Cultural differences care pathways, service use, and outcome

Jim van Os

Kwame McKenzie

This chapter discusses the influence of culture on the route an individual takes to access treatment for psychological distress and the treatment received. Culture is difficult to measure. All categories of cultural variables have different meanings and measure different things. Research into them leads to different hypotheses. Given this reality, there is no need to join the cul-de-sac argument of whether one or the other is the most important. In the discussion below, the roles of ethnicity and of socio-economic, political, community, national, and other factors that help to define the culture of an individual or a group are acknowledged. Associations with pathways to care, service use, and outcome will be presented.

Care pathways

Cultural variation in pathways through care

At the beginning of the pathway to care, the individual displays cognitive, physical, or behavioural changes. They or their family, friends, or wider community interpret these as in need of some remedy. The individual’s personal resources and then informal resources of family and friends are often triggered to help deal with the problem. These may lead to resolution but if they do not they may lead to presentation through an ever more distant and ‘professional’ array of caregivers, help agencies, and formal medical services. Most help for psychological problems is not given by mental health services. Interventions and their perceived success or failure move an individual along a pathway.

Pathways through care have differing directions and durations. These depend on where the pathway starts, the presenting symptoms, and psychosocial and cultural factors in the individual, their community, and the services used. Pathways are not random, they are structured and set by a dialogue between the individual, the community, and the code of the statutory services and the law set within that country.(1)

At each level the aim of care is to help the individual move down to less professional interventions until they are either back in the community or at the lowest intensity of care that meets their needs. Traditionally, care pathways have considered routes to getting treatment but with de-institutionalization, social inclusion and the recovery model, pathways out of care need to be considered more widely.

International comparisons

Cultural variation in pathways to care for a mental health problem is readily, though crudely, demonstrated through international comparisons. For example, in an international study of the pathways to care of 1554 patients newly referred to the mental health services in 11 centres in different countries, the majority of patients (63–80 per cent) were referred by their general practitioner in United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Czechoslovakia, Cuba, Mexico, and Aden Democratic Republic of Yemen. Only between 0–15 per cent of patients in these centres had referred themselves, with the exception of Mexico (24 per cent). In Kenya, only 7 per cent were referred by general practitioners but 72 per cent were referred by a hospital doctor. In Pakistan and India, a quarter of patients were referred by general practitioners, a quarter by hospital doctors, a third were self-referred, and 11–17 per cent were referred by religious healers. In Indonesia, both primary care and native healer referrals constituted each around a third of all referrals. The differences between these 11 centres largely reflected the people’s choice of first port of call for a psychiatric problem.(2)

International differences in pathways are also reflected in primary health care studies. In a 14 country World Health Organization (WHO) investigation, the proportion of attendees with anxiety and depression as defined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) varied five-fold across centers. Asian sites reported the lowest rates and European and South American sites the highest. The differences in prevalence may reflect a combination of demographic differences between attendees, true differences in population prevalence, the differential availability of other culture-specific pathways to care for the psychologically distressed, and differential sensitivity of the CIDI in picking up psychiatric disorder in different cultures.(3)

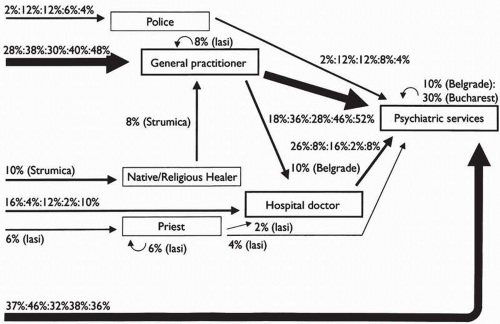

Geographically less dispersed countries also demonstrate significant differences in care pathways. In a recent study of 6 Eastern European countries, the percentage of new patients with schizophrenia who first sought care from psychiatric services ranged

from 69 per cent in Bucharest (Romania) to 47 per cent in Zagreb (Croatia). Thirteen percent of patients first sought care from general practitioners in Strumica, Macedonia but 47 per cent in Zagreb. The police were the first port of call in 8 per cent of cases in Bucharest but for none in Zagreb.(4)

from 69 per cent in Bucharest (Romania) to 47 per cent in Zagreb (Croatia). Thirteen percent of patients first sought care from general practitioners in Strumica, Macedonia but 47 per cent in Zagreb. The police were the first port of call in 8 per cent of cases in Bucharest but for none in Zagreb.(4)

This study used the ‘encounter form’ developed for the WHO which can be used to map and quantify pathways to care (Fig. 7.3.1).

Marked differences in pathways to care also exist within countries and groups. The increase in the use of involuntary admission of African-Caribbeans in the UK and African-Americans in the US is well documented. The reasons for this are unclear but some argue that it reflects service configuration.(5) More recently, increased involuntary admission rates have been reported in the Maori population of Auckland, New Zealand.(6)

Geographic and ecological factors may also contribute to variation in pathways to care within a country. In a Canadian province, involuntary admissions were shown to be related to the size of a community and its proximity to the hospital. Thus, involuntary admission rates were increased if a community was close to the hospital. Rates were also higher in both densely populated inner city areas as well as in cities of less than 500 people. The higher rates of involuntary admission in small towns may be related to a decreased likelihood of being tolerated or remaining anonymous.(7) Despite a similar mental health act, involuntary admissions in Greenland were found to be twice as high as they were in Denmark or the Faroe Islands. The excess risk was associated with the higher homicide rate, lower psychiatric bed availability, lower access to psychiatric care, small settlements, and increased alcohol consumption and violence in Greenland.(8)

Factors associated with cultural variation in pathways

How interpersonal or cultural factors are translated into differences in pathways has rarely been assessed. However, a number of factors have been identified that contribute to cross-national and cross-ethnic differences.

The family may play an important role. An American study reported that Chinese patients were kept for extended periods of time within their families at the beginning of pathways, while Anglo-Saxons and Central Europeans were referred by their relatives or themselves to a range of mental health and social agencies. Native Americans tended to be referred by people other than relatives or themselves.(9) In another study, both Asians and African-Americans showed more extended family involvement, and the involvement of key family members tended to be persistent and intensive in Asians. Ethnicity was also associated with the length of delay, Asians showing the longest delay and white people, the shortest.(10)

The history of and the way that institutions promote themselves can affect the attitude minority patients have to them and so their likelihood of using them. For example, the view of American hospital services by ethnic minority patients has been tarnished by the American Medical Association’s support for segregated wards until the 1960s.(11)

The experience of illness is a culturally shaped phenomenon. The monitoring of change, the understanding of symptoms, the language used to present symptoms, and the fears that accompany symptoms are all suffused with cultural interpretations.(12) Cultural differences in displaying distress are most obviously seen in culture-bound syndromes but are present in the content of delusions and somatic presentation of distress. Somatic symptoms are located in multiple systems of meaning that serve diverse psychological and social functions. In one study, the experience of neurotic patients in India was labeled depressive by clinicians using DSM-IIIR, whereas the patients emphasized their somatic experience.(13) Such discrepancies between professional theory and patients’ experience may have an impact on the recognition and treatment of psychiatric disorder. For example, ethnic difference between the doctor and the patient or linguistic/communication problems had previously been offered as reasons for British general practitioners missing depression in South Asian women. However, South Asian doctors are also more likely to miss

depression in South Asian women.(14) Thus, rather than ‘ethnic match’, the culture of medicine may be the important determinant of recognition of depression in this group and its treatment. Longer delays in first contact with a mental health professional,(10) reduce likelihood of successful drug treatment,(15) and poorer outcomes(16) have been reported in groups of Asian patients. The mismatch between patient experience and culture of medicine appears ubiquitous. In Turkey, psychiatric patients with somatic presentations were shown to have longer delays because they went to see hospital doctors first before being referred to a psychiatrist.(17) A study in Nigeria found that a large proportion of depressed patients initially received another diagnosis because of somatic presentation.(18) However, emphasis on somatic experience on the part of the patient does not preclude the patient’s recognition of psychological factors, and addressing culturally shaped experience of illness can help clinicians determine underlying aetiology and understand patients with challenging somatic symptoms.(19)

depression in South Asian women.(14) Thus, rather than ‘ethnic match’, the culture of medicine may be the important determinant of recognition of depression in this group and its treatment. Longer delays in first contact with a mental health professional,(10) reduce likelihood of successful drug treatment,(15) and poorer outcomes(16) have been reported in groups of Asian patients. The mismatch between patient experience and culture of medicine appears ubiquitous. In Turkey, psychiatric patients with somatic presentations were shown to have longer delays because they went to see hospital doctors first before being referred to a psychiatrist.(17) A study in Nigeria found that a large proportion of depressed patients initially received another diagnosis because of somatic presentation.(18) However, emphasis on somatic experience on the part of the patient does not preclude the patient’s recognition of psychological factors, and addressing culturally shaped experience of illness can help clinicians determine underlying aetiology and understand patients with challenging somatic symptoms.(19)

Beliefs about why the problem has arisen, shape the pathway into care. How important this is depends on how different a culture’s models of illness and treatment are from that of the service providers. For example, in a study of help-seeking behaviour of families of patients with schizophrenia in India, most of those who believed in supernatural causation consulted indigenous healers first and those who identified schizophrenia as a medical problem consulted practitioners of modern medicine.(20) Similarly, a study in Ghana found that a perceived supernatural cause of mental health problems was associated with a marked reduction in the likelihood of consulting a mental hospital facility.(21) Surveys among Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans show that(22,23) the association between help-seeking, service and acculturation is mediated, amongst others, by beliefs and explanatory models of psychiatric symptoms. Patient satisfaction is highest if the explanatory model of the patient is matched with that of the service provider.(24) Mental health-care professionals are also prone to differences in explanatory models. For example, a comparison between mental health-care professionals in Saudi Arabia and the UK revealed that the staff in the UK believed in a greater range of possible causes and diagnoses for auditory hallucinations than staff in Saudi Arabia. Differences in belief were associated with different expectations regarding efficacy of possible treatments.(25)

Pathways to care are shaped by public opinion and stigma. Such factors can also contribute to the resources that a society will give, and where and by whom treatment is given. A population survey in Germany showed that the lay public generally held psychotherapy in high esteem and the vast majority of respondents rejected pharmacotherapy for psychological problems. Psychoanalysis was the most popular approach in the western part of Germany but in eastern Germany the preference was for group therapy.(26)

Similarly, because psychiatric practice remains to a large degree opinion-based within Europe, differences exist between national samples of psychiatrists with regard to the diagnosis, aetiology, treatment, and outcome of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Cultural divergence is especially evident with regard to differential emphasis on psychodynamic and biological approaches,(27) and the level of availability of psychotherapy within the health service in European countries appears to be associated with the dominant therapeutic culture of psychiatrists.(28)

The quality of mental health legislation, and, perhaps more importantly, the degree to which correct implementation is enforced have an effect on care pathways. Increased stigma of psychotic illness and fear of public safety have led to compulsory treatment in the community becoming law in the UK. This could change pathways to and through care.(29) In the Netherlands, a weak and impractical act has been criticized for denying patients with severe mental illness the treatment they need. In Spain, to date no specific mental health act exists. In countries like the United Kingdom and France, involuntary admission is in practice, a largely clinical decision, and therefore more easily to put into effect compared with, for example, The Netherlands and most of Germany where the decision is ultimately made by the judiciary. In the United Kingdom and France, the police may bypass medical referral and take people behaving strangely in a public place directly to a psychiatric hospital. This has been shown to be an important pathway for certain ethnic minority groups, such as African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom.(30)

Filters on the pathway to care and service use

Filter permeability and service use

The majority of people in psychological distress never present to formal health services. If formal help is sought, the likelihood of receiving such help is influenced by the permeability of a number of filters (see Chapter 7.8). For example, once the decision to seek formal help is taken, actual receipt of help depends on the ability of the professional at the first port of call (usually primary care services) to recognize the presence of mental disorder. The permeability of subsequent filters determines the rate with which patients move from primary care service to specialist mental health outpatient services, and from specialist outpatient to hospital-based psychiatric services and back down the hierarchy.

(a) Cross-ethnic differences

There are important cross-ethnic and cross-national differences in the permeability of filters along the pathway to care. Recognition of symptoms by mental health professionals is an important factor. Recognition of distress is dependent on the way symptoms are elicited. For instance, the recognition by primary care doctors of psychiatric disorder in African-Caribbeans and South Asians in the United Kingdom has been shown to be poor.(31) There are a number of reasons for this including differences between the symptoms expected by doctors and those presented.(12) Despite the fact that they visit their general practitioner more often, women of South Asian origin with depression are less likely to be diagnosed and treated than white British women. Detection of depression depends on the doctor’s skill but also whether the patient tells the general practitioner about her worries. Those who believed that a doctor was the right person to deal with depression were found to be more likely to disclose information and more likely to be diagnosed and treated.(12) South Asian women are less likely than white British women to think that a doctor was the right person to deal with depression.(32) A one-year follow-up of the sample of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program revealed that African-Americans, Hispanics, and other minorities were much less likely to have consulted with a professional in the specialized mental health care sector than white people. The odds of consultation in African-Americans was less than one-quarter of that in white people even after adjustment for confounders.(33) Similarly,

African-American children and adolescents may also remain under-treated although they may have higher levels of symptomatology.(34) Differences between American ethnic groups are also apparent in populations with identical insurance coverage.(35) Hence, these findings(36) suggest low permeability of filters on the pathway to mental health care. Reasons for this may include that African-Americans are less inclined to seek professional help because of increased tolerance to depressive symptoms, but also because of fear of hospital admission.(37) In comparison to all other ethnic groups, African-Americans make more use of emergency rooms for routine psychiatric care.(38)

African-American children and adolescents may also remain under-treated although they may have higher levels of symptomatology.(34) Differences between American ethnic groups are also apparent in populations with identical insurance coverage.(35) Hence, these findings(36) suggest low permeability of filters on the pathway to mental health care. Reasons for this may include that African-Americans are less inclined to seek professional help because of increased tolerance to depressive symptoms, but also because of fear of hospital admission.(37) In comparison to all other ethnic groups, African-Americans make more use of emergency rooms for routine psychiatric care.(38)

Despite the low permeability of the filters on the pathway to care there is an over-representation of African-Caribbeans and African-Americans at the level of hospital-based psychiatric services. Possible mechanisms for this include failure of community services to engage mentally ill African-Caribbean men(39) and bypass of the usual filters by, for example, compulsory admission to hospital with or without police involvement.(40) It has been shown that police involvement and compulsory admission to hospital is strongly associated with the absence of general practitioner involvement.(41) Levels of perceived violence and rates of involuntary admission may be due to stereotyped attitudes of the police and mental health professionals or may be in part due to a higher rate of presentation of psychosis that is superimposed on intact premorbid personalities. It has been suggested that reactive forms of psychotic illness in African-Caribbeans are wrongly labelled as schizophrenia.(42) Higher functioning, less withdrawn patients may be perceived as constituting a higher risk by police and mental health professionals. Another factor is that, despite low rates of recognition by general practitioners, African-Caribbeans are most likely to be referred on to a specialist, followed by white people and then people from south Asia even when socioeconomic class and diagnosis are taken into account.(31)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree