Contributions of the Sociocultural Sciences

3.1 Sociobiology and Ethology

3.1 Sociobiology and Ethology

SOCIOBIOLOGY

The term sociobiology was coined in 1975 by Edward Osborne Wilson, an American biologist whose book, which is called Sociobiology, emphasized the role of evolution in shaping behavior. Sociobiology is the study of human behavior based on the transmission and modification of genetically influenced behavioral traits. It explores the ultimate question of why specific behaviors or other phenotypes came to be.

EVOLUTION

Evolution is described as any change in the genetic makeup of a population. It is the foundational paradigm from which all of biology arises. It unites ethology, population biology, ecology, anthropology, game theory, and genetics. Charles Darwin (1809–1882) posited that natural selection operates via differential reproduction, in a competitive environment, whereby certain individuals are more successful than others. Given that differences among individuals are at least somewhat heritable, any comparative advantage will result in a gradual redistribution of traits in succeeding generations, such that favored characteristics will be represented in greater proportion over time. In Darwin’s terminology, fitness meant reproductive success.

Competition. Animals vie with one another for resources and territory, the area that is defended for the exclusive use of the animal and that ensures access to food and reproduction. The ability of one animal to defend a disputed territory or resource is called resource holding potential, and the greater this potential, the more successful the animal.

Aggression. Aggression serves both to increase territory and to eliminate competitors. Defeated animals can emigrate, disperse, or remain in the social group as subordinate animals. A dominance hierarchy in which animals are associated with one another in subtle but well-defined ways is part of every social pattern.

Reproduction. Because behavior is influenced by heredity, those behaviors that promote reproduction and survival of the species are among the most important. Men tend to have a higher variance in reproductive success than do women, thus inclining men to be competitive with other men. Male–male competition can take various forms; for example, sperm can be thought of as competing for access to the ovum. Competition among women, although genuine, typically involves social undermining rather than overt violence. Sexual dimorphism, or different behavioral patterns for males and females, evolves to ensure the maintenance of resources and reproduction.

Altruism. Altruism is defined by sociobiologists as a behavior that reduces the personal reproductive success of the initiator while increasing that of the recipient. According to traditional Darwinian theory, altruism should not occur in nature because, by definition, selection acts against any trait whose effect is to decrease its representation in future generations; and yet, an array of altruistic behaviors occurs among free-living mammals as well as humans. In a sense, altruism is selfishness at the level of the gene rather than at the level of the individual animal. A classic case of altruism is the female worker classes of certain wasps, bees, and ants. These workers are sterile and do not reproduce but labor altruistically for the reproductive success of the queen.

Another possible mechanism for the evolution of altruism is group selection. If groups containing altruists are more successful than those composed entirely of selfish members, the altruistic groups succeed at the expense of the selfish ones, and altruism evolves. But within each group, altruists are at a severe disadvantage relative to selfish members, however well the group as a whole does.

Implications for Psychiatry. Evolutionary theory provides possible explanations for some disorders. Some may be manifestations of adaptive strategies. For example, cases of anorexia nervosa may be partially understood as a strategy ultimately caused to delay mate selection, reproduction, and maturation in situations where males are perceived as scarce. Persons who take risks may do so to obtain resources and gain social influence. An erotomanic delusion in a postmenopausal single woman may represent an attempt to compensate for the painful recognition of reproductive failure.

Studies of Identical Twins Reared Apart: Nature versus Nurture

Studies in sociobiology have stimulated one of the oldest debates in psychology. Does human behavior owe more to nature or to nurture? Curiously, humans readily accept the fact that genes determine most of the behaviors of nonhumans, but tend to attribute their own behavior almost exclusively to nurture. In fact, however, recent data unequivocally identify our genetic endowment as an equally important, if not more important, factor.

The best “experiments of nature” permitting an assessment of the relative influences of nature and nurture are cases of genetically identical twins separated in infancy and raised in different social environments. If nurture is the most important determinant of behavior, they should behave differently. On the other hand, if nature dominates, each will closely resemble the other, despite their never having met. Several hundred pairs of twins separated in infancy, raised in separate environments, and then reunited in adulthood have been rigorously analyzed. Nature has emerged as a key determinant of human behavior.

Laura R and Catherine S were reunited at the age of 35. They were identical twins that had been adopted by two different families in Chicago. Growing up, neither twin was aware of the other’s existence. As children each twin had a cat named Lucy, and both habitually cracked their knuckles. Laura and Catherine each began to have migraine headaches beginning at the age of 14. Both were elected valedictorian of their high school classes and majored in journalism in college. Each sister had married a man named John and had given birth to a daughter in wedlock. Both of their marriages fell apart within two years. Each twin maintained a successful rose garden and took morning spin classes at their local fitness center. Upon meeting, each twin discovered that the other had also named her daughter Erin and owned a German Sheppard named Rufus. They had similar voices, hand gestures, and mannerisms.

Jack Y and Oskar S, identical twins born in Trinidad in 1933 and separated in infancy by their parents’ divorce, were first reunited at age 46. Oskar was raised by his Catholic mother and grandmother in Nazi-occupied Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia. Jack was raised by his Orthodox Jewish father in Trinidad and spent time on an Israeli kibbutz. Each wore aviator glasses and a blue sport shirt with shoulder plackets, had a trim mustache, liked sweet liqueurs, stored rubber bands on his wrists, read books and magazines from back to front, dipped buttered toast in his coffee, flushed the toilet before and after using it, enjoyed sneezing loudly in crowded elevators to frighten other passengers, and routinely fell asleep at night while watching television. Each was impatient, squeamish about germs, and gregarious.

Bessie and Jessie, identical twins separated at 8 months of age after their mother’s death, were first reunited at age 18. Each had had a bout of tuberculosis, and they had similar voices, energy levels, administrative talents, and decision-making styles. Each had had her hair cut short in early adolescence. Jessie had a college-level education, whereas Bessie had had only 4 years of formal education; yet Bessie scored 156 on intelligence quotient testing and Jessie scored 153. Each read avidly, which may have compensated for Bessie’s sparse education; she created an environment compatible with her inherited potential.

Neuropsychological Testing Results

A dominant influence of genetics on behavior has been documented in several sets of identical twins on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Twins reared apart generally showed the same degree of genetic influence across the different scales as twins reared together. Two particularly fascinating identical twin pairs, despite being reared on different continents, in countries with different political systems and different languages, generated scores more closely correlated across 13 MMPI scales than the already tight correlation noted among all tested identical twin pairs, most of whom had shared similar rearing.

Reared-apart twin studies report a high correlation (r = 0.75) for intelligence quotient (IQ) similarity. In contrast, the IQ correlation for reared-apart nonidentical twin siblings is 0.38, and for sibling pairs in general, is in the 0.45 to 0.50 range. Strikingly, IQ similarities are not influenced by similarities in access to dictionaries, telescopes, and original artwork; in parental education and socioeconomic status; or in characteristic parenting practices. These data overall suggest that tested intelligence is determined roughly two thirds by genes and one third by environment.

Studies of reared-apart identical twins reveal a genetic influence on alcohol use, substance abuse, childhood antisocial behavior, adult antisocial behavior, risk aversion, and visuomotor skills, as well as on psychophysiological reactions to music, voices, sudden noises, and other stimulation, as revealed by brain wave patterns and skin conductance tests. Moreover, reared-apart identical twins show that genetic influence is pervasive, affecting virtually every measured behavioral trait. For example, many individual preferences previously assumed to be due to nurture (e.g., religious interests, social attitudes, vocational interests, job satisfaction, and work values) are strongly determined by nature.

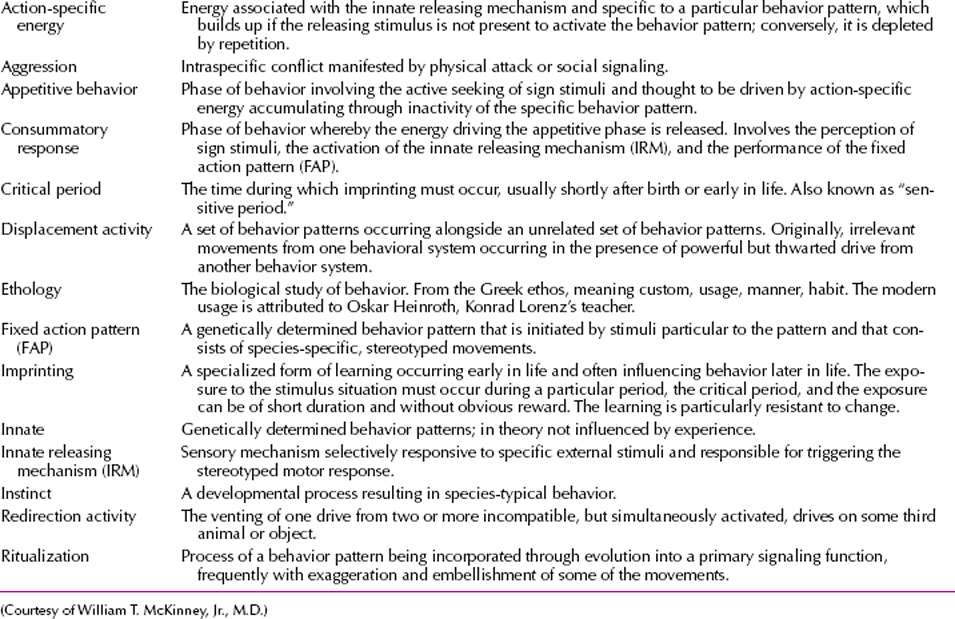

A selected glossary of some terms used in this section and other ethological terms is given in Table 3.1-1.

Table 3.1-1

Table 3.1-1

Selected Glossary of Ethological Terms

ETHOLOGY

The systematic study of animal behavior is known as ethology. In 1973 the Nobel Prize in psychiatry and medicine was awarded to three ethologists, Karl von Frisch, Konrad Lorenz, and Nikolaas Tinbergen. Those awards highlighted the special relevance of ethology, not only for medicine, but also for psychiatry.

Konrad Lorenz

Born in Austria, Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989) is best known for his studies of imprinting. Imprinting implies that, during a certain short period of development, a young animal is highly sensitive to a certain stimulus that then, but not at other times, provokes a specific behavior pattern. Lorenz described newly hatched goslings that are programmed to follow a moving object and thereby become imprinted rapidly to follow it and, possibly, similar objects. Typically, the mother is the first moving object the gosling sees, but should it see something else first, the gosling follows it. For instance, a gosling imprinted by Lorenz followed him and refused to follow a goose (Fig. 3.1-1). Imprinting is an important concept for psychiatrists to understand in their effort to link early developmental experiences with later behaviors.

FIGURE 3.1-1

In a famous experiment, Konrad Lorenz demonstrated that goslings responded to him as if he were the natural mother. (Reprinted from Hess EH. Imprinting: An effect of an early experience. Science. 1959;130:133, with permission.)

Lorenz is also well known for his study of aggression. He wrote about the practical function of aggression, such as territorial defense by fish and birds. Aggression among members of the same species is common, but Lorenz pointed out that in normal conditions, it seldom leads to killing or even to serious injury. Although animals attack one another, a certain balance appears between tendencies to fight and flight, with the tendency to fight being strongest in the center of the territory and the tendency to flight strongest at a distance from the center.

In many works, Lorenz tried to draw conclusions from his ethological studies of animals that could also be applied to human problems. The postulation of a primary need for aggression in humans, cultivated by the pressure for selection of the best territory, is a primary example. Such a need may have served a practical purpose at an early time, when humans lived in small groups that had to defend themselves from other groups. Competition with neighboring groups could become an important factor in selection. Lorenz pointed out, however, that this need has survived the advent of weapons that can be used not merely to kill individuals but to wipe out all humans.

Nikolaas Tinbergen

Born in the Netherlands, Nikolaas Tinbergen (1907–1988), a British zoologist, conducted a series of experiments to analyze various aspects of animal behavior. He was also successful in quantifying behavior and in measuring the power or strength of various stimuli in eliciting specific behavior. Tinbergen described displacement activities, which have been studied mainly in birds. For example, in a conflict situation, when the needs for fight and for flight are of roughly equal strength, birds sometimes do neither. Rather, they display behavior that appears to be irrelevant to the situation (e.g., a herring gull defending its territory can start to pick grass). Displacement activities of this kind vary according to the situation and the species concerned. Humans can engage in displacement activities when under stress.

Lorenz and Tinbergen described innate releasing mechanisms, animals’ responses triggered by releasers, which are specific environmental stimuli. Releasers (including shapes, colors, and sounds) evoke sexual, aggressive, or other responses. For example, big eyes in human infants evoke more caretaking behavior than do small eyes.

In his later work, Tinbergen, along with his wife, studied early childhood autistic disorder. They began by observing the behavior of autistic and normal children when they meet strangers, analogous to the techniques used in observing animal behavior. In particular, they observed in animals the conflict that arises between fear and the need for contact and noted that the conflict can lead to behavior similar to that of autistic children. They hypothesized that, in certain predisposed children, fear can greatly predominate and can also be provoked by stimuli that normally have a positive social value for most children. This innovative approach to studying infantile autistic disorder opened up new avenues of inquiry. Although their conclusions about preventive measures and treatment must be considered tentative, their method shows another way in which ethology and clinical psychiatry can relate to each other.

Karl von Frisch

Born in Austria, Karl von Frisch (1886–1982) conducted studies on changes of color in fish and demonstrated that fish could learn to distinguish among several colors and that their sense of color was fairly congruent with that of humans. He later went on to study the color vision and behavior of bees and is most widely known for his analysis of how bees communicate with one another—that is, their language, or what is known as their dances. His description of the exceedingly complex behavior of bees prompted an investigation of communication systems in other animal species, including humans.

Characteristics of Human Communication

Communication is traditionally seen as an interaction in which a minimum of two participants—a sender and a receiver—share the same goal: the exchange of accurate information. Although shared interest in accurate communication remains valid in some domains of animal signaling—notably such well-documented cases as the “dance of the bees,” whereby foragers inform other workers about the location of food sources—a more selfish and, in the case of social interaction, more accurate model of animal communication has largely replaced this concept.

Sociobiological analyses of communication emphasize that because individuals are genetically distinct, their evolutionary interests are similarly distinct, although admittedly with significant fitness overlap, especially among kin, reciprocators, parents and offspring, and mated pairs. Senders are motivated to convey information that induces the receivers to behave in a manner that enhances the senders’ fitness. Receivers, similarly, are interested in responding to communication only insofar as such response enhances their own fitness. One important way to enhance reliability is to make the signal costly; for example, an animal could honestly indicate its physical fitness, freedom from parasites and other pathogens, and possibly its genetic quality as well by growing elaborate and metabolically expensive secondary sexual characteristics such as the oversized tail of a peacock. Human beings, similarly, can signal their wealth by conspicuous consumption. This approach, known as the handicap principle, suggests that effective communication may require that the signaler engage in especially costly behavior to ensure success.

SUBHUMAN PRIMATE DEVELOPMENT

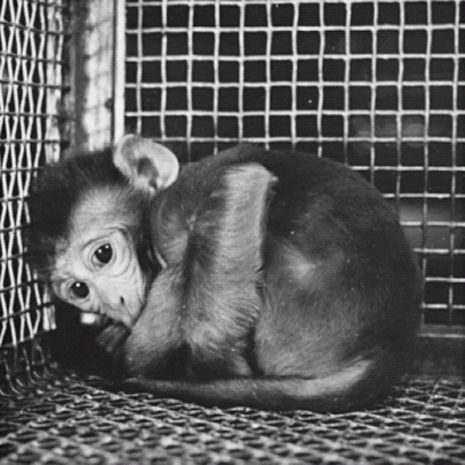

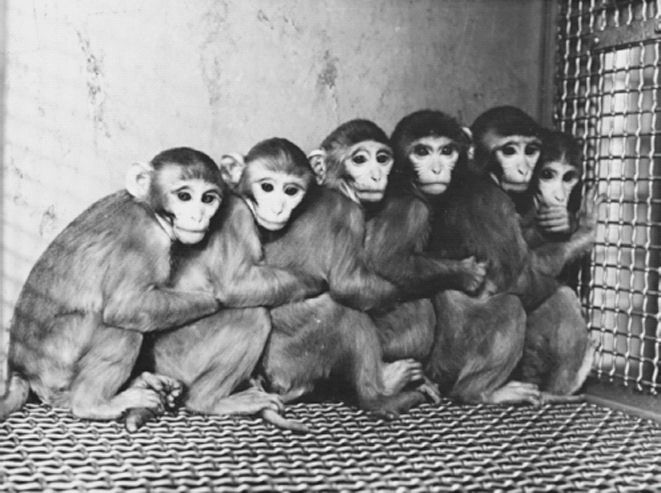

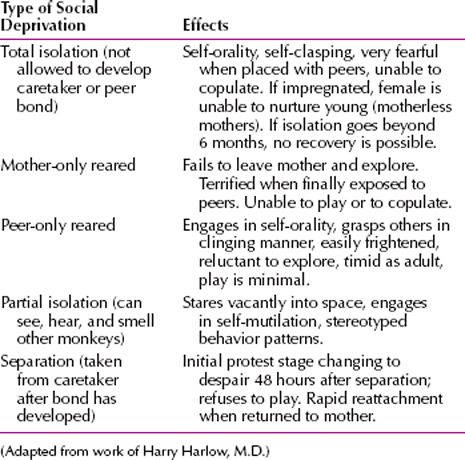

An area of animal research that has relevance to human behavior and psychopathology is the longitudinal study of nonhuman primates. Monkeys have been observed from birth to maturity, not only in their natural habitats and laboratory facsimiles but also in laboratory settings that involve various degrees of social deprivation early in life. Social deprivation has been produced through two predominant conditions: social isolation and separation. Socially isolated monkeys are raised in varying degrees of isolation and are not permitted to develop normal attachment bonds. Monkeys separated from their primary caretakers thereby experience disruption of an already developed bond. Social isolation techniques illustrate the effects of an infant’s early social environment on subsequent development (Figs. 3.1-2 and 3.1-3), and separation techniques illustrate the effects of loss of a significant attachment figure. The name most associated with isolation and separation studies is Harry Harlow. A summary of Harlow’s work is presented in Table 3.1-2.

FIGURE 3.1-2

Social isolate after removal of isolation screen.

FIGURE 3.1-3

Choo-choo phenomenon in peer-only-reared infant rhesus monkeys.

Table 3.1-2

Table 3.1-2

Social Deprivation in Nonhuman Primates

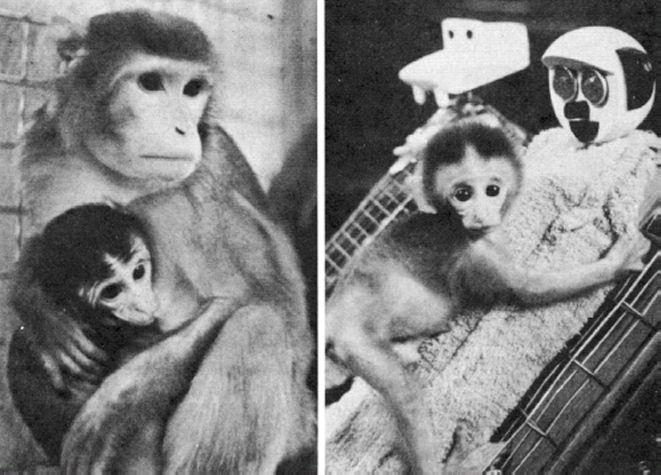

In a series of experiments, Harlow separated rhesus monkeys from their mothers during their first weeks of life. During this time, the monkey infant depends on its mother for nourishment and protection, as well as for physical warmth and emotional security—contact comfort, as Harlow first termed it in 1958. Harlow substituted a surrogate mother made from wire or cloth for the real mother. The infants preferred the cloth-covered surrogate mother, which provided contact comfort, to the wire-covered surrogate, which provided food but no contact comfort (Fig. 3.1-4).

FIGURE 3.1-4

Monkey infant with mother (left) and with cloth-covered surrogate (right).

Treatment of Abnormal Behavior

Stephen Suomi demonstrated that monkey isolates can be rehabilitated if they are exposed to monkeys that promote physical contact without threatening the isolates with aggression or overly complex play interactions. These monkeys were called therapist monkeys. To fill such a therapeutic role, Suomi chose young normal monkeys that would play gently with the isolates and approach and cling to them. Within 2 weeks, the isolates were reciprocating the social contact, and their incidence of abnormal self-directed behaviors began to decline significantly. By the end of the 6-month therapy period, the isolates were actively initiating play bouts with both the therapists and each other, and most of their self-directed behaviors had disappeared. The isolates were observed closely for the next 2 years, and their improved behavioral repertoires did not regress over time. The results of this and subsequent monkey-therapist studies underscored the potential reversibility of early cognitive and social deficits at the human level. The studies also served as a model for developing therapeutic treatments for socially retarded and withdrawn children.

Several investigators have argued that social separation manipulations with nonhuman primates provide a compelling basis for animal models of depression and anxiety. Some monkeys react to separations with behavioral and physiological symptoms similar to those seen in depressed human patients; both electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and tricyclic drugs are effective in reversing the symptoms in monkeys. Not all separations produce depressive reactions in monkeys, just as separation does not always precipitate depression in humans, young and old.

Individual Differences

Recent research has revealed that some rhesus monkey infants consistently display fearfulness and anxiety in situations in which similarly reared peers show normal exploratory behavior and play. These situations generally involve exposure to a novel object or situation. Once the object or situation has become familiar, any behavioral differences between the anxiety-prone, or timid, infants and their outgoing peers disappear, but the individual differences appear to be stable during development. Infant monkeys at 3 to 6 months of age that are at high risk for fearful or anxious reactions tend to remain at high risk for such reactions, at least until adolescence.

Long-term follow-up study of these monkeys has revealed some behavioral differences between fearful and nonfearful female monkeys when they become adults and have their first infants. Fearful female monkeys who grow up in socially benign and stable environments typically become fine mothers, but fearful female monkeys who have reacted with depression to frequent social separations during childhood are at high risk for maternal dysfunction; more than 80 percent of these mothers either neglect or abuse their first offspring. Yet nonfearful female monkeys that encounter the same number of social separations but do not react to any of these separations with depression turn out to be good mothers.

EXPERIMENTAL DISORDERS

Stress Syndromes

Several researchers, including Ivan Petrovich Pavlov in Russia and W. Horsley Gantt and Howard Scott Liddell in the United States, studied the effects of stressful environments on animals, such as dogs and sheep. Pavlov produced a phenomenon in dogs, which he labeled experimental neurosis, by the use of a conditioning technique that led to symptoms of extreme and persistent agitation. The technique involved teaching dogs to discriminate between a circle and an ellipse and then progressively diminishing the difference between the two. Gantt used the term behavior disorders to describe the reactions he elicited from dogs forced into similar conflictual learning situations. Liddell described the stress response he obtained in sheep, goats, and dogs as experimental neurasthenia, which was produced in some cases by merely doubling the number of daily test trials in an unscheduled manner.

Learned Helplessness

The learned helplessness model of depression, developed by Martin Seligman, is a good example of an experimental disorder. Dogs were exposed to electric shocks from which they could not escape. The dogs eventually gave up and made no attempt to escape new shocks. The apparent giving up generalized to other situations, and eventually the dogs always appeared to be helpless and apathetic. Because the cognitive, motivational, and affective deficits displayed by the dogs resembled symptoms common to human depressive disorders, learned helplessness, although controversial, was proposed as an animal model of human depression. In connection with learned helplessness and the expectation of inescapable punishment, research on subjects has revealed brain release of endogenous opiates, destructive effects on the immune system, and elevation of the pain threshold.

A social application of this concept involves schoolchildren who have learned that they fail in school no matter what they do; they view themselves as helpless losers, and this self-concept causes them to stop trying. Teaching them to persist may reverse the process, with excellent results in self-respect and school performance.

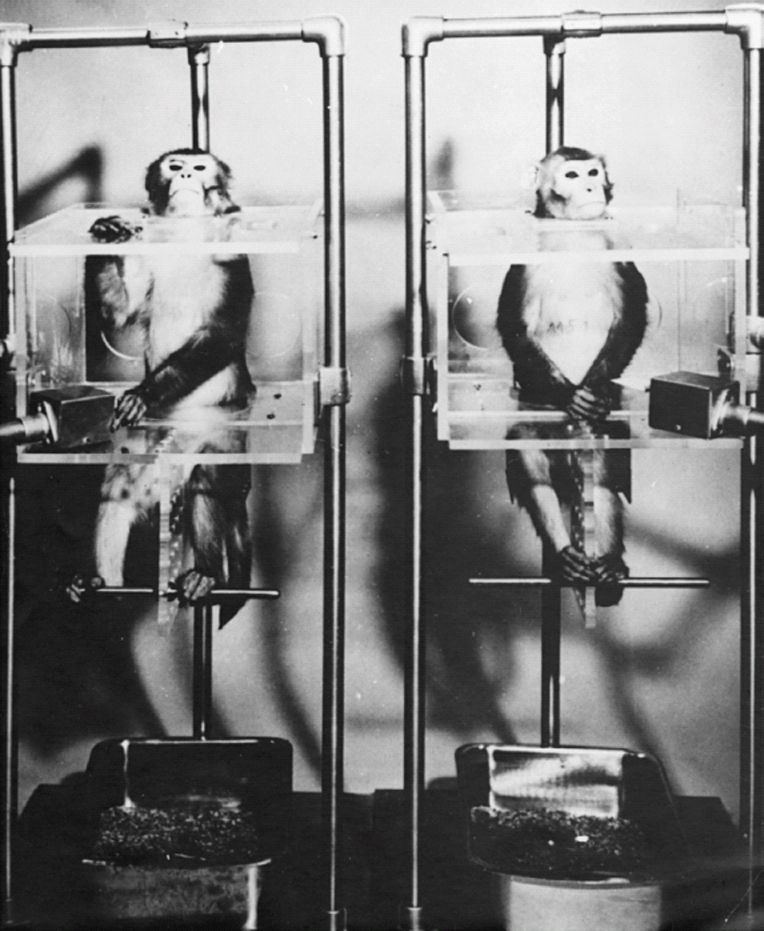

Unpredictable Stress

Rats subjected to chronic unpredictable stress (crowding, shocks, irregular feeding, and interrupted sleep time) show decreases in movement and exploratory behavior; this finding illustrates the roles of unpredictability and lack of environmental control in producing stress. These behavioral changes can be reversed by antidepressant medication. Animals under experimental stress (Fig. 3.1-5) become tense, restless, hyperirritable, or inhibited in certain conflict situations.

FIGURE 3.1-5

The monkey on the left, known as the executive monkey, controls whether both will receive an electric shock. The decision-making task produces a state of chronic tension. Note the more relaxed attitude of the monkey on the right. (From U.S. Army photographs, with permission.)

Dominance

Animals in a dominant position in a hierarchy have certain advantages (e.g., in mating and feeding). Being more dominant than peers is associated with elation, and a fall in position in the hierarchy is associated with depression. When persons lose jobs, are replaced in organizations, or otherwise have their dominance or hierarchical status changed, they can experience depression.

Temperament

Temperament mediated by genetics plays a role in behavior. For example, one group of pointer dogs was bred for fearfulness and a lack of friendliness toward persons, and another group was bred for the opposite characteristics. The phobic dogs were extremely timid and fearful and showed decreased exploratory capacity, increased startle response, and cardiac arrhythmias. Benzodiazepines diminished these fearful, anxious responses. Amphetamines and cocaine aggravated the responses of genetically nervous dogs to a greater extent than they did the responses of the stable dogs.

Brain Stimulation

Pleasurable sensations have been produced in both humans and animals through self-stimulation of certain brain areas, such as the medial forebrain bundle, the septal area, and the lateral hypothalamus. Rats have engaged in repeated self-stimulation (2,000 stimulations per hour) to gain rewards. Catecholamine production increases with self-stimulation of the brain area, and drugs that decrease catecholamines decrease the process. The centers for sexual pleasure and opioid reception are closely related anatomically. Heroin addicts report that the so-called rush after intravenous injection of heroin is akin to an intense sexual orgasm.

Pharmacological Syndromes

With the emergence of biological psychiatry, many researchers have used pharmacological means to produce syndrome analogs in animal subjects. Two classic examples are the reserpine (Serpasil) model of depression and the amphetamine psychosis model of paranoid schizophrenia. In the depression studies, animals given the norepinephrine-depleting drug reserpine exhibited behavioral abnormalities analogous to those of major depressive disorder in humans. The behavioral abnormalities produced were generally reversed by antidepressant drugs. These studies tended to corroborate the theory that depression in humans is, in part, the result of diminished levels of norepinephrine. Similarly, animals given amphetamines acted in a stereotypical, inappropriately aggressive, and apparently frightened manner that resembled paranoid psychotic symptoms in humans. Both of these models are considered too simplistic in their concepts of cause, but they remain as early paradigms for this type of research.

Studies have also been done on the effects of catecholamine-depleting drugs on monkeys during separation and reunion periods. These studies showed that catecholamine depletion and social separation can interact in a highly synergistic fashion and can yield depressive symptoms in subjects for whom mere separation or low-dose treatment by itself does not suffice to produce depression.

Reserpine has produced severe depression in humans and, as a result, is rarely used as either an antihypertensive (its original indication) or an antipsychotic. Similarly, amphetamine and its congeners (including cocaine) can induce psychotic behavior in persons who use it in overdose or over long periods of time.

SENSORY DEPRIVATION

The history of sensory deprivation and its potentially deleterious effects evolved from instances of aberrant mental behavior in explorers, shipwrecked sailors, and prisoners in solitary confinement. Toward the end of World War II, startling confessions, induced by brainwashing prisoners of war, caused a rise of interest in this psychological phenomenon brought about by the deliberate diminution of sensory input.

To test the hypothesis that an important element in brainwashing is prolonged exposure to sensory isolation, D. O. Hebb and his coworkers brought solitary confinement into the laboratory and demonstrated that volunteer subjects—under conditions of visual, auditory, and tactile deprivation for periods of up to 7 days—reacted with increased suggestibility. Some subjects also showed characteristic symptoms of the sensory deprivation state: anxiety, tension, inability to concentrate or organize thoughts, increased suggestibility, body illusions, somatic complaints, intense subjective emotional distress, and vivid sensory imagery—usually visual and sometimes reaching the proportions of hallucinations with a delusionary quality.

Psychological Theories

Anticipating psychological explanation, Sigmund Freud wrote: “It is interesting to speculate what could happen to ego function if the excitations or stimuli from the external world were either drastically diminished or repetitive. Would there be an alteration in the unconscious mental processes and an effect upon the conceptualization of time?”

Indeed, under conditions of sensory deprivation, the abrogation of such ego functions as perceptual contact with reality and logical thinking brings about confusion, irrationality, fantasy formation, hallucinatory activity, and wish-dominated mental reactions. In the sensory-deprivation situation, the subject becomes dependent on the experimenter and must trust the experimenter for the satisfaction of such basic needs as feeding, toileting, and physical safety. A patient undergoing psychoanalysis may be in a kind of sensory deprivation room (e.g., a soundproof room with dim lights and a couch) in which primary-process mental activity is encouraged through free association.

Cognitive. Cognitive theories stress that the organism is an information-processing machine, whose purpose is optimal adaptation to the perceived environment. Lacking sufficient information, the machine cannot form a cognitive map against which current experience is matched. Disorganization and maladaptation then result. To monitor their own behavior and to attain optimal responsiveness, persons must receive continuous feedback; otherwise, they are forced to project outward idiosyncratic themes that have little relation to reality. This situation is similar to that of many psychotic patients.

Physiological Theories

The maintenance of optimal conscious awareness and accurate reality testing depends on a necessary state of alertness. This alert state, in turn, depends on a constant stream of changing stimuli from the external world, mediated through the ascending reticular activating system in the brainstem. In the absence or impairment of such a stream, as occurs in sensory deprivation, alertness drops away, direct contact with the outside world diminishes, and impulses from the inner body and the central nervous system may gain prominence. For example, idioretinal phenomena, inner ear noise, and somatic illusions may take on a hallucinatory character.

REFERENCES

Burghardt GM. Darwin’s legacy to comparative psychology and ethology. Am Psychologist. 2009; 64(2):102.

Burt A, Trivers R. Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press; 2006.

Confer JC, Easton JA, Fleischman DS, Goetz CD, Lewis DMG, Perilloux C, Buss DM. Evolutionary psychology: Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations. Am Psychologist. 2010;65(2):110.

De Block A, Adriaens PR. Maladapting Minds: Philosophy, Psychiatry, and Evolutionary Theory. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Griffith JL. Neuroscience and humanistic psychiatry: a residency curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;1–8.

Keller MC, Miller G. Resolving the paradox of common, harmful, heritable mental disorders: Which evolutionary genetic models work best? Behav Brain Sci. 2006;29(4):385–405.

Lipton JE, Barash DP. Sociobiology and psychiatry. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:716.

Millon T. Classifying personality disorders: An evolution-based alternative to an evidence-based approach. J Personality Disord. 2011;25(3):279.

van der Horst FCP, Kagan J. John Bowlby – From Psychoanalysis to Ethology: Unravelling the Roots of Attachment Theory. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011.

3.2 Transcultural Psychiatry

3.2 Transcultural Psychiatry

Culture is defined as a set of meanings, norms, beliefs, values, and behavior patterns shared by a group of people. These values include social relationships, language, nonverbal expression of thoughts and emotions, moral and religious beliefs, rituals, technology, and economic beliefs and practices, among other items. Culture has six essential components: (1) Culture is learned; (2) culture can be passed on from one generation to the next; (3) culture involves a set of meanings in which words, behaviors, events, and symbols have meanings agreed upon by the cultural group; (4) culture acts as a template to shape and orient future behaviors and perspectives within and between generations, and to take account of novel situations encountered by the group; (5) culture exists in a constant state of change; and (6) culture includes patterns of both subjective and objective components of human behavior. In addition, culture shapes which and how psychiatric symptoms are expressed; culture influences the meanings that are given to symptoms; and culture affects the interaction between the patient and the health care system, as well as between the patient and the physician and other clinicians with whom the patient and family interact.

Race is a concept, the scientific validity of which is now considered highly questionable, by which human beings are grouped primarily by physiognomy. Its effect on individuals and groups, however, is considerable, due to its reference to physical, biological, and genetic underpinnings, and because of the intensely emotional meanings and responses it generates. Ethnicity refers to the subjective sense of belonging to a group of people with a common national or regional origin and shared beliefs, values, and practices, including religion. It is part of every person’s identity and self-image.

CULTURAL FORMULATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree