Cranial Dural Vascular Malformations

Key Points

The physiologic impact of dural arteriovenous malformations (DAVMs) is determined almost exclusively by the pattern of venous drainage.

Treatment of DAVMs must strive to preserve normal parenchymal venous drainage in order to avoid complications of venous infarction and venous hypertension.

Vascular malformations or fistulas of the dura are uncommon diseases, but they have the potential to develop severe complications. They account for 10% to 15% of intracranial arteriovenous malformations of all types. They can occur in the brain or spine (Chapter 21) with characteristic patterns of pathophysiology in both locations.

The cranial dura consists of two tightly apposed layers, an outer periosteal layer and an inner meningeal layer, separated by a rich vascular layer of meningeal or dural veins and arterioles. Where the two layers of dura become separated, a larger venous space forms the dural sinuses. Along the cranial dura, any meningeal artery that perforates the dura usually does so in close relationship to surrounding venous plexuses. The artery penetrates the dura through or may run for a while within a venous structure or sinus. Venous thrombosis or other injuries, including surgery (1,2,3), may occasion a process of inflammation, neovascularization, and angiogenesis (4). The adjacent arterioles are thought to become involved with the formation of pathologic shunts to venous channels (5). In some instances, the fistulous connection could be the initiating event, as might happen with acute trauma, and the high-flowing lesion is then hypothesized to recruit additional arterial supply through the angiogenic mediators. In most patients, an acquired etiology is certain, in view of well-documented cases of such lesions soon after surgery, trauma, or mastoid air-cell infection. Metachronous formation of dural arteriovenous malformations (DAVMs) has also been seen, supporting the assumption of an acquired etiology (6). Patients with systemic syndromes involving abnormalities of vascular fragility, such as neurofibromatosis type I, fibromuscular dysplasia, and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (7,8,9,10), are reported to be slightly more prone to develop these disorders of the cranial dura or spine.

An acquired dural fistula may be single, multifocal, or complex. The terms DAVMs and dural arteriovenous fistulas are interchangeable and synonymous. Fistulous malformations of the dura can be seen in young children as well. In children, long-standing changes suggest that some rare instances of congenital DAVMs occur.

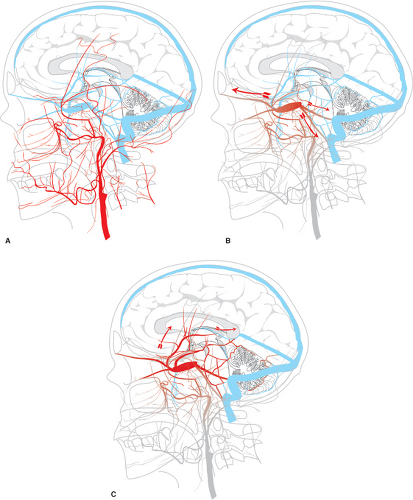

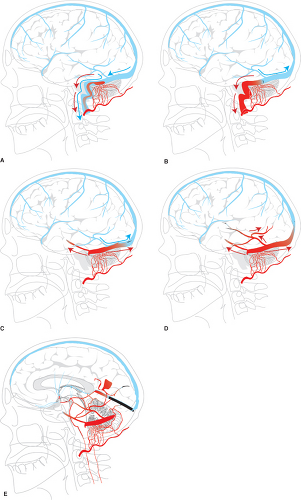

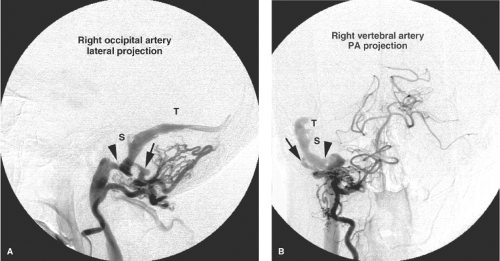

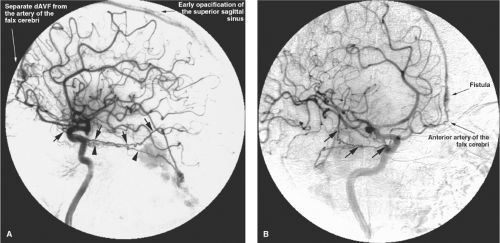

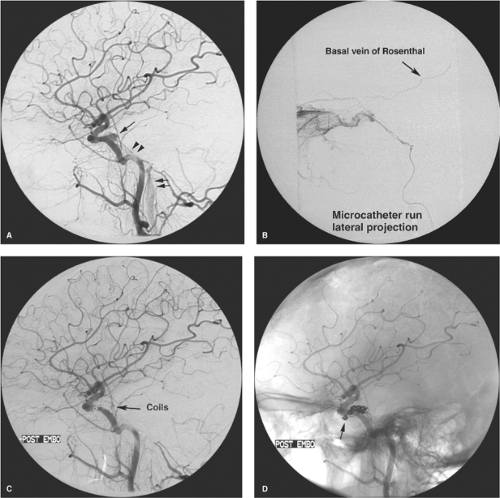

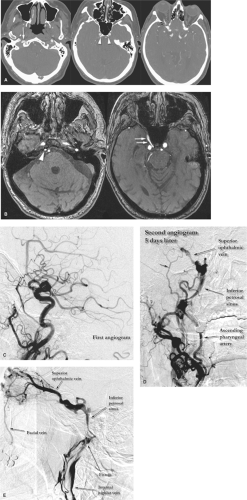

In the cranial dura, the pathophysiology and significance of these lesions derive from their effects on venous flow (Figs. 20-1 and 20-2). Various classification schemes have been proposed to categorize these lesions (11,12,13,14,15,16). The quintessence of all of these schemes is an analysis of the state of disruption of venous outflow from the malformation, and the patency and direction of flow in adjacent dural sinuses, dural veins, and subarachnoid veins. The particular arterial feeders involved with a dural vascular malformation are usually not of primary importance for analysis of risks or treatment options (Figs. 20-3 and 20-4). An interesting classification scheme (16) on the basis of the homologous embryologic origins of segments of dura of the spine and cranium has been proposed with the predictive value that clinical complications are more likely to be seen with certain types, but the process of clinical decision making is not influenced, regardless of the perspective.

Uncomplicated DAVMs are occasionally seen as incidental findings (Fig. 20-5). They may be single or multiple, resulting in arterialization of flow in an orthograde fashion in a major dural sinus. Symptomatic patients present with pulsatile tinnitus, audible bruit, or cranial nerve deficits, depending on location of the lesion. Pulsatile tinnitus may be reported in 20% to 70% of patients, some of whom will volunteer a history of being able to suppress the bruit by manual compression of the neck. Visual symptoms and headache are also common (17). Hydrocephalus due to impaired resorption of CSF in more advanced cases can be seen, progressing in extreme instances to a state of dementia, parkinsonism, seizure, or movement disorders which can be reversible with treatment of the vascular lesion (18,19,20,21,22). Patients with symptomatic DAVMs are reported to have a recurrence rate of hemorrhage or non-hemorrhagic complications of at least 15% to 19% per year, necessitating urgent treatment (23,24). Thus, the presence of cortical reflux of venous flow has been represented as an angiographic

indicator for urgent intervention, but it is likely that such a sense of urgency is not always valid. DAVMs with cortical reflux which are asymptomatic at the time of detection have a much lower rate of complication, <2% (25,26), implying that a more tempered approach should be advocated in advising asymptomatic patients for whom an endovascular treatment may involve significant risk.

indicator for urgent intervention, but it is likely that such a sense of urgency is not always valid. DAVMs with cortical reflux which are asymptomatic at the time of detection have a much lower rate of complication, <2% (25,26), implying that a more tempered approach should be advocated in advising asymptomatic patients for whom an endovascular treatment may involve significant risk.

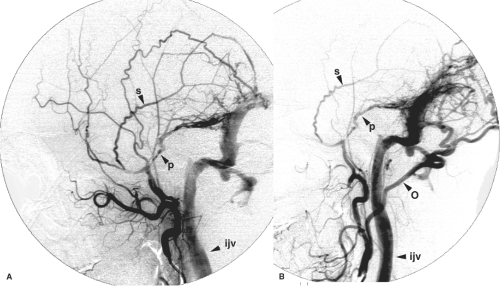

Dural arteriovenous fistulas are most commonly seen in the cavernous, sigmoid, and transverse sinuses (Figs. 20-6–20-10). Dural arteriovenous fistulas in the early stages may undergo spontaneous remission, although the likelihood of this in a well-established lesion is low (14,27,28). The dural sinus in early or uncomplicated cases may be completely normal in appearance or may show evidence of only partial thrombosis at the time of presentation. Depending on the patient’s tolerance of symptoms, expectant management of patients with uncomplicated DAVMs may be reasonable (Fig. 20-11). Training the patient to perform manual contralateral carotid compression at home has been advocated to eliminate smaller lesions over a few weeks, but the efficacy of this home remedy is dubious.

The venous pattern changes as the pressure in the venous system increases due to intimal flow-related changes in the main venous channels or recruitment of arterial feeders. Diversion of flow away from the involved sinus is seen angiographically with retrograde flow in the dural sinuses. It can be difficult to identify the presence of incipient cortical venous hypertension unless a careful examination of the entire angiogram is performed. For example, an internal carotid arteriogram in which opacification of the DAVM is not seen may still demonstrate very ominous signs in the patterns of flow in the venous stages.

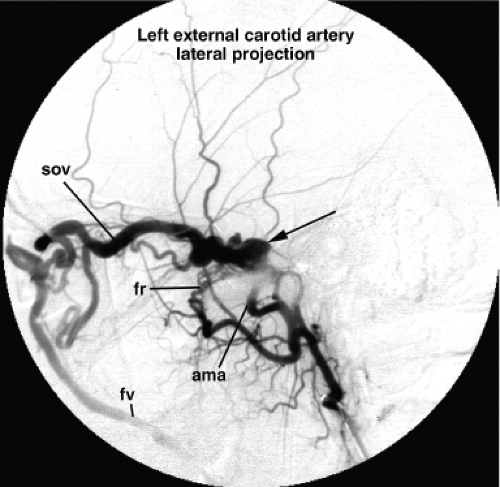

Figure 20-6. DAVM of the cavernous sinus. A lateral view of a left internal maxillary artery injection demonstrates opacification of a distended and tense cavernous sinus (arrow) via the accessory meningeal artery (ama) and artery of the foramen rotundum (fr ). The cavernous sinus drains anteriorly to the SOV and subsequently to the facial vein (fv ). In contrast to the patient in Figure 20-4, the IPS is not seen in this patient, which implies that transvenous access to the lesion through that route may not be possible. In a patient with a lesion such as this, urgency of treatment is guided primarily by concerns for the patient’s vision. An ophthalmologist’s involvement to monitor the intraocular pressure and visual acuity is imperative. The likelihood of such complications depends in part on the anastomoses of the ophthalmic veins with other drainage routes. |

With increasing venous and sinus hypertension, retrograde flow of contrast from the sinuses into leptomeningeal (cortical) veins becomes evident. With elevation of venous pressure in the cortical veins, new symptoms related to seizure, headache, venous hemorrhage, elevated intracranial pressure, and focal neurologic deficits can emerge. Depending on the venous territory involved, patients may present with focal hemispheric symptoms, motor weakness, and brainstem or cerebellar symptoms. Cranial nerve deficits may also be seen, particularly ophthalmoplegia in the setting of a cavernous sinus DAVM. Interestingly, it is during this stage of diversion of flow away from the sinuses into cortical veins, perhaps with progressive occlusion of the main sinus, that patients may experience a subjective improvement in tinnitus. Thus, such a report from a patient with a known DAVM is a concern, as it may bode an ominous turn of events. Immediate treatment is indicated when complications appear imminent. Urgent treatment is required also for patients with DAVMs near the cavernous sinus who are developing complications of exophthalmos, secondary glaucoma, or visual deterioration.

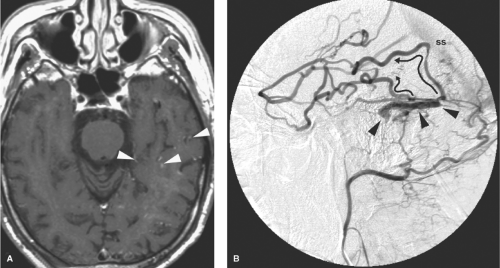

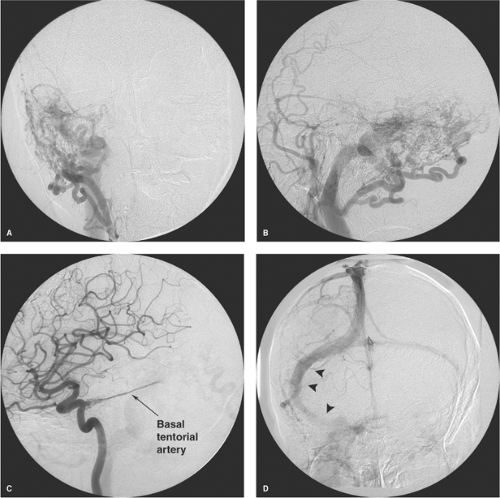

The gravest progression of the disease occurs when venous outflow is completely restricted to cortical veins due to complete occlusion of the sinuses. In these instances, the arterial flow may be directed exclusively into the subarachnoid veins or into an isolated segment of sinus that drains only through

cortical veins. These patients present with severe neurologic deficits, extensive cortical venous hypertension (Fig. 20-12), venous hemorrhages or infarcts, and hydrocephalus. DAVMs of the anterior cranial fossa or of the tentorium represent a particular risk of sudden massive frontal lobe or subarachnoid hemorrhage, which may be the presenting symptom in more than 70% to 80% of cases (Fig. 20-13) (29,30,31,32,33). DAVMs in the anterior cranial fossa are usually close to the cribriform plate and have a propensity to develop venous aneurysms or varices adjacent to the site of fistulous flow from the ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic arteries (34,35). Prompt surgical clipping of the DAVM is the treatment of choice for this particular subgroup of patients. Embolization usually is not favored for lesions in this location, given the risks and difficulties involved in catheterization and embolization of ophthalmic artery branches.

cortical veins. These patients present with severe neurologic deficits, extensive cortical venous hypertension (Fig. 20-12), venous hemorrhages or infarcts, and hydrocephalus. DAVMs of the anterior cranial fossa or of the tentorium represent a particular risk of sudden massive frontal lobe or subarachnoid hemorrhage, which may be the presenting symptom in more than 70% to 80% of cases (Fig. 20-13) (29,30,31,32,33). DAVMs in the anterior cranial fossa are usually close to the cribriform plate and have a propensity to develop venous aneurysms or varices adjacent to the site of fistulous flow from the ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic arteries (34,35). Prompt surgical clipping of the DAVM is the treatment of choice for this particular subgroup of patients. Embolization usually is not favored for lesions in this location, given the risks and difficulties involved in catheterization and embolization of ophthalmic artery branches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree