Is Addiction About Avoiding Pain or Seeking Reward?

Diverse psychological therapies, spanning the spectrum of psychodynamic to cognitive behavioural, have tended to account for addiction as a manifestation of either psychic disturbance or maladaptive coping strategy, as pointed out in Chapter 1. This has a direct effect on how motivation is understood in the context of addiction: if the goal of addiction is to alleviate emotional negativity or to compensate for perceived personal shortcomings, mitigation in this regard should lead to a good outcome. But what if the addiction has a more autonomous nature, more shaped by seeking pleasure or reward than avoiding pain or distress? Certainly, alleviating distress or surmounting personal difficulties might lead to therapeutic gain. But if addiction is intrinsically about the pursuit of reward the gains might not endure. In terms of conceptualizing, formulating and implementing cognitive and behavioural therapy strategies it is imperative that both therapist and client understand the essence of addiction. Cognitive and behavioural techniques that have evolved to address anxiety and depression, syndromes that are characterized by avoidance, need to be configured differently to address a syndrome that is driven less by emotional negativity and more by compulsive reward seeking.

Early behavioural accounts of addiction pre-empted the view espoused above that addictive behaviour was driven by negative reinforcement epitomized by a desire to avoid withdrawal discomfort. Thus, in attempting to account for the endurance and relapse proclivity in addiction, theorists such as Wikler (1948) focused on the apparently plausible notion that, having adapted or learned to tolerate the presence of a drug, individuals experience distress when the drug is not available at the synaptic level. The resulting dysregulation mobilizes the individual to redress the balance by engaging in drug seeking and taking. More sophisticated versions of withdrawal accounts of addiction have invoked a role for ‘opponent processes’ that interact dynamically with the hedonic or pleasurable outcomes of drug administration (Solomon, 1980; Koob and Le Moal, 1997). Accordingly, repeated use of drugs leads to enduring aberrations or deficits in neural reward mechanisms, both within systems (e.g., the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system) and between systems (e.g., the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and neural systems for regulating stress, both mediated by corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), become maladapted or dysregulated by repeated exposure to drugs of abuse. On cessation of drug use, the resulting anhedonic state increases the likelihood of resumption or relapse. Koob and Le Moal (2005, p. 1443) refer to this as the ‘dark side of addiction’, characterized by ‘chronic irritability, emotional pain, malaise, dysphoria, alexithymia, and loss of motivation for natural rewards’. This, the antithesis of reward or ‘antireward’, provides a powerful context for negative reinforcement that motivates compulsive drug-seeking behaviour and addiction. This anhedonic state might be experienced as ‘authentic’ depression or anxiety by the affected person, and indeed present itself to the psychotherapist as such. In the course of a recent clinical encounter I introduced this idea to a man who had been detoxified from alcohol and was complaining of feeling depressed. He replied that the concept of a ‘dark side’ of addiction implied that there was a ‘bright side’. Ironically perhaps, from a neurocognitive perspective there is, or at least was, a ‘bright side’, although perhaps forgotten by the client.

How Formulation Can Go Astray

More generally, the negative affect carried over from acute intoxication represents a potential pitfall in terms of formulation from a cognitive therapy perspective. The clinician might, for instance, search for prior learning experiences in the client’s narrative such as invalidation from attachment figures or traumatic exposure. This quest could be in vain, as the negative affect could reflect the enduring allostatic state rather than the expression of adversity in earlier life or other candidate vulnerability factors. Because current mood is depressed or anxious—regardless of the cause—autobiographical memory is biased accordingly. This leads to a distorted picture emerging on initial assessment. A valid and reliable assessment of a person’s emotional or affective state is thus likely to be confounded by current or recent intensive substance use. In my own clinical experience, and despite awareness of the possibility of this interaction, I still experience the occasional (pleasant!) surprise of a client showing dramatic improvement in affect once substance misuse ceases. Conversely, I have met with few, if any, positive results when addressing concurrent mental health problems such as OCD and depression with clients on opiate substitution or significant drug or alcohol involvement.

Incentive Theories of Addiction

Withdrawal-based accounts struggle to account for the resumption of addiction, sometimes many years after quitting. For example, Gerald, a 70-year-old man, was recently referred to me. The reason for the referral was that Gerald was using crack cocaine on a daily basis. He was spending about £70 each day. Gerald was an amiable man who had worked successfully in the advertising industry, where he had first encountered cocaine when in his 30s. He had made several attempts to give up; the most successful had ended 18 months earlier after 13 years of abstinence. Leading up to resuming cocaine use he recalled thinking ‘I’m bored’. His drug taking quickly became habitual once again and his reflection was ‘I’m still amazed that I carry on doing something when I don’t even like it’. There is now abundant evidence suggesting that it is the capacity for drugs to activate dopaminergic transmission that invests them with such enduring potency (see for example Volkow et al., 2002). Some drugs, such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine and ecstasy, appear to increase dopamine levels more directly by either facilitating dopamine release or inhibiting reuptake. Other drugs, such as alcohol, nicotine, opiates and marijuana, stimulate GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons that culminate in increased levels of dopamine mainly by disrupting reuptake.

Further, the unnatural surge in dopamine levels elicited by drug ingestion can drain normal rewards of their dopaminergic potency. Schultz (2002) pointed out that drugs directly target neural reward-processing centres, in contrast to natural rewards such as food or water. This results in elevation of dopamine levels in areas such as the nucleus accumbens that is significantly greater than that elicited by conventional rewards. Crucially, this dopamine release consolidates associative learning. It appears, therefore, that exposure to the reinforcing effects of drugs can activate elementary learning mechanisms from the outset. Contingent dopamine release reinforces the preceding instrumental behaviour and invests associated cues with motivational properties through classical conditioning mechanisms. In turn, these elementary learning mechanisms recruit cognitive control processes such as selective attention. In habituated drug takers, this chemical cascade appears to create a motivational state subjectively experienced, according to Everitt and Robbins (2005), as ‘must do!’. In Gerald’s case this proved to be enduring. As will be seen below, drug ingestion does not generally comply with Maslow’s (1943) dictum ‘a satisfied need is not a motivator of behaviour’. Conversely, rather than providing satiation, exposure to drug effects triggers a cycle of craving, intoxication, withdrawal and further binging.

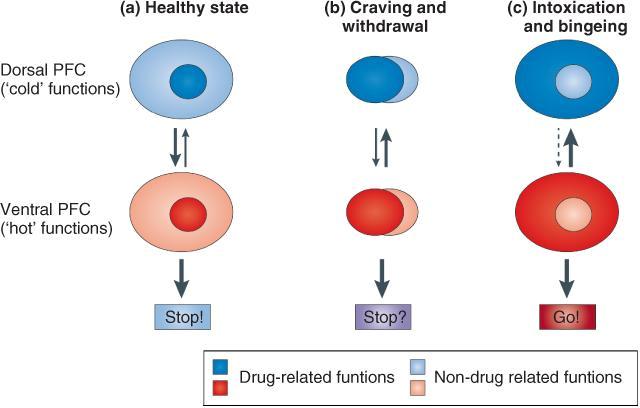

The cognitive and motivational dynamics of addiction have been elegantly captured in the impaired Response Inhibition and Salience Attribution (iRISA) framework (Goldstein and Volkow, 2002). In this model, substance and substance-related cues acquire increased salience while non-drug reinforcers become less prominent during cycles of regimented drug taking, bingeing or withdrawal. Parallel with this, the ability to inhibit drug seeking and taking and other maladaptive behaviours is impaired. Inhibitory processes are predicated on dorsal prefrontal cortex (PFC) subregions such as the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), the inferior frontal gyrus and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC). Incentive salience and consequential drug wanting, attention bias and drug seeking are subserved by regions such as the medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), the ventromedial PFC and rostroventral ACC (see Goldstein and Volkow, 2011) (Figure 3.1). In the normal, non-addicted, non-intoxicated state, here represented by the light-gray ovals (Figure 3.1(a)), cognitive control is maintained by dorsal PFC regions. This suppresses the ‘hot’, more ventral PFC functions, here represented by the dark gray ovals, that drive not just impulses for drug seeking but emotions for fear, anger or sexual desire. During cue reactivity (Figure 3.1(b)), when craving or withdrawal may be elicited, drug-related cognitive processes, behaviours and emotions challenge cognitive control, inducing approach–avoidance conflict. Intoxication and bingeing occur when cognitive control is impaired (Figure 3.1(c)).

Learning Mechanisms in Addiction

Both classical (stimulus–stimulus) and operant (stimulus–response) learning mechanisms have been invoked to account for the acquisition of addictive behaviour. The former controls behaviour by means of antecedent cues and the latter by the ‘value’ or utility attached to the outcome. Drawing on animal laboratory work, Yin and Knowlton (2006, p. 167) described how classical and operant processes operating in tandem can lead to addictive behaviour:

1. Stimulus–outcome (S-O) association. Laboratory or environmental cues elicit preparatory responses (as in the classic Pavlovian salivation response) in anticipation of a biologically relevant outcome or unconditional response. Essentially, what is conditioned or learned is which cues predict which outcomes. This type of learning is relatively insensitive to subsequent manipulation of the action–outcome relationship see (A-O contingency, below) or ‘reward devaluation’, particularly when the outcome is delivery of a drug that activates neural reward circuitry. In other words the behaviour—drug seeking and use—perseveres even when the outcome is adverse or at least not leading to the delivery of the anticipated or expected reward. This might shed light on the disappointing results often found with exposure paradigms (see Conklin and Tiffany, 2002) that entail exposure to the reward signal but withholding of the expected reward or source of gratification. Despite the hoped-for deconditioning process, the cue—perhaps the sight and smell of a favourite alcoholic beverage—retains its incentive value and the capacity to trigger drug seeking. It is the cue rather than the delivery of the reward that has the power to activate neural reward mechanisms. Thus, O’Doherty et al. (2002) found that midbrain neural reward mechanisms were activated by the presentation of cues predicting a pleasant taste rather than the subsequent delivery of the drop of glucose.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree