Dental Sleep Medicine: Oral Appliance Therapy and Titration Management

Shawn Kimbro

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

1. Describe the role of the dentist in a comprehensive sleep disorders treatment plan.

2. Describe oral appliance therapy.

3. Identify different types of oral devices and their advantages and drawbacks.

4. Describe the role of the sleep technologist in oral appliance titration and therapy.

KEY TERMS

American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine

Dental device

Maxillomandibular advancement

Obstructive sleep apnea

Oral appliance therapy

Oral surgery

Sleep-disordered breathing

Management of sleep disorders requires a multidisciplinary approach and diverse perspectives. The role of the dentist has emerged as a key aspect in the care of patients with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). The recognition and treatment of sleep apnea may be more successful, both in efficacy and in compliance, if dentists and sleep specialists collaborate closely. This includes active participation by sleep technologists who are well-versed in aspects of SDB treatments and management. As practitioners in the health care field, dentists assist patients who are identified with SDB by making recommendations and referrals and by participating in treatment and overall management of the disease. This may include the use of oral appliance therapy (OAT), head and neck surgery, or upper airway surgery.

ORAL APPLIANCE THERAPY

As research into effective therapy options for treating SDB increases, there is growing interest in OAT. Oral appliances, sometimes called “dental devices,” are a simple and cost-effective method of treating snoring and mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Snoring is a symptom of OSA and an indication of increased upper airway resistance. The pharyngeal portion of the upper airway, from the soft palate to the base of the tongue, is where snoring and OSA typically occur. During sleep, activity in the upper airway dilator muscles decreases, causing the pharyngeal airway to shrink and sometimes close. Treatments for snoring or OSA aim to maintain upper airway patency during sleep.

The gold standard for treating SDB is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Many patients, however, are unable or unwilling to tolerate CPAP, so other options become necessary. Because oral appliances are portable and cost-effective, they are generally well accepted by patients either as an alternative to CPAP or as a first-line therapy. The appliances are worn in the mouth, similar to orthodontic devices or sports mouth protectors, during sleep to help stabilize the upper airway and promote improved breathing. An oral appliance helps maintain an open and unobstructed airway during sleep by protruding and stabilizing the tongue and mandible.

History

Oral appliances were considered for the treatment of upper airway obstruction as early as 1903 (1). In 1934, Pierre Robin described a functional appliance to move the mandible forward and alleviate tongue obstruction. By the early 1980s, research into SDB found that the vast majority of SDB cases are related to obstruction in the airway. Treatments introduced during this time included the surgical treatment uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (2) and nasal CPAP (3). Some early types of oral appliances were introduced, but they did not come into general use until the 1980s.

In the 1990s, research continued to show the efficacy of OAT in the treatment of SDB. As comparative data became available, physicians became more acceptive of oral devices. In 1991, a group of dentists who were interested in promoting the use of oral appliances as a part of sleep disorders therapy formed the Sleep Disorders Dental Society (now the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine [AADSM]). The AADSM’s mission also includes the promotion and coordination of research activities and recommendations for the implementation of OAT (4). In 1995, the American Sleep Disorders Association (now the American Academy of Sleep Medicine [AASM]) published a review indicating that oral devices presented an acceptable alternative to CPAP in the cases of simple snoring or mild-to-moderate OSA (5).

Recognizing the need for increased teamwork between physicians and dentists in order to achieve optimal treatment for patients with OSA, the AASM and the AADSM issued the first official joint clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with OAT in 2015 (6). The guidelines note that although positive airway pressure remains the gold standard for the treatment of OSA, the board-certified sleep medicine physician should take the patient’s preference into consideration. The guidelines further state that after a sleep physician prescribes OAT, treatment should be provided by a qualified dentist using a customized, titratable device and that efficacy should be confirmed or denied by follow-up sleep testing.

In order to assist technologists that are increasingly encountering oral appliances in the sleep center, the American Association of Sleep Technologists (AAST) released technical guidelines for oral appliance titration in 2018 (7). The guidelines recognize that the patient should be referred back to the sleep center to assess efficacy and that, during the overnight study, the technologist should work with the patient to titrate the oral appliance with the goal of identifying an optimal therapeutic setting.

Types of Oral Devices

Dentists use OAT for many purposes, but there are three primary types used for the treatment of SDB: tongue-retaining devices (TRDs), nonadjustable mandibular repositioning devices, and titratable mandibular repositioning devices.

Tongue-Retaining Devices

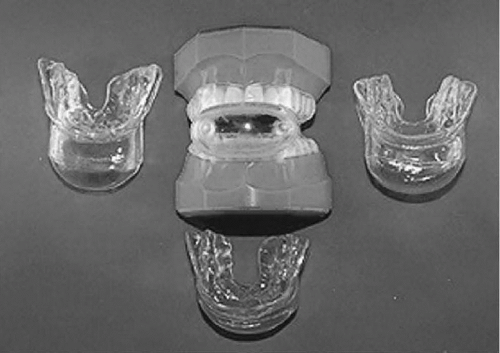

TRDs are placed between the upper and lower teeth and usually employ a suction cup or flange to move the tongue away from the back of the throat (Fig. 52-1). Some of these devices contain a bulb in which the tongue is inserted. The resulting repositioning keeps the airway clear from any obstruction caused by the base of the tongue. TRDs can work for patients with large tongues and for those who have few or no teeth. They are also used for patients who cannot adequately advance their mandible. Some TRDs are custom-fitted to the patient’s

teeth by use of dental impressions (Fig. 52-2). TRDs are not used frequently because they can cause an excessive buildup of saliva, difficulty swallowing, irritation of the tongue, and an increased gag reflex.

teeth by use of dental impressions (Fig. 52-2). TRDs are not used frequently because they can cause an excessive buildup of saliva, difficulty swallowing, irritation of the tongue, and an increased gag reflex.

Mandibular Advancement Devices

Mandibular advancement devices (MADs) are the most commonly used type of oral appliance to treat snoring and OSA. They can be classified into two main categories: nonadjustable (nontitratable) and adjustable (titratable). These devices fit over both the top and bottom teeth and work by repositioning the lower jaw both open and forward (see Fig. 52-1B). MADs are usually more effective in treating OSA than TRDs (8). When the mandible is advanced, the tongue and some soft tissue in the throat move forward to widen the airway space and reduce the likelihood of collapse. Air passes more freely through the airway, reducing snoring and sleep apnea. There are several different kinds of MADs (Fig. 52-3). Most use traditional dental techniques to attach the device to the patient’s teeth. Because it is extremely important that the devices fit precisely over the teeth, most MADs require dental impressions and fabrication by a dental laboratory. Because these devices have the potential to cause loss of dental restorations, facial discomfort, and bite changes, participation by a qualified dentist is imperative.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree