13 Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), or thrombosis of the intracranial veins and sinuses, is a rare disease with a variety of causes that accounts for 1% of all strokes. CVST is slightly more common in women due to pregnancy, the puerperium, and oral contraceptive use. Diagnosis is still frequently overlooked or delayed as a result of the wide spectrum of clinical symptoms and the often subacute onset. Because of its myriad causes and presentations, CVST is a disease that may be encountered by a wide variety of clinicians and specialties. Heparin is the treatment of choice. The prognosis is usually good, but adverse outcomes occur unpredictably and may lead to serious sequelae such as hemorrhage, brain herniation, or even death if not recognized and treated early. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a rare type of cerebrovascular disease recognized as early as 150 years ago.1 Initial descriptions focused on CVST as an infectious disorder that commonly affected the superior sagittal sinus and resulted in bilateral or alternating focal deficits, seizures, and coma, often leading to death. CVST was commonly diagnosed almost exclusively at autopsy and therefore considered to always be lethal.2 In early angiographic series, mortality still ranged between 30% and 50%, but in several recent series using modern imaging techniques a more benign condition has emerged, with a mortality of less than 10%. Over the past 25 years, CVST has been diagnosed much more frequently due to greater awareness and the availability of advanced neuroimaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1,3 The venous territories of the brain are less well defined than the arterial territories due to the presence of extensive anastomoses between cortical veins. These allow the development of collateral circulation in the event of a venous occlusion. The main cerebral venous sinuses affected by CVST are the superior sagittal sinus (72%) and the lateral sinuses (70%). In about one third of cases more than one sinus is affected. In 30 to 40% of cases both sinuses and cerebral or cerebellar veins are involved.3 The exact incidence in adults is unknown but is certainly much higher than previously thought based on autopsy series. The incidence rate may be as high as 30 to 40 cases per million adults.4 A Canadian study reported an incidence of 0.67 cases per 100,000 children younger than 18 years old; 43% of the cases reported in children were in neonates. The peak incidence in adults is in the third decade, with a male/female ratio of 3:10. This imbalance may be due to increased risk of CVST associated with pregnancy, the puerperium, and oral contraceptives/hormone therapies. This female preponderance is found in young adults but not in children or in older adults.5,6 In the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT) cohort, 75% of cases were women. Women were also significantly younger than men (mean 34 years versus 42 years) and had a better prognosis. A gender-specific risk factor, such as oral contraceptives, pregnancy, the puerperium, and hormone replacement therapy, was identified in 65% of women.6 Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a serious but potentially treatable disease that predominantly affects young adults, unlike arterial stroke, which is much more commonly with advancing age. Traditionally, CVST is divided into two groups: septic and aseptic. Currently there are more aseptic cases.7 This disease has been described as a continuing process in which the balance of prothrombotic and thrombolytic process is disturbed, leading to progressive extension of venous thrombosis over time.3 Several disorders can cause, or predispose patients to, CVST. There are currently more than 100 putative causes and risk factors associated with venous sinus thrombosis. Frequently, more than one cause will be found in an individual patient. The etiology is not identified in ~ 15 to 35% of cases even after extensive diagnostic investigations.2,8 In children, a risk factor was identified in 98% of all cases.3,9 Table 13.1 summarizes the most frequent causes. Much like deep venous thrombosis, the cerebral venous thrombus begins as a fibrin-rich red thrombus that progressively transforms into fibrous tissue if recanalization does not occur. Thrombosis of the venous structures causes an increase in venous pressure through a delay in venous emptying, decreased capillary perfusion pressure, and increased cerebral blood volume. The effect of the thrombosis on cerebral tissue depends on the availability of collateral venous channels and on the propagation of the thrombus. If there is sufficient venous drainage from collaterals, then only symptoms of headache or those related to intracranial hypertension appear. If venous drainage is insufficient, then the increase in venous and capillary pressure leads to blood–brain barrier disruption, resulting in vasogenic edema as leakage of blood plasma into the interstitial space.5,7 A CVST patient can present with no cerebral lesion on imaging or can show evidence of vasogenic edema. Pallor and edema of the cortex and of the adjacent white matter characterize cerebral infarcts macroscopically in the territory drained by a thrombosed vein. In addition, there are multiple petechial hemorrhages that may become confluent, especially in the white matter. These venous infarcts differ significantly from arterial infarcts in having more edema and less necrosis, explaining a much higher potential for recovery.5 Recently in an animal model of CVST, after inserting a solid graft into the superior sagittal sinus one study showed that apoptosis plays a crucial role during the development of CVST.10 In the more malignant scenario, unilateral or bilateral hemorrhagic lesions called hemorrhagic venous infarcts occur. Table 13.1 Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Causes and Risk Factors1,5,7,10

Cranial Venous Sinus Thrombosis Diagnosis and Management

History and Definitions

Epidemiology

Etiology

Pathology

Prothrombotic conditions | Antithrombin III deficiency |

Drugs | Oral contraceptives |

Malignancy | Visceral carcinomas, lymphomas, leukemia, myeloproliferative disease |

Infection | Mastoiditis, sinusitis, facial cellulitis, osteomyelitis, tonsillitis, abscess, empyema, meningitis |

Inflammatory diseases | Behçet’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, temporal arteritis, ulcerative colitis/Crohn’s disease |

Head injury and mechanical precipitants | Head trauma |

Note: Major causes and risk factors are in boldface.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is still frequently overlooked or delayed because of the wide spectrum of clinical symptoms, and subacute presentation or headache-only onset.9 Most patients present with symptoms that evolved over days or weeks. This variability of clinical features depends on several factors, such as the site and extent of the thrombosis, the rate of propagation of the occlusion, the age of the patient, and the nature of the underlying disease.5

Headache is the most common symptom of CVST and occurs in almost 90% of all cases.1–5 It is also the most common inaugural symptom, present in 70 to 75% of patients before the onset of other neurologic manifestations. The headache of CVST has no specific features. Its duration is usually a few days, but it may arise suddenly and be severe, mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage or thunderclap headache. The possibility of isolated headache as the only symptom of CVST has recently been emphasized. The diagnosis of CVST is particularly difficult in such patients, particularly if the results from computed tomography (CT) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing are normal.2,5,6 The frequency of various signs and symptoms of CVST are summarized in Table 13.2.

Table 13.2 Signs and Symptoms of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Presentation | % |

Headache | 80–98 |

Papilledema | 27–80 |

Seizures | 10–61 |

Motor or sensory deficits | 34–37 |

Mental status change | 10–64 |

Dysphasia | 12 |

Cranial nerve palsies | 12 |

Cerebellar incoordination | 3 |

Bilateral or alternating cortical signs | 3 |

Nystagmus | 2 |

Hearing loss | 2 |

Note: Patients may have multiple presentations

Source: Adapted from Guenther and Arauz7 and Poon et al.11

Focal or generalized seizures are more frequently seen in CVST (35–50%) than in arterial stroke. A very high incidence of seizures (76%) is seen in peripartum CVST.8

Focal neurologic signs are the most common finding in CVST (40–60% of all cases). Focal deficits in combination with headache, seizures, or an altered consciousness should raise suspicion for CVST as the diagnosis.6

Stupor or coma is found in 15 to 19% of patients at hospital admission and is usually seen in cases with extensive multi-sinus thrombosis or deep venous system involvement causing bilateral thalamic edema. Of all clinical signs reported in CVST, coma at admission is the strongest predictor of poor outcome.3,6

According to Bousser and Ferro,2 four main patterns have been identified:

1. Isolated intracranial hypertension: This pattern is associated with headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema, transient visual obscurations, and eventually sixth nerve palsies. This is the most homogeneous pattern of clinical presentation, accounting for 20 to 40% of CVST cases.

2. Focal deficits or partial seizures: This “focal” pattern, if accompanied by headaches or altered consciousness, should immediately arouse suspicion for CVST.

3. Subacute diffuse encephalopathy: This pattern is characterized by a decreased level of consciousness and sometimes seizures without clearly localizing signs. Such cases can mimic encephalitis or metabolic disorders.

4. Painful ophthalmoplegia: This pattern is caused by lesions of the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerves with additional features of chemosis and proptosis, suggesting cavernous sinus thrombosis. Often because of the masking effect of an inadequate antibiotic regimen, cavernous sinus thrombosis can take a more indolent form with an isolated sixth nerve palsy, mild chemosis, and proptosis.2–5

Many other unusual presentations have been described: transient ischemic attacks, attacks of migraine with aura, isolated psychiatric disturbances, tinnitus, isolated or multiple cranial nerve involvement, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.2

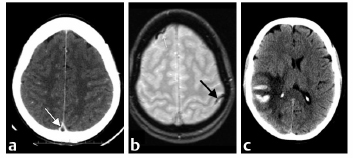

Neuroimaging

Given the diverse clinical presentations, appropriate neuroimaging investigations should be performed whenever CVST is suspected.1 The key to the diagnosis is the imaging of the venous system itself, which may show the occluded vessel or the intravascular thrombus.2 Unenhanced CT remains the technique of choice for screening patients with nonspecific clinical presentation and a low suspicion of CVST. Contrast-enhanced CT provides a more accurate diagnosis of CVST. MRI and magnetic resonance (MR) venography have been the noninvasive imaging technique of choice and are often used as the initial diagnostic test for suspicious cases. CT venography is now emerging as a convenient tool for emergency diagnosis, given its widespread accessibility at all hours.11

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree