Diencephalon: Introduction

Thalamus

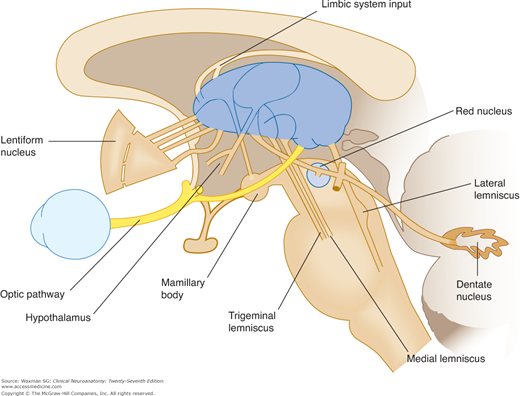

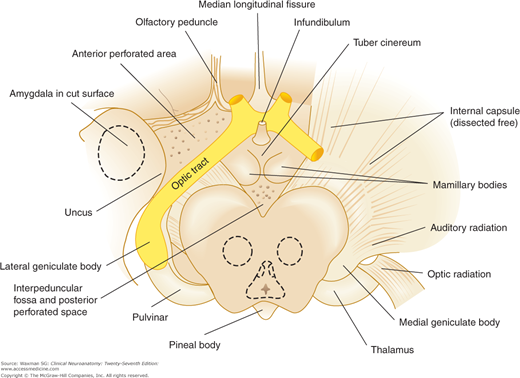

Each half of the brain contains a thalamus, a large, ovoid, gray mass of nuclei (Fig 9–2). Its broad posterior end, the pulvinar, extends over the medial and lateral geniculate bodies. The rostral thalamus contains the anterior thalamic tubercle. In many individuals, there is a short interthalamic adhesion (massa intermedia) between the thalami, across the narrow third ventricle (see Fig 9–1).

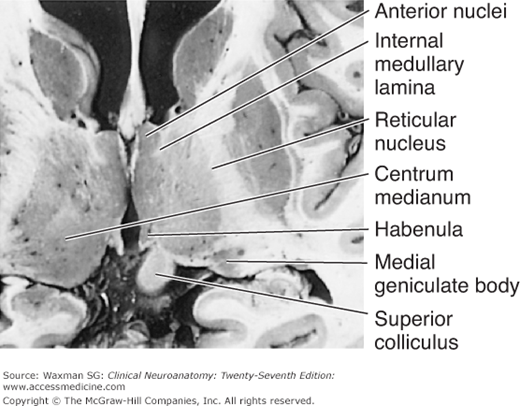

The thalamic radiations are the fiber bundles that emerge from the lateral surface of the thalamus and terminate in the cerebral cortex. The external medullary lamina is a layer of myelinated fibers on the lateral surface of the thalamus close to the internal capsule. The internal medullary lamina is a thin vertical sheet of white matter that bifurcates in its anterior portion and thus divides the gray matter of the thalamus into lateral, medial, and anterior portions (Fig 9–3).

There are five major groups of thalamic nuclei, each with specific fiber connections (Figs 9–3 and 9–4; Table 9–1).

Type | Nucleus |

|---|---|

Sensory | Lateral geniculate |

Medial geniculate | |

Ventral posterolateral | |

Ventral posteromedial | |

Motor | Ventral anterior |

Ventral lateral | |

Limbic | Anterior |

Dorsomedial | |

Multimodal | Pulvinar |

Lateral posterior (posterolateral) | |

Lateral dorsal (dorsolateral) | |

Intralaminar | Reticular |

Centrum medianum | |

Intralaminar |

This group of clusters of neurons forms the anterior tubercle of the thalamus and is bordered by the limbs of the internal lamina. It receives fibers from the mamillary bodies via the mamillothalamic tract and projects to the cingulate cortex of the cerebrum.

These groups of cells are located just beneath the lining of the third ventricle and in the interthalamic adhesion. They connect with the hypothalamus and central periaqueductal gray matter. The centromedian nucleus connects with the cerebellum and corpus striatum.

These include most of the gray substance medial to the internal medullary lamina: the intralaminar nuclei as well as the dorsomedial nucleus, which projects to the frontal cortex.

This constitutes a large part of the thalamus anterior to the pulvinar between the internal and external medullary laminas. The mass includes a reticular nucleus between the external medullary lamina and the internal capsule; a ventral anterior nucleus (VA), which connects with the corpus striatum; a ventral lateral nucleus (VL), which projects to the cerebral motor cortex; a dorsolateral nucleus, which projects to the parietal cortex; and a ventral posterior (also known as ventral basal) group, which projects to the postcentral gyrus and receives fibers from the medial lemniscus and the spinothalamic and trigeminal tracts.

The ventral posterior group of thalamic nuclei is divided into the ventral posterolateral (VPL) nucleus, which relays sensory input from the body, and the ventral posteromedial (VPM) nucleus, which relays sensory input from the face. The ventral posterior nuclei project information via the internal capsule to the sensory cortex of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere (see Chapter 10).

These include the pulvinar nucleus, the medial geniculate nucleus, and the lateral geniculate nucleus. The pulvinar nucleus is a large posterior nuclear group that connects with the parietal and temporal cortices. The medial geniculate nucleus, which lies lateral to the midbrain under the pulvinar, receives acoustic fibers from the lateral lemniscus and inferior colliculus. It projects fibers via the acoustic radiation to the temporal cortex. The lateral geniculate nucleus is a major way station along the visual pathway. It receives most of the fibers of the optic tract and projects via the geniculocalcarine radiation to the visual cortex around the calcarine fissure. The geniculate nuclei or bodies appear as oval elevations below the posterior end of the thalamus (Fig 9–5).

The thalamus can be divided into five functional nuclear groups: sensory, motor, limbic, multimodal, and intralaminar (see Table 9–1).

The sensory nuclei (ventral posterior group including VPL and VPM, and the lateral and medial geniculate bodies) are involved in relaying and modifying sensory signals from the body, face, retina, cochlea, and taste receptors (see Chapter 14). The thalamus is thought to be the crucial structure for the perception of some types of sensation, especially pain, and the sensory cortex may give finer detail to the sensation.

The thalamic motor nuclei (ventral anterior and lateral) convey motor information from the cerebellum and globus pallidus to the precentral motor cortex. The nuclei have also been called motor relay nuclei (see Chapter 13).

Three anterior limbic nuclei are interposed between the mamillary nuclei of the hypothalamus and the cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex. The dorsomedial nucleus receives input from the olfactory cortex and amygdala regions and projects reciprocally to the prefrontal cortex and the hypothalamus (see Chapter 19).

The multimodal nuclei (pulvinar, posterolateral, and dorsolateral) have connections with the association areas in the parietal lobe (see Chapter 10). Other diencephalic regions may contribute to these connections.

Other, nonspecific thalamic nuclei include the intralaminar and reticular nuclei and the centrum medianum; the projections of these nuclei are not known in detail. Interaction with cortical motor areas, the caudate nucleus, the putamen, and the cerebellum has been demonstrated.

Clinical Correlations

The thalamic syndrome is characterized by immediate hemianesthesia, with the threshold of sensitivity to pinprick, heat, and cold rising later. When a sensation, sometimes referred to as thalamic hyperpathia, is felt, it can be disagreeable and unpleasant. The syndrome usually appears during recovery from a thalamic infarct; rarely, persistent burning or boring pain can occur (thalamic pain).

Hypothalamus

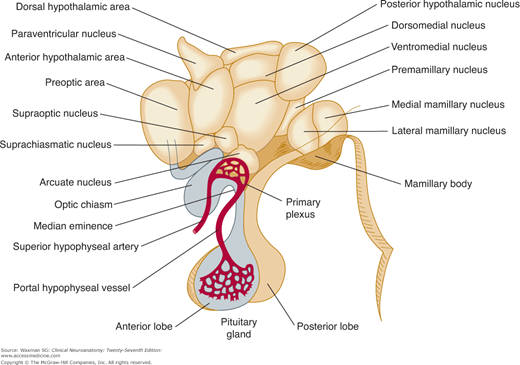

The hypothalamus, which serves a number of autonomic, appetitive, and regulatory functions, lies below and in front of the thalamus; it forms the floor and lower walls of the third ventricle (see Fig 9–1). External landmarks of the hypothalamus are the optic chiasm; the tuber cinereum, with its infundibulum extending to the posterior lobe of the hypophysis; and the mamillary bodies lying between the cerebral peduncles (Fig 9–6).

The hypothalamus can be divided into an anterior portion, the chiasmatic region, including the lamina terminalis; the central hypothalamus, including the tuber cinereum and the infundibulum (the stalk connecting the pituitary to the hypothalamus); and the posterior portion, the mamillary area (Fig 9–7).

Figure 9–7

Coronal sections through the diencephalon and adjacent structures. A: Section through the optic chiasm and the anterior commissure. B: Section through the tuber cinereum and the anterior portion of the thalamus. C: Section through the mamillary bodies and middle thalamus. D: Key to the section levels.

The right and left sides of the hypothalamus each have a medial hypothalamic area that contains many nuclei and a lateral hypothalamic area that contains fiber systems (eg, the medial forebrain bundle) and diffuse lateral nuclei.

Each half of the medial hypothalamus can be divided into three parts (Fig 9–8): the supraoptic portion, which is farthest anterior and contains the supraoptic, suprachiasmatic, and paraventricular nuclei; the tuberal portion, which lies immediately behind the supraoptic portion and contains the ventromedial, dorsomedial, and arcuate nuclei in addition to the median eminence; and the mamillary portion, which is the farthest posterior and contains the posterior nucleus and several mamillary nuclei. There is also the preoptic area, a region that lies anterior to the hypothalamus, between the optic chiasm and the anterior commissure.