and Aditya G. Shivane1

(1)

Cellular and Anatomical Pathology Level 4, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK

Abstract

Demyelinating diseases are characterised by the loss of myelin with relative axonal preservation, and affect both the central and peripheral nervous systems. The most common primary demyelinating disease of the central nervous system is multiple sclerosis, which can be classified into different clinical and pathological subtypes. The pathology of the other demyelinating diseases affecting the central nervous system, including Devic’s disease, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and acute haemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy, is also described. The pathology of trigeminal neuralgia is briefly discussed as it involves demyelination of the nerve root.

Keywords

DemyelinationPlaquesMultiple sclerosisRemyelinationDemyelinating disorders are characterised pathologically by loss of myelin with relative preservation of axons. They may affect either the peripheral or central nervous system (CNS), and in a few conditions e.g. adrenoleukodystrophies, affect both. Disorders affecting the peripheral nerves are discussed in Chap. 10. In addition to ‘primary’ demyelinating disorders, demyelination may be caused by infectious, metabolic and toxic factors and each of these will be discussed in their relevant chapters. This chapter will focus on primary demyelinating disorders affecting the CNS, but not include disorders of failure to produce myelin such as the leukodystrophies, which are covered in Chap. 14.

7.1 Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is by far the commonest demyelinating disorder of the CNS, affecting both the brain and spinal cord, usually presenting in young adulthood and is more frequent in women than men. There are a wide variety of clinical features including upper motor neuron weakness, paraesthesia, proprioceptive loss, cerebellar signs, vertigo, diplopia and vomiting. The disease is often preceded by an episode of optic neuritis and may also result in bladder and bowel disturbance, trigeminal neuralgia and cognitive impairment. Useful abnormal investigations which support the diagnosis include oligoclonal bands of IgG within the CSF, delayed visual evoked responses and enhancing areas of the white matter on magnetic resonance imaging of the CNS.

The aetiology of MS is likely to include a combination of environmental and genetic factors. The prevalence of MS varies geographically and is more common in populations living at a distance from the equator, possibly related to lower vitamin D levels, and some clusters of cases have suggested that an infective agent may be involved. MS has an increased incidence in relatives of patients with the disorder, and a number of genetic risk factors have been identified including HLA subtypes, signal transduction genes and genes involved in vitamin D metabolism.

The clinical course of multiple sclerosis is highly variable but could be broadly classified into different groups (Table 7.1).

Relapsing remitting MS | Episodes of well-defined relapse with partial or full recovery and periods between relapse where there is a lack of disease progression. |

Secondary progressive MS | An initial phase of relapsing remitting disease, followed by slowly progressive disease with few relapses, remissions or plateaus. |

Primary progressive MS | Progressive disease from onset, with only occasional plateaus or improvements. |

Clinically isolated syndrome | First clinical presentation of inflammatory demyelination, without criteria of dissemination |

Benign MS | Patient fully functional 15 years after disease onset. |

Malignant MS | Disease with rapidly progressive course leading to significant disability or death in a relatively short time from onset. |

Pathologically, MS can be divided into three subtypes; classic MS (Charcot type), acute MS (Marburg type) and concentric sclerosis (Balo’s disease).

7.1.1 Classic Multiple Sclerosis

This is by far the most common pathological pattern and results in well demarcated areas of demyelination, commonly known as ‘plaques’, which usually appear grey in colour to the naked eye, although acute lesions may appear yellow due to the presence of lipid derived from myelin breakdown. Plaques are usually bilateral, but asymmetric, and may extend to the surface of the CNS in the brain stem and spinal cord, and also be visible in the olfactory tracts and optic nerves. They are particularly common at the angles of the lateral ventricles (Figs. 7.1 and 7.2), but it is the brain stem and spinal cord lesions that cause the most problematic symptoms.

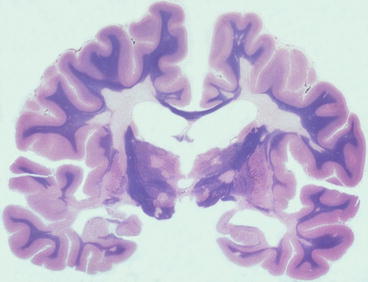

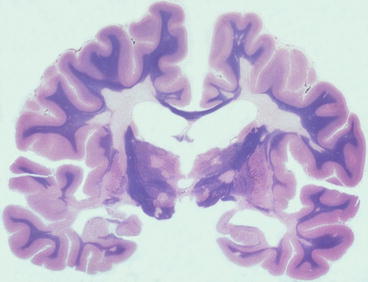

Fig. 7.1

Whole mount section of brain showing well demarcated areas of myelin loss, including at the angles of the lateral ventricles. Myelin stain

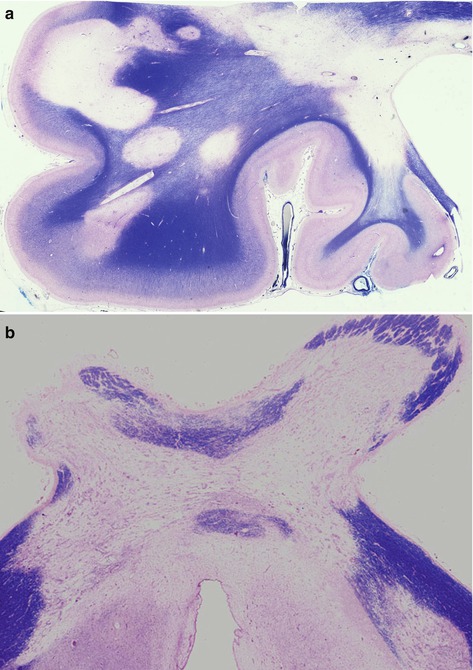

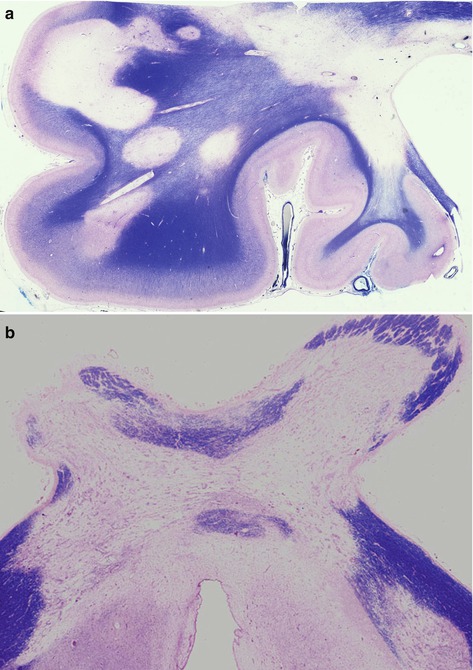

Fig. 7.2

(a) Chronic plaques in frontal lobe and, (b) optic chiasm showing well demarcated areas lacking myelin. Myelin stain

It is now recognised that extensive disease also occurs in the grey matter. Until relatively recently imaging and histological techniques were not sufficiently sensitive to demonstrate grey matter lesions, however, grey matter disease is present in almost all cases, often extensive, probably occurring early in the disease, and may be the pathological substrate for epilepsy and cognitive impairment [2].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree