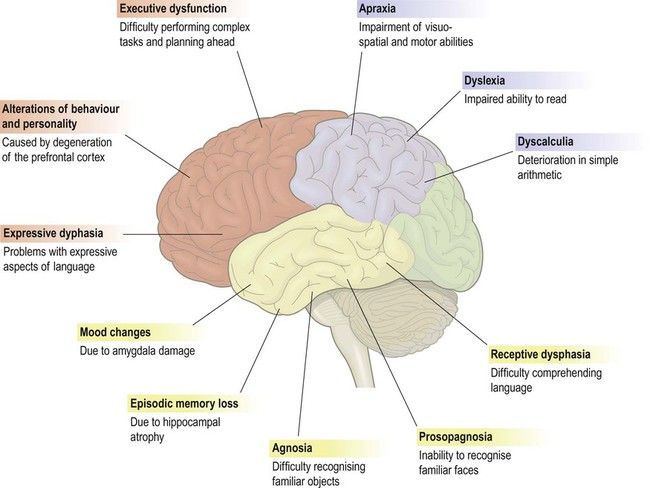

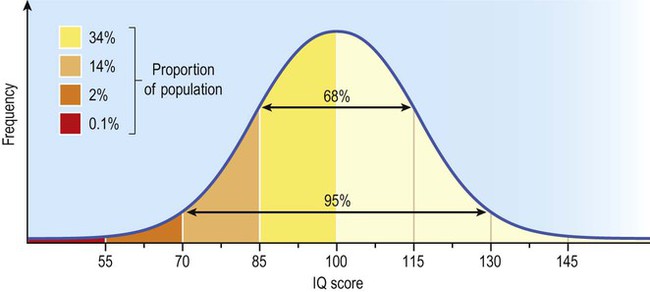

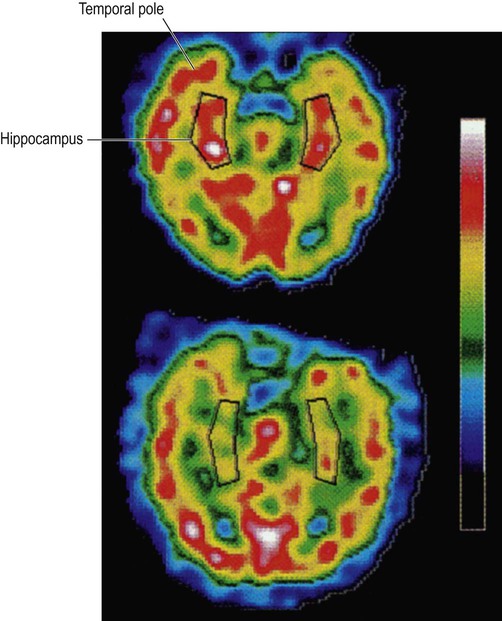

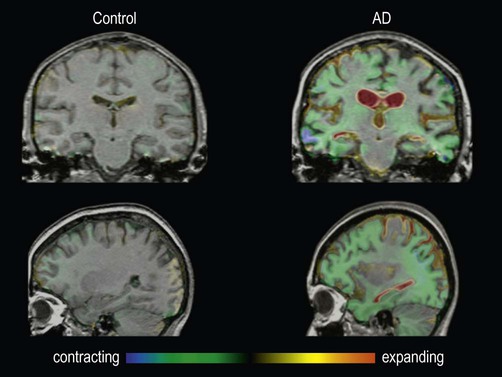

In most cases of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, memory loss is a prominent and early component, but in certain types (e.g. frontotemporal dementia, discussed below) it is relatively spared. Loss of memory is usually accompanied by a marked decline in higher cognitive functions such as reasoning, visuospatial ability and language, together with changes in mood, behaviour and personality. The specific profile of higher cognitive deficits depends on the extent and distribution of pathology in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 12.1). A widely used measure of cognitive ability is the intelligence quotient (IQ) which is a detailed assessment of reasoning, language and memory. Scores are standardized and age-corrected so that the average IQ is 100 and 95% of individuals score between 70 and 130 (Fig. 12.2). Repeated testing can be used to show changes in cognitive ability over time. The main types of dementia are discussed below. The most common cause is Alzheimer’s disease, accounting for around 65% of cases. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) represents a further 20% and vascular dementia is responsible for 10% of cases. The remaining 5% include the frontotemporal dementias, which are an important cause of cognitive decline in people under the age of 60 (accounting for nearly half of cases in this age group, after Alzheimer’s disease). It should be noted that some patients have less severe cognitive impairment that falls short of the criteria for dementia (Clinical Box 12.1). Some forms of cognitive impairment are potentially treatable and should be excluded in the investigation of a patient with suspected dementia. These include nutritional deficiencies (e.g. vitamin B12, folate), endocrine disturbances (such as hypothyroidism), alcohol-related dementia (reversible with abstinence), syphilis (now rare in the developed world), depressive pseudodementia (treatable with antidepressant drugs) and normal pressure hydrocephalus (see Clinical Box 12.2). A ‘routine dementia screen’ therefore includes a range of blood tests and urinalysis, together with an MRI scan of the brain. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is predominantly clinical and post-mortem studies suggest that it is correct in at least 80% of cases. Two variants of Alzheimer’s disease that might cause diagnostic confusion are discussed in Clinical Box 12.3. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease often get lost in familiar places and may forget where they have left things. These features, together with impaired recall of daily events, reflect severe pathology in the medial temporal lobe. This involves structures such as the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus that are involved in spatial navigation and formation of episodic memories (see Ch. 3). Functional brain imaging in early Alzheimer’s disease may show reduced blood flow and glucose metabolism in the posterior temporo-parietal regions and hippocampus (Fig. 12.3), before obvious structural changes are evident on MRI. Over time there is progressive brain atrophy, with ventricular dilatation, cortical thinning and hippocampal atrophy. Longitudinal studies show that people with Alzheimer’s disease lose brain tissue at a rate of 2% per year on average (up to 5% per year in the hippocampus), which is four times higher than in age-matched controls (Fig. 12.4). The most important risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, apart from advancing age, is possession of a particular variant of the Apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) on chromosome 19 (discussed below). It is also more common in people with ischaemic heart disease, in those with limited educational attainments or lower socioeconomic status – and in association with previous head injury (Clinical Box 12.4). A pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is the presence of plaques in the cerebral cortex, consisting of insoluble protein aggregates. Plaques are found in the extracellular space (between neurons) and are predominantly composed of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ). Like all forms of amyloid, the deposits take up the tissue stain Congo red and show apple-green birefringence under polarized light (see Ch. 8). Plaques can be identified using silver staining, but are best demonstrated using immunohistochemistry (antibody labelling). Unlike diffuse plaques, neuritic plaques are strongly associated with cognitive decline. Aβ is also deposited in the walls of blood vessels, leading to cerebral amyloid angiopathy (Clinical Box 12.5). The second major pathological finding in Alzheimer’s disease is the neurofibrillary tangle (NFT). This is a filamentous inclusion composed of the microtubule-associated protein tau, which is normally present in axons (see Ch.5). Tau is a phosphoprotein with 79 serine and threonine phosphorylation sites, less than half of which are normally phosphorylated. Neurofibrillary tangles contain hyperphosphorylated tau in the form of paired helical filaments (PHFs) that resemble twisted ribbons (Fig. 12.7).

Dementia

General aspects

Clinical features

This figure shows some of the common features of dementia that are caused by degenerative changes in different parts of the cerebral cortex (frontal lobe = red, parietal lobe = blue, temporal lobe = yellow). The clinical picture in a particular person depends upon the distribution and severity of the changes.

Assessment and diagnosis

Psychometric testing

Intelligence in the general population has a normal distribution, meaning that scores fall on a symmetrical bell curve. The mean IQ is 100 and the standard deviation is 15, such that 95% of scores fall between 70 and 130.

Types of dementia

Reversible causes

Alzheimer’s disease

Clinical aspects

Visuospatial problems

Neuroimaging

These images were obtained via single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) scanning using a radioactive tracer and show regional cerebral blood flow. The upper image is a normal control subject and the lower image is from a patient with early Alzheimer’s disease. The sections are in the axial (horizontal) plane and pass through the temporal lobe. The black box shows the position of the hippocampus in the medial temporal lobe. From Rodriguez, G. et al.: Hippocampal perfusion in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging (2000, pp. 65–74) with permission.

These are fluid-registered volumetric MRI scans from a 60-year-old patient with Alzheimer’s disease [right] and a normal age-matched control [left]. In each case, two MRI scans were acquired one year apart and have been registered together. Regions of brain loss are shown as blue-green; increases in CSF spaces are shown as red-yellow. In the patient with Alzheimer’s disease, there is marked volume loss in the hippocampi and temporal lobes, with widespread symmetrical atrophy in other parts of the cerebral hemispheres and dilation of the ventricles. The control shows normal age-related atrophy. Courtesy of Professor Nick Fox.

Risk factors

Pathological features

Plaques (Fig. 12.5)

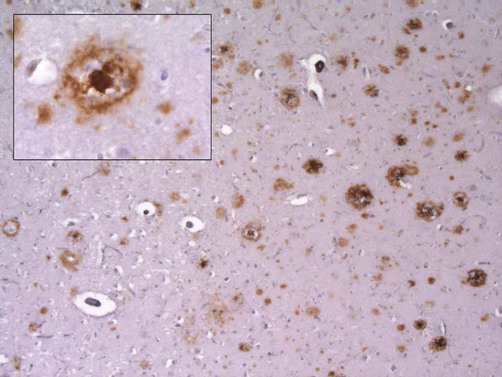

This micrograph demonstrates extensive amyloid beta deposits (amyloid plaques) in the cerebral cortex of a person who died of Alzheimer’s disease. Inset: a single ‘cored plaque’ with a dense central core of amyloid is shown at higher magnification [immunohistochemical preparation for Aβ peptide].

Diffuse plaques are composed of amyloid beta peptide in a non-fibrillary (non-amyloid) form and may be numerous in older people who do not have dementia.

Diffuse plaques are composed of amyloid beta peptide in a non-fibrillary (non-amyloid) form and may be numerous in older people who do not have dementia.

Neuritic plaques are surrounded by abnormal dystrophic neurites (thickened, tortuous neuronal processes) and sometimes have a dense, central core of amyloid (‘cored plaques’; see Fig. 12.5).

Neuritic plaques are surrounded by abnormal dystrophic neurites (thickened, tortuous neuronal processes) and sometimes have a dense, central core of amyloid (‘cored plaques’; see Fig. 12.5).

Neurofibrillary tangles (Fig. 12.6)

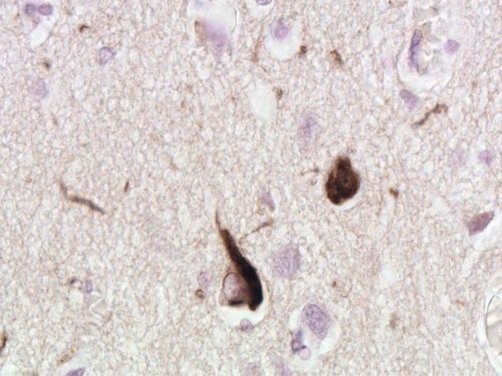

Micrograph showing two cortical neurons containing neurofibrillary tangles. The small, rounded inclusion (right) is a ‘globose’ tangle whilst the larger, more pyramidal-shaped inclusion (left) is a ‘flame’ tangle. The different appearances of the pathological inclusions reflect the shape of the neuronal cell body, which is filled with abnormal tau protein. A few fine ‘neuropil threads’ can also be seen, representing neuronal processes filled with tau [immunohistochemistry for hyperphosphorylated tau protein].

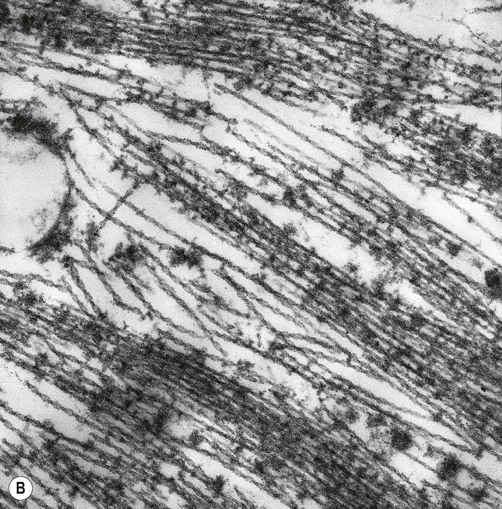

(A) Illustration showing the twisted structure of PHF-tau, which has a diameter of 22 nm and a periodicity of 80 nm; (B) An electron micrograph showing paired helical filament tau. From Ellison and Love: Neuropathology 2e (Mosby 2003) with permission.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dementia

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue