Recognition that a person is experiencing a decline in mental status can often be obvious, especially to the physician who is well acquainted with the patient over a period of years; however, determining the cause of the mental decline is often more challenging and frequently requires a multidisciplinary approach. Some mental status changes such as depression, anxiety, metabolic disorders, and adverse drug interactions are reversible if properly diagnosed and treated, but they can resemble dementia; therefore, if they are not carefully assessed, they can lead to misdiagnosis and improper management. Similarly, there are many different forms of dementia, each with its own cognitive profile and behavioral manifestation, and as new medications that mediate the progression of illness are developed, diagnostic accuracy will become essential to inform treatment decisions. Neuropsychology contributes greatly to the diagnosis of dementia by helping to determine the subtype, nature, and severity of cognitive changes and by characterizing the impact of these deficits on functional aspects of a person’s behavior.

In this chapter, the neuropsychological and behavioral aspects of the most common neurodegenerative dementing illnesses are discussed. Particular emphasis is placed on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) because of the prevalence of this disorder.

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) (

7), the cognitive manifestations of dementia must include impairment in at least two or more of the following domains: short- and long-term memory, abstract thinking, impaired judgment, language or other disturbances of higher cortical functioning, or personality change. Dementia affects an individual’s social and occupational skills as well as the ability for self-care. The cognitive and behavioral disturbances must not be caused by psychiatric mental disorders. Once the physician suspects mental status changes, performs a screening test of mental status, and runs the appropriate battery of medical tests to rule out a reversible process, the patient should be referred for a neuropsychological assessment.

THE ROLE OF THE NEUROPSYCHOLOGIST

Distinguishing between age-related decline, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia such as AD can be difficult, requiring careful evaluation within and across many cognitive functions. There is significant overlap in symptoms among conditions, and it is only by looking at the pattern of functioning within various cognitive and behavioral domains that one can begin to understand the etiology of the disorder. For example, impairment in memory is not specific to any one dementing disorder and should be viewed as a sign of cognitive dysfunction rather than a diagnostic certainty. Problems in free recall can be characteristic of confusional states, depression, or attentional disorders, thereby reflecting a deficit in activating encoding processes. Other memory problems observed in depression, frontal lobe dementias, or a frontal lobe-related deficit can be caused by impairment in retrieval of information. Alternatively, poor performance on a free recall measure could be a symptom of a pure amnestic disorder caused by hippocampal or temporal lobe damage.

Because different cognitive functions subserve functional activities, it is also the role of the neuropsychologist to address functional issues related to a person’s ability to safely carry out instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as driving, medication management, and handling finances, as well as basic activities of daily living (BADL), such as bathing, toileting, and dressing. By definition, dementia interferes with a person’s ability to function normally in everyday life. Skills needed for self-care, social and occupational functioning, and financial management are greatly affected, but the degree and pattern of functional impairment vary widely according to the type and stage of dementia.

In the early and middle stages of a dementing process, evaluation of cognitive status is critical to help ensure the individual’s day-to-day safety, as IADLs and BADLs are strongly associated with changes in executive functioning and memory (

72). When a cognitively impaired person lives alone,

they can be at even greater risk for harm due to self-neglect or disorientation. In an 18-month prospective study examining cognitive predictors of harm in 130 elderly people, 21% of the people had an incident of harm. The study found that three neuropsychological tests that measured executive functioning, recognition memory, and conceptualization were independent risk factors for harm (

146). In the later stages of dementia, a neuropsychological evaluation is usually requested to help with problematic behaviors such as wandering, screaming, or verbal abuse to determine what, if any, behavioral or environmental interventions would be effective in arresting or minimizing such behavior, thereby reducing the use of psychotropic medication to control these behaviors.

DIAGNOSIS

A first step in determining a diagnosis is to understand the nature of the cognitive disturbance and to narrow the causes for the change in mental status. Other than medical and psychiatric history, four key features are important when forming a diagnosis: information regarding when the problems began (i.e., time of onset of initial symptoms); the course of the symptomatology (i.e., insidious, acute presentation with little change, or step-wise); rate of progression of the disorder (i.e., slow or rapidly progressing); and presenting symptoms. Demographic information (e.g., education, occupation) and social history (e.g., living situation, hobbies, alcohol and drug consumption) are also pertinent variables so that test results may be placed within a context.

Tables 21-9 and

21-10 illustrate differences between the pattern of presentation and rate of progression among the various dementing syndromes.

When obtaining the history, even in the early stages of dementia, it is general practice to obtain independent collateral information about cognitive and functional capabilities from a person who knows the patient well. Individuals with dementia often are unaware of their deficits, and self-reports are often not consistent with cognitive performance on testing (

28,

44). Despite the inconsistency between a patient’s self-report and objective test data, it is still important to interview patients because, in the early phase of AD, the patient’s lack of awareness of their functional deficits has been shown to strongly predict a future diagnosis of AD (

144). However, Loewenstein et al. (

88) found that informant reports were not always reliable with regard to functional capacity. They found that caregivers were accurate in predicting the functional performance of patients with AD who were not impaired on objective tests of functional status, but they overestimated the functional abilities of AD patients who were impaired on objective testing. Higher Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

47) scores were associated with caregivers’ overestimation of functional capacities (e.g., ability to tell time, identify currency, make change for a purchase, and use eating utensils).

SCREENING MEASURES

The most commonly used clinical screening tool for the presence of dementia in medical and psychological settings is the Folstein MMSE (

133), which is easily administered in about 5 to 10 minutes. Although it has proved to be highly sensitive to changes in mental status in people over 65, it is most helpful for amnestic forms of dementia. The MMSE is not a good screening test for individuals with other illnesses that primarily involve language dysfunction. One reason for its lack of specificity is that the MMSE does not measure long-term memory, recognition memory, or executive functions (

91). Another drawback to the MMSE is that it is not informative about the level of care needed for patients with mild to moderate levels of dementia. The MMSE has a total score of 30 points, with a score of 23 or lower usually considered indicative of organic dysfunction. However, when age (>80 years) and education (<9 years) are taken into account, the cutoff score suggestive of dementia decreases. It has been suggested that, for people with fewer than 9 years of education, a score of 17 should be considered as the cutoff (

148), whereas a cutoff score of 26 or less has been suggested as optimum to detect mild to moderate dementia in people with higher education (

151). Cultural background has also been shown to affect MMSE scores; Hispanics performed worse than non-Hispanics on the serial subtraction subtest when both groups were matched on education, age, and overall level of dementia. Similar results were found when spelling a word in reverse was substituted for serial subtraction (

67).

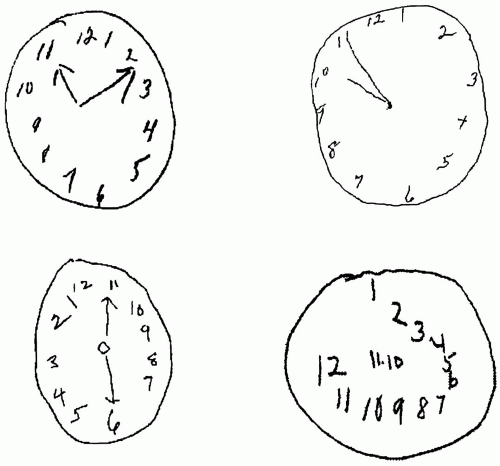

Another quick screening test that is often administered along with the MMSE is the Clock Drawing Test. Together with MMSE scores, Clock Drawing Test performance has been shown to be sensitive to the presence of dementia, especially in those with very mild disease, but, on its own, it is not useful in discriminating between different forms of dementia (

61,

133). There are multiple steps involved in executing this task, and several diverse skills are required, including planning, visual attention, spatial conceptualization, and graphomotor control. In this test, the person is asked to draw the face of a clock, put all the numbers in the correct location, and set the clock to a specific time, either 10 minutes after 11:00 or 20 minutes after 8:00 (

Fig. 21-2). These two times are most sensitive to dementia because they are sensitive to hemi-inattention and spatial conceptualization (

49). Several different scoring systems of the clock have been devised to objectively quantify the presence and level of impairment (

49,

86,

120), one of which (

132) was found to be the most effective in detecting AD when combined with the MMSE.

The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2) (

74) is another frequently used screening measure that takes somewhat longer to administer than the MMSE and Clock Drawing Test but is useful for early detection, differential diagnosis, and staging of dementia for individuals at the lower end of functioning. The DRS-2 is more comprehensive than the MMSE and looks at attention, initiation/perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory in greater depth. The second version of the DRS uses the same test

questions as the first version, but in collaboration with the Mayo Older Americans Normative Studies, the normative data were revised to take age and education into account when interpreting test results. Because the normative data were drawn mostly from white samples in rural or suburban settings, another set of normative data has been developed for older African-Americans to allow for greater diagnostic accuracy (

121).

The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) is used mostly in research settings, but it is mentioned here because of its wide use in drug trials (

127). It is designed to evaluate the severity of both cognitive and noncognitive functions that are characteristic of AD. The scale is comprised of 21 items tapping memory, language and praxis, mood, and behavioral changes (e.g., depression, agitation, psychosis, and vegetative symptoms). It is administered in an interview format and takes about 45 minutes.