OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Describe building a therapeutic alliance, eliciting the patient’s narrative, and assessing the patient’s vulnerabilities and strengths.

Explore the four critical components of therapeutic alliance: shared values and humanity, empathy, trust, and collaboration.

Describe the relevance of the therapeutic alliance to the effective care of vulnerable patients.

List the benefits of eliciting the patient’s narrative.

Review common psychosocial vulnerabilities and illustrate how identifying them can help create a patient-centered clinical encounter.

INTRODUCTION

Ms. Sviridov is a 67-year-old woman with chronic arthritis pain, hypertension, prior stroke, diastolic dysfunction, and diabetes. Despite a sizable, guideline-based medication regimen and frequent visits to both a primary care physician and a cardiologist, she has recalcitrant heart failure, requiring multiple hospital admissions. An extensive cardiac workup has been unrevealing. Ms. Sviridov is unhappy with her care and seeks out another primary care physician.

Vulnerable patients experience a triple jeopardy when it comes to health care: they are more likely to be ill; more likely to have difficulty accessing care, and when they do, the care they receive is more likely to be suboptimal. Often the suboptimal care reflects a mismatch between the psychosocial vulnerabilities that they bring to the clinical encounter and the knowledge, resources, attitudes, skills, and beliefs of the clinicians caring for them.1

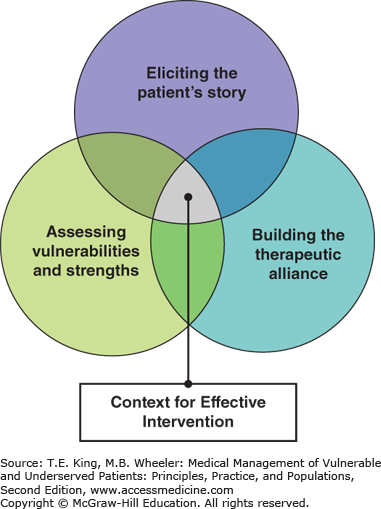

In this chapter, we focus on the centrality of building and sustaining strong clinician–patient relationships to improve the health of our patients. Three essential strategies are recommended to promote a context for effective care for vulnerable patients: (1) building a therapeutic alliance, (2) eliciting the patient’s story or “narrative,” and (3) assessing for the patient’s psychosocial vulnerabilities and strengths (or resilience factors). Clinicians can apply a combination of these approaches to create and sustain more productive and effective interactions and relationships with vulnerable patients (Figure 10-1).

VULNERABILITY AND THERAPEUTIC ALLIANCE

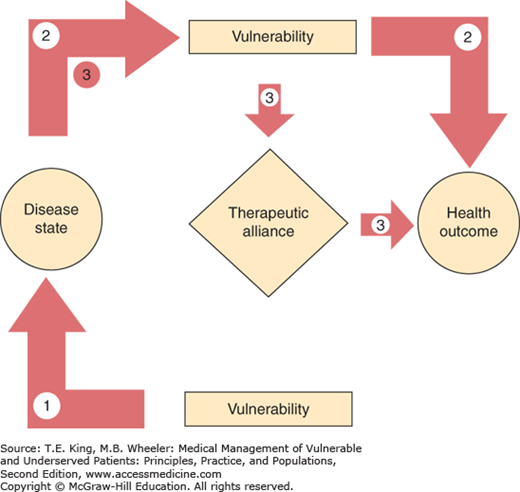

Psychosocial vulnerabilities can affect health and health care, either alone or in concert with the patient’s management of the disease (see Figure 10-2). The first path is a direct one, a situation in which the vulnerability in and of itself leads to poor health. Concrete examples of this mechanism might be the intravenous drug abuse and skin abscesses or intimate partner violence and head trauma. A second path is an indirect one (effect modification), whereby the vulnerability attenuates or impedes the benefits of medical treatment on coexisting medical conditions, for example, the vulnerability presents a barrier to optimal acute, chronic, and/or preventive care, thereby adversely influencing the disease course. Examples of this include the negative effects of depression on adherence to medications among patients with heart disease; inability to pay for medications and poor hypertension control, or food insecurity and poor diabetes control. The third mechanism, also an indirect one, is mediated entirely through the therapeutic alliance. In this path, the vulnerability affects components of the clinician–patient relationship or the therapeutic alliance (jeopardizing open disclosure, mutual trust, caring, and engagement), thereby limiting the benefits of a collaborative relationship on care. Examples of this include a patient with an undisclosed illness that is inconsistent with a prescribed treatment plan; a clinician whose belief systems regarding addiction impedes true engagement with a patient with a substance use disorder; or a patient with depression that impedes follow-through with prescribed treatment plan, thereby leading to mutual frustration and blame.2

Figure 10-2.

Multiple pathways by which social vulnerability affects health outcomes. In Path 1, the social vulnerability is directly linked to a disease (e.g., causal path). In Path 2, a social vulnerability impedes the patient’s management of her disease, thereby leading to worse health outcomes (e.g., effect modification). In Path 3 (e.g., indirect path), a social vulnerability impairs the therapeutic alliance between a provider and patient, thereby interfering with multiple aspects of the care process necessary for the management of the disease state (diagnosis, trust, disclosure, adherence, etc.), leading to worse health outcomes.

The term “therapeutic alliance” derives from a combination of the Greek word therapeuein (to serve) and the Latin word alligare (to bind) and was initially developed in the field of psychotherapy to describe a trusting, respectful, collaborative, and caring relationship between therapist and patient. Studies demonstrated that, regardless of the theoretical model of therapy, the presence of a therapeutic alliance was associated with positive treatment outcomes.3

In the field of medicine, a therapeutic alliance exists when patient and clinician develop mutual trusting, caring, and respectful bonds that allow collaboration in care and treatment.4,5,6 “Relationship-centered” care models build on the notion of the therapeutic alliance, and research reveals that patients reporting greater trust, increased satisfaction, shared values, and more collaborative relationships with clinicians have increased adherence to medication and treatment regimens and better health outcomes.7,8,9

Trust— Mutuality, particularly in trust, is crucial. Patients need to trust in their clinicians’ integrity and competence as healers. Clinicians need to trust that patients enter the relationship trying to do their best.

Empathy— Empathy too is necessary to form a strong therapeutic alliance. Demonstrating empathy, or recognizing and understanding the beliefs and emotions of another without injecting one’s own, allows the clinician to connect emotionally with the patient without pity or over identification, enriching the encounter for both. Feeling understood, particularly by your medical provider, can be profoundly comforting. Providing comfort is a reward in itself. Understanding a patient also imbues a clinician’s efforts, even the mundane filling out forms, with meaning.

Respect— Expressing respect for patients and treating them with dignity are important to creating therapeutic bonds. Respect requires a willingness to take the time to understand and explain, creating a context in which communication can occur as equals.

Agreement and collaboration— Clinicians and patients both need to feel comfortable articulating and agreeing on the goals of treatment. An honest dialogue may naturally lead to disagreement about these goals or how best to achieve them. Collaboration requires a meaningful partnership in which clinician and patient perceive that they are working together toward a common goal and committed to resolving inevitable conflict. It is often helpful to explore, identify, and affirm shared values in the nonhealth domains of life so as to forge an environment of collaboration for health decisions and behaviors (i.e., values affirmation exercises).10

Broadening the alliance— Initially, the fields of psychotherapy and health care envisioned the therapeutic alliance as a one-to-one relationship between clinician and patient. With the influence of systems theory, this alliance has broadened to include other important people involved in the care (e.g., family, consulting clinicians).11,12 Recent work by Wagner and others13,14,15 has further highlighted the important role that health systems play in either fostering or eroding the therapeutic alliance based on the policies they promote.

A growing body of evidence suggests that it is precisely with vulnerable patients that the therapeutic alliance can be most challenging, on the one hand, yet have its most profound benefits, on the other hand. In the therapeutic alliance, clinicians offer a professional relationship aimed at helping patients feel comfortable to be as open and honest as is necessary to receive the best care. Because of their privileged position, clinicians are permitted access to the interior of patients’ lives that few others are allowed. Consequently, they can build an alliance that empowers patients, reduces barriers to their care, and helps them find their inner strength.

Empowerment— Vulnerable patients often experience human relationships that are broken or disrupted (e.g., due to violence, immigration, mental illness, poverty, stigma, homelessness, illness). Through the therapeutic alliance, clinicians can offer a reliable, dependable, and continuous presence that is supportive, accepting, and nonjudgmental. They can provide safety, thus allowing patients to tell the stories of their lives and illness and disclose their vulnerabilities. By examining the patients’ strengths and resources, clinicians can provide a sense of dignity and hope. Through validating patients’ experiences, clinicians can help patients feel less marginalized. In supporting patients as competent and strong, clinicians can help them become actively involved in their care, increasing their agency.

Access to care and related resources— Vulnerable patients often face limited access to health care and social services. In part, they are often unaware of what is available and may not have the facility to negotiate complex, bureaucratic systems. Clinicians are in a position to remedy both of these barriers.

Through the therapeutic alliance, clinicians can help patients feel safe enough to reveal concerns or problems beyond the presenting problem, which they might not otherwise have done. For example, a patient seeking care for their diabetes may disclose that they live with an abusive partner, drink alcohol regularly, are food insecure, or are only sporadically housed. The clinician has the ability both to collaborate on treatment plans as well as facilitate entry into the various health and social systems that can address those vulnerabilities. The therapeutic alliance can help patients feel assured that clinicians will not abuse the disclosure of information (e.g., leading to rejection, stigmatization, or legal action) but will help them access resources critical for their health.

The absence of a therapeutic alliance can result in serious consequences for the health of vulnerable patients.

Mistrust— Clinicians often enter into relationships with patients assuming they share the same goals and will trust each other to do their best to attain them. However, many patients enter into the relationship with degrees of mistrust. This may result from their personal experiences with institutions in which they have felt betrayed or unwelcome, or be rooted in broader, historical experiences of their community. Clinicians should not automatically assume that they have patients’ immediate, total trust; rather, they often must earn it by demonstrating trustworthiness.

Poor care— Poor and minority patients frequently receive care in teaching hospitals and community health centers where the turnover of providers can be high. Patients may question clinicians’ motivation and commitment, fearing that they are educational fodder for trainees who will go on to care for the more privileged. When clinicians do not offer certain treatments, they may be suspicious about the clinicians’ willingness to expend resources for them. When clinicians persuasively argue for unwanted treatments, they may fear being used as experimental “guinea pigs.” Rather than raising concerns or disagreements with a clinician whose motives they question, they may choose not to follow through on recommended treatment or simply not return for care.

Disrespect— Perceived disrespect and discrimination due to race or socioeconomic status has been associated with lower satisfaction with the health-care system and worse health outcomes among patients with chronic illness.16,17 Studies found that significant proportions of Blacks, Latinos, and Asians and those with lower educational attainment reported that they were treated with disrespect, were treated unfairly, or received worse care because of their position in society. These perceptions influenced whether patients followed recommended advice or delayed needed care for chronic illness. Communicating respect is essential to demonstrating to vulnerable patients that clinicians are willing to enter into a relationship based on equality and dignity.

Poor collaboration— In the absence of a trusting relationship, true collaboration may be difficult to achieve. Fear of being punished or treated unfairly for speaking truthfully can lead patients to withhold their beliefs and values about a suggested treatment plan, or be unwilling to follow through on a recommendation. Clinicians, in turn, can feel frustrated and mistrustful when they wonder if they are being misled or if their patients really care about their health.

Shared decision making is often promoted as a model for mutual agreement and collaboration. However, research with diverse populations suggests that clinicians and patients apparently engaging in the cardinal behaviors of shared decision making, may still not perceive that a collaborative partnership exists between them.2 Indeed, being treated with respect and dignity may be more important than engaging in shared decision making, and lead to positive outcomes (i.e., higher satisfaction, adherence, and receipt of optimal preventive care).18

BUILDING A THERAPEUTIC ALLIANCE WITH VULNERABLE PATIENTS

No simple, protocol-like statements or behaviors can make another person feel cared for or respected. However, if we consciously strive to transmit a sense of trust, caring, and respect along with a desire to enter into true partnership, we increase the likelihood of forming productive relationships with patients. Some guidelines to consider in this process include the following:

Health-care workers need to state clearly their desire to be available to their patients within the scope of their practice (e.g., “I will be your regular doctor. Here is my telephone number with a voice mail; I check it three times a week and will get back to you as soon as possible.”); define realistic expectations for what we can do between visits (e.g., “I will check into support groups and tell you at our next appointment.”); and follow through on what we have promised.

The humanity of the health-care worker and the patient should be expressed and elicited. This may include the sharing of beliefs, values, and feelings as they relate to the clinical issues facing them (e.g., express concern about suffering, “I am sorry you have to deal with this pain”; self-disclosure to identify a shared history or common interests with the patient; “As a parent, I can’t imagine how incredibly strong you had to be to escape with your children.”). It may also include maintaining a humanistic approach in one’s personal attitude and communication techniques in domains beyond health. The mnemonic “CAPTURES” (Box 10-1) is a very useful tool to ensure that humanism suffuses the clinical encounter and clinician–patient relationship. It has particular salience in bridging the gap for more “difficult patients.”19

BOX 10-1. Personal Attitudes and Techniques to Enhance a Sincere Humanistic Component in the Encounter (mnemonic: “CAPTURES*”)