- If available, a reliable sleep history is generally more useful than sleep investigations in diagnosing sleep disorders

- Cyclical dips in blood oxygen saturations overnight form the basis of diagnosing sleep apnoea syndromes and can be demonstrated by simple home oximetry tests in most cases

- Sophisticated home ambulatory recording equipment can be used to confirm sleep apnoea if there is diagnostic doubt

- Full overnight polysomnography provides a clear objective snapshot of a subject’s sleep quality but always needs to be analysed in a clinical or symptom-based context

- Accurately measuring objective levels of sleepiness and wakefulness is very difficult, partly due to uncertainties over the normal range

- The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) and maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT) are considered ‘gold standards’ for measuring or quantifying levels of sleepiness but are very sensitive to procedural variations and protocols

- Actigraphy is a simple technique that gives a useful approximation of a subject’s sleep–wake cycle over a period of weeks by continuously measuring limb movements

Largely due to the perceived mysterious nature of sleep and the difficulties in investigating it, many clinicians lack confidence when diagnosing sleep disorders. This partly reflects the wide spectrum between normal and abnormal but also reflects the relatively low profile of sleep medicine in most educational curricula.

The most widely accepted international classification of sleep disorders (ICSD) was last revised in 2005 and outlines eight major categories (Box 2.1). Although a useful and exhaustive guide, it is written from a largely American perspective that it not always applicable or appropriate to clinical practice in other countries. Furthermore, it is clear that the relatively new field of sleep medicine continues to evolve rapidly and that many uncertainties and ambiguities remain.

A common misperception amongst non-specialists is that sophisticated investigative techniques are invariably needed for accurately diagnosing sleep disorders. However, a directed and reliable sleep history is almost invariably more useful than sleep tests (Table 2.1). Clearly, difficulties may arise if helpful or essential collaborative information from a bed partner or family member is not available. A self-completed sleep diary for at least two weeks can be a useful addition to history taking (Figure 5.2 shows an example).

Table 2.1 Some important sleep-related symptoms and their implications.

| Sleep-related symptom | Implications |

| Short sleep time (<6 hours) | Short sleeper (constitutional); all types of insomnia; consider depression; circadian rhythm disorder (especially delayed sleep phase syndrome [DSPS]) |

| Irregular sleep times | Social or work related; circadian rhythm disorder |

| Delay in falling asleep | Sleep-onset insomnia, look for secondary cause(s) |

| Difficulty waking in morning | Sleep deprivation; sleep inertia (sleep ‘drunkenness’); idiopathic hypersomnolence |

| Restless during night | Frequent arousals (look for causes of secondary sleep-maintenance insomnia); obstructive sleep apnoea; periodic limb movements during sleep; rarely epileptic phenomena |

| Complex movements during sleep | Parasomnias; nocturnal epilepsy may need to be considered |

| Snoring | Simple or primary snoring with no adverse consequences to the subject; upper airway resistance syndrome; obstructive sleep apnoea |

| Nocturnal choking | Obstructive sleep apnoea; gastro-oesophageal reflux; vocal cord adduction causing stridor; panic attacks |

| Unrefreshing sleep | Sleep restriction; all causes of secondary sleep-maintenance insomnia, including conditions associated with hyper-arousal such as fibromyalgia |

| Daily early morning headache | Carbon dioxide retention; obstructive sleep apnoea |

| Daytime naps | Insufficient sleep; all causes of secondary insomnia; narcolepsy; idiopathic hypersomnia |

| Weakness, localised or general, with emotion | Cataplexy, invariably in association with narcolepsy |

| Pre-sleep apprehension | Anxiety; psychophysiological insomnia; fear of event during sleep (nightmares, parasomnias) |

| Pre-sleep leg discomfort and movements | Restless legs syndrome and associated periodic limb movements |

This chapter will focus on diagnostic investigations used to confirm clinically suspected sleep disorders. It should be emphasised that information from sleep testing is not always diagnostic in itself and invariably needs to be taken in context with a patient’s sleep–wake symptoms of concern. It is not rare for minor abnormalities picked up on sleep tests to be misleading or misinterpreted.

Tests for sleep-related breathing disorders

Before embarking on formal treatment for a sleep-related breathing disorder such as obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), it is mandatory to provide some objective evidence to confirm the diagnosis.

Many clinics specialising in sleep apnoea will only accept patients for a diagnostic work-up if there are associated indications of daytime hypersomnolence. The most commonly accepted simple screen for assessing levels of somnolence is the Epworth scale. In this subjective assessment, a subject has to rate the chances of falling asleep (between 0 and 3) over the previous few weeks in eight routine situations (Box 2.2). A score of over 10/24 on the scale is often taken as the arbitrary criterion for accepting referrals to a sleep apnoea clinic.

- Sitting and reading

- Watching TV

- Sitting inactive in a public place (e.g. theatre or meeting)

- Sitting as a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

- Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit

- Sitting and talking to someone

- Sitting quietly after lunch without alcohol

- Sitting in a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic

| Patient rates each item as | 0 (would never doze) to 3 (high chance of dozing) |

| ESS total score: | 0 → 24 |

ESS = Epworth sleep scale

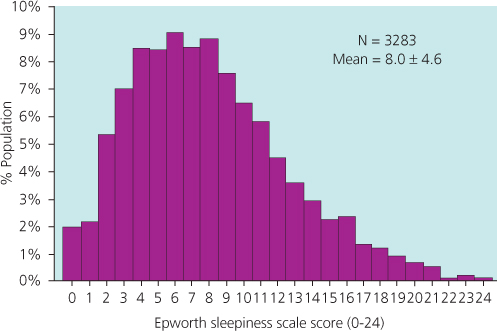

The Epworth scale is easy to administer but highly subjective, with a significant range of normality in the general population (Figure 2.1). Furthermore, some of the questions may not be valid or appropriate for certain individuals, including children.

Figure 2.1 Daytime sleepiness in a population-based sample. In this representative sample of the general population, almost 20% scored 11 or over on the Epworth scale, indicating possible excessive daytime sleepiness. Severe OSA patients or those with narcolepsy would be expected to score 15 or over.

Oximetry

Ambulatory oximetry is a simple and inexpensive screening tool for OSA that can be undertaken in a subject’s home. A finger probe measures oxyhaemoglobin saturation during the recording period of one or more nights along with pulse rate (Figure 2.2). In clear cut cases of sleep apnoea, a characteristic pattern of saturation dips with associated pulse rises is seen (Figure 2.3a and 2.3b). A desaturation index of significant oxygen dips per hour measuring more than 4% is often taken as a useful guide of OSA severity.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>