Culture-Related Specific Psychiatric Syndromes

Wen-Shing Tseng

The concept of culture-related specific (psychiatric) syndromes

In certain ways, all psychiatric disorders are more or less influenced by cultural factors, in addition to biological and psychological factors, for their occurrence and manifestation. ‘Major’ psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders) are more determined by biological factors and relatively less by psychological and cultural factors, but ‘minor’ psychiatric disorders (such as anxiety disorders, conversion disorders, or adjustment disorders) are more subject to psychological causes as well as cultural factors. In addition to this, there are groups of psychiatric disorders that are heavily related to and influenced by cultural factors, and therefore addressed as culture-related specific psychiatric syndromes.

Culture-related specific psychiatric syndromes, also called culture-bound syndromes(1) or culture-specific disorders,(2) refer to mental conditions or psychiatric syndromes whose occurrence or manifestations are closely related to cultural factors and thus warrant understanding and management primarily from a cultural perspective. Because the presentation is usually unique, with special clinical manifestations, the disorder is called a culture-related specific psychiatric syndrome.(3) From a phenomenological point of view, such a condition is not easily categorized according to existing psychiatric classifications, which are based on clinical experiences of commonly observed psychiatric disorders in western societies, without adequate orientation towards less frequently encountered psychiatric conditions and diverse cultures worldwide.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, during a period of colonization by western societies, western ministers, physicians, and others visited faraway countries, where they encountered behaviours and unique psychiatric conditions that they had never experienced at home. Most of these conditions were known to the local people by folk names, such as latah, amok, koro, susto, and so on, and were described by westerners as exotic, rare, uncommon, extraordinary mental disorders, mental illnesses peculiar to certain cultures, or culture-bound syndromes. The latter term implies that such syndromes are bound to a particular cultural region.(4)

Recently, however, cultural psychiatrists have realized that such psychiatric manifestations are not necessarily confined to particular ethnic-cultural groups. For instance, epidemic occurrences of koro (penis-shrinking panic) occur among Thai or Indian people, not only among the Southern Chinese as originally claimed; and sporadic occurrences of amok attacks (mass, indiscriminate homicidal acts) are observed in the Philippines, Thailand, Papua New Guinea, and in epidemic proportions in many places in South Asia,(5) in addition to Malaysia where it was believed to most commonly occur. Terrifying examples of amok have recently occurred with frequency on school campuses and in workplaces in the United States.

Therefore, the term culture-bound does not seem to apply, and it has been suggested that culture-related specific psychiatric syndrome would be more accurate to describe a syndrome that is closely related to certain cultural traits or cultural features rather than bound specifically to any one cultural system or cultural region.(4) Accordingly, the definition has been modified to a collection of signs and symptoms that are restricted to a limited number of cultures, primarily by reason of certain of their psychosocial features,(6) even though it is recognized that every psychopathology is influenced by culture to a certain degree.

Subgrouping of culture-related specific syndromes

In order to organize and categorize the various culture-related syndromes, several different subgroup systems have been proposed by different scholars in the past, such as by cardinal symptoms or by ‘taxon’ (according to a common factor). However, instead of focusing on the clinical manifestation descriptively, it will be more meaningful to subgroup the syndromes according to how they might be affected by cultural factors.

It has been recognized that there are different ways culture contributes to psychopathology. Namely: pathogenetic effect (culture has causative effect), pathoselective effect (culture selects the nature and type of psychopathology), pathoplastic effect (culture contributes to the manifestation of psychopathology), pathoelaborating effect (culture elaborates and reinforces certain types of manifestations), pathofacilitating effect (culture contributes to the frequent occurrence of particular psychopathologies), or pathoreactive effect (culture determines the reaction to psychopathology). Furthermore, culture impacts differently on different types of psychopathology.

If the psychopathology is divided into that which is more biologically determined (such as organic mental disorders or major psychiatric disorders), psychologically determined (such as minor psychiatric disorders), or socio-culturally determined (such as culture-related specific syndromes or epidemic mental disorders), it can be said that a pathoreactive effect is observed for all types of psychiatric disorders while a psychogenetic effect is observed mainly for those psychiatric disorders which are more socio-culturally determined, such as culture-related specific syndromes or epidemic mental disorders.

If the psychopathology is divided into that which is more biologically determined (such as organic mental disorders or major psychiatric disorders), psychologically determined (such as minor psychiatric disorders), or socio-culturally determined (such as culture-related specific syndromes or epidemic mental disorders), it can be said that a pathoreactive effect is observed for all types of psychiatric disorders while a psychogenetic effect is observed mainly for those psychiatric disorders which are more socio-culturally determined, such as culture-related specific syndromes or epidemic mental disorders.

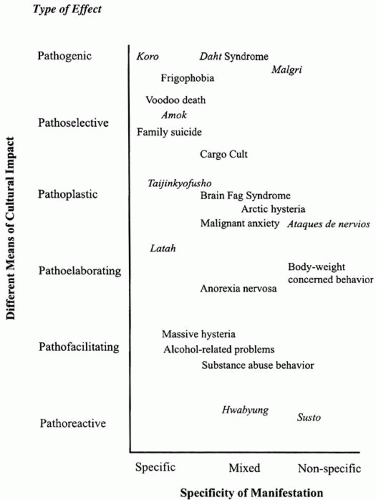

Fig. 4.16.1 Position of culture-related syndromes according to two parameters (This article was published in Handbook of Cultural Psychiatry, Tsend, W.S., copyright Elsevier (2001).) |

Academically identified culture-related specific syndromes can be compared according to two parameters, namely, the different means of cultural impact and the specificity of the manifestation. It will be useful to determine the basic ways culture contributes to the psychopathology, namely: pathogenic, pathoselective, pathoplastic, pathoelaborating, pathofacilitating, or pathoreactive effects; and to what extent the manifested syndrome is: specific, mixed, or non-specific (Fig. 4.16.1). For example, the primary cultural contribution to koro is a pathogenic effect with specific manifestation; to latah a pathoelaborating effect with specific manifestation; and to susto a pathoreactive effect with non-specific manifestation.

Culture-related beliefs as causes of the occurrence (pathogenetic effects)

(a) Koro (genital-retraction anxiety disorder)

(i) Definition

Koro is a Malay term which means the head of a turtle, symbolizing the male sexual organ which can ‘shrink’. Clinically koro refers to the psychiatric condition in which the patient is morbidly concerned that his penis is shrinking excessively and subsequently dangerous consequences (such as death) might occur. The manifested symptoms may vary from simple excessive concern to obsessive/hypochondriac concern, intense anxiety, or a panic condition related to the shrinking of the penis. Clinically, this is usually a benign (non-psychotic) condition that occurs in individual, as a sporadic case, but occasionally it may grow to epidemic proportions, so that several hundreds or a thousand people may develop this disorder in a panic manner within a limited time of several weeks or several months. The majority of cases are young males who fear that their penises are shrinking. However, the organ concerned may be any protruding part of the body, such as the nose or ear (particularly when patients are prepuberty children) or the nipples or labia (in females).

Sporadic occurrences of female koro cases have never been reported. However, in koro epidemics, a small portion of the victims may be female.(7,8) In those cases, the female patients demonstrate slightly different clinical pictures, mainly focusing on the retraction of the nipples and some on the labia. The clinical condition is characterized by a more or less hysterical panic, associated with multiple somatic symptoms, a bewitched feeling, or the misinterpretation or accusation by others of being bewitched.

(ii) Geographic and ethnic group distribution

Cultural psychiatrists originally considered koro to be a culture-bound disorder related only to the Chinese. Most Chinese investigators have taken the view that the disorder is related to the Chinese cultural belief in suoyang, literally means shrinkage of yang organ due to excess loss of Yang (male) element. It has been speculated further that the occurrence of koro among people in South Asian countries, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, was the result of Chinese migrants. However, this cultural-diffusion view is doubted now, since koro epidemics have been reported in Thailand and India as well, involving non-Chinese victims.

As a result of the dissemination of knowledge about koro as a culture-bound syndrome, there is increased literature reporting so-called koro cases from various ethnic groups around the world, such as from the United Kingdom, Canada, and Israel. However, it was pointed out that among the cases reported, all suffered primarily from many psychiatric conditions: affective disorders, schizophrenia and anxiety disorders, drug abuse, or organic brain disorders. Therefore, they were referred as having koro-like symptoms, not exactly the same as the koro syndrome. It is necessary for clinicians to recognize that koro is referred to on different levels as: a symptom, a syndrome, or an epidemic disorder.

(iii) Epidemic of koro

Koro attack may occur occasionally as endemic or epidemic, involving many victims. Epidemic koro has been observed in several areas: Guangdong area of China, Singapore, Thailand, and India. As an epidemic, it is manifested as a panic state rather than an anxiety or obsessive state. The epidemic koro has tended to occur when there

was socio-political stress within the epidemic areas, and an outburst of koro by a group of people may be interpreted as a way to deal with the social stress that they encountered.

was socio-political stress within the epidemic areas, and an outburst of koro by a group of people may be interpreted as a way to deal with the social stress that they encountered.

(iv) Diagnostic issue

Clinicians habitually try to fit pathologies into certain diagnostic categories. Because the patient, based on his misinterpretation, is morbidly preoccupied with the idea that certain ill-effects may occur due to the excessive retraction of his genital organ, the condition may, in a broad sense, be classified as a hypochondriacal disorder as defined in DSM-IV. The condition is also similar to a body dysmorphic disorder, as the patient is preoccupied with a culturally induced, imagined defect in his physical condition. If the focus is on how the patient reacts emotionally, how he responds to the culture-genic stress, with fear, anxiety, or a panic state, anxiety disorder may be considered. However, when we try to categorize culture-related specific syndromes according to the existing nosologically oriented classification system, their meaning and purpose are lost.

(v) Therapy

As for therapy of sporadic individual cases, assurance may be provided or medical knowledge offered in the form of educational counselling to eliminate the patient’s concern about impending death. This supportive therapy may work in many cases, but, for someone who firmly believes the koro concept, it may not. In general, a young, unmarried male, who lacks adequate psychosexual knowledge and experience, will respond favourably to therapy. If necessary, it is desirable to work on issues such as the patient’s self-image, self-confidence, or his masculinity.

(b) Dhat syndrome (semen-loss anxiety)

Very closely related to the genital-retraction anxiety disorder (koro) is the semen-loss or semen-leaking anxiety disorder, or spermatorrhea, also known by its Indian folk name, dhat syndrome. The dhat syndrome refers to the clinical condition in which the patient is morbidly preoccupied with the excessive loss of semen from an improper form of leaking, such as nocturnal emissions, masturbation, or urination. The underlying anxiety is based on the cultural belief that excessive semen loss will result in illness. Therefore, it is a pathogenically induced psychological disorder.(9,10) The medical term spermatorrhea is a misnomer, as there is no actual problem of sperm leakage from a urological point of view.

From a clinical point of view, the patients are predominantly young males who present vague, multiple somatic symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, anxiety, loss of appetite, and feelings of guilt (about having indulged in sexual acts such as masturbation or having sex with prostitutes). Some also complain of sexual dysfunction (impotence or premature ejaculation). The chief complaint is often that the urine is opaque, which is attributed to the presence of semen. The patient attributes the passing of semen in the urine to his excessive indulgence in masturbation or other socially defined sexual improprieties.(11) The syndrome is also widespread in Nepal, Sri Lanka (where it is referred to as prameha disease), Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

(c) Sorcery fear and voodoo death (magic-fear-induced death)

The peculiar phenomenon of voodoo death refers to the sudden occurrence of death associated with taboo-breaking or curse fear. It is based on the belief in witchcraft, the putative power to bring about misfortune, disability, and even death through spiritual mechanisms.(12) A severe fear reaction may result from such beliefs, which may actually end in death. From a psychosomatic point of view, it would be psychogenically induced death. From a cultural psychiatric perspective, it is another example of culture-induced morbid fear reaction.

Medically it has been recognized that sudden death was related to psychological stress occurring during experiences of acute grief, the threat of the loss of a close person, personal danger, or other stressful situations. It has been speculated that the cause of death was possibly from natural causes; the possible use of poisons due to sorcery or witchcraft; excessive fear reaction; or death from dehydration or existing physical illness due to old age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree