OBJECTIVES

INTRODUCTION

The preservation of complete natural dentition is critical at all ages. In children, the prevention of early cavities is not only important for the healthy development of permanent teeth but also contributes to overall development and quality of life. The loss of teeth can bring negative social stigma, especially when tooth loss occurs at a young age. In addition to the social isolation and psychological pain that these problems can bring, general health may suffer as well.

People with poor dental health may have increased difficulty speaking, chewing, and swallowing, and in extreme cases, nutrition may be compromised. In patients with partial or complete dentures, chewing is difficult and in no way compares with natural dentition. Poor dentition also may lead to recurrent systemic infections such as pneumonia or endocarditis. Other conditions, such as worsening diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and preterm birth, may be exacerbated or increased by poor dental health (Box 41-1).

Box 41-1. Major Findings of the Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health

Oral diseases and disorders in and of themselves affect health and well-being throughout life.

Safe and effective measures exist to prevent the most common dental diseases, dental caries, and periodontal diseases.

Lifestyle behaviors that affect general health, such as tobacco use, excessive alcohol use, and poor dietary choices, affect oral and craniofacial health as well.

There are profound and consequential oral health disparities within the US population.

More information is needed to improve America’s oral health and eliminate health disparities.

The mouth reflects general health and well-being.

Oral diseases and conditions are associated with other health problems.

Scientific research is key to further reduction in the burden of diseases and disorders that affect the face, mouth, and teeth.

Source: From US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 2000.

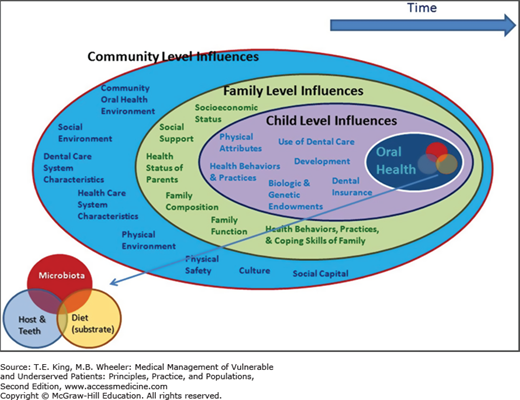

Factors influencing an individual’s oral health begin before birth, with the oral and overall health of the mother; these influences persist throughout childhood and into adulthood. Thus, when assessing risk, one must consider the health of the child within the context of individual, family, and community influences (Figure 41-1). We all have intrinsic characteristics, but children are greatly influenced by the families into which they were born. These families exist within communities, which exert both positive and negative social norms and physical options. These communities also are impelled by state and national policies. For children particularly, the passage of time can have great impact on their disease (or health) state and their resources to deal with it. These influences are numerous, but can be grouped broadly into five key domains: genetic and biological factors, social environment, physical environment, health behaviors, and utilization of dental/medical care.1 Dental treatment strategies should reflect such factors. This chapter discusses the importance of dental health to general health throughout the lifespan, identifies risk factors associated with dental caries (cavities) and periodontal disease, and suggests methods of educating patients about oral health.

EPIDEMIOLOGY: WHO IS AT RISK?

Oral care is a vital part of providing comprehensive care to all patients. However, the relationship of oral health to the overall health of patients is often overlooked, and many nondental health-care providers do not incorporate dental health into their care. Many patients and providers have limited knowledge as to how to prevent dental illness, and most patients seek help only for acute dental problems.

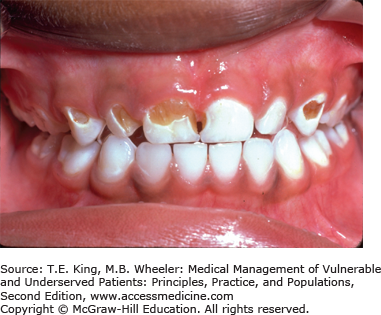

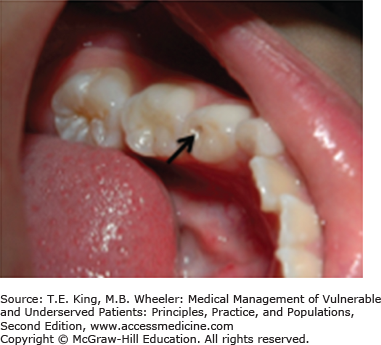

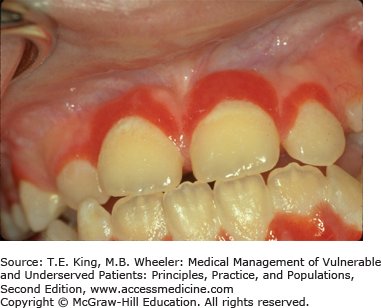

Factors such as age, economic status, limited access to dental care, low education and literacy, the existence of mental or physical handicaps, and ethnicity all contribute to risk for dental caries (Figure 41-2) and periodontal disease (Figure 41-3). In addition, chronic illnesses, poor nutritional and lifestyle habits, and a lack of dental knowledge put many patients at risk not only for the loss of teeth but also for the degradation of their overall health and quality of life. Consequently, what amounts to “a silent epidemic” of oral diseases is affecting the most vulnerable citizens: poor children, the elderly, those with disabling and chronic diseases, and many members of racial and ethnic minority groups.2

The prevalence of dental caries is widespread around the world and in the United States, and can be classified as a communicable disease.3 Tooth decay is the most chronic infectious, transmissible, and preventable childhood disease, with nearly 20% incidence of caries in children ages 2 to 4 years. In fact, in children, caries is five times more common than asthma and seven times more prevalent than hay fever.2 By the age of 17, nearly 80% of the US population has had a cavity or filling. More than two-thirds of adults between the ages of 35 and 44 have lost at least one permanent tooth.2 It is critical to prevent disease early in the primary dentition. Healthy baby teeth assist in the development of the permanent dentition, with implications for the proper placement of permanent teeth, speech, mastication of food and nourishment, self-esteem, and school readiness.

Juana is a 33-year-old immigrant from Mexico. She has no insurance and few economic resources. She took time off from her work as a nanny to come to the dental office. She speaks only Spanish, and says she seeks medical care only when something hurts.

Despite overall improvements in oral health status in the United States, profound disparities remain in some population groups as classified by sex, income, age, and race/ethnicity. Many people do not access dental care because of financial barriers. In fact, Juana’s practice of seeking dental care on an emergency-only basis has been shaped by her experience of inaccessibility, and is representative of many who live below the poverty line in the United States.

The prevalence of oral disease is significantly higher in those living below the federal poverty line. Poor children are twice as likely to have dental caries when compared with those from an affluent background. Moreover, they may exhibit behaviors that undermine oral health, such as increased juice consumption. The elderly population living in poverty is more likely to be edentulous.2 An individual’s environment, such as access to clean and optimally fluoridated drinking water, or fresh fruits and vegetables, also contributes to oral and overall health.

More than 108 million Americans lack dental insurance, 2.5 times more than those lacking medical insurance.2 Additionally, the likelihood of seeking dental care is 2.5 times greater in children with dental coverage than in those without it.2 Specific to Latinos, 76% of participants with dental insurance used services, compared with 47% of those without coverage.4 In a study of Latino immigrants in Southern California, nearly 70% had no dental insurance, and Latino children were the least likely to have dental insurance coverage.5

Low-income patients seeking dental care (often only when a patient is in pain) often seek the cheapest alternative for treatment. In the case of a toothache, this may be extraction, even though the tooth could be treated and maintained in the mouth by other therapeutic and more expensive treatment. In many states, access to dental care for low income is often limited to the dental safety net, hospital emergency rooms, dental or hygiene schools, free clinics, or public health/federally funded dental clinics. Often, these programs have a higher demand for dental services than can be supplied.6

Juana saw a dentist 5 weeks ago, but became frustrated in attempting to communicate with a non–Spanish-speaking provider. Since her last visit, she has had a swelling next to her lower right molar. She says the swelling comes and goes, as does the pain, but recently it has worsened. Although she knows she needs dental attention, she’s discouraged because of the language/cultural barrier.

Many minority patients have great difficulty accessing dental care. In addition to financial constraints, language barriers, fear of jeopardizing immigration status, and the lack of minority providers may be deterrent factors to seeking care.7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outlines profound oral health disparities in non-Hispanic blacks, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and Hispanics.8 Non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans, aged 35–44 years, are nearly twice as likely to experience untreated tooth decay as non-Hispanic whites.

The presence of dental disease is rampant among Hispanic youth. Many studies reveal that Latino children are at particular risk for early childhood caries (ECC). Of those living below the federal poverty line, Mexican-American children were significantly more likely to have untreated caries when compared with non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks. In those aged 2–4 and 6–8, Mexican Americans have the highest number of decayed and filled surfaces in primary dentition. In a study of young children near the California–Mexico border, 68% had ECC.9 The prevalence of ECC in Latino children is likely a result, at least in part, of a lack of dental education and awareness within Hispanic communities.

Juana has diabetes. A review of her medical history reveals a family history of diabetes and early tooth loss. Her mother was a diabetic and died at the age of 48. Juana complains that her molar on the lower right is loose and wants to have it pulled. This is the fourth tooth she has had extracted in the past year. Juana is not aware that her loss of her teeth is related to her uncontrolled diabetes and poor oral hygiene.

Positive association has been established between several illnesses and periodontal disease, a chronic inflammatory disease of the soft tissues and bone, with conditions including preterm low birth weight,10 hepatitis C, cardiovascular disease,11 stroke, and emphysema.12 A link between diseases that affect the immune system, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), and diabetes and periodontal disease has been well established.13,14

Observational studies have linked glycemic control in diabetics to the prevalence of periodontal disease. As diabetic control worsens, the likelihood of progressive periodontal disease increases. Current theory suggests a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease; control of periodontal disease helps control diabetes and vice versa.14 Health-care providers caring for diabetics must include dental care in their comprehensive care plans. Some have referred to the dental extractions commonly seen in diabetics as another kind of “amputation” that providers should seek to prevent.

Adults and children with medical disabilities, chronic illnesses, or those considered “special needs” with medically complex conditions or the frail elderly have significant issues in accessing care, including travel to a dentist’s office, appointment length, or difficulty finding oral health providers with special training and the physical setup necessary to treat a special needs patient. Similarly, individuals living in nursing facilities or chronic care homes may have limited options in accessing dental care. While some programs may arrange for in-house calls for oral health care, the scope of services may be limited and may or may not require patient financial obligation.

Quadriplegic patients and patients with physically impairing conditions such as Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke are likely to have more difficulty with brushing and flossing. Patients with severe mental disease are 3.4 times more likely than the general population to suffer loss of all their teeth.15 This is due, in part, to lack of proper oral self-care, and by side effects of psychotropic medications, such as dry mouth. The mentally impaired, such as those with Down syndrome and autism, may rely solely on their caretakers for oral care. In some cases, access to care is difficult because many dental offices are unequipped to manage patients with these physical and mental conditions. In some cases, these patients must be admitted to a hospital and placed under general anesthesia to administer care.

LIFE COURSE THEORY

The life course theory (LCT) is a conceptual framework that seeks to encompass patterns for health and disease among populations in the context of structural, social, and cultural influences.16 LCT places particular emphasis on the prenatal period, early childhood, and young adulthood as critical periods: times of “early programming.” For instance, the overall health, environmental exposures, and experiences of the mother prior to conception or delivery can result in the disease or susceptibility of the child. Here we discuss many of the specific oral health–related risks associated with various LCT stages.

Over the last two decades in the United States, there has been much attention to the oral disease status of the mother during pregnancy as a possible contributor to negative birth outcomes such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, spontaneous preterm birth, low birth weight, or even fetal loss.17,18,19 Boggess and colleagues summarize a two- to sevenfold increase in risk of adverse outcomes with concurrent active periodontal infection.20

Researchers at the University of North Carolina induced periodontitis in pregnant rodents21 and found that the maternal infection, resulting from the colonization of and destruction by gram-negative anaerobes, leads to maternal systemic response of elevated inflammatory markers (mainly prostaglandins, tumor necrosis factors, interleukins, and C-reactive protein) and, perhaps, even preterm birth.22,23 However, LCT challenges us to look even further downstream and determine how the child’s health and development trajectory, and perhaps increased susceptibility to oral diseases later in life, is affected by exposure to these negative conditions resulting from the mother’s periodontal infection.

Given the high incidence of chronic dental diseases, such as dental caries and periodontitis (a chronic inflammatory disease of the mouth), among US women of child-bearing age, it is critical to determine ways to minimize the negative impact on maternal and fetal responses to maternal periodontitis or gingivitis,24 and to delay or decrease the likelihood or severity of colonization by dental caries–causing bacteria passed from mother to child.

Many organizations have held consensus conferences and meetings to address possible interventions. Most recently, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recommended a dental screening at the first prenatal visit, to increase the likelihood of early intervention.25 The National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center,26 California Dental Association,27 State of New York,22 and other groups have identified interventions and oral health roles for dentists, obstetricians, allied health-care workers, and lay health workers to underscore the need for counseling pregnant women as early as possible about vertical transmission of caries and the maternal burden of disease from periodontitis. The importance of good oral health of both mother and their children is consistently outlined including breastfeeding, oral hygiene, and dental care utilization practices.

Infancy is generally a time of relative health, with great parental investment in preserving that health. Bottle feeding increases rates of Candida (thrush) in the mouth, and later of caries development, so providers and health-care systems should encourage breastfeeding by the mother. In addition, infants’ mouths are free of cariogenic bacteria, but this bacteria can be introduced when parents/caregivers with a high bacterial load prechew food, “clean” a pacifier in their mouth, or allow babies to stick their fingers in someone else’s mouth before putting them back in their own. To delay or halt colonization of cariogenic bacteria, start with wiping the gums and then brushing teeth after eruption can set an infant onto a more favorable health trajectory.

ECC, also known as baby bottle tooth decay, is defined as a condition of demineralization of the enamel with different degrees of cavitation in the primary dentition of children younger than 6 years.28 ECC, the most common chronic infectious disease in young children, is caused by bacteria, predominantly mutants, streptococci, and lactobacilli, which metabolize simple sugars to produce acid that demineralizes enamel, resulting in cavities. These bacteria are passed easily from mother to child, and consequently may develop as soon as teeth erupt.9

Children from ethnic minorities, those of low socioeconomic status or with limited access to dental services, are especially at risk for ECC (Figure 41-4). When left untreated, ECC can lead to pain and infection, as well as difficulty speaking, eating, and thus learning. Oral disease can have an impact on appetite and lead to depression and distractibility in school.29 These difficulties can have effects on cognitive development, school readiness, and self-esteem, increasing the child’s risk of school failure, while reducing the child’s quality of life. While ECC, by definition, is found only in children, its effects, including a dramatically increased risk of caries in the mixed and permanent dentition, often persist into adulthood. But despite its high prevalence, ECC is highly treatable and even preventable. The American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics both recommend that infant be seen by a dentist by age 1, or within 6 months of the eruption of the first tooth.30,31 However, the catchphrase “Two is too late!” has yet to be fully embraced by caregivers, and even by many dentists and pediatricians.

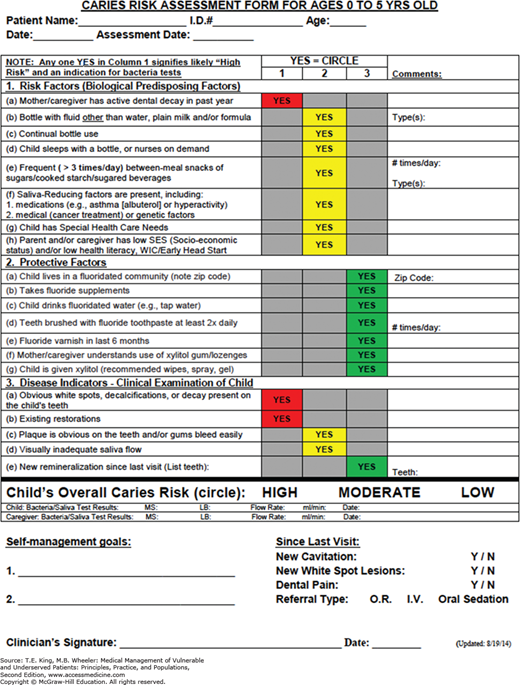

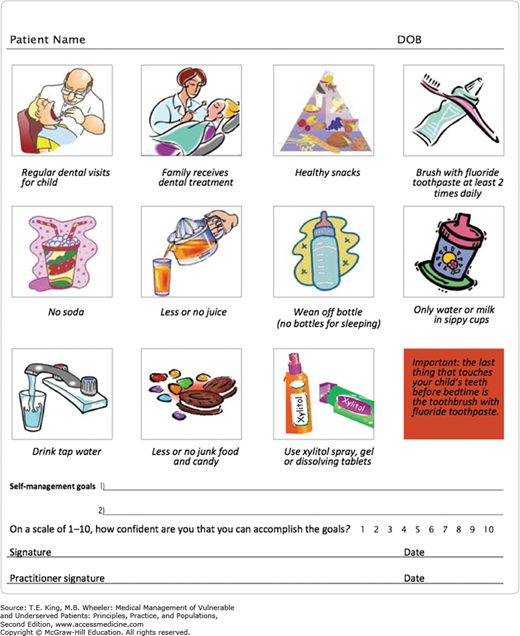

The key to good oral health in children is to begin early with preventive care and risk assessment.32 Consumption of limited amounts of fluoridated drinking water during infancy can help lay the foundation for healthy teeth. Once teeth have erupted, brushing with a small smear of fluoridated toothpaste twice per day and limiting the consumption of juices and sugary snacks help prevent ECC. At the child’s first dental visit, the oral health-care provider should complete a caries risk assessment, such as Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA),33 to determine risk level and help the child’s caregiver set self-management goals (Figures 41-5 and 41-6). For those infants determined to be at moderate or high risk of ECC, the provider may elect to apply fluoride varnish.

There are, however, several obstacles to obtaining early, preventive dental care for infants and young children. Many dentists in the United States do not accept patients younger than age 3, and a large proportion of pediatricians do not incorporate oral health evaluations or counseling into their practices. Even when pediatric dentists are available, many do not accept government-based dental insurance such as Medicaid, a fact that prevents many at-risk children from obtaining care. Perhaps one of the biggest issues is the “drill and fill” nature of many dental practices, where surgical interventions are the norm, and preventive care is deemed financially impractical, as insurance reimbursement rates are much higher for repairs after oral disease has already taken hold, than for early and regular case management aimed at preventing ECC.

Adolescence is a time of great developmental change. That includes a worsening of nutritional and self-care habits, and an increase in high-risk behaviors, including increased risk of trauma and exposure to negative substances such as alcohol, tobacco, or other illicit drugs. Moreover, adolescents are less likely to seek routine preventive care. Box 41-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree