CHAPTER 11 DELIRIUM

Delirium may be caused by specific brain injury (e.g., herpes simplex encephalitis), but more often, delirium is a nonspecific response of the brain to challenges from systemic illness or medications. Delirium can occur in otherwise normal brains with extreme physiological challenge (e.g., intensive care admission), but in diseased brains (e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia), even apparently trivial challenges, such as a urinary tract infection or constipation, may trigger delirium. Delirium may be caused by just one factor (e.g., recreational drug use) but commonly appears to result from a combination of harmful factors.

DEFINITION

Many terms have been used to describe the delirious state, including acute organic brain syndrome, acute confusional state, toxic psychosis, intensive care unit (ICU) syndrome, and postoperative psychosis. This variation reflects the difficulty in describing the syndrome or syndromes that are now most commonly called delirium. The most common definition used in delirium research is that of the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (Fig. 11-1).1

Figure 11-1 Rights were not granted to include this figure in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for delirium. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

The key features of delirium are acute change in cognitive status, fluctuation in consciousness, deficits in attention, and perceptual disturbances.1 Nonarbitrary definitions of these features, especially consciousness and attention, are lacking, and this limits the ability to define delirium precisely.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

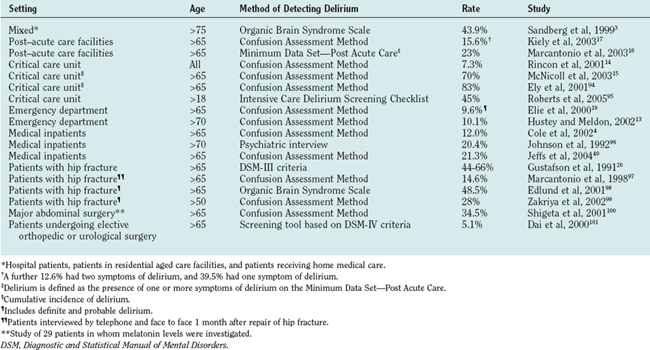

Prevalence and Incidence

Delirium is common (Table 11-1). The prevalence of delirium in hospitalized older patients is 14% to 60%; the rates are higher in surgical patients (particularly those with hip fracture or requiring emergency surgery).2–6 Approximately 1 per 10 elderly patients presenting to hospital are delirious, and a further 10% to 40% develop delirium while hospitalized.7 Delirium occurs in up to 45% of hospitalized patients with preexisting cognitive impairment.8 Delirium is even more common in patients nearing the end of life, occurring in up to four fifths of such patients.9,10 Delirium occurs in 10% of patients presenting to emergency departments and is almost universal in intensive care units.11–16 Of patients admitted to post–acute care facilities, 16% have a diagnosis of delirium, and a further 23% to 53% have symptoms of delirium at the time of admission.17,18

Despite the high incidence and prevalence of delirium, it remains underrecognized by clinicians—up to 90% of cases in inpatients are missed.13,19–26 Furthermore, patients are discharged home from the emergency department without delirium being recognized, and this has been linked to increased mortality.12,13,23

Clinical Syndromes

Delirium is not a homogenous disorder; rather, it is a complex clinical syndrome with diverse etiologies and presentations. Delirium tremens is the classic picture of delirium with which most clinicians are familiar. Agitation; being out of touch with reality, with visual, tactile, and auditory hallucinations; obvious fear; and suspicion and mistrust of others typify the hyperactive form of delirium. The hypoactive form of delirium is recognized from apathy in patients with marked cognitive impairment. Hypoactive delirium is easily missed, inasmuch as there are no behavioral disturbances that bring attention to the patients and the patients seldom volunteer that they are experiencing psychotic thoughts or bizarre sensations.

About 25% of cases of delirium are of the hyperactive form, another 25% are of the hypoactive form, and the remainder of patients with delirium have both hyperactive and hypoactive features.3,27,28 The cause of delirium cannot be reliably diagnosed from the subtype observed, although drug withdrawal states more commonly manifest with the hyperactive form and metabolic encephalopathies with the hypoactive form.28,29 Infection may manifest with either form of delirium.30,31

Patients who have some of the key features of delirium but do not fully satisfy the DSM-IV criteria experience adverse events similar to those who do meet the criteria. This “subsyndromal delirium” has been associated with poor outcomes, and there is probably a relationship between the number of features present and the risk of adverse outcomes.32,33

Course

Delirium often lasts for a few days or a week, but some patients experience prolonged delirium. One study showed that only approximately one fifth of patients have complete resolution of delirium at 6 months.34 Symptoms of memory impairment, inattention, and disorientation may still be present 12 months after an episode of delirium.35 Prolonged delirium leads to diagnostic difficulty, especially when the precipitating event has apparently resolved, and it may be difficult to distinguish delirium from dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies, with its characteristic attentional fluctuations causes particular difficulty (see Chapter 71). Nearly one in five patients has a new diagnosis of dementia in the year after an episode of delirium.36 The existence of prolonged delirium also makes it difficult to predict recovery of individual patients and complicates decisions about rehabilitation potential and long-term care.

Sequelae

Physical

Delirium is associated with major morbidity and mortality. Patients suffering from delirium have an initial mortality rate of up to 26%.37 Twelve months after an episode of delirium, patients are twice as likely to have died than are similar patients who have not had delirium.36,38 Mortality rates as high as 75% three years after an episode of delirium have been reported.39

Complications attributable to delirium include malnutrition, dehydration, pneumonia, pressure sores, and falls. Patients with delirium suffer greater functional decline in hospital, and are more likely to require rehabilitation or long-term residential care.34,40–43 Patients with hyperactive delirium are more likely to fall while hospitalized.30 Patients with hypoactive delirium are generally sicker, remain hospitalized longer, and are more likely to develop pressure sores.30

Social and Economic

Delirium often imposes a heavy burden on the families of those affected as they come to terms with a serious condition that substantially alters the behavior of their family member and that has an uncertain prognosis. It also creates an economic burden for health care systems as a result of increased duration of hospitalization and increased postdischarge costs.44–46

RISK FACTORS

Baseline Vulnerability

Factors that increase vulnerability to delirium include preexisting cognitive impairment, comorbid illness, and sensory deficits (Table 11-2).11,45,47,48

TABLE 11-2 Baseline Vulnerability and Precipitating Factors for Delirium

| Risk Factor* | Adjusted Relative Risk |

|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment/dementia11,45,47,48 | 2.1-5.3 |

| Number of major diagnostic categories45 | 1.7 |

| Depression11,45 | 1.9-3.2 |

| Alcoholism11,45 | 3.3-5.7 |

| Severe medical illness11,58 | 3.5-5.9 |

| Male gender11 | 1.9 |

| Abnormal sodium11,47 | 2.2-6.2 |

| Hearing impairment11 | 1.9 |

| Visual impairment11,48 | 1.7-3.5 |

| Diminished ADL11 | 2.5 |

| Fever or hypothermia47 | 5.0 |

| Psychoactive drug use47 | 3.9 |

| Azotemia/dehydration47 | 2.0-2.9 |

| Use of physical restraints52 | 4.4 |

| Malnutrition52 | 4.0 |

| More than three medications added in 24 hours52 | 2.9 |

| Use of indwelling urinary catheter52 | 2.4 |

| Any iatrogenic event52 | 1.9 |

ADL, activities of daily living.

* References cited as superscripts.

A delirium risk prediction model based on the presence or absence of cognitive impairment, severe illness, visual impairment, and dehydration at the time of admission to hospital shows that when one or two risk factors are present, the rate of incident delirium is 16% to 23%, whereas when three or four risk factors are present, the rate of delirium is 32% to 83%.48 The magnitude of the noxious event or events necessary to produce a delirious episode is inversely proportional to the degree of baseline vulnerability. In vulnerable people, delirium acts as a sensitive, but not specific, indicator of illness.

Precipitating Factors

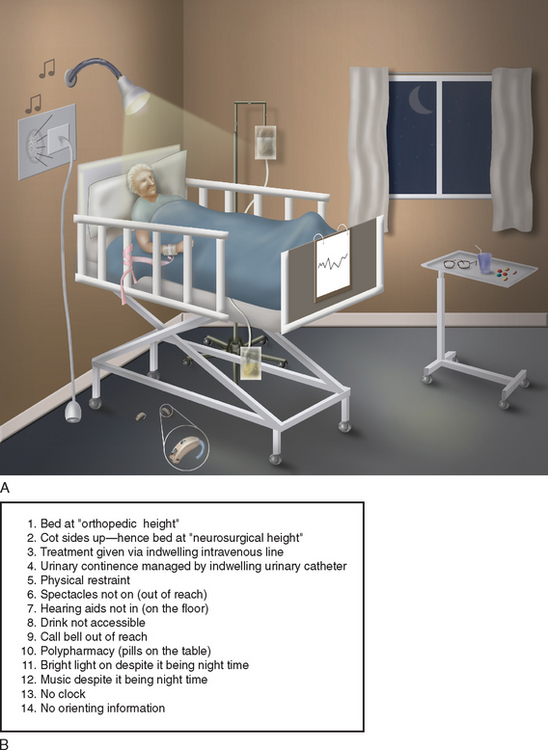

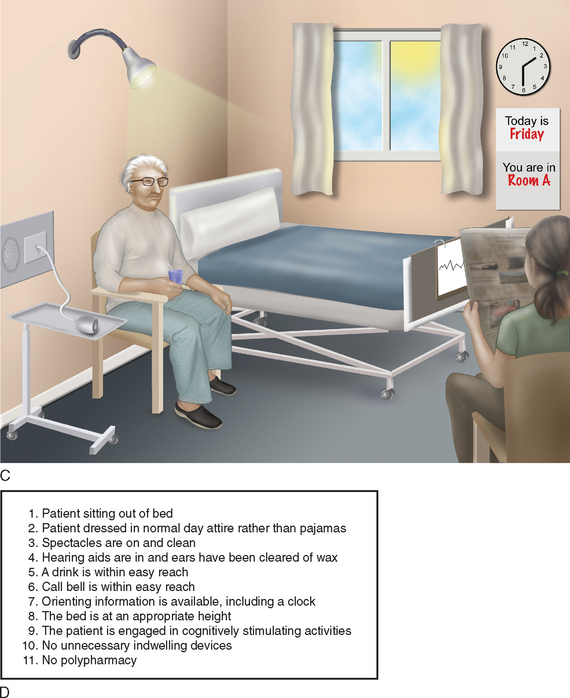

The study of precipitating factors is plagued by confounding variables. The confounding variables (in this case, putative risk factors for delirium, such as prescription of new medications or insertion of a urinary catheter) are related to both the study factor (sickness that necessitates hospitalization and in turn may necessitate the new medications or catheterization) and the outcome factor (delirium that may be caused by the sickness, the interventions, or both). Confounding cannot be adjusted for statistically. Because it would be unethical to subject healthy people to medications, procedures, or hospitalization to test these as independent risk factors for delirium, the evidence regarding precipitating factors comes from descriptive studies. Nonetheless, the weight of evidence shows that many events may precipitate delirium. Delirium is a syndrome with multifactorial etiologies; therefore, in any one patient, it is usual for a number of factors to contribute to delirium.49–51 Five independent risk factors associated with the hospitalization process that appear to increase the risk of developing delirium are (1) the addition of more than three medications in any 24-hour period, (2) the use of physical restraints, (3) the presence of malnutrition, (4) the insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter, and (5) any iatrogenic adverse event.52 The risk of delirium rises proportionately with the number of risk factors. Of importance is that these precipitating factors are potentially avoidable. Patients with three or more precipitating factors have an 8% per day risk of developing delirium.52 Other environmental factors, such as frequent room changes, absence of a clock, or absence of reading glasses, are associated with increased “severity” of delirium.53 Figure 11-2A depicts a hospital environment likely to produce delirium, whereas Figure 11-2C depicts a hospital environment likely to decrease the risk of delirium.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

It is not surprising, in view of the myriad of etiologies and manifestations of delirium, that there is no one satisfactory unifying pathophysiological explanation. In addition, the neural mechanisms by which delirium is produced are poorly understood. To date, proposed pathophysiological mechanisms remain excessively simplistic or, when detailed, cannot explain adequately the various manifestations of delirium. It is not clear whether delirium is the final common pathway for a broad range of insults or whether the different causes of delirium have different pathophysiological processes that are clinically indistinguishable. Delirium is believed to occur as a result of perturbation to systems that have little reserve, and this fits well with the clinical risk prediction tools.

A number of neurotransmitter systems have been implicated in the pathophysiology of delirium. Abnormalities of the cholinergic system are the best studied. The notion that a central cholinergic deficiency leads to delirium is supported clinically by the observation that anticholinergic medications are potent causes of delirium.54,55 Investigators measuring serum anticholinergic activity have reported increased levels associated with the presence of delirium, with levels falling after resolution of delirium.56 Physostigmine, a reversible anticholinesterase inhibitor, has been used to treat anticholinergic delirium with some success.57 Cholinesterase inhibitors have been proposed as a means of treating delirium, with some case reports of success, but, conversely, tacrine has been reported to cause delirium.58,59 Excess dopamine has been implicated in the pathogenesis of delirium, and dopamine antagonists are used to treat delirium.60,61 Both serotonin excess and deficiency have been implicated; serotonin excess appears more likely to be associated with medication-related delirium.55 There is no conclusive evidence to relate either dopamine or γ-amino butyric acid to medical or surgical delirium, but perturbation of its activity has been linked with hepatic encephalopathy and benzodiazepine intoxication or withdrawal states.62,63 Hypercortisolism, such as that occurring in Cushing’s syndrome, is known to have effects on cognition, as well as on mood and sleep, but no decisive link with delirium has been established.55 Animal models such as stressed rats show changes in steroid sensitive hypothalamic neurones that can be prevented by adrenalectomy.64

CLINICAL FEATURES

Cognitive Examination

Fluctuating impairment of sustained directed attention is a key feature of delirium and may become apparent when patients have difficulty attending to questions in the medical interview or are easily distracted during conversation. Attention may be formally assessed by such items such as the Digit Span Memory Test or Trail Making Test.65 Restlessness or picking at the bedclothes may indicate underlying psychotic features. Patients should be questioned with regard to worrying thoughts or unusual sensory experiences in order to elicit the presence of hallucinations or delusions.

Incorporating a screening test for cognition, such as the Mini Mental State Examination, in the initial assessment of hospitalized older patients could substantially improve the detection of delirium.66,67 Poor test performance would prompt clinicians to seek other evidence of delirium.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree