Depressive disorder – management

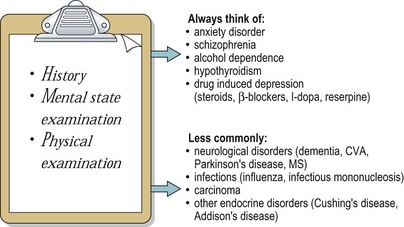

The differential diagnosis of depressive episodes is shown in Figure 1. Physical causes of depression need to be excluded, through physical examination and, if indicated, physical investigations, such as blood tests and neuroimaging. Blood tests, particularly full blood count and liver function tests, are important if covert alcohol dependence is suspected. Except in severe cases, people with depression usually give a good description of their symptoms but it is still helpful to talk to informants, whose account will not be affected by the negative thinking that is typical of depressive episodes.

Treatment

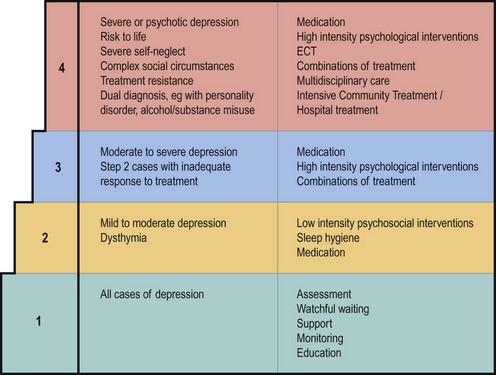

Treatment for depression is currently delivered according to the stepped care model illustrated in Figure 2. In this model, all people with depression start at step 1 and most people with symptoms of mild to moderate severity will be managed at step 1 or 2, with the minority of cases that do not improve being referred on to step 3. People with moderate to severe depression should be referred immediately to step 3 or step 4, on the basis of the criteria shown in the figure.

Interventions at steps 1 and 2 are provided in primary care, and in many areas this is also the case for step 3. A typical arrangement is for a team of high intensity and low intensity mental health workers to be based at large GP surgeries, or across a cluster of smaller practices, with prescribing being carried out by GPs with advice from a psychiatrist when needed. Level 4 care is provided by mental health services, using the different methods of service delivery described on pages 2–5. Psychiatrists will take a lead in prescribing at level 4 and there will be access to more specialised or intensive psychological treatments.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree