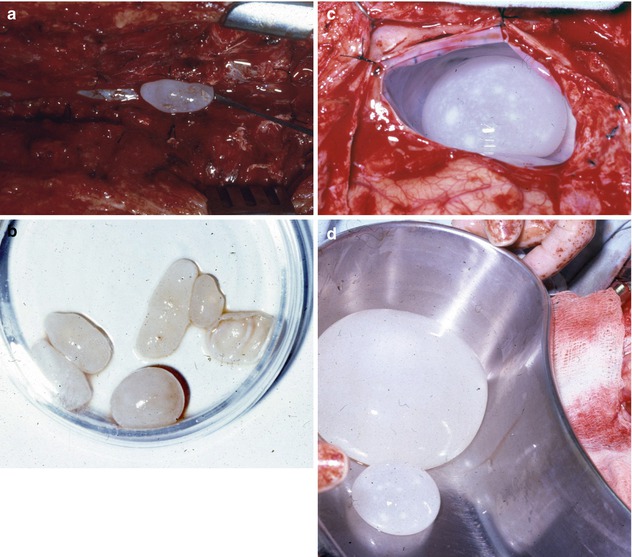

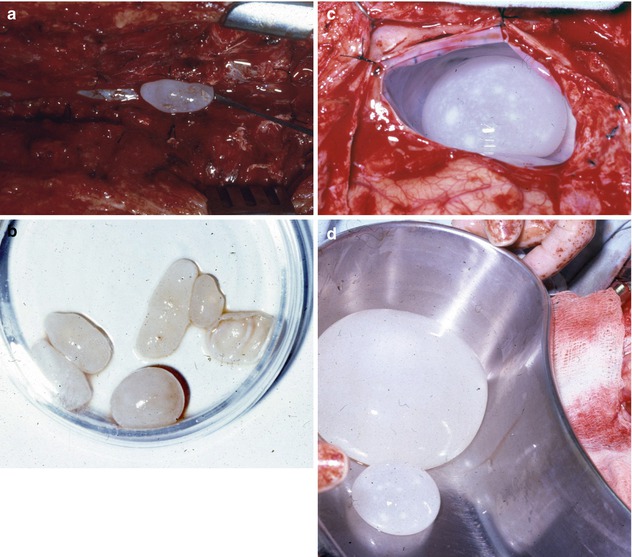

Fig. 17.1

(a) Delivering the cyst by applying the Credé maneuver. (b) Opened cyst showing the multitude of daughter cysts. (c) The cavity left by the cyst, note the uncollapsed cyst bed because of the calcification

Infected or Complicated Cysts

Although most authors use the term “infected,” some use the term “infected or complicated” cyst (El-Shamam et al. 2001). The term complicated is more appropriate as, in spite of an extensive search in the literature, nothing has been found concerning the pathogenesis nor the pathogens in these cases. The cultures of the pus in the cases of Ersahin et al. (1993) and Turgut et al. (1997) did not yield any growth. In these cases, rim enhancement and paracystic edema are seen on computed tomography (CT) scan (Krawjewski and Stelmasiak 1991). The best method of diagnosis is by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which reveals “varying degrees of perifocal edema and contrast enhancement” (El-Shamam et al. 2001), and Nourbakh et al. (2010) report on T2 imaging a “hyperintense area of perifocal edema, complete and incomplete (segment) rim of contrast enhancement.” These cysts become so adherent to the surrounding brain that their delivery intact becomes next to impossible (Rudwan and Khaffaji 1988). Mathuriya et al. (1985) described a case of infected intradural extramedullary hydatid cyst at the foramen magnum.

In 1948 Obrador and Urquiza reported a 9-year-old girl who harbored a “large” infected cyst in the left frontoparietal region. This was excised, and the culture of the pus did not yield any growth. This case is interesting because the abscess had formed around a shrunken hydatid vesicle measuring 7 cm in length. It is not clear whether the abscess was primarily pericystic or intracystic, and, with the rupture of the cyst in situ (see section “Spontaneous intracerebral rupture of the cyst”), the pus poured to the outside. Zahed et al. (2010) reported a case of infected hydatid cyst occurring prior to surgical intervention in a 20-year-old female suffering from a tender cystic swelling over the right temporal region associated with proptosis of the eye on the same side. The histopathology of the excised specimen was reported as an infected hydatid. The frequency of these infected cysts is extremely low, yet El-Shamam et al. (2001) found 4 out of 16 cases, and Kocaman et al. (1999) reported it in 3 out of 23 cases. An interesting case is that of Erongun et al. (1994) where an infected cyst was removed from the left occipital lobe of a 12-year-old boy with multiple adjacent cysts which were not infected. Twenty days after surgery, a cyst was found on CT scan in the left temporoparietal region. The family refused surgery. Fifty days later the child went into deep coma and died in spite of a rapid decompression by needle aspiration. The author does not mention the consistency of the fluid obtained.

Could it be possible that the cyst, which was found in the left temporoparietal region, had been missed at the time of surgery and, relieved from the surrounding pressure, rapidly expanded, in a matter of 70 days? This lapse of time is too short for a new cyst to produce symptoms.

Another interesting case is that of Goinard and Descuns (1952) where a thin blade of sterile pus was localized in the space between the ectocyst and a markedly thickened pericyst.

Other single cases have been reported in the literature (Obrador and Urquiza 1948; Arana-Iniguez and San Julian 1955; Boixados 1973; Mathuriya et al. 1985; Turgut et al. 1997; Turgut and Turgut 2002; Polat et al. 2003).

Although the content of these complicated cysts were considered as sterile, from the point of view of hydatid recurrence, the case of Yuceer et al. (1998), proved the opposite. They reported on a case 12-year-old child. A year earlier, the patient harbored “a large hydatid cyst with rim enhancement and calcification of the cyst wall.” At operation the cyst ruptured and “purulent material” was drained. The patient presented a year later with multiple recurrent cysts in the bed of the previously removed infected and calcified cyst. This is why these cysts have to be as carefully delivered as are regular hydatid cysts.

Caseation

Caseation of the cyst content was described by Kooy (1940) in two cases. Both cases had peripheral calcifications. In one of these cases, the caseous material contained hooklets, and in the second there was a conglomeration of daughter cysts. It is not known whether these hydatid particles were active or dead. Radwan and Khaffaji (1988) reports on a patient whose cyst was filled with “mucoid gelatinous material,” and there were adhesions between the dura, arachnoid, and overlying cortex. This case too showed, on plain skull films, a “fairly round, calcified lesion. When the cyst capsule was incised, mucoid gelatinous material was evacuated.” No other reference related to caseation was found in the literature.

Chitinoma

Nanassis et al. (1999) resected from the frontal lobe of a 35-year-old woman a solid, partially cystic tumor, with focal calcifications, which on pathologic examination revealed an “acellular eosinophilic material with focal necrosis that surrounded typical protoscolices of Echinococcus granulosus.” This acellular material was identified as chitin, hence the nomination of this mass “chitinoma.” This term has been refuted by Turgut and Turgut (2002). It is interesting to note that there is a great deal of resemblance between this present case and those reported under “caseation,” which leads one to believe that this might be a more advanced case of caseation.

Hydrocephalus

Although hydrocephalus is not expected to be associated with such large cerebral supratentorial cysts, it does occur. El-Shamam et al. (2001) detected, on MRI, 4 preoperative hydrocephalics out of 16 patients and in only one was the cyst in the posterior fossa. Abbassioun et al. (1978) described two cases of hydrocephalus out of two posterior fossa cysts discovered on CT scan. Villarejo et al. (1983) reported such a case that required a ventriculoperitoneal shunt preoperatively later removed together with the cyst.

Leakage

Leakage of hydatid fluid in the surrounding tissues was reported to occur through a “thick porous” cyst wall (Griponissiotis 1957). This leakage produces a chronic type of inflammation with adhesions of the cyst wall to the surrounding tissues and its invasion with leucocytes. On CT scan and MRI, edema is observed in the surrounding brain. The description of the case of Gonzalez-Ruiz et al. (1990) is reminiscent of such a condition, although the authors believed it was an intracerebral rupture of the cyst. There was a hyperdense cyst wall visible on CT scan; the cyst was tightly adherent to the dura “producing inflammation and subsequent gliosis of the surrounding brain.” Could this leakage be the precipitating factor for the calcification in the pericyst? Nothing is found in the literature to refute or confirm this presumption. This condition makes the “delivery” of the cyst much more hazardous.

Spontaneous Intracerebral Rupture of the Cyst

This is an exceptionally rare condition and is accompanied by severe pericystic edema (Ozek 1994). It is usually ushered by an abrupt and important deterioration in the clinical status of the patient and may lead to dissemination of the disease. No reason for the spontaneous rupture of such cysts has been advanced except for that given by Griponissiotis (1957). He suggested that head injury may cause a cyst, adherent to the parietal dura, to rupture in the extradural space giving rise to numerous extradural cysts. He gave such an example. One of the causes of multiplicity of hydatid cysts in the brain may be due to the advent of a single cyst rupturing spontaneously in situ, as suggested by Nurchi et al. (1992). These authors removed approximately 30 cysts, measuring between few millimeters and 8 cm, from a single location (the right occipital lobe).

Bulging and Thinning of the Skull

The continued pressure and constant pulsations of those cysts lying adjacent to the peripheral dura, against the skull, produce, with time, bulging of the skull which may be extreme (Samiy and Zadey 1965). The skull in this area may become excessively thin. This thinning of the skull, described as early as 1888 by Vergo in the right frontal region in a 10-year-old child (quoted by Simpson and Verco 1976), may render the bone paper thin, a finding called “the parchment skull sign.” Dew described this aspect of hydatid disease as early as 1934. Phillips (1948) describes a case where “the bone was so thin that the flap could be cut with a strong scissors” (see Case 8).

Cysts Perforating the Skull and/or Dura

Phillips (1948) states that the “cyst had eroded the calvarium and was presenting beneath the scalp.” The skull is more at risk than the dura because the latter is more elastic. Should the pressure persist, the already thinned and necrotic skull disintegrates. This perforation was very well shown on a lateral MRI view in the article of Polat et al. (2003), where the brain, containing a cyst, passed through the skull to rest under the galea. Tizniti et al. (2000) describe a similar case. Goinard and Descuns (1952) made note of a case where the cyst had perforated the dura. It has also been described in intracranial extradural cysts (Samiy and Zadey 1965; Sharma et al. 2010; Zahed et al. 2010). Griponissiotis (1957) believed the pathogenesis of such a condition is due to an injury to the skull in the presence of an intracranial hydatid cyst attached to the dura. The latter ruptures and the cyst is forced outside the dura.

Stroke and Embolism of Cerebral Arteries

Stroke as a complication of cardiac hydatidosis is described in Chap. 22. Suffice it to say that this type of embolism is seen with ruptured cysts within the left cardiac chambers or wall as well as post excision of such cysts (Vaquero et al. 1982). It may produce multiple secondary brain cysts (Turgut et al. 1997; Ugur et al. 1998; Ait Ben Ali et al. 1999), a stroke (Martín Oterino et al. 1996; Yaliniz et al. 2004; Acarturk et al. 2004) which might be fatal (Byard and Bourne 1991; Ulgen et al. 2000), or both (Abbassioun et al. 1978; El Khamlichi 1993; Benomar et al. 1994; el Quessar et al. 1996; Kocaman et al. 1999).

Infertility

Tiberin et al. (1984) report a case of galactorrhea, amenorrhea, secondary sterility, and gain of weight of 2-year duration in a 29-year-old woman in whom no endocrinologic or gynecologic cause could be found and who recovered with restoration of fertility following the removal of an intact left frontal lobe cyst. Mazor et al. (1986) report on a similar case of a patient aged 31 who got pregnant less than 2 months following the excision of a left frontal lobe hydatid cyst, after 13 years of sterility. Both believe that this condition could be due to pressure exerted by the cyst on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

It would be interesting to include under this section the case of an 18-year-old male reported by Ozgen et al. (1984) who had an intrasellar cyst operated through a transsphenoidal approach. The hormonal profile which was on the low side preoperatively returned to normal within 10 months.

Nephrotic Syndrome

Sharma et al. (2010) report on a patient suffering from an extradural intracranial hydatid cyst associated with a nephrotic syndrome. This condition did not respond to the usual medical treatment but subsided when the cyst was removed. They believe that there must be cause-to-effect relationship between these two conditions. This syndrome was also reported, in the same article, secondary to pulmonary and hepatic hydatidosis.

Complications During the Treatment Period

There are two types of treatment: surgical and medical. These may be used simultaneously or separately, and each has its own set of complications.

Complications Related to the Surgical Act

These complications are many. In a review of 25 cases, Tuzun et al. (2010) reported 20 complications related to the surgical act.

Inadvertent Cyst Punctures During Ventriculography

Puncture of the cyst during ventriculography used to be one of the major complications when that test was about the only one available for diagnosis and localization of brain masses. This brought Brailsford (1931) to condemn its use when hydatid was suspected. When the cyst is punctured, the risk of spillage of hydatid fluid in the brain is very substantial, and recurrences may ensue. Philips (1948) warned against this complication and so did Griponissiotis (1957). Accidental cystography used not to be infrequent (Dew 1934). Fortunately, with the advent of the newer imagery techniques, including CT and MRI, this complication is only of historical importance. This complication is well represented in the following case.

Case 2

NT, a 10-year-old girl, was seen in June 1957 suffering from headache of 7-month duration accompanied by progressive right-sided weakness of 6.5-month duration. On examination, she had tremors in the right hand and crackpot resonance. Plain skull x-ray revealed separation of sutures. Ventriculography was carried out, and the cyst was inadvertently punctured. The films revealed a cyst in the left parietal region (Fig. 17.2). A small craniotomy was performed, and, through the intact dura, the cyst was twice filled with 1 % formalin which was left in the cyst cavity for 5 min each time and then irrigated profusely with normal saline solutions. The dura was then opened and the cyst removed through a small cortical incision. A severe postoperative reaction occurred, accompanied by fever, subsiding on the 13th postoperative day. A month after surgery, the patient was well. No further follow-up was possible.

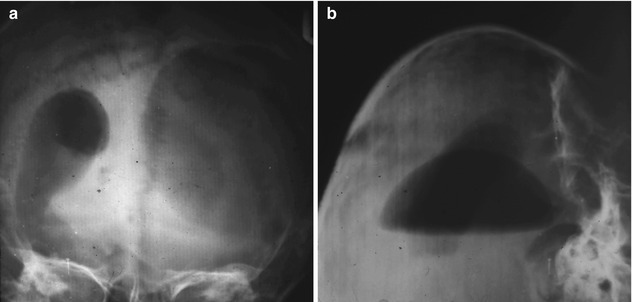

Fig. 17.2

(a) Ventriculography showing the injected cyst in AP projection. (b) Brow up lateral projection

Intentional Cyst Puncture

Cyst puncture is only indicated in extremis. It should never be carried out to decompress the brain before or at surgery. This is a most dangerous procedure as shown in the following case.

Case 3

RM, an 11-year-old boy, was seen for the first time on January 19, 1980, for headache of 3-year duration diagnosed as migraine. A month prior to his consultation, the headache became very severe, and a plain skull x-ray revealed separation of the sutures, with a decreased uptake in the left frontal area on isotope scanning. On examination there was no papilledema, but a crackpot resonance was obtained. Because of the above and his relatively good general condition, he was suspected of harboring a cerebral hydatid cyst. His family preferred him to be operated in France. His brother, a medical student who was accompanying him, was told that this was most probably a hydatid cyst and was asked to warn his surgeon in Paris not to puncture the lesion and that he, the surgeon, should be aware of that diagnosis and should do his best to deliver the cyst intact. The surgeon did not heed the advice and thought he was dealing with a cystic astrocytoma. When the dura was opened, the brain bulged, and the surgeon introduced a needle in the brain to reduce the pressure. Clear fluid spurted out and the brain relaxed; the surgeon carried out an incision in the cortex and pulled the chitinous membrane, closed the wound, and discharged the child in perfect health. This child was well until 8 months later, August 1980, when he suffered from headaches. CT scan of the brain became available in Lebanon; it was performed and revealed a cyst in the operative field. He was advised surgery but was lost to follow-up until March 28, 1981, at which time he suffered from severe weakness in the upper extremities with bilateral Babinski sign, absent knee and ankle jerks, saddle anesthesia, and urinary retention. He was being treated for a Guillain-Barré syndrome. A cisternal myelogram (CT myelography was not yet in use) revealed a complete block at C6. Following that test, the patient became completely paralyzed from C6 down with a flicker of movement in the left lower extremity. An emergency lumbar myelogram was performed with a puncture at L5–S1 to delineate the lower extent of the lesion. It revealed multiple subarachnoid space-occupying lesions extending from S2 to L2. The contrast medium did not flow beyond L2. The findings were suggestive of multiple subdural spinal hydatid cysts. An emergency surgery was performed on March 31, 1981, first on the cervical spine, from where a 3 cm cyst was removed intact from the spinal subarachnoid space at the C6 level. Then a laminectomy from S2 to L2 was performed, and four cysts were removed, two intact and two ruptured; the latter two had been punctured at the time of myelography (the needle punctures were clearly seen). The cervical and lumbar areas were thoroughly irrigated with 0.1 % cetrimide solution and the wounds closed. The patient gradually recovered his movements and sensations in the upper and lower extremities. Two weeks later, a myelogram, using the residual dye left in the spinal canal, revealed the presence of more cysts in the dorsal region (Fig. 17.3a). On April 16, a third laminectomy, joining the previous cervical and lumbar laminectomies, was performed, and the remaining six subarachnoid cysts were delivered intact from the dorsal region (Fig. 17.3b). The patient made a perfect recovery except for some urgency on urination and was discharged on May 1, 1981. On November 30, 1981, about 7 months after his discharge from hospital, he was readmitted because of bouts of headache and vomiting of 3-week duration. About 23 months from the initial surgery, on December 1, 1981, the left frontal craniotomy was reopened, and two recurrent frontal cysts were removed intact from the bed of the original cyst (Fig. 17.3c, d). Since then he has done well.

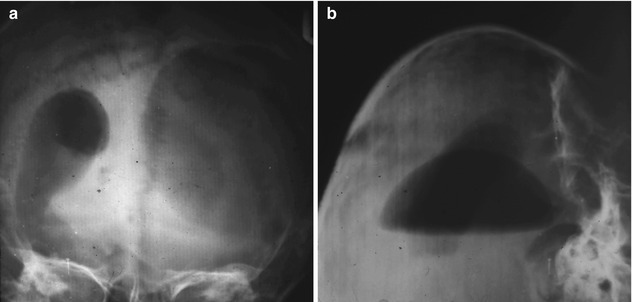

Fig. 17.3

(a) Delivery of cyst from the subdural space. (b) Cysts lying in a petri dish delivered from the dorsal space. (c) Cyst in situ in the cavity left by the previous surgery (note the thickened glistening pericyst). (d) Two recurring delivered cerebral cysts in a basin and the cavity left behind

Cyst Rupture

The most important and most catastrophic complication in surgery of brain hydatid is the inadvertent or intentional rupture of the cyst in situ at the time of surgery. It is generally estimated that 25 % of all operated cases rupture. Do these cysts have a topographic predilection for rupture during surgery? Deep-seated cysts tend to rupture more often than superficial ones, and cysts around the brain stem are more difficult to deliver intact. Onal et al. (2001) found that cysts in the frontal location were more prone to rupture and seven out of his eight cases, in this location, did rupture.

Most of these cysts are fertile, and, upon rupturing, the brain is flooded with hydatid fluid, disseminating the hydatid sand over a large area. However, only few cysts develop, rarely exceeding a dozen in number. The question which has not yet been answered is why, while such a large number of scolices (it is estimated that one cubic centimeter of hydatid fluid contains 400,000 scolices) soak the brain, only a few, if any, hatch and only a relatively small number of cysts develop (Case 3). Is it due to the host or to the parasite? Is it that when a scolex hatches, it produces some kind of an enzyme that inhibits the hatching of other scolices? Or is it that the brain develops a certain immunity against the parasite? In some cases, the seeding may reach the spinal subdural space. Case 3 is such an example.

What is the percentage of recurrences following cyst rupture? Griponissiotis (1957) reports on four cysts ruptures out of a total of eight cases, and out of the four there was only one recurrence. He attributes this low incidence of recurrence in ruptured cysts to the fact that he did sterilize the cyst by injecting in it formalin and by washing the cavity left by the cyst with formalin.

It takes an average of 6 months for these recurrent cysts to become fertile and 1 year to produce symptoms. Therefore, the golden rule is: in case a cyst ruptures intraoperatively, it is imperative to investigate the patient within 6 months, even though the patient may be asymptomatic. A negative investigation does not entirely exclude the possibility of a recurrence at a later date. This is why, if the investigations at 6 months are negative, the search should be repeated every 4–6 months for 4 years, as a 4-year period was found to be the maximum time for a recurrence to occur. In case recurrent cysts are found, it is indicated to operate on them before they become fertile, i.e., before 6 months elapse especially that these recurrent cysts usually lie deeper in the brain and their delivery, intact, becomes more difficult. They may at times be found within the lateral ventricle (Case 4) or even in the spinal subarachnoid space (Case 3). In case the cyst recurs in the same place occupied by the original one, often the pericyst is much thicker than usual and is adherent to the adjoining brain and may mimic the appearance of the ectocyst. There may also be fluid between the thickened pericyst and the ectocyst as in our Case 3 (Fig. 17.3c).

To prevent such complications, in case of rupture, it is advisable to adapt surgery in a way to reduced damages to a minimum. As Benjamin Franklin once said “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” What kind of prevention should be applied? If one adopts the following five rules, one is prone not only to prevent rupture but, in case of rupture, to minimize the damage:

Rule one: Do not allow any sharp instrument or material to be found in or near the surgical field. Cover with wet gauze all Raney clips, and cover all sharp objects in the vicinity of the cyst, like clamps, hooks, bony edges, etc., with a wet gauze.

Rule two: Do not use the cautery (uni- or bipolar) in the vicinity of the cyst. Open the cortex or enlarge the opening using a pair of scissors and applying clips whenever indicated. After the delivery of the cyst is completed, one can coagulate the bleeding points and remove the clips if necessary.

Rule three: Cover all the visible cortex with soft, wet gauze and place a long strip of soft gauze from the edge of the visible cyst to the receptacle which is supposed to receive it intact. Pack the cortex-dura interface with wet gauze to prevent an accidental flood with hydatid fluid from seeping around the cortex and finding its way toward the base of the brain.

Rule four: Enlarge the cortical opening over the cyst using episiotomies in safe directions and excise the pericyst which is quite thin but may impair the normal delivery of the cyst. The pericyst is always present but is translucent and may be difficult to see. It often ruptures spontaneously. The unaware surgeon may believe the ectocyst is starting to rupture.

Rule five: Imbibe all the surrounding gauze with 0.1 % cetrimide solution and in case of rupture irrigate the entire field with the cetrimide solution before and after removing the surrounding gauze. Cetrimide in this concentration is innocuous to the brain but is a powerful scolicidal solution (Frayha et al. 1981; Frayha et al. 1997). Do not use hypertonic saline and certainly not formalin. The use of formalin may be fatal (Kocaman et al. 1999).

If these five rules are followed, the possibility of intact delivery of the cyst is enhanced, and, in case of rupture, recurrences are reduced to a very low percentage.

Cystoperitoneal Shunt

Peter et al. (1994) mention the insertion of a “cystoperitoneal” shunt as an emergency “by a resident.” The cyst was removed a year later together with the shunt and the patient developed abdominal cysts.

Cysto-Atrial Shunt

El-Khamlichi et al. (1980) report a case, erroneously diagnosed as an intra-axial tumor, who underwent a cysto-atrial shunt and who developed an infection and meningitis followed by death, and it was on autopsy that the real nature of the disease was discovered.

Anaphylactic Shock

Much has been said and written about anaphylactic shock, especially in case of cyst rupture during surgery; yet there are very few case reports relating to this condition. De Durana et al. (1997) report on a male who was seen in the emergency department with urticaria, angioedema, syncope, and severe hypotension with positive hydatid serological tests, a year prior to the appearance of a cerebral cyst on computed tomography of the brain. It is difficult to accept any cause and effect of these reactions to the cerebral cyst. Kaya et al. (1975) report on a case that died 1 day after surgery, where “the hydatid fluid spilled into the subarachnoid space during the removal of the parapontine cyst; hyperthermia and severe allergic reactions were noted and death was probably due to anaphylactic shock.” The authors of the article themselves are in doubt about anaphylactic shock and use the term “probably.” Turgut (2001), who reviewed 47 articles in the Turkish literature, collected three deaths from “anaphylactic shock” out of 268 cases but does not describe the facts.

Complications Related to Nonsurgical Treatment

Albendazole and Mebendazole Treatment

If given for a long period of time, they may produce mild to moderate rise in the level of liver enzymes, alopecia, and bone marrow suppression. All these complications are reversible upon the cessation of treatment (Nourbakhsh et al. 2010).

Praziquantel Treatment

I have no experience with this drug and could not find except one reference related to the complications of this drug in humans by Zhang and Zhang (2011) who report on a case of recrudescence of fever following the treatment with this drug. I refer here to Chap. 16 of this book where the authors Dlamini and Ntusi state that “Praziquantel is usually well-tolerated.” It may cause abdominal discomfort and nausea. Dizziness, fever, headache, seizures, and malaise have been described. Less commonly, the drug may cause hepatotoxicity, ventricular fibrillation, atrioventricular block, ventricular ectopy, and hypersensitivity.

Complications During the Postoperative Period

Some of these complications are specific to hydatid disease, and others are common to all other craniotomies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree