Chapter 9

Dementia in Younger People

Epidemiology

Owing to methodological complexities, no epidemiological studies have been conducted to ascertain the prevalence of dementia in young adults. In 2005, based on two clinical studies, it was estimated that just over 15,000 adults aged under 65 years in the UK had dementia. These numbers are predicted to slowly rise to over 17,000 by 2021. It is however generally recognised that these numbers are substantial underestimates, and the true figure could be up to three times higher. The risk of early-onset dementia increases with age but in contrast to older people, it is more common in males (Table 9.1). It may also be more common in black and ethnic minority groups, where 6.1% of dementia is early onset, compared with 2.2% of the total dementia population. The low relative prevalence of early onset dementia (85/100,000), in comparison with functional disorders causing cognitive impairment in younger people such as schizophrenia (4/1000), makes diagnosis particularly challenging.

Table 9.1 Prevalence of early onset dementia per 100,000 UK population.

| Age | F | M | Total |

| 30–34 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 9.4 |

| 35–39 | 9.3 | 6.3 | 7.7 |

| 40–44 | 19.6 | 8.1 | 14.0 |

| 45–49 | 27.3 | 31.8 | 30.4 |

| 50–54 | 55.1 | 62.7 | 58.3 |

| 55–59 | 97.1 | 179.5 | 136.8 |

| 60–64 | 118.0 | 198.9 | 155.7 |

| 45–64 | 66.2 | 99.5 | 84.7 |

Knapp et al. (2007). Reproduced by permission of the Alzheimer’s Society.

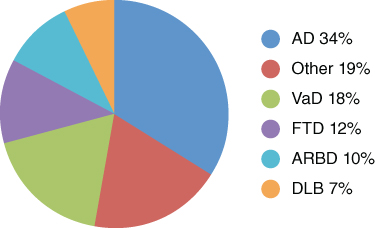

Diagnosis

The vast majority of dementia in older people can be accounted for by three pathologies: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), cerebrovascular disease and Lewy body disease. The situation in younger adults is far more complex. Whilst AD remains the commonest cause, it probably accounts for less than one-half of the diagnoses, and over 30% of cases are due to frontotemporal dementia (FTD) or other rare disorders (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Early-onset dementia diagnostic subtypes. Harvey et al. (2003). Reproduced with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Accurate diagnosis of dementia in younger people is difficult, with incorrect or uncertain diagnoses reported in 30–50% cases. Service users frequently report delays in diagnosis and in being ‘pushed from pillar to post’ in the process (Williams et al., 1999). Diagnosis is particularly difficult in people with a history of functional psychiatric disorder or learning disability and in those from ethnic minority groups, where cultural and linguistic influences on cognitive test performance make interpretation difficult. It is particularly important that functional psychiatric disorders, such as depression, and drugs are excluded, as they are far more common causes of cognitive impairment in younger adults than true dementia. Table 9.2 summarises aetiological subtypes of dementia encountered in younger people based on their earliest or most prominent clinical manifestations.

Table 9.2 Causes of dementia in younger people.

| Clinical presentation | Clinical features | Disorders |

| Amnestic Dementia | Inability to learn and retain new information |

|

| Dysphasic dementia | Problems with combinations of semantic, phonemic and syntactical aspects of speech and language |

|

| Subcortical dementia | Impaired attentional controlExecutive dysfunctionCognitive slowingNeurological deficits |

|

| Parkinsonian dementia | Subcortical pattern of cognitive impairment Extrapyramidal neurological deficit |

|

| Psychiatric dementia | Behavioural change, hallucinations and mood disorder |

|

| Dyspraxic dementia | Inability to perform learnt patterns of motor function including gait disturbance |

|

| Jerky or tremulous dementia | ChoreaTremorJerks |

|

| Ataxic dementia | Incoordination and gait disturbance |

|

| Myoclonic dementias | Myoclonic jerks |

|

| Fluctuating dementia | Features of delirium |

|

| Familial dementia | Familial aggregation, particularly at younger age |

|

| Rapidly progressive dementia | Progression to death within few months to 3–4 years |

|

WKS, Wernike–Korsakoff syndrome; CBS, corticobasal syndrome; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; SOL, space-occupying lesion; CJD, Creutzfeld–Jacob disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; MSA, multi-system atrophy; FTDP-17, frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17; bvFTD, behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia; LE, limbic encephalopathy; SCA, spino-cerebellar ataxia; DRPLA, dentato rubro pallido lysurian atrophy; CTE, chronic traumatic encephalopathy; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Although less than 1% of true dementia may be partly or fully reversible (Box 9.1), nearly all of these cases occur in younger adults (Clarfield, 2003). Consequently, it is essential that younger people with dementia are thoroughly investigated by specialist services, with structural neuroimaging, preferably magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), being a mandatory requirement. Multiprofessional input into the diagnostic process is essential, and may require the coordinated efforts of psychiatrists, neurologists, clinical psychologists, neuroradiologists, and geneticists.

Aetiological subtypes

- Alzheimer’s disease: AD, as in older people, usually presents with insidious onset, progressive impairment of memory for recent events, with particular difficulty in semantic encoding and delayed recall. It may, however, present atypically as posterior cortical atrophy with disturbed visuospatial function (see Chapter 2). Some AD patients also present with prominent language disturbance or executive dysfunction.

- Frontotemporal Dementia: FTD can be broadly divided into two clinical presentations, behavioural and dysphasic. Behavioural variant FTD is characterised by insidious-onset progressive change in personality and behaviour (Box 2). It is important to confirm that there is neuroimaging evidence of frontal or temporal atrophy or similarly located metabolic or blood flow abnormalities, as those who lack these features tend to deteriorate little and may have a different disorder. In the UK, around 40% of cases have a positive family history, and a significant proportion of these will have mutations in the genes for tau or progranulin, or the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat, which is also associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.In progressive aphasias, there is gradual onset, deteriorating language function, which is the predominant symptom during the initial phase of the illness. There are broadly three types: semantic dementia, progressive non-fluent aphasia and logopenic aphasia (Table 9.3).

- Dementias of other aetiology: Dementias occurring in parkinsonism usually have a subcortical pattern of cognitive impairment, as classically described in progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Marked visuoperceptual impairment, fluctuation and recurrent visual hallucinations suggest dementia with Lewy bodies, whereas prominent apraxia and asymmetric rigidity are features of corticobasal syndrome. Those with multisystem atrophy, however, rarely develop more severe dementia. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated dementia also has a subcortical pattern, often with marked slowing of information processing and motor clumsiness. Gait dyspraxia should suggest hydrocephalus, particularly if there is early urinary incontinence.

- Genetics: Although the vast majority of dementia in younger people occurs sporadically, some cases are due to gene mutations. This may be suggested by the atypical nature of the symptoms such as chorea in Huntington’s disease (HD), or a very early age of onset. Sometimes, MRI scan appearances may suggest a genetic aetiology with marked typical white matter abnormalities occurring in cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) and leukodystrophies. However, occasionally, typical clinical presentations such as AD occurring in late middle age can be due to dominantly inherited mutations, usually in the presenilin 1 (PS1) or less commonly amyloid precursor protein (APP) genes. Conversely, very early-onset FTD, in the absence of a family history, is rarely found to be due to a mutation. It is therefore important to take a careful family history, including first- and second-degree relatives, in all cases of dementia occurring in younger people.

Table 9.3 Progressive aphasias.

| Semantic | Non-fluent | Logopenic | |

| Clinical features | Fluent speechAnomiaImpaired single-word comprehensionSurface dyslexiaSpared repetition | Effortful, agrammatic speechApraxia of speechImpaired syntactical comprehension Preserved object knowledge | Slow speechWord finding pausesImpaired sentence repetition and comprehensionReduced word spanPreserved object knowledge |

| Imaging abnormalities | Left anterior temporal | Left posterior frontal and insular | Left posterior temporal and inferior parietal lobule |

| Pathology | TDP-43 | Tauopathy | AD type |

Gorno-tempini et al. (2011). Reproduced by permisison of Wolters Kluwer Health.

Patients with rapidly progressive dementia require urgent neurological investigation as do those with early myoclonus or seizures, as the aetiology is often non-neurodegenerative. Whilst conditions like Creutzfeldt–Jakob (CJD) continue to have a very poor prognosis, others such as some forms of limbic encephalopathy, which may also have prominent psychiatric symptomatology, respond well to immunological therapy.

Pharmacological treatment

Whilst younger people with AD can be treated in much the same way as older people with the same disorder, perhaps with less risk, the findings from AD studies cannot simply be applied to other diagnoses. Patients with FTD do not respond to cholinesterase inhibitors, which indeed may worsen their symptoms. They are particularly sensitive to the side effects of antipsychotic drugs but some aspects of their behaviour may benefit from treatment with trazodone.

Comprehensive assessment and support

Accurate diagnosis alone is insufficient. Younger people with dementia, their families and supporters require a comprehensive, multidisciplinary review of their needs followed by an individualised, age-appropriate care plan. These needs are seldom adequately met by conventional social care services, which are designed for frail older people. In particular, day care, respite and residential facilities for the elderly tend to be ill suited to the needs of younger people. Direct Payments, used to fund personalised support, is a good, flexible method of overcoming some of these limitations.

Information needs

Younger people with dementia and their families frequently report a lack of adequate information and counselling, particularly around the time of diagnosis. Information about the diagnosis and its implications in terms of treatment and prognosis must be given in a timely, user-friendly and sensitive format. Whilst information on AD abounds, it may be very difficult to access in an easily digestible form for some of the rarer conditions. Education programmes and telephone helplines can be useful sources of information.

Undergoing assessment for possible dementia is daunting, frightening and in some ways disadvantageous. Preassessment counselling is essential in enabling people to prepare for and give informed consent to an assessment.

Developing dementia at a young age is usually financially disastrous for the individual and the family. This situation is compounded by the complex nature of the benefits system. Impartial advice and information provided by a specialist social worker or benefits advisor can be invaluable.

Social needs

The majority of younger people with dementia are in paid employment at the time of onset and, indeed, occupational dysfunction is a common presenting feature of dementia in younger people. Risk assessment is of pivotal importance and may require a workplace occupational therapy assessment. It is not unusual for younger people with dementia to be made redundant or be dismissed from work. Employers should be encouraged to recognise dementia as a reason for early retirement so that pension rights and other benefits are not affected. Furthermore, some younger people with dementia wish to remain in employment, and efforts should be made to encourage employers to make reasonable workplace adjustments to accommodate disabilities and maximise strengths. It is quite common for younger people with dementia to be drivers. Where doubt remains about driving ability, particularly in atypical presentations, referral to a Regional Driving Assessment Centre will usually provide clarity.

Carer and family needs

Caring for a younger person with dementia is a major source of stress and burden, both known important risk factors for institutionalisation. Approximately one-half of carers of younger people with dementia have psychiatric morbidity, usually anxiety or depression. Carers have a legal right to have their own needs assessed, but it is also important to recognise and meet the needs of the wider family. Children and adolescents, who may also be carers, are also adversely affected and can sometimes require help from children’s services. Timely input from an experienced specialist community mental health or Admiral Nurse is particularly valued by families, especially when this support can be provided throughout the illness. Marked disruption in family dynamics, however, may require specialised input from family therapy services. Family members frequently overestimate their risk of inheriting dementia and can be reassured by accurate information. Additional complications, however, do arise for families when an inherited disorder is suspected, requiring liaison with genetic services and the provision of counselling and possible genetic testing.

Physical needs

Some forms of early-onset dementia are associated with an increased risk of choking, either as a result of abnormal eating behaviour or neurological dysfunction. Here, assessment by a speech and language therapist is an important part of the risk assessment. They will also be able to advise on management of dysphasia, which can be a major frustration to both patient and carer, increasing the risk of behavioural disturbance. Falls are particularly problematic in conditions such as HD and PSP, requiring input from physiotherapy. Dietary advice is important in conditions resulting in excessive weight loss (HD) or gain (FTD).

Service development

For successful, sustained service development, specific commissioning arrangements based on local need are required, with individuals identified at both a purchaser and provider level with responsibility for the service. There must be strong clinical leadership from well-motivated, experienced, specialists with dedicated clinical time. For populations of 500,000 and above, a dedicated multidisciplinary team is justified. Younger people and their families should be involved as partners in service development, and there must also be close collaboration with other services, with clear but flexible demarcation of responsibilities. Initial development should concentrate on diagnosis and community-based support.

Institutionalisation risk appears disproportionately high in younger people with dementia, with up to 30% residing in some form of care. It has been estimated that approximately 15 residential, nursing or long-stay places are required for every 100,000 people at risk (Harvey et al., 2003). Although institutional care can be delayed and sometimes avoided by good community care, specialist long-stay provision remains essential, because younger, physically robust patients with dementia generally do not mix well with their frail, older counterparts. Psychiatric admission is best avoided, as the needs of younger people with dementia cannot usually be adequately met on either older adult or general-adult wards.