(1)

Cognitive Function Clinic, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, UK

7.1.1 Memory: Amnesia

7.1.3 Perception: Agnosia

7.1.4 Praxis: Apraxia

7.2 Comorbidites

7.2.2 Delirium

7.2.3 Epilepsy

7.2.4 Sleep-Related Disorders

7.2.5 Diabetes Mellitus

7.3 No Diagnosis

Abstract

This chapter examines the various cognitive syndromes (e.g. amnesia, aphasia, agnosia) which may be defined by clinical assessment and investigation, as a prelude to establishing aetiological diagnosis. It also examines various comorbidities which may be encountered in dementia disorders, including behavioural and neuropsychiatric features, delirium, epilepsy and sleep-related disorders.

Keywords

DementiaDiagnosisCognitive syndromesComorbidities7.1 Cognitive Syndromes

The diagnosis of specific dementia disorders (see Chap. 8) may be facilitated by the definition of cognitive syndromes. In other words, diagnosis of a clinical syndrome may inform the aetiological diagnosis, although the mapping is far from 1:1 because of the heterogeneity of pathological entities, with clinical phenotype depending on the exact topographic distribution of disease.

Cognitive neuropsychology often depends on unusual cases with highly circumscribed deficits for the development of ideas about brain structure/behaviour functional correlations (Shallice 1988). The messy contingencies of clinical practice seldom correspond to these archetypal cases, but nonetheless specific cognitive syndromes can often be delineated, which facilitates differential diagnosis. The classical deficits, corresponding to the recognised domains of cognitive function examined by cognitive screening instruments (see Chap. 4), are amnesia, aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and a dysexecutive syndrome. In turn, specific clinical diagnoses (see Chap. 8) may be arrived at based on these deficits and informed by investigation findings (see Chap. 6).

7.1.1 Memory: Amnesia

Amnesia is an acquired syndrome of impaired encoding of information resulting in impaired recall. Amnesic syndromes may be classified according to variables such as onset (acute, subacute, chronic), duration (transient, persistent), and course (fixed, progressive) (Fisher 2002; Papanicolaou 2006; Larner 2011a:24–6). Many causes of amnesia are recognised (Box 7.1), some of which have been encountered in CFC.

Box 7.1: Causes of Amnesia

Chronic/persistent:

Alzheimer’s disease

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

Sequela of herpes simplex encephalitis

Limbic encephalitis (paraneoplastic or non-paraneoplastic)

Hypoxic brain injury

Bilateral paramedian thalamic infarction/posterior cerebral artery occlusion (“strategic infarct dementia”)

Third ventricle tumour, cyst; fornix damage

Temporal lobectomy (bilateral; or unilateral with previous contralateral injury, usually birth asphyxia)

Focal retrograde amnesia (rare)

Acute/transient:

Closed head injury

Drugs

Transient global amnesia (TGA)

Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA)

Migraine

Hypoglycaemia

From the chronic/persistent group, an amnesic syndrome is the most common presentation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Larner 2006a, 2008a), often with evidence of mild dysfunction in other cognitive domains (e.g. perception, language, executive function), but sometimes occurring in isolation. Likewise mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may be exclusively amnestic (single-domain amnestic MCI) or show deficits in other domains (multi-domain amnestic MCI; Winblad et al. 2004). A temporal gradient is often evident in the amnesia of AD, with more distant events being more easily remembered than recent happenings, often characterised by relatives as a defect in “short term memory” with preserved “long term memory”. Verbal repetition (“repetitive questioning”) regarding day to day matters, reflecting the amnesia, is one of the most common and, for relatives, most troubling symptoms of AD (Rockwood et al. 2007; Cook et al. 2009).

All the cognitive screening instruments used in patient assessment have memory testing paradigms, usually of the registration/recall type, sometimes with an added recognition paradigm, and specific cognitive tests for memory are also available (e.g. Buschke et al. 1999). The hippocampal origin of the AD/amnestic MCI memory deficit may be examined by controlling for the encoding phase (e.g. the “5 words” test of Dubois et al. 2002). This may also help in the differentiation from physiological age-related memory complaints, the growing difficulty in encoding new information which afflicts us all as we age.

Memory complaints may be evident in neurodegenerative disorders other than AD, but often accompanied by other more prominent symptoms which assist in differential diagnosis. Although a complaint of memory difficulties is not infrequent from relatives of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) syndromes, this is more often related to behavioural and linguistic problems rather than amnesia per se, although amnesic presentations of pathologically confirmed FTLD have been described on occasion (e.g. Graham et al. 2005). Diagnostic errors confusing FTLD with AD may therefore occur (Davies and Larner 2009a), and some FTLD cases undoubtedly do have an AD-like phenotype (Doran et al. 2007; Larner 2008b, 2009). Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) may also be mistaken for AD, but typically there is more attentional disturbance and visuospatial dysfunction with relative preservation of memory.

Alcohol-related memory problems, both Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (described before Korsakoff by Lawson in 1878; Larner and Gardner-Thorpe 2012) and alcohol-related dementia, have been seen only rarely in CFC, presumably because local services for alcohol problems absorb these patients. This situation may change in the future if current concerns about binge drinking habits in youth translating into an epidemic of alcohol-related dementia come to pass (Gupta and Warner 2008).

Limbic encephalitis is a syndrome of subacute or chronic amnesia, often accompanied by anxiety and depression, epileptic seizures, hypersomnia, and hallucinations, with active CSF (pleocytosis, raised protein). The syndrome may be viral, paraneoplastic (particularly associated with small-cell lung cancer), or non-paraneoplastic in origin (Schott 2006; Tüzün and Dalmau 2007). Non-paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis with serum antibodies which were initially thought to be directed against voltage-gated potassium channels (VGKC-NPLE; Thieben et al. 2004; Vincent et al. 2004), but whose antigen was latterly shown to be LGI1 (Lai et al. 2010), has attracted particular attention, not least because of its potential amenability to treatment. A number of VGKC-NPLE patients have been reported from CFC (Wong et al. 2008, 2010a, b; Ahmad and Doran 2009; Ahmad et al. 2010). In a consecutive series, immunosuppressive therapy with plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulin, and intravenous followed by oral steroids was associated with prompt remission of epileptic seizures and correction of hyponatraemia (1 week), improvement in cognitive function as assessed with the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination and its revision (ACE and ACE-R; see Sects. 4.5 and 4.6) (3 months), and improvement in neuroradiological appearances (9 months) (Wong et al. 2008, 2010a, b). Some patients with VGKC-NPLE have been reported to develop a profound retrograde amnesia as a sequela of the acute disease (Chan et al. 2007), prompting speculation that some cases of “focal retrograde amnesia” (see below; Kapur 1993) may in fact be recovered episodes of VGKC-NPLE (Lozsadi et al. 2008). Hence, though rare, VGKC-NPLE must be considered in cases of subacute amnesia because of its potential reversibility. Limbic encephalitis associated with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) has also been seen in CFC (Bonello et al. 2014). Unlike VGKC-NPLE, this is a chronic non-remitting disorder, with antibody titres remaining high after immunosuppression, and patients continue to have seizures despite intense anti-epileptic drug therapy (Malter et al. 2010). Sequential cognitive assessment of one patient with the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS; Randolph et al. 1998; see Sect. 4.14) showed no evidence for cognitive improvement over 30 months of follow-up (Bonello et al. 2014).

From the group of acute/transient amnesias, probably the most commonly encountered condition is transient global amnesia (TGA). TGA consists of an abrupt attack of impaired anterograde memory, often manifest as repeated questioning, without clouding of consciousness or focal neurological signs (Bender 1956; Guyotat and Courjon 1956; Fisher and Adams 1964). Neuropsychological assessment during an attack shows dense anterograde amnesia, variably severe retrograde amnesia, but intact working memory and semantic memory. Implicit memory functions (e.g. for driving) are usually intact. Episodes are of brief duration (<24 h), with no recollection of the amnesic period following resolution. Aetiology is uncertain but thought likely to be vascular, possibly migrainous, causing temporary deactivation or functional ablation of memory-related neuroanatomical substrates (Sander and Sander 2005; Quinette et al. 2006; Bartsch and Deuschl 2010). A 4-year survey (2002–2005 inclusive) of CFC practice identified only ten cases in which the diagnosis of TGA was suspected, in only eight of which were suggested diagnostic criteria for TGA (Hodges and Warlow 1990) fulfilled. Of the eight definite cases, all were female (age range 48–71 years). Three were seen in outpatient clinics, five as ward consultations, and the majority (7, =88 %) in district general hospitals. Working or suggested diagnoses (sometimes more than one), available in seven cases at time of referral to the neurologist, were stroke or TIA (five cases), epilepsy (2), and viral illness (1) (Larner 2007a). The preponderance of female cases was confirmed when the survey was extended to 6 years (M:F = 1:10; Lim and Larner 2008a), 9 years (M:F = 5:11; Larner 2011b), and 12 years (M:F = 10:14; Milburn-McNulty and Larner 2014) but the falling ratio may indicate that this is simply a chance observation associated with the small number of cases seen. (A recent population-based cohort study found that females with migraine aged 40–60 had a greater risk of developing TGA: Lin et al. 2014.) Recognised precipitating factors for TGA, such as sexual activity (Larner 2008c), have been noted in only a minority of cases (Larner 2011b; Ung and Larner 2012). Occasional familial cases of TGA are observed (Davies and Larner 2012). One case of TGA possibly related to an underlying brain tumour, a rarely reported association, has been observed (Milburn-McNulty and Larner 2014).

Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA) is a distinctive epilepsy syndrome, characterised by brief amnesic episodes, typically occurring on waking, and associated with accelerated long-term forgetting and autobiographical amnesia. TEA enters the differential diagnosis of TGA, but differs in a number of respects, including the timing and frequency of attacks (Butler and Zeman 2011). Over the 12-year period 2002–2013 inclusive, only two possible cases of TEA have been encountered in CFC (vs. 24 cases of TGA), and only one of these was thought to be definite. In this case, episodes initially diagnosed as parasomnias but typical of TEA had approximately the same age at onset as a more pervasive memory problem which evolved to AD (Krishnan and Larner 2009). Epileptic seizures in AD may take a number of forms, and may occur at onset of cognitive decline (although they become more frequent with disease duration; see Sect. 7.2.3), so this concurrence might possibly reflect shared pathogenic processes involving synaptic network pathology in the medial temporal lobes (Larner 2010a, 2011c). TEA has also been suggested as a cause of wandering behaviours observed in AD patients (Rabinowicz et al. 2000).

Unusual causes of an amnesic syndrome which have been seen on occasion in CFC, and which may need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of amnesia, include profound hypoglycaemia (Larner et al. 2003a), migraine (Larner 2011d), multiple sclerosis (Larner and Young 2009), focal retrograde amnesia (Larner et al. 2004a), and damage to the fornix as a consequence of an isolated subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (Ibrahim et al. 2009).

Profound hypoglycaemia is a recognised cause of acute amnesia (Fisher 2002), but relatively few cases with longitudinal neuropsychological data have been reported (e.g. Chalmers et al. 1991). A patient seen in CFC (Case Study 7.1) illustrated a focal pattern of deficit, selective for anterograde memory and learning, probably reflecting hippocampal vulnerability to the effects of neuroglycopaenia, which may gradually, though incompletely, reverse over time (Larner et al. 2003a).

Case Study 7.1: Acute Amnesia: Hypoglycaemia

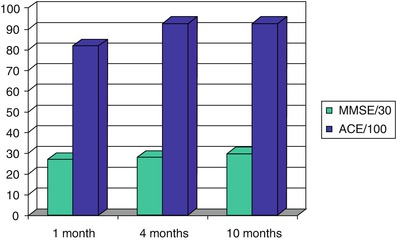

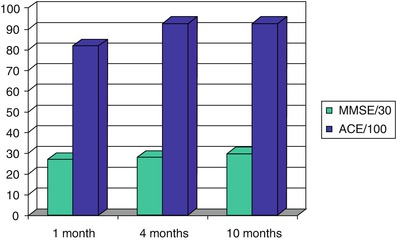

A 61-year old man with long-standing (ca. 50 years) insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type 1 which was being treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion was found collapsed with blood glucose of 1.0 mmol/l. After correction of hypoglycaemia, he noted difficulty remembering names of friends and content of recent conversations, necessitating use of external memory aids. Neuropsychological assessment showed normal attention, concentration, language and working memory function, but impaired verbal and visual immediate and delayed recall (WMS III, Camden Memory Tests). MRI brain scan was normal. There was gradual improvement in his memory function: at 4 months he continued to have impairments in short term verbal memory and learning but there was improvement in visual memory. Scores on MMSE at 1, 4 and 10 months were 27, 28, and 30/30, and on Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination were 82, 93, and 93/100 respectively (Fig. 7.1).

Figure 7.1

Progression of cognitive performance following an episode of profound hypoglycaemia (Larner et al. 2003a)

Amongst the many transient phenomena that may be encountered in the context of migraine attacks, amnesia is sometimes prominent. A patient who drove apparently safely for several miles, missing her turning, without awareness of her journey (“unconscious driving phenomenon”) developed a headache typical of migraine, which she had suffered from since teenage years, at the end of her journey (Larner 2011d). It is of note that memory impairment does not necessarily impair most aspects of driving performance, as shown by a study of two experienced drivers with bilateral hippocampal lesions causing severe amnesia (Anderson et al. 2007). There may be a relationship between migraine and TGA, some authors considering TGA to be a migraine aura (Lane and Davies 2006:125–30, 168). A syndrome of acute confusional migraine is recognised in children (Pacheva and Ivanov 2013) which has some features akin to TGA (Sheth et al. 1995; Schipper et al. 2012); both may be examples of “cognitive migraine” (Larner 2013a).

Although cognitive impairment is increasingly recognised as a clinical feature of multiple sclerosis (MS), this is usually of subcortical type with impaired executive function and slowed processing speed as a consequence of progressive acquisition of white matter damage (LaRocca 2011), whilst cortical cognitive syndromes are relatively rare: hence a typical “white matter dementia” (Filley 2012). Cognitive impairment can on occasion be a prominent early symptom of MS (Larner and Young 2009; Young et al. 2008). Prominent amnesia has been described in a cortical variant of MS, with or without aphasia, alexia and agraphia (Zarei et al. 2003), but acute presentation of MS with higher cognitive dysfunction such as amnesia (Vighetto et al. 1991) or aphasia (see Sect. 7.1.2; Larner and Lecky 2007) is unusual. Other potential causes for these syndromes occurring in MS should always be considered. One patient with an acute onset of demyelinating disease, probably relapsing-remitting MS, and with the clinical phenotype of amnesia has been encountered in CFC (Larner and Young 2009). The rarity of amnesia in MS may perhaps explain the relatively lack of efficacy of ChEI for cognitive impairment in MS (Larner 2010b:1701).

Focal retrograde amnesia is a rare syndrome in comparison with anterograde amnesia, in which recent events can be more easily recalled than distant ones, a reversal of the usual temporal gradient of amnesia (Kapur 1993). In one case of focal retrograde amnesia seen in CFC, the Autobiographical Memory Interview (Kopelman et al. 1989) showed autobiographical amnesia for childhood, teenage and adult life but the patient was able to give a reasonable account of current news events and auditory delayed recall was preserved. MR brain imaging showed some left temporal lobe atrophy (Larner et al. 2004a). The aetiology of focal retrograde amnesia is uncertain; in this case it may possibly have been related to prior alcohol misuse. Functional amnesias are typically retrograde in nature (Markowitsch and Staniloiu 2013).

Anterograde amnesia associated with damage to the fornix, a fibre bundle which connects the hippocampus to the mammillary bodies within the limbic system, has been described (Sweet et al. 1959), particularly following removal of third ventricle colloid cysts (Aggleton et al. 2000). Such cases indicate the importance of the fornix as one of the anatomical substrates of the distributed neural network underpinning memory functions (Mesulam 1990). A patient with persistent anterograde amnesia with some additional executive dysfunction following removal of an isolated subependymal giant cell astrocytoma which invaded the left fornix has been seen in CFC (Fig. 7.2; Ibrahim et al. 2009). Amnesia did show some improvement over a period of 12 months, suggesting that tissue swelling secondary to traumatic dissection may have contributed to the clinical presentation and course.

Figure 7.2

Preoperative CT brain scan showing a structural lesion involving left fornix. Patient developed post-operative amnesia. Histology showed a subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (Ibrahim et al. 2009)

7.1.2 Language: Aphasia, Alexia

Aphasia is an acquired syndrome of impaired language function affecting the spoken word. The symbolic code of language may also be impaired in the context of its written form, either in reading (alexia) or writing (agraphia), difficulties in which (e.g. fluency, comprehension) generally mirror those in the spoken form. Various causes of aphasia are recognised (Benson and Ardila 1996; Rohrer et al. 2008; Larner 2011a:35–7).

A linguistic presentation is one of the commonly recognised phenotypes of FTLD. This aphasia may be either non-fluent or fluent, the syndromes of progressive non-fluent aphasia and semantic dementia, respectively (Neary et al. 1998; McKhann et al. 2001), now denoted as the agrammatic and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia (Gorno-Tempini et al. 2011; see Sect. 8.2).

Aphasic presentations of Alzheimer’s disease are well-recognised (e.g. Mendez and Zander 1991; Galton et al. 2000; Caselli and Tariot 2010:91–9) but rare. Clinically these may sometimes have the phenotype of progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) or, much less commonly, semantic dementia (Davies et al. 2005; Alladi et al. 2007). Some authors also delineate a third type of progressive aphasia, logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA; Gorno-Tempini et al. 2004), characterized by slow speech with long pauses, impaired syntactic comprehension and anomia; AD pathology may be the most common neuropathological substrate of this syndrome (Gorno-Tempini et al. 2008) which has been conceptualised by some as a unihemispheric variant of AD. Aphasic presentations have accounted for around 4.5 % of new AD cases seen in CFC over a 6-year period (2000–2005) (Larner 2006a). Great care must be taken with this diagnosis, however, because of the possible confusion with linguistic presentations of FTLD; instances requiring diagnostic revision following the passage of time have been encountered (see Sect. 8.2; Davies and Larner 2009a).

Overlap between the linguistic features of PNFA and clinically diagnosed corticobasal degeneration has been noted (Graham et al. 2003) although the frequency of CBD phenocopies might possibly jeopardise this conclusion (Doran et al. 2003; Larner and Doran 2004).

Occasional unusual cases with linguistic presentations have been seen in CFC (Larner et al. 2004b; Larner 2005a, 2006b, 2012a; Larner and Lecky 2007). Acute aphasia is most often due to stroke in the territory of the dominant hemisphere middle cerebral artery. Occasional atypical, acute aphasic, presentations of neurodegenerative disease, both FTLD and AD, have been seen in CFC following cardiac surgery, and initially mistaken for cerebrovascular disease (Larner 2005a). Presumably, an acute cerebral insult may render manifest a previously slowly progressing subclinical neurodegenerative disorder (vide infra, for a similar presentation of Braille alexia; Larner 2007b). Cerebrovascular disease is recognised to lower the threshold for the clinical manifestation of underlying AD pathology (Snowdon et al. 1997).

Aphasia is a rare presentation in multiple sclerosis (Lacour et al. 2004), in contrast to dysarthria which is common. The possibility of a second pathology should be considered when a patient with established MS develops acute aphasia, for example cases of partial seizures or non-convulsive status epilepticus causing aphasia (“status aphasicus”) have been presented (e.g. Trinka et al. 2002). In a case of acute aphasia in a patient with long-standing MS seen in CFC, CT brain imaging showed a heterogeneous, partially calcified, lesion in the left lateral temporal lobe with an area of high density anterolaterally, suggesting an acute haemorrhage, confirmed on MR imaging, which also showed typical MS periventricular white matter changes. A second lesion returning heterogeneous signal was also observed in the left occipital lobe. These lesions were thought most likely to be cavernomas, hence entirely incidental to the MS (Larner and Lecky 2007).

Various causes of alexia are recognised (Larner 2011a:15–7; Leff and Starrfelt 2014). The classical disconnection syndrome of alexia without agraphia, also known as pure alexia or pure word blindness, is a form of peripheral alexia in which patients lose the ability to recognise written words quickly and easily. Although patients can write at normal speed, they are unable to read what they have just written. Some authorities classify this syndrome as a category-specific agnosia. Alexia without agraphia often coexists with a right homonymous hemianopia, a particular problem in a patient who passed through CFC (reported by Imtiaz et al. 2001) who sustained at least one accident because of his visual field defect.

Reading may be achieved through the tactile, as well as the visual, modality, as in Braille reading. The nineteenth century American physician Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894) in his Prelude to a volume printed in raised letters for the blind (1885) noted Braille readers to be:

… – you whose finger-tips

a meaning in these ridgy leaves can find

Where ours go stumbling, senseless, helpless, blind.

Alexia for Braille reading has rarely been reported (e.g. Birchmeier 1985; Signoret et al. 1987; Hamilton et al. 2000); an additional patient has been seen in CFC (Larner 2007b; Case Study 7.2).

Case Study 7.2: Acute Braille Alexia

A septuagenarian, blind from birth, a proficient Braille reader with her left index finger, found that she could not read following apparently uncomplicated coronary artery bypass graft surgery. On examination, her spoken language was fluent with no evidence of motor or sensory aphasia. There was no left-sided sensory neglect or extinction, and no finger agnosia. Testing stereognosis in the left hand, she was able to identify some objects (pen, ring, paper clip, watch) but was slow to identify a key, could not decide on the denomination of a coin (50 pence piece, heptagonal; or 10 pence piece, circular) and thought a £1 coin was a badge, although she identified this immediately with the right hand. Two-point discrimination was 3 mm on the pulp of the right index finger (minimum spacing possible between tines) but 5 mm on the pulp of the left index finger. MR imaging of the brain showed a few punctate high signal lesions on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences in subcortical white matter, thought to be ischaemic in origin, including one subjacent to the right motor cortex in the region of the internal watershed between anterior and middle cerebral artery territories.

Braille alexia may be viewed as the tactile homologue of pure alexia (alexia without agraphia), and may result from disruption of different, possibly overlapping, psychoperceptual mechanisms, some analogous to those postulated in pure alexia. It may reflect problems integrating tactile information over the temporal or spatial domains, hence an associative form of agnosia (Signoret et al. 1987; Fisher and Larner 2008). A frontal-parietal network may contribute to the integration of perception with action over time, and right hemisphere lesions may be associated with impaired integration of spatial information from multiple stimuli. Tactile agnosia (and astereognosis) may arise from lesions of the parietal area of the cerebral cortex (Luria 1980:168). Alternatively, Braille alexia may reflect a perceptual impairment, hence an apperceptive form of agnosia, as in this case (Larner 2007b). Since Braille characters are close to the limits of normal perceptual resolution, impaired light touch perception following damage to primary sensorimotor cortex or its connections may result in degraded tactile identification and slowed Braille reading speed.

7.1.3 Perception: Agnosia

Agnosia is a syndrome, most usually acquired, of impaired higher sensory function leading to a failure of recognition, occurring most often in the visual modality but also in other sensory domains (Farah 1995; Ghadiali 2004; Larner 2011a:9–10). As mentioned, Braille alexia may in fact be a form of tactile agnosia (see Sect. 7.1.2; Larner 2007b).

Agnosic presentations of Alzheimer’s disease are well-recognised, sometimes described as posterior cortical atrophy (PCA; although this syndrome may on occasion have pathological substrates other than AD: Crutch et al. 2012) or the visual variant of AD (Cogan 1985; Benson et al. 1988; Mendez et al. 2002; Caselli and Tariot 2010:84–91). These accounted for around 3 % of new AD cases seen in CFC over a 6-year period (2000–2005) (Larner 2006a). Although deficits in other cognitive domains, particularly memory, may be evident from the history or cognitive testing, sometimes the agnosic deficit is isolated, constituting an example of single domain non-amnestic MCI (Winblad et al. 2004); this has been encountered on occasion in CFC (Larner 2004a). Typically these individuals have already been seen by optometrists and/or ophthalmologists prior to referral with no cause for their visual complaint identified. They cannot differentiate between a normal and a backward clock (see Sect. 4.3.1; Larner 2007c).

Although FTLDs are classically associated with behavioural and linguistic problems with preserved visuoperceptual function, semantic dementia (SD) is recognised to encompass an associative agnosia, with impairment of object identification on both visual and tactile presentation, presumably a part of the semantic deficit in these patients. SD patients with predominantly non-dominant hemisphere degeneration may present with prosopagnosia (Thompson et al. 2003), a circumscribed form of visual agnosia characterised by an inability to recognise previously known human faces or equivalent stimuli (Larner 2011a:289–90).

Agnosia for faces accompanying lesions of the right hemisphere was originally described by Charcot (Luria 1980:378). The term prosopagnosia was coined by Bodamer in 1947, although the phenomenon had been described toward the end of the nineteenth century by Quaglino in 1867 (Della Sala and Young 2003) and Hughlings Jackson in 1872 and 1876, as well as by Charcot in 1883. Brief accounts thought to be suggestive of prosopagnosia have been identified in writings from classical antiquity by Thucydides and Seneca (De Haan 1999). A developmental form of prosopagnosia is also described, which may cause significant social difficulties (McConachie 1976; De Haan and Campbell 1991; Nunn et al. 2001; Rizek Schultz et al. 2002; Fine 2011), as demonstrated by a patient seen in CFC (Larner et al. 2003b; Case Study 7.3).

Case Study 7.3: Developmental Prosopagnosia

Assessed in his thirties, this man gave a history of lifelong difficulty identifying people by their faces, despite otherwise normal physical and cognitive development. Examples included failure to identify the faces of fellow pupils when a schoolboy, to identify familiar customers in the work environment, to recognize his wife in the street unless she was wearing familiar clothes, and to identify his children when collecting them from school. However, in his work as an optician, he was easily able to recognize different makes of spectacle frame. His neurological examination was unremarkable, with normal visual acuity, visual fields (confirmed by automated perimetry) and fundoscopy, and there was no achromatopsia. His reading was fluent, and there were no obvious perceptual difficulties.

Neuropsychological assessment included: the WAIS-R (above average intelligence: Verbal IQ 128; Performance IQ 113, but impaired on Object assembly subtest); Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP) battery, on which all subtests (incomplete letters, silhouettes, object decision, progressive silhouettes) were above relevant 5 % cut-off scores; the Birmingham Object Recognition Battery (BORB), on which all subtests were above relevant 5 % cut-off scores; Warrington Recognition Memory Test, on which words were normal but faces impaired; the Graded Naming Test and the Boston Naming Test on both of which scores were in the normal range. On the Benton Facial Recognition Test (matching faces according to identity) he scored 40/54 (borderline impaired; excessively slow performance). On the Young and Flude Face Processing Tasks he was impaired on the identity matching task (39/48; >3 SD below control mean) and on gender identification (39/48; 2 SD below control mean), but normal on identification of emotional expression (47/48) and eye gaze direction (16/18). He had no subjective awareness that animals might have faces, a possible example of zooagnosia (Larner 2011a:381).

Akinetopsia is the name given to a specific inability to see objects in motion whilst perception of other visual attributes remains intact, which may reflect lesions of area V5 of visual cortex (Zeki 1991; Larner 2011a:15). Rarely described, a possible example of akinetopsia has been seen in CFC (Larner 2005b; Case Study 7.4). Neuropsychological deficits following carbon monoxide poisoning may be very focal, as for example in a renowned case of visual form agnosia (Goodale and Milner 2004).

Case Study 7.4: Possible Akinetopsia

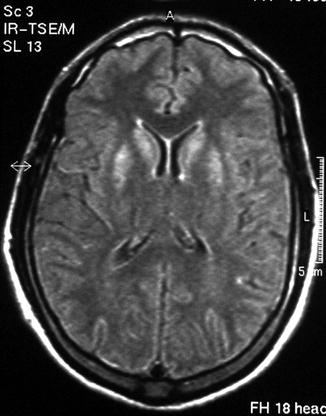

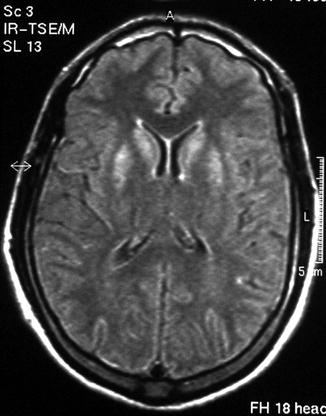

A male patient in his twenties attempted suicide by deliberate carbon monoxide poisoning (acute carboxyhaemoglobin = 44.6 %). On recovery from his acute illness, he complained of difficulty seeing, was unable to fixate or follow visual targets such as the examiner’s face, but had normal voluntary saccadic eye movements in both amplitude and velocity. He had “leadpipe” rigidity in all four limbs but there was no tremor. He could walk only with assistance because of his visual difficulty. A diagnosis of delayed parkinsonism with visual agnosia secondary to carbon monoxide poisoning was made. Eventually he could ambulate without assistance but still found it difficult to perceive moving as opposed to stationary objects. Subsequent neuropsychological assessment confirmed an apperceptive visual agnosia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed bilateral high signal intensity in the caudate and putamen (Fig. 7.3), accounting for his parkinsonism, as well as some subtle bilateral parieto-occipital cortical signal change more rostrally, perhaps accounting for his visual agnosia.

Figure 7.3

MRI brain showing bilateral high signal intensity in caudate and putamen following carbon monoxide poisoning. Patient had transient parkinsonism and persistent akinetopsia (Larner 2005b)

Macdonald Critchely described personification of paralysed limbs in hemiplegics following an initial anosognosia (unawareness of deficit), reporting patients who called their hemiplegic limbs “George”, “Toby”, “silly billy”, “floppy Joe”, “baby”, “gammy”, “the immovable one”, “the curse”, “lazy bones”, and “the nuisance”. Patients often showed a detached attitude towards their deficit which was treated with insouciance and cheerful acceptance. Most cases occurred in the context of left hemiplegia (Critchley 1955). A case of personification of a presumed functional neurological disability has been seen in CFC, although it was not apparent whether this was an anosognosic problem (Larner 2010c).

7.1.4 Praxis: Apraxia

Apraxia is an acquired syndrome of impaired voluntary movement despite an intact motor system with preservation of automatic/reflex actions (Larner 2011a:38–9).

Of the neurodegenerative disorders, corticobasal degeneration (CBD) was typified in its early descriptions, emanating from movement disorders specialists, as showing unilateral limb apraxia, sometimes with the alien limb phenomenon (e.g. Gibb et al. 1989). However, it has become increasingly apparent that CBD phenocopies, labelled as corticobasal syndrome (CBS), are relatively common, with the underlying pathology often being Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. Boeve et al. 1999, 2003; Alladi et al. 2007) and sometimes Pick’s disease. Occasional cases of CBS with underlying AD or Pick-type pathology have been seen in CFC (Doran et al. 2003). Apraxic presentations of Alzheimer’s disease are now well-recognised (Caselli and Tariot 2010:96–104), but rare: only one apraxic presentation was seen amongst new AD cases seen in CFC over a 6-year period (2000–2005) (Larner 2006a).

7.1.5 Executive Function: Dysexecutive Syndrome

Dysexecutive syndrome is an acquired syndrome of deficits in executive function, a broad umbrella term which may encompass such functions as problem solving, planning, goal-directed behaviour, and abstraction (Larner 2011a:117–8). In view of the heterogeneity of this construct, no one test can adequately probe “executive function”, but a variety of neuropsychological tests may address elements of it, including the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, word and design fluency tasks, proverb interpretation, cognitive estimates, Stroop task, and gambling tasks (Iowa, Cambridge). Impairments in these various cognitive tasks may be accompanied by (and indeed result from) behavioural dysfunction, ranging from disinhibition with loss of social mores to abulia, apathy and social withdrawal. The variety of behavioural (or neuropsychiatric) features seen in this syndrome means that these patients may present initially to psychiatric services, with suspected manic or depressive disorders. Because of the overlap of neurologic and psychiatric symptomatology, these patients are often referred to the clinic by psychiatrists (see Sect. 1.2.2).

Executive dysfunction is typical of the behavioural (or frontal) variant of FTLD (bvFTD), and may emerge with time in the other, linguistic, FTLD phenotypes (Sect. 8.2). The executive impairments found may permit differential diagnosis of FTLD from AD (Bozeat et al. 2000), and their assessment is incorporated into certain screening instruments such as the Cambridge Behavioural Inventory (see Sect. 5.2.1). In contrast to the impulsiveness which compromises the performance of bvFTD patients on gambling tasks, a patient with SD has been seen who was still able to bet regularly on horse racing with moderate success despite being essentially mute (Larner 2007d).

The question as to whether a frontal variant of AD (fvAD) exists has been approached in two different ways. Some have defined such a variant based on neuropsychological assessments suggesting a disproportionate impairment of tests sensitive to frontal lobe function. For example, Johnson et al. (1999) reported a group of 63 patients with pathologically confirmed AD, of whom 19 were identified with greater neurofibrillary pathology in frontal as compared to entorhinal cortex, of whom three had disproportionately severe impairment on two neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function (Trail Making Test A, FAS fluency test) at the group level. No details of the clinical, as opposed to the neuropathological and neuropsychological, phenotype of these patients were given, for example whether they presented with behavioural dysfunction akin to that seen in bvFTD. Woodward et al. (2010) defined cases of fvAD as AD subjects scoring in the lowest quartile of scores on the Frontal Assessment Battery (Dubois et al. 2000; see Sect. 4.11). Using other assessment scales, these fvAD patients appeared to be simply more severely affected AD patients. In contrast to this approach based on neuropsychological test performance, others have defined a frontal AD variant based on a clinical picture suggestive of bvFTD but with additional investigation evidence suggestive of AD (Larner 2006c; Caselli and Tariot 2010:104–8), although neuropathological confirmation of such cases is rare (e.g. Alladi et al. 2007; Taylor et al. 2008). Some AD patients with presenilin 1 gene mutations (Sect. 6.3.1) may have a phenotype suggestive of bvFTD (Larner and Doran 2006, 2009; Larner 2013b). One PSEN1 mutation (G183V) has been reported in which there was not only the clinical but also the neuropathological phenotype of bvFTD (Dermaut et al. 2004). One family, with the R269G PSEN1 mutation, with prominent behavioural and psychiatric symptoms, has been seen in CFC (Doran and Larner 2004).

Marked executive dysfunction producing a frontal type of dementia has also been encountered in a patient with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD), confirmed on clinical, biochemical and neurogenetic grounds, who was inadequately compliant with his treatment regime (Larner 2003a). Cases of X-ALD presenting with adult onset dementia have only rarely been reported, some with prominent frontal lobe dysfunction (e.g. Powers et al. 1980) and some with behavioural features (“manic-depressive psychosis”) which might possibly have been indicative of frontal lobe involvement (Angus et al. 1994).

7.2 Comorbidites

The comorbidities of cognitive disorders, both psychiatric and physical, have attracted greater attention in recent times (Kurrle et al. 2012). Their presence may be apparent on history taking (see Chap. 3) but may require the use of dedicated screening instruments for their identification (see Chap. 5).

7.2.1 Behavioural and Neuropsychiatric Features

The ubiquity of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) has been increasingly recognised (Ballard et al. 2001; Savva et al. 2009), not least because they, rather than cognitive impairments, are the most common antecedents of nursing home placement, the most costly aspect of dementia care. Since the assessment and treatment of BPSD lies outwith the training and expertise of most neurologists, and because of the close links between CFC and local old age psychiatry facilities, patients developing BSPD have typically been referred on rather than managed in house. Moreover, because some antipsychotic medications used to treat BPSD have been associated with an excess mortality secondary to cerebrovascular disease, behavioural rather than pharmacotherapeutic approaches are now recommended.

The FTLDs are often accompanied by non-cognitive neuropsychiatric manifestations such as apathy, disinhibition, loss of insight, transgression of social norms, emotional blunting, and repetitive and stereotyped behaviours (Mendez et al. 2008a). In a series of FTD/MND patients reported from CFC, over two-thirds were under the care of a psychiatrist at time of diagnosis, some with provisional diagnoses of hypomania or depression, and all of whom were receiving either antidepressant or neuroleptic medications, sometimes in addition to anti-dementia drugs, suggesting that neuropsychiatric symptoms are not uncommon in this condition (Sathasivam et al. 2008). Psychotic symptoms including delusions and hallucinations are, however, rarely seen in FTLDs (Mendez et al. 2008b). FTD/MND may be an exception to this rule, sometimes manifesting an early psychotic phase characterised by hallucinations and delusions which may be dramatic and bizarre but transient. A case of FTD/MND presenting with De Clerambault’s syndrome (erotomania) has been reported (Olojugba et al. 2007), and a patient with delusion of pregnancy related to c9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion has been seen in CFC (Larner 2008d, 2013c; Case Study 5.1). This mutation has also been associated with presentations as obsessive-compulsive disorder (Calvo et al. 2012) and bipolar disorder (Floris et al. 2013). A schizophrenia-like psychosis has been reported on occasion as the presenting feature of early-onset FTLD (Velakoulis et al. 2009) but there does not seem to be an association between c9orf72 and schizophrenia (Huey et al. 2013), although a patient with a provisional diagnostic label of “undifferentiated schizophrenia” who eventually developed neurological signs and proved to have this mutation has been encountered (Ziso et al. 2014).

Visual hallucinations are included amongst the core criteria in the diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (McKeith et al. 1996, 1999, 2005). These are usually complex images of people or animals, although the sensation of a presence, someone standing beside the patient (anwesenheit; Larner 2011a:34), is also relatively common in parkinsonian syndromes (Fénélon et al. 2000). A pathologically confirmed case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was initially mistaken for DLB because of the presence of visual hallucinations (simple colours rather than complex shapes) as well as motor features of parkinsonism and orthostatic hypotension, but the very rapid progression prompted diagnostic re-evaluation. Post mortem neuropathology was consistent with the MV1 subtype (Parchi et al. 1999; Du Plessis and Larner 2008). The Heidenhain variant of sporadic CJD, accounting for perhaps 20 % of cases, is characterized by visual disorders throughout the disease course which may include blurred vision, diplopia, visual field restriction, metamorphopsia, cortical blindness, and visual hallucinations (Kropp et al. 1999; Armstrong 2006).

Progressive psychiatric disturbances are one of the typical and often early features of variant CJD (Spencer et al. 2002) but these may also occur on occasion in sporadic CJD. Psychiatric features are the presenting feature in around 20 % of sCJD patients (Wall et al. 2005; Rabinovici et al. 2006), although not mentioned in diagnostic criteria. We have experience of a patient with a psychiatric prodrome diagnosed as depression for many months before progressive cognitive decline and investigation features typical of sCJD became apparent (Ali et al. 2013).

7.2.2 Delirium

Delirium is a clinically heterogeneous syndrome characterised by cognitive and behavioural features, diagnostic criteria for which require disturbance of consciousness (which may take the form of subtle attentional deficits only), change in cognition, and onset over a short period of time with fluctuation during the course of the day (Larner 2004b). It is a richly varied syndrome ranging from hypoactive to hyperactive states, with a number of recognised precipitating factors (infection, metabolic derangement, various medications) and predisposing factors (age, medical comorbidity, visual and hearing impairment). Dementia is one of the recognised predisposing factors for delirium, and the differential diagnosis may be difficult, since the two may coexist (“delirium superimposed on dementia”; Morandi et al. 2012).

It is exceptionally unusual for delirium per se to present in an outpatient setting, such as CFC, rather than acutely, although a history of previous episodes of unexplained confusion may be obtained in patients presenting to the clinic with cognitive impairments or dementia. Use of the Confusion Assessment Method may assist with the diagnosis of delirium (Wong et al. 2010a), but it may sometimes be necessary to institute empirical therapy for presumed delirium (i.e. review medications, treat underlying infection, correct metabolic abnormalities, reduce sensory impairments).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree