatized patients may have major mood and anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses, dementia, delirium, or organic states. In these situations, it is usually imperative to treat the non-trauma-related difficulties as the first priority. Serious psychiatric illness is a major internal stress on the body and mind, and because posttraumatic and dissociative symptoms are stress-responsive, these trauma-related symptoms may be heightened by untreated comorbid disorders, as in the following example:

Esther, a 63-year-old, single woman was admitted to a psychiatric hospital with florid PTSD symptoms. She had intrusive thoughts almost continuously about known physical and sexual abuse that had occurred after she was abandoned as a child and raised in a series of foster homes and institutions. She was particularly fearful at night, having flashbacks and seeing images of menacing men outside her window. A closer examination of her symptoms suggested that Esther was suffering from major depression with psychotic features. She showed extreme psychomotor retardation, barely moving from her bed or chair, had sustained a recent 20-pound weight loss, and spoke of feeling that her “insides” were decaying. A brief course of electroconvulsive treatment followed by medication brought about a remarkable change. She recompensated with improvement in both her mood and PTSD symptoms. Although she still thought about her early abuse, the thoughts did not overly disturb her, and she was able to return to her previous level of functioning.

It is also not unusual for certain psychotic disorders to mimic trauma-related syndromes, as in this clinical illustration:

A 24-year-old man was referred for evaluation for PTSD. He had recently had several episodes where he had the abrupt onset of episodes of intense anger, agitation, and anxiety, which he attributed to possible sexual abuse by an older family member such as his father, uncle, cousin, or older brothers. When asked if he had memories of the abuse, he admitted that he had no such recollections and had never previously suspected abuse, but he felt that this was the only explanation for these episodes. He was preoccupied with fantasies of avenging himself for having been molested, but he was unclear which family members might have abused him.

It became clear that he also had vague but intense worries about other issues, such as the idea that he might have been sexually abused by a priest in his church (without any memory or indication of such) and that he might be homosexual (despite all evidence pointing to heterosexual orientation). He reported a sense of emptiness and a sense of detachment from others (including parents who he described as caring and supportive) and difficulties functioning; these problems had been increasing since his midteen years. In addition to his apparent paranoia, he admitted that his thinking was often extremely scattered, disorganized, and confused. In consultation with his treating psychiatrist, it was clear that the diagnosis of PTSD was unlikely and that schizophrenia or another psychotic illness was more probable.

COMPLEX PTSD

In several ways, it is not entirely helpful to accept the criteria for PTSD as defined in the DSM-IV as fully describing the aftereffects of trauma. First, PTSD rarely exists in isolation. More often, particularly in cases that become chronic (i.e., symptoms persist for more than three months), extensive comorbid conditions complicate treatment and recovery. Second, the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria are very limited and do not include some important changes that occur universally in PTSD, such as fundamental shifts in the way that trauma survivors see themselves and the world. In order for the concept of PTSD to be most useful, one must consider how it customarily presents in real-world situations and how to optimally understand and treat the multiple difficulties that PTSD sufferers experience. It is also important to understand the limitations of treatment outcome research. In order to have clean participant samples that will eliminate unnecessary variables, researchers generally exclude those patients with extensive comorbidities. Hence, some research findings concerning efficacy of treatment have only limited applicability and may not be relevant to many PTSD patients seen in clinical practice.

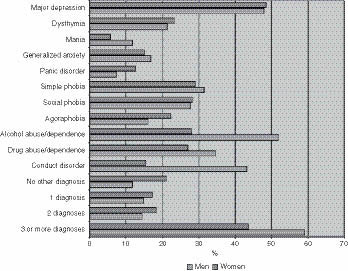

It is striking to note how commonly PTSD patients have multiple comorbidities (Figure 2.3). In the NCS, the vast majority of participants who had PTSD at any point in their lifetime qualified for at least one other diagnosis during their lifetime; approximately half qualified for more than three diagnoses (Kessler et al., 1995).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree