OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define the patient-centered medical home.

Review the rationale for the medical home model and a high-performing primary care delivery system.

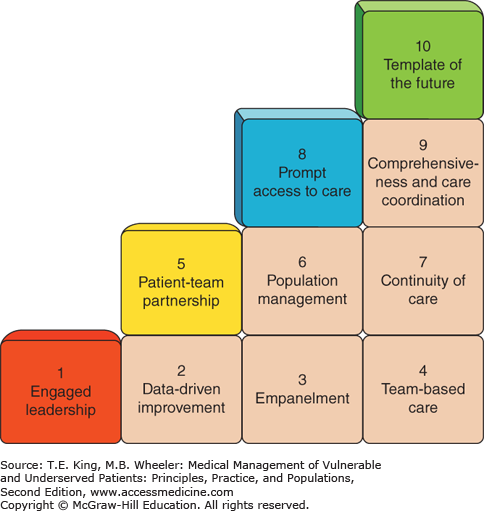

Describe the 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care.

Discuss the challenges and opportunities of creating medical homes in safety-net settings.

Mrs. C is a 58-year-old Spanish-speaking woman with poorly controlled diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. She works as a housekeeper and frequently has to miss visits with her primary care provider (PCP) because of work. Mrs. C’s PCP has a panel of 2000 patients, sees 30 patients per day, and does not speak Spanish. During her routine 15-minute visits, her PCP explores Mrs. C’s symptoms of back pain and depression using her daughter as an ad hoc interpreter, reviews her HbA1c of 9.5 and blood pressure of 160/100, and recommends dose adjustments to her medications. The PCP feels that there is not enough time to explain illnesses and treatments to Mrs. C. and worries that they do not get to preventive care. At the end of a visit, both Mrs. C and the PCP are often dissatisfied with the encounter. Despite the PCP’s best intentions and hard work, Mrs. C’s chronic conditions do not improve.

INTRODUCTION

Primary care in the United States is at a crossroads. With skyrocketing costs, fragmented care, limited access, and the primary care physician shortage, primary care needs to undergo substantial transformation. The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is widely advocated as a model to address the challenges of primary care and achieve what the Institute for Healthcare Improvement calls the “triple aim”—better population health, improved patient experience, and reduced per capita costs.1

The PCMH model aims for “comprehensive, continuous, patient-centered, team-based, and accessible primary care delivered in the context of a patient’s family and community.”2 The model first originated from the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1967 and was endorsed by the four main primary care professional societies in the 2007 “Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.”3,4 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) calls for implementation of the medical home, and multiple public and private groups have supported widespread medical home demonstration projects.5,6,7 With these efforts, the number of practices undergoing medical home transformation nationwide has grown rapidly.

The medical home model is especially important in safety-net settings that provide primary care to underserved communities. Vulnerable populations face substantial barriers to care including limited access, low English proficiency, low health literacy, psychosocial complexity, and multiple medical comorbidities. Given its emphasis on access, whole-person orientation, team-based care, and care coordination, the PCMH model has the potential to address the many concerns of vulnerable populations.8

Providing patients with insurance coverage and a medical home has been found to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in access and quality of preventive and chronic care and to improve outcomes for vulnerable patient populations.9 Safety-net clinics, however, face additional challenges to the transformation required to adopt the PCMH model. They frequently have unstable sources of funding, limited resources, high staff turnover, and heavy patient demand.10,11 Policies and payment reform that promote medical home transformation in safety-net settings could help reduce disparities among underserved communities.

This chapter discusses the background of the medical home and presents a framework for creating the medical home—the 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care.12 We will highlight the salient aspects of medical home implementation in safety-net settings serving vulnerable populations.

WHAT IS PRIMARY CARE?

Primary care is “the provision of integrated, accessible health-care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health-care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.13 Barbara Starfield, a foremost authority on primary care, describes four pillars of primary care practice: first-contact care, continuity over time, comprehensiveness, and coordination with other parts of the health system (Box 11-1).14

Box 11-1. Four Pillars of Primary Care Practice

| Pillars | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| First-contact care | Single door through which patients can enter the health-care system |

| Continuity over time | Patients and families have a regular source of care over a significant period |

| Comprehensiveness | Whole-person orientation, addresses primary care’s responsibility to deliver all types of health services—preventive, acute, chronic, palliative, supportive |

| Coordination | Refers to the integration of a patient’s care no matter where or by whom the care is obtained |

A health system based on the principles of primary care is likely to have better quality, improved patient experience, and reduced costs—the triple aim.15 Primary care is more likely to provide recommended preventive services16 and patients are more likely to be satisfied with their care.17 Nations with a larger ratio of primary care physicians to specialists tend to have lower per capita health expenditures.18 Similarly, a study from 2004 showed that states in the United States with more generalists have higher quality of care and lower per capita Medicare expenditures, while states with more specialists per capita have the reverse.19

While primary care is essential as the foundation of any health-care system, primary care in the United States has serious shortcomings. While half of physicians in most nations practice primary care, only one-third of US physicians practice primary care, creating a chronic primary care shortage. Primary care is unevenly distributed across the United States. The ratio of primary care physicians to population is half in rural areas compared with urban areas; similar disparities exist for economically disadvantaged urban areas. A total of 65 million people in the United States (about 20%) live in areas designated as primary care health professional shortage areas. These communities have high proportions of uninsured, poor, and minority populations with higher death and disease rates than in communities with better access to primary care. From 1998 to 2006, the number of counties with medically disenfranchised populations increased by 52%.20

In 2013, 52% of Americans reported being unable to get a same-day or next-day appointment when they were sick; 26% waited 6 days or more for an appointment. Only 35% of primary care practices offer after-hours care. Forty-eight percent of Americans used an emergency department in the past 2 years, often because they were unable to gain access to primary care.21 Access to care is particularly difficult for patients who are uninsured or insured through Medicaid. In 2011, 31% of physicians would not accept any new Medicaid patients. Thus, uninsured patients are left to seek care in stressed county-run health systems or community clinics that often lack the capacity to care for all the patients needing assistance.22

Even when patients can access primary care, their visits are often rushed and their problems are not addressed. Fifty percent of patients leaving a physician visit report that they do not understand what the physician said.23 In an audiotaped study, patients making an initial statement of their problem were interrupted after an average of 23 seconds.24

Primary care practices are often hectic, concentrating much of the work in the hands of overly busy and often burned-out physicians. Nonphysician staff are not usually trained or empowered to contribute to the care of patients. Continuity of care can be poor, and the practice may not address the needs of the entire practice population. Care is often driven by urgent patient concerns, and chronic disease care may be neglected. In the words of the nation’s leading health-care champion Donald Berwick, “We are carrying the 19th-century clinical office into the 21st-century world. It’s time to retire it.”25

In 2007, the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, and American Osteopathic Association united around a vision for primary care—the joint principles of the PCMH, an elaboration of the four pillars of primary care articulated by Barbara Starfield in 1998.4,14 Propelling this effort was the willingness of some payers, including government, to consider enhanced payments to practices meeting certain qualifications.

In 2008 (modified in 2011 and 2014), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) unveiled a PCMH recognition process with specific requirements.26 Other US organizations have developed their own recognition programs. Primary care practices find PCMH standards useful for targeting their improvement efforts; however, the PCMH recognition process has come under criticism. Practices may receive recognition without transforming themselves in a fundamental way. Some feel the NCQA requirements overemphasize technology and that the checklist does not accurately capture needs of patients and practices.2 A study of 30 Los Angeles community health centers found no association between NCQA medical home scores and the quality of diabetes care.27 Recognition standards function more as an assessment tool to guide transformation rather than a representation that successful practice transformation has been achieved.

In 2012, the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Center for Excellence in Primary Care developed a conceptual model for fundamental primary care transformation, the 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care (Figure 11-1).12 The remainder of this chapter describes the building blocks, emphasizing their relevance to vulnerable populations.

Mrs. C switched to a community health center offering a PCMH model of care, and she was connected to a new PCP and care team. She was linked to a trained Latina medical assistant who provided health coaching and a nurse who saw her for planned chronic disease group visits, giving her the knowledge, skills, and confidence to better self-manage her diabetes, blood pressure, and back pain. An onsite behaviorist on her care team engaged Mrs. C for her depression. Mrs. C agreed to make concrete lifestyle changes and learned the proper instructions for taking her medications. Within 6 months, her HbA1c dropped to 7.2%, her blood pressure to 135/85, and her mood had improved.

THE 10 BUILDING BLOCKS

The building blocks were developed from observations of 23 high-performing primary care practices in the United States. While practice settings varied widely (small private offices, community health centers, and hospital-based or in large delivery systems), internally they looked surprisingly similar in their consistent implementation of 10 elements of primary care transformation (Figure 11-1).

Engaged leadership, including physicians, staff, and patients, create a practice-wide vision with concrete goals and objectives. High-performing practices have leaders who are fully engaged in the process of improvement and who learn how to facilitate organizational transformation. High-performing practices have leadership at each level of the organization. Medical assistants, receptionists, clinicians, and other staff are involved in leading efforts to improve workflows.

Many community clinics actively engage patients in the transformation process, as the majority of their boards are composed of consumers.28 Patients act as experts in the health-care experience to identify priorities for improvement. In clinics with high proportions of vulnerable populations, leaders need to prioritize services specific to vulnerable populations such as language-concordant staff, health coaching, on-site behavioral health staff, or low literacy education materials. Leaders create concrete, measurable goals and objectives, such as the percent of our patients with diabetes who have a HbA1c greater than 9 will drop from 20% to 10% by June 30, 2016.

Monitoring progress toward objectives requires the second building block: data systems that track metrics across the triple aim—clinical (e.g., cancer screening and diabetes management), operational (continuity of care and access), and patient experience and staff satisfaction metrics. In addition to traditional metrics, high-performing safety-net practices also measure data to identify disparities in care, and target improvement efforts to reduce these disparities. Performance measures are often communicated to each clinician and care team and regularly shared with the entire staff to stimulate and evaluate improvement. Data dashboards may be displayed in prominent locations within the practice and performance data are discussed in team meetings. For many safety-net systems, data-driven improvement will require replacing outdated technology with robust health information technology (HIT) systems with patient registry functions to measure and track outcomes.

Empanelment means linking each patient to a care team and a personal primary care clinician. Empanelment is the basis for the therapeutic relationship that is essential for good primary care.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree