Drinking within the population. The areas are not accurate representations of the relative proportions of those exhibiting differing drinking behaviours because this varies among populations.

Hazardous drinking

Hazardous drinking refers to drinking more than a certain limit that places the individual at risk of incurring harm (Edwards, Arif, & Hodgson, 1981). The WHO (1994) Lexicon of Alcohol and Drug Terms described hazardous use of a substance as:

A pattern of substance use that increases the risk of harmful consequences for the user. Some would limit the consequences to physical and mental health (as in harmful use); some would also include social consequences. In contrast to harmful use, hazardous use refers to patterns of use that are of public health significance despite the absence of any current disorder in the individual user.

Hazardous drinking usually applies to anyone drinking more than the recommended levels. One common pattern of hazardous use is “binge drinking,” a term and its synonyms (e.g., bout, bender, spree) used to describe drinking “a lot” in everyday speech. Clinical and scientific definitions vary nationally.

The U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking that brings blood alcohol concentration levels to 0.8 mg/dL, which typically occurs after four drinks for a woman or five drinks for a man, consumed over 2 hours or less. Binge drinking is not represented in Figure 1.1 or in the diagnostic criteria because it is not specific to any level of consumption: hazardous, harmful, and dependent drinkers may all engage in drinking binges.

Hazardous drinkers do not usually seek help for an alcohol problem. They are typically identified opportunistically in the primary care, general hospital, and other nonspecialty care settings (see Chapter 9).

Harmful drinking

Unlike hazardous drinking, harmful drinking is known to have damaged the drinker (Edwards, Arif, & Hodgson 1981). Harmful psychoactive substance use (in this case, alcohol) is a diagnostic term within the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10):

A pattern of psychoactive substance use that is causing damage to health. The damage may be physical (as in cases of hepatitis from the self-administration of injected drugs) or mental (e.g. depressive episodes secondary to heavy consumption of alcohol). (World Health Organization, 1992, pp. 74–75)

Although harmful use often has adverse social consequences, social consequences in themselves are not sufficient to justify a diagnosis of harmful use. The parallel diagnosis in the fourth iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) was alcohol abuse: a “maladaptive pattern of alcohol use in the absence of a diagnosis of alcohol dependence” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

However, DSM-5 has replaced the diagnoses of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence with alcohol use disorder (AUD). AUDs exist on a continuum, with mild, moderate, and severe subclassifications. Although many criteria remain the same in DSM-5, legal consequences have been removed and the term “craving” added (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Of the 11 criteria, 2–3 are required for a diagnosis of mild AUD, 4–5 of moderate, and 6 or more for a diagnosis of severe disorder (see Table 1.3). As a consequence of these changes in DSM-5, an individual could now meet criteria for having an AUD with a level of drinking that would not have met DSM-IV alcohol abuse criteria. ICD-11 is in development and appears likely to maintaining the ICD-10 categories of harmful use and dependence.

Alcohol dependence (syndrome)

The top of the pyramid in Figure 1.1 represents the dependent drinker. These individuals typically have a history of alcohol-related problems and constitute most of the caseload in specialty alcohol treatment services (although they also present elsewhere). Moderately dependent drinkers will show evidence of tolerance, alcohol withdrawal, and impaired control over drinking. Severely dependent drinkers typically have long-standing problems and a history of repeated treatment episodes.

Based somewhat on the traditions imposed by different diagnostic systems, some scientific and clinical work on this population of drinkers has been organized under the concept of “alcohol dependence” (e.g., studies using the DSM-IV), whereas other work has been informed by the concept of the “alcohol dependence syndrome” (e.g., studies using the ICD-10). Etymologically, the English word “syndrome” derives from the Greek syn meaning “together” and dromos meaning “running.” Thus, the “alcohol dependence syndrome” as operationally defined by the ICD-10 is a collection of symptoms that “run together,” including a compulsion to take alcohol, difficulty with control, withdrawal symptoms and relief drinking, tolerance, predominance, and persisting use despite evidence of harm (see Table 1.4). Nonetheless, the ICD-10 requires only three of the criteria to be present, and so perhaps the strict definition of syndrome as “consistently occurring together” should not apply to the ICD-10. Many people diagnosed as alcohol dependent under ICD-10 will meet the DSM-5 criteria for severe AUD, which are similar and include tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, taking of alcohol in greater amounts than intended, desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down, spending extensive time in activities to obtain alcohol or recover from consuming it, giving up of activities, and persistent use despite associated problems (see Table 1.3).

| A cluster of physiological, behavioural, and cognitive phenomena in which the use of alcohol takes a much higher priority for a given individual than other behaviours that once had greater value. A central descriptive characteristic of the dependence syndrome is the desire (often strong, sometimes overpowering) to take alcohol. There may be evidence that the return to alcohol use after a period of abstinence leads to a more rapid reappearance of other features of the syndrome than occurs with nondependent individuals. |

| Three or more of the following have been experienced or exhibited at some time in the previous year. |

| (a) Strong desire or sense of compulsion to take alcohol. |

| (b) Difficulties in controlling alcohol-taking behaviour in terms of its onset, termination, or level of use. |

| (c) A physiological withdrawal state when alcohol use has ceased or has been reduced, as evidenced by: the characteristic withdrawal syndrome for alcohol or use of the same (or a closely related substance) with the intention of relieving or avoiding withdrawal symptoms. |

| (d) Evidence of tolerance, such that increased dosages are required in order to achieve effects originally produced by lower dosages. |

| (e) Progressive neglect of alternative pleasures or interests because of alcohol use, increased amount of time necessary to obtain or take alcohol or recover from its effects. |

| (f) Persisting with alcohol use despite clear evidence of overtly harmful consequences, such as harm to the liver through excessive drinking, depressive mood states consequent to heavy substance misuse, or alcohol-related impairment of cognitive functioning. Efforts should be made to determine if the user was actually, or could be expected to be, aware of the nature and extent of the harm. |

Making the diagnosis of dependence should not be a mechanistic tick-box exercise. Dependence cannot be conceived as “not present” or “present,” with the diagnostic task then completed. Clinicians must recognize the subtleties of symptomatology, which will reveal not only whether this condition is there at all but, if it exists, the degree of its development. What has also to be learnt is how the syndrome’s manifestations are molded by personality, environmental influence, or cultural forces. The ability to comprehend variations on the theme constitutes the real art of clinical diagnosis. For instance, craving may have a different meaning to the clinician and the patient, and alcohol-related consequences may depend on context. If clinicians cannot recognize degrees of dependence (or severity of AUD), they will be unable to adapt their approach to the particular individual, and they may retreat into seeing “alcoholism” as a fixed entity from which all individuals with drinking problems are presumed to suffer, for whom the universal goal must be total abstinence, and with the treatment offered being universally intensive.

Clinical genesis of the concept

A syndrome is a descriptive clinical formulation that is, at least initially, likely to be agnostic as to causation or pathology. The existence of alcohol dependence has been evident to acute observers for many years (see Box 1.1), but, in the 1970s, a detailed clinical description was enunciated within a syndrome model by Edwards and Gross (1976). These scholars’ clinical observations revealed a repeated clustering of signs and symptoms in certain heavy drinkers. They postulated that the syndrome existed in degrees of severity rather than as a categorical absolute, that its presentation could be shaped by pathoplastic influences rather than its being concrete and invariable, and that alcohol dependence should be conceptually distinguished from alcohol-related problems. This clinically derived formulation was at that stage designated as only provisional, and, within the general research tradition of psychiatric taxonomy, the validity of the syndrome had then to be determined.

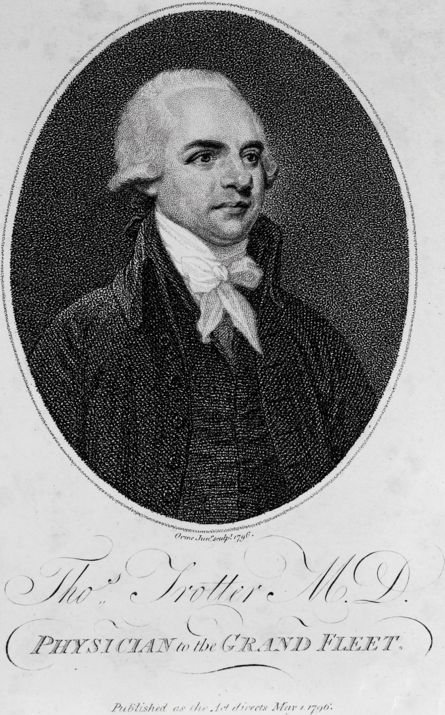

Beginning in the late seventeenth century, the growing availability of inexpensive strong spirits triggered an epidemic of drinking problems across England. Reformers responded with efforts to limit the supply of alcohol (e.g., The Gin Act of 1751) and calls for religious and moral renewal of the drinking population. Not until the turn of the nineteenth century did a book-length discussion adopt an explicitly medical perspective on heavy drinking. An Essay, Medical, Philosophical and Chemical, on Drunkenness and Its Effects on the Human Body was penned by Dr. Thomas Trotter (1804) who had recently retired from a distinguished career as Physician to the Royal Navy (Vale & Edwards, 2011).

Trotter detailed the possible medical sequelae of chronic drunkenness, including ulcers, jaundice, and melancholy (i.e., depression), illustrating his points with vivid accounts of individual cases. In unpacking the etiology of problem drinking, Trotter blamed neither spirits nor the drinker’s bad character. Rather, he understood problem drinking as a learned habit made more tenacious by psychological forces. His concept of “disease” was not therefore strictly biological, but referred instead to psychological discomfort (Vale & Edwards, 2011).

Portrait of Thomas Trotter used with permission of the Wellcome library.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree