Chapter 1 Introduction: current concepts and clinical decision making in electrotherapy

INTRODUCTION

From the published and experiential evidence, it appears that electrotherapy can be clinically effective and need not be written off as something that is ‘old fashioned’ and that no longer deserves a place in the therapeutic tool kit. That it can be applied in a clinically effective manner is evidenced in the chapters that follow. That it can also be delivered in an ineffectual manner is something that will be recognised by practitioners from many disciplines. The evidence would suggest that when the appropriate modality is applied at the ‘right’ dose for the presenting problem, it can make a significant contribution to the improvement and well being of the patient. The fact that it does not work in all cases is not surprising at all. This would be a common feature of any therapy – whether manual therapy, exercise or drug therapy. If one were to use a particular manual therapy technique for patient X, and the next day or the next week, when X returns, there was no improvement, it would not mean that all manual therapy was a waste of time, or even that the therapist was incompetent. There are patients who fail to respond to therapy A, but do very well with therapy B. The reasons for these individual differences are poorly understood, but certainly add to the richness of clinical experience. If therapy was simply a matter of applying the right recipe to the patient presenting with a given problem, clinical practice would lose a deal of its attractiveness. For any therapeutic intervention to be effective there is the need for a clear assessment, a rationalisation of the problem(s), and the construction of a proposed treatment plan that matches the needs of the individual taking into account their holistic circumstances, not just their presenting signs and symptoms. The applied intervention is that which is deemed to be most likely to be effective. This is no guarantee that there will be 100% success, but the best odds for a beneficial outcome. The thinking therapist then re-evaluates the outcomes as the treatment progresses, modifying the treatment package in the light of these results.

The research evidence suggests that electrotherapy can be effective as an element of treatment. Further work is needed to evaluate the combinations – or treatment packages – that are most effective. Practitioners will have, from their own experience, ideas about combinations that are more or less effective. This is the source of the richness of therapeutic experience and until substantially more work has been completed – both in the laboratory and in clinical practice, using reductionist, holistic and pragmatic methodologies – the full story is unlikely to emerge.

MODELS OF ELECTROTHERAPY

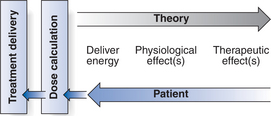

In principle, the model identifies that the delivery of energy from a machine or device is the start point of the intervention (Fig. 1.1). The energy entry to the tissues results in a change in one or more physiological events. Some are very specific whereas others are multifaceted. The capacity of the energy to influence physiological events is key to the processes of all electrotherapy modalities and will be reflected throughout this publication. The physiological shift that results from the energy delivery is used in practice to generate what is commonly referred to as a therapeutic effect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree