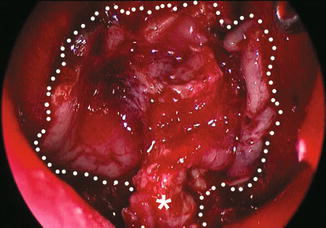

Fig. 5.1

Endoscopic view of the surgical field after the removal of a large pituitary adenoma. Note the residual gland pushed toward the left wall of the sella (a). Endoscopic close-up view of the suprasellar cistern (b). D dorsum sellae, Sc suprasellar cistern, Pg pituitary gland

Intra- and suprasellar fibrous adenoma and giant adenomas with a prevalent suprasellar extension can be unlocked through an extended endoscopic approach to the planum, by expanding the bone window upon the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale. After internal debulking, the tumour is gently pulled downward and removed through an extracapsular dissection. The endoscopic multiangled close-up view allows precise and effective dissection of tumour capsule from the arachnoid covering the optic pathway and anterior cerebral artery-anterior communicating artery complex.

The endoscopic approach offers the possibility to manage even wide parasellar adenomatous extension; in such cases, the medial wall of the cavernous sinus has been already fenestrated by the tumour, mainly at level of its superior aspect, which is thinner, thus representing a “natural gate” toward the medial compartment of the cavernous sinus [48]. The venous bleeding indicates the completeness of tumour removal and is easily controlled with warm saline irrigation, cottonoid compression and, if brisky, with thrombin-gelatine matrix (Floseal, Baxter BioSurgery, Vienna, Austria) [10].

When the pituitary adenoma extends to the lateral compartment of the cavernous sinus, it can be delivered through an ipsilateral transethmoid transpterygoid route [13, 25, 36]. The endonasal corridor is widened along the coronal plane by removing the posterior ethmoid and drilling the root of the medial pterygoid process; the lateral recess of the sphenoid sinus is exposed, and the lateral compartment of the cavernous sinus is entered through a quadrangular safety area, bordered superiorly by V2, inferiorly by the vidian nerve and posteriorly by the parasellar and paraclival carotid artery [13, 39].

After tumour removal, the sellar reconstruction is required mainly when an intraoperative CSF leak has occurred. Autologous or heterologous materials, either resorbable or not, are used, if necessary, to achieve a safe and effective sellar reconstruction. The aim of the repair is to provide a watertight closure, reduce the dead space and prevent the descent of the chiasm into the sellar cavity. Overpacking and subsequent damage to the optic chiasm should be avoided. In addition to accurately packing the sellar cavity, it is necessary to close the sellar floor. Different techniques are used (intra- and/or extradural closure of the sella and packing of the sella with or without packing of the sphenoid sinus), depending on the size of osteodural defect and of the dead space inside the sella [9, 15].

5.3 Craniopharyngiomas

The current management of craniopharyngioma aims for complete resection, which remains the gold standard, although recurrence is a common event [8, 16, 19, 26, 28, 29]. The multitude of operative approaches to these midline deep-seated lesions reflects their challenging nature. Several factors can guide a case-specific choice of the approach:

Patient’s characteristics: age, pituitary function and ophthalmologic status, degree of hypothalamic dysfunction, primary or recurrent pathology and in the latter, history of previous surgery and/or radiosurgery

Lesion’s configuration: consistency, presence of cysts and calcification, dimension, growth direction, lateral extension, relationship with the ICA and with the third ventricle, pial invasion

Surgeon’s personal experience

Systematic review of these factors has a critical role when designing the appropriate surgical approach.

A pure intrasellar lesion with enlargement of the sella turcica is a well-established indication for the standard transphenoidal approach.

In case of intra-suprasellar infradiaphragmatic lesion, the sella turcica is enlarged, and the diaphragma sellae is pushed upward. In the majority of cases, a standard transphenoidal approach allows the removal of the lesion since the suprasellar part usually collapses down into the sella after the removal of the intrasellar compartment of the lesion. In case of suprasellar craniopharyngiomas, some selected cases can be treated using the transtuberculum-transplanum approach. The main steps of the procedure are:

Creation of a wide endonasal corridor with middle turbinectomy (uni- or bilateral), posterior septectomy and a wide anterior sphenoidotomy [35].

Drilling of the sellar floor and of the tuberculum sellae, with bone removal extended between the medial opto-carotid recesses (Fig. 5.2). We routinely use some additional tools (neuronavigator, dedicated instruments, micro-Doppler probe) that improve safety and effectiveness of the procedure.

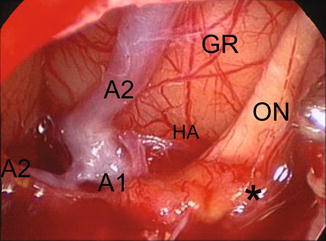

Fig. 5.2

Intra-op image shows suprasellar neurovascular structures after the removal of a suprasellar prechiasmatic craniopharyngioma. A1 precommunicating segment of the anterior cerebral artery, A2 postcommunicating segment of the anterior cerebral artery, HA Heubner’s artery, GR gyrus rectus, ON optic nerve, asterisk thickened arachnoid

Among supradiaphragmatic lesions, Kassam has recently proposed an approach-based classification useful when removing the craniopharyngioma from the endonasal route; he brings out four main types: pre-, trans- and retroinfundibular and lesions isolated to the third ventricle [37].

In suprasellar prechiasmatic preinfundibular lesions, the transtuberculum-transplanum sphenoidale approach provides a direct midline exposure of the tumour, which is seen immediately after dural opening. The optic nerves and chiasm are usually stretched superiorly by the tumour, and the endoscopic view from below highlights in a safe way the distal branches of the superior hypophyseal arteries, which supply the inferior surface of the optic chiasm and the pars tuberalis of the pituitary; their preservation is critical for the visual and endocrine outcome. As for transcranial techniques, tolerance of the optic system to surgical manipulation depends on its preoperative status: an optic nerve or chiasm already stretched and distorted by adjacent tumour is extremely sensitive to any type of manipulation; however, the endoscopic endonasal technique offers the opportunity to early decompress the nerves and to dissect the tumour from the nerve and not vice versa as usually occurs during transcranial procedures, thus minimizing the surgical manipulation over the optic pathways (Fig. 5.2).

Concerning retrochiasmatic retroinfundibular craniopharyngiomas, the number of surgical classifications and cranial approaches (subfrontal, pterional, transcallosal, transpetrosal) proposed for such lesions over the years reflects the difficulty in exposing them widely through a single approach. The endoscopic endonasal route provides a coaxial route to the lesion extension. The starting gate is the pituitary stalk [37]; depending on the pattern of growth of the lesion, intra- and/or para-pituitary stalk routes can be followed toward the retrosellar and even intraventricular area (Fig. 5.3).

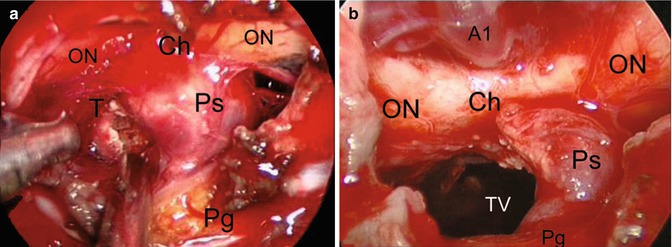

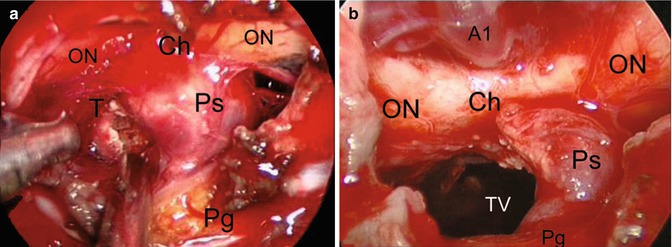

Fig. 5.3

Intra-op image during the removal of a suprasellar retroinfundibular craniopharyngioma before (a) and after (b) tumour removal. ON optic nerve, Ch chiasm, Ps pituitary stalk, T tumour, Pg pituitary gland, A1 precommunicating segment of the anterior cerebral artery, TV third ventricle

When dealing with retroinfundibular lesions, the pituitary stalk can be preserved by running the endoscope and instruments along the para-pituitary stalk corridors and/or by mobilizing the gland upward as proposed by Kassam et al. [38]. However, such procedure requires extensive experience in endonasal skull base surgery. Furthermore, depending on downward extension in the posterior cranial fossa, retroinfundibular lesions can also require drilling of the dorsum sellae and removal of the posterior clinoids [37].

When the lesion grows into the infundibulum, the pituitary stalk is usually enlarged by the tumour, which creates a corridor to enter the ventricular chamber; since it may be hard to understand how the third ventricle can be unlocked through the nose, some considerations supporting such strategy have to be clarified. When dealing with a lesion inside the third ventricle, the possibility to apply the endoscopic endonasal technique depends on two main factors:

The position of the floor of the third ventricle

The size and position of the infundibulum and of the pituitary stalk

A craniopharyngioma which displaces the floor of the third ventricle inferiorly and enlarges the infundibulum, pushing it over the sella, creates the surgical space needed to face the lesion just after the dural opening over the suprasellar area.

Some points have to be considered when approaching such intraventricular lesions:

1.

The dura should be opened carefully in the suprasellar area since the chiasm may lie just behind the dura in a prefixed position, pushed anteriorly by the intraventricular lesion; preoperative MRI is of value to highlight the distance between the tuberculum sellae and the chiasm.

2.

When dissecting the tumour from the floor of the third ventricle, the latter should never be violated at the level of the mammillary bodies or even more posteriorly to avoid the risk of brain stem injury.

3.

Invasive fingerlike tumoural infiltration and/or gliotic tissue adherent to the hypothalamus represents a contraindication to further dissection.

5.4 Reconstruction in Extended Approaches

After tumour removal and careful haemostasis, the reconstruction of the osteodural defect is tailored in order to avoid CSF leakage. The latter is related to the degree of subarachnoid dissection and/or opening of the third ventricle.

In standard transphenoidal surgery, the integrity of the subarachnoid space is usually preserved, whereas in extended transplanum approaches wide arachnoidal opening is a prerequisite to a successful surgery. In the transtuberculum-transplanum approach, the bone window has an irregular shape and is bordered by neurovascular structures such as the optic nerve and the internal carotid artery. The reconstruction technique comprises the following main steps:

1.

Arachnoid sealing. A thin layer of fibrin glue (Tisseel, Baxter, Vienna, Austria) is injected intradurally to create a first barrier to CSF leakage.

2.

The osteodural defect is reconstructed extradurally with a foil of collagen-derived dural substitute which exceeds the bone defect, held in place with a fragment of bone substitute (Lactosorb®, Walter Lorenz Surgical, INC., Florida, USA) which fits the bone opening.

3.

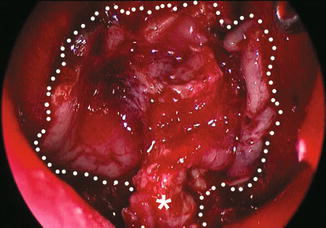

The whole skull base defect is then covered with a vascularized nasoseptal flap, which is designed preoperatively, depending on the size of the craniectomy; due to its shrinkage, it should be about 30 % larger than the defect (Fig. 5.4) [43].

Fig. 5.4

Intra-op image showing a vascularized nasoseptal flap. Dotted line borders of the flap, asterisk vascular pedicle containing the septal branches of the sphenopalatine artery

5.5 Future Perspectives

Despite significant improvements in medical therapy, surgery still has an important role in the management of pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas. Further development of the endoscopic techniques will be driven by several technological advances such as high-definition intraoperative digital imaging, three-dimensional endoscopy and dedicated instruments [47, 51]. Another important determinant in improving the global outcomes of such techniques is the advancement in the anatomic research, which is of utmost importance to define the advantages and limits of skull base surgery with the endoscopic endonasal technique. At the same time, the evolution of reconstruction materials and of reconstruction techniques will greatly affect this still critical step of the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree