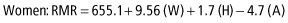

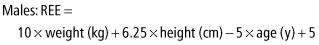

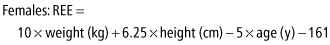

These equations use weight (W) in kilograms (kg), height (H) in centimeters (cm), and age (A) in years.

The Mifflin and St. Jeor equations are:

RMR can be measured using indirect calorimetry rather than estimated through prediction equations (Box 17-2). This is especially useful in the obese population, where prediction equations are less accurate (5). While until recently measurement of RMR by indirect calorimetry was only possible in a laboratory setting, the development of hand-held indirect calorimeters such as the MedGem®, BodyGem® and Futrex® has made RMR measurements accessible to the clinician.

Box 17-2 Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry is used to examine rates of energy use and substrate/food/nutrient oxidation in humans. It is called “indirect” because energy (calorie) use is calculated from a measurement of oxygen uptake. Oxygen uptake is determined from the volume of expired air and the concentration of oxygen in the expired air.

To determine total energy expenditure, RMR is multiplied by an activity factor (6). For example, if a woman has a basal energy requirement of 1,500 kcal/day and is relatively sedentary, her basal requirement would be multiplied by 1.5 to estimate the maintenance energy needs with activity included (7). A dietary regimen for weight loss would be designed to provide a reasonable calorie deficit compared to estimated maintenance needs. Energy intake less than that required for basal metabolism and physical activity may negatively affect reproductive hormones and osteogenesis in women, therefore particular care should be taken in determining the appropriate energy deficit for young women (8). It is important to remember that as a person loses weight, resting metabolic rate declines due to a combination of a smaller body size and the increase in energy efficiency that is observed after weight loss (9).

An energy deficit can be achieved by reducing energy intake, increasing energy expenditure through physical activity, or a combination of both. Current recommendations emphasize the benefits of the combination approach. Although increasing physical activity alone is less effective for weight loss, particularly in women, it is imperative for weight maintenance, and activity itself is critical for health. Even if additional weight loss does not occur, developing an exercise habit early is the best way to ensure that weight loss is maintained. An active person improves fitness and normalizes blood chemistry, and can maintain a healthier weight more successfully than an inactive person. Indeed, data from the National Weight Control Registry, whose members have maintained a weight loss of at least 13.5 kg for one year or more, indicate that individuals who maintain such weight loss are expending more than 2,200 kcal in physical activity weekly (see Chapter 22) (10). Although this amount of energy expenditure could prevent the weight gain expected from an extra piece of cake eaten daily, it does not reach the approximate number of calories needed to lose even 0.5 kg per week.

Thus far, there is no magic to one weight-loss diet against another. All dietary regimens for weight loss change the amounts of carbohydrate, protein, and/or fat, and possibly alcohol, to reduce calorie intake. The healthiest approach, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is to follow the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (11) to increase physical activity and reduce calories by limiting unhealthful foods such as added sugars, saturated fats, and alcohol, all of which provide calories but few or no essential nutrients. For some, this strategy is enough to achieve the energy deficit necessary for weight loss.

For most, however, the solution is not so simple. Many of us cannot be vigilant enough to defend against an obesogenic environment seven days a week, 24 hours a day. Support is often necessary to develop new food preferences and change long-standing behaviors that led to weight gain. Large portion sizes and a lack of awareness of the calorie content of foods, coupled with inadequate physical activity, add to the difficulty in achieving the intended results.

Clinical Goals for Weight Loss

If one were to create the perfect weight-loss diet, it would be something a dieter could adhere to for a lifetime; it would result in slow, steady weight loss followed by long-term weight maintenance; and it would be moderately low in calories but adequate in all other nutrients. In reality, weight-loss diets are usually adhered to for a short time only, weight regain is extremely common, the rate of weight loss is variable, and the dietary regimen is often inadequate in at least some vitamins and minerals.

The best dietary and behavioral treatments typically result in a 10% weight loss during the first six months of treatment. Continued contact between the dieter and a practitioner significantly enhances weight loss maintenance. In addition, regular physical activity is a consistent predictor of maintenance of weight loss. Nonetheless, weight regain is the most frequent long-term outcome of obesity treatment. The lack of long-term efficacy, as well as the hard work of day-to-day vigilance, fuels the popularity of approaches that are marketed as “easy” or “a sure thing.”

Maintaining a negative energy balance is extremely difficult when genetic susceptibility for obesity is combined with an environment that promotes it. Dieting strategies must take individual preferences into account. Surprisingly, research has shown that many of the diets that on the surface seem to be unhealthful result in improved metabolic profiles, lowering blood pressure, blood glucose, LDL-cholesterol, and other indices during the weight-loss period, though there are few data on these indices during maintenance of weight loss. Very-low-carbohydrate diets, such as the Atkins Diet, that for years were deemed unhealthy, are examples of this. In the short term, they actually seem to confer some advantage, particularly for lowering serum triglycerides, compared to low-fat diets, although this will vary with the individual genetics of the subject. At the same time, it is important to note that some dieters have had to drop out of such programs because of significantly elevated LDL-cholesterol levels (12).

The adage “diets don’t work” should be amended: diets do work, as long as the dieter follows them. Attrition in most studies is high (13). In the long term, the magnitude of weight loss for all diets is similar and short-term advantages disappear (14). Dieters must be clear on one important caveat—individual health outcomes differ in important ways. Regardless of the diet, all dieters need periodic evaluations by their primary care physicians. When possible, accepted dietary guidelines should be promoted, as disease risk may be increased even without weight loss.

Diet Strategies

Very-Low-Calorie Vs. Low-Calorie Diets

A very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) is defined as 800 kcal or less per day; it should be physician-supervised (15, 16) and only undertaken when the BMI is 30 kg/m2 or more, indicative of obesity. The number of calories prescribed is usually a uniform number for all patients and depends on the product dispensed, and is therefore not subtracted from the calories required for maintenance. Thus the clinical risks may differ as the gap between assigned calories and maintenance calories increases. For example, an 800 kcal diet might result in a slow weight loss in a woman who is five feet tall and sedentary, while an 800 kcal diet for a six foot, active man may represent a severe calorie deficit and result in more rapid weight loss than is safe. The degree to which calories are reduced will affect the speed of weight loss and may result in an unhealthy loss of lean tissue. Too large a deficit, therefore, may be counterproductive. Rapid weight loss increases the risk for gallbladder disease, heart arrhythmias, and lean tissue loss, among other risks (17). Guidelines for weight loss recommend medical supervision for all diets providing 1,000 kcal or less because of these increased health risks (National Heart Lung Blood Institute (NHLBI) Clinical Guidelines).

VLCDs were developed in the 1920s as a vehicle for achieving more dramatic weight losses than were possible with regular food diets, while reducing the complications that occurred with total starvation. The most popular VLCDs are liquid formulas (e.g., Optifast™, HMR™). Because these foods are processed in a food blender, extra nutrients can be added without extra calories, resulting in a nutrient-rich product with over 100% of the recommended dietary allowances of vitamins and minerals, all in a very-low-calorie package. These formulas are in powdered or liquid form, and their protein is usually from milk and soy. They used to be the sole source of nutrition for users, but many VLCDs are now accompanied by low-calorie, freeze-dried, or packaged meals. Calorie prescriptions are specific and inflexible (e.g., 800 kcal per day) and the number of meals provided depends on the mixture of packaged vs. liquid choices. The protein content is relatively high (usually >84 g) and fat content is low (often <10 g). The product (food/drink) is usually bought at a medical center or physician’s office but can be bought on the internet as well. These diets can be very effective for rapidly improving some of the parameters of diseases that are associated with obesity, such as uncontrolled diabetes, sleep apnea, and hypertension. However, patients need a very thorough work-up before starting such a diet in order to ensure that the dieter (and the heart) can endure such rapid weight change; recidivism will occur unless behavioral changes are made once re-feeding starts. A serious disadvantage of this diet is that it is not comprised of regular food and, therefore, socializing can be limited. They are also expensive and long-term studies do not show better efficacy than with low-calorie diets. That said, the major suppliers of VLCDs include a six-month behavioral program plus weight maintenance education for patients to help improve adherence and weight-loss maintenance.

VLCDs are usually prescribed for no more than 16 weeks, at which point a re-feeding diet is commenced. The return to regular food can take four weeks or longer, depending on the patient, during which an interim diet of part-formula and part-regular food is consumed. The calories are slowly increased to low-calorie status, although the diet remains hypo-caloric until maintenance.

VLCDs usually result in weight losses of 13−23 kg as compared with the 9−13 kg losses from low-calorie diets (18). Long-term weight maintenance is variable at best. Although, in general, studies indicate that less weight is regained if the dieter has long-term weight maintenance support, treatment guidelines do not suggest such support as a long-term strategy (19).

There are also VLCDs consisting of solid food. Called protein-sparing-modified fasts, they are comprised almost entirely of lean protein foods (i.e., chicken, fish, lean beef), and are therefore low in several nutrients such as vitamins, fiber, and some minerals. One advantage, however, is that they are more socially acceptable. These diets, like all VLCDs, require physician supervision.

Low-calorie strategies are less expensive than very-low-calorie approaches; they are also safer, and scientific studies show similar efficacy as reflected in weight loss after one year. As a group, low-calorie diets (LCDs) usually provide 1,200−1,500 kcal/day and are intended to induce a more modest energy deficit than VLCDs. Thus, weight loss is slower on LCDs than VLCDs, and physician supervision is not always necessary. In more recent studies, LCDs have been defined by the energy deficit they induce—500−600 kcal/day—yielding an approximate weight loss of 0.5 kg per week (500 kcal × 7 days = 3,500 kcal, or about 0.5 kg fat). This rate of loss conforms to national guidelines that recommend a dieting weight loss of 0.5−1 kg per week. It is sensible that the majority of diets widely marketed are LCDs; marketing examples range from large commercial programs such as Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig, to popular diets promoted in books such as the Atkins and South Beach diets, to liquid meal replacements such as SlimFast or Glucerna.

In a recent meta-analysis of VLCDs vs. LCDs, the very-low-calorie diets resulted in greater short-term weight losses (16.1 ± 1.6% vs. 9.7 ± 2.4%, mean ± std deviation) but similar weight losses after one year (6.3% ± 3.2% vs. 5.0% ± 4.0%) (16). LCDs were less expensive and the absence of a requirement for physician supervision further reduces the cost. An LCD with a comprehensive program of lifestyle modification results in approximately 10% weight loss in the first 16−26 weeks. The Diabetes Prevention Program, a National Institutes of Health intervention to prevent diabetes in subjects who are glucose-intolerant, compared use of metformin or placebo to use of a LCD that was also low-fat and combined with 150 minutes of daily physical activity. The diet-plus-activity group lost 7% of their weight and reduced their conversion to diabetes by 58% as compared to the control group. The metformin group reduced their risk of developing diabetes by 31% (20).

One LCD strategy is to replace higher-calorie foods with less-energy-dense foods, such as fruits and vegetables, which give options for larger portions with fewer calories. Studies have observed an inverse relationship between body weight and consumption of dietary fiber and water-based foods (21). Proposed mechanisms include improved satiety, delayed nutrient absorption, and an alteration of gut hormones.

That said, following a diet with a 500 kcal deficit is hard. Many of those struggling with weight management are completely unaware of the energy content of foods and the energy cost of physical activity. Thus, they underestimate the amount of energy they consume and overestimate the amount of energy they expend. Unless the calorie content is listed on a food package, or the home recipe is measured precisely and calories counted for every ingredient, the dieter is estimating the ingredients and their amounts, and almost always underestimates calories (22). Further, many people frequently consume meals prepared outside of the home (23), making calorie counting an almost impossible job. Knowledge of portion size is essential for evaluating the calorie content of foods (24), but portions are also difficult to assess accurately. Clarifying this is often helpful to the dieter (Box 17-3). Greater accuracy is possible when a dieter measures commonly eaten items such as cereal, pasta, rice, oil, butter, margarine, and salad dressings, and uses this information to calculate calories. Once a dieter understands, for example, that 1 cup of his favorite cereal has 160 kcal and that he typically pours 2 cups, or that 1 tablespoon of oil has 120−126 kcal and he typically uses 2 tablespoons on a salad, a menu can be developed within the calorie allotment. The NHLBI provides a tutorial on “Portion Distortion,” which can be accessed online as an effective educational tool (25). The National Weight Registry participants continually show most success at weight maintenance from portion-controlling, even for fruits and vegetables (26).

Box 17-3 Serving Sizes Comparison Sheet

THE BREAD, CEREAL, RICE, and PASTA GROUP

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 cup of rice or pasta (2 servings) | a baseball |

| 1 pancake | a compact disc |

| 1/2 cup cooked rice | ½ a baseball |

| 1 piece of cornbread | a bar of soap |

| 1 slice of bread | a typical brand name slice |

| 1 cup of cereal flakes | a baseball |

THE VEGETABLE GROUP

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 cup salad greens | a baseball |

| 1 baked potato | a baseball |

| 3/4 cup tomato juice | ¾ of a baseball |

| 1/2 cup cooked vegetable | ½ a baseball |

THE FRUIT GROUP

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 serving of grapes | 12 grapes |

| 1 medium size fruit | a baseball |

| 1 cup of cut-up fruit (2 servings) | a baseball |

| 2 tablespoons raisins | a ping pong ball |

THE MILK, YOGHURT, and CHEESE GROUP

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 ½ ounces natural cheese | a 9-volt battery, 2 dominoes |

| 8 ounces milk. 1 cup | a baseball |

| 2 ounces sliced, processed cheese | a compact disc |

THE MEAT, POULTRY, FISH, DRY BEANS, and EGGS GROUP

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 2 tablespoons peanut butter | a ping-pong ball |

| 1 tablespoon peanut butter | a thumb tip |

| 3 ounces cooked meat, fish, poultry | a palm, a deck of cards or a cassette tape |

| 3 ounces grilled/baked fish | a checkbook |

| 3 ounces cooked chicken | a chicken drumstick and thigh, or a breast |

| ½ cup cooked beans (kidney, lima, garbanzo) | ½ a baseball |

FATS, OILS, and SWEETS

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 teaspoon butter, margarine | a fingertip |

| 2 tablespoons salad dressing | a ping-pong ball |

SNACK FOODS

| Food | Is about this size of … |

| 1 ounce of nuts | one handful (about 30 nuts) |

| 1 ounce chips or pretzels | two handfuls |

| ½ cup of potato chips, crackers, or popcorn | ½ of a baseball, or one man’s handful |

| 1/3 cup of potato chips, crackers, or popcorn | 1/3 of a baseball, one woman’s handful |

A serving size is an amount of food designated by the US government to be used on food labels. Calories listed on food labels are based on serving size. It is not necessarily the amount we should eat.

A portion size is the amount of food an individual chooses to eat. Individual portion sizes are highly variable and may actually be several serving sizes. Portion sizes at restaurants are typically very large and include many actual servings. For example, a chain restaurant portion size of spaghetti and meatballs can be as many as 10 servings of pasta and 3 servings of meat.

Understanding serving size and portion size helps people to better evaluate how many nutrients and calories they are consuming.

Portion Control Strategies: Meal Replacements

Meal replacements are used in diets as a strategy for replacing a higher-calorie meal with a nutritionally controlled, portion-controlled meal. It is a strategy that has been effectively used within the structure of a LCD to help people estimate calories more accurately. A meal replacement is pre-portioned food in liquid or solid form, packaged in a can, box, or bar, and frozen, dehydrated, refrigerated, or shelf-stable. It is not a supplement to a meal (such as a 220 kcal liquid drink in addition to a regular meal, most likely a scenario for weight gain, not weight loss). Used for weight loss, a meal replacement must have fewer calories than the meal it replaces.

There is no defined calorie content for a meal replacement, but over-the-counter meal replacements usually provide 180−300 kcal/serving and are used as part of a low-calorie diet of approximately 1,200−1,500 kcal. The diet is usually prescribed as two meal replacements plus one sensible meal of the dieter’s own choosing, with fruit or vegetables as snacks. Meal replacements can be bought in drugstores and grocery stores. Some of them include guidance on eating the sensible meal as well as behavioral modification suggestions. Many of the companies that manufacture these meal replacements have interactive websites where the dieter can get more information.

Meal replacements differ, depending on their formulation (Box 17-4). The variation is particularly apparent in meal replacement bars and in frozen food; liquid meal replacements tend to be more homogeneous and include approximately one-third of the Recommended Dietary Allowances for vitamins and minerals. Although fiber, protein, carbohydrate, and fat content differ depending upon the product, liquid meal replacements contain on average 10−14 g of protein, 3−8 g of fat, and 1−5 g of fiber.

Box 17-4 Tips for Home-made Meal Replacements

Meal Replacements can consist of any food that is portion controlled, repeatable, and where the calories can be clearly measured. In a study of Special K brands by Vanderwal and colleagues, using different cereal products twice each day as meal replacements produced a weight loss of more than 3 kg over 4 weeks (Vander Wal JS, McBurney MI, Cho S, Dhurandhar N, Ready-to-eat cereal products as meal replacements for weight loss. Int’l J Food Sci & Nut 2007; 58(5): 331−40). Hannum and colleagues compared a 1,365 calorie diet using regular food vs. frozen Uncle Ben’s Rice Bowls. Over eight weeks, the meal replacement group lost more weight, and had more significant changes in glucose and insulin than the conventional diet group.

Hannum SM, Carson LA et al. Use of packaged entrées as part of a weight-loss diet in overweight men: an 8-week randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2006; 8: 146−55.

On a simpler level, one could eat 85 g of turkey on two slices of whole wheat bread with lettuce and mustard and consume it with a glass of 1% milk as a meal replacement. Similarly, a can of soup, if eaten as a meal, would be a simple meal replacement.

There have been several randomized clinical trials of meal replacements, the majority of which have been sponsored by SlimFast (Unilever, Netherlands). The data show 6−12 months efficacy and safety, with significant decreases in health risk (27−28). Long-term weight loss and weight maintenance trials, which have been open-label and not randomized, have also shown efficacy (29). Most studies used two meal replacements per day during weight loss and one meal replacement per day for weight maintenance. Other, non-SlimFast studies include one randomized trial using Uncle Ben’s Rice Bowls versus a traditional low-calorie diet for eight weeks. Results showed a significantly greater weight loss, lower serum insulin, and lower serum glucose levels among the cohort using Uncle Ben’s (30).

Clearly, there are no magical properties to these foods, but the ability for a dieter to get pre-packaged, portion-controlled, calorie-labeled food for each meal is a big advantage. There has been some concern over the amount of sugar in some liquid formulations, particularly for people with type 2 diabetes. Heber and colleagues found no significant difference in the postprandial rise in serum glucose between those using Glucerna (a liquid meal replacement marketed to people with diabetes due its lower carbohydrate and higher fat content) and those using SlimFast (31). There may be little difference between these two formulations because calorie restriction, in and of itself, has a significant effect on serum glucose (32). There are so many types of liquid formulas that it would be fair to say that whichever liquid tastes better to the dieter, or is more satiating, or even less expensive, is the one that should be used.

One supportive study by Wing and Jeffrey found that meal replacements—even those that used conventional food portioned out by study coordinators—were more successful in inducing weight loss than monetary incentives (33). In another study, subjects who followed the meal replacement diet consumed more vegetables and fruit than those who followed the more conventional diet (34). This may be due to the clear guidelines given: meal replacements for two meals, with fruits and vegetables in between and one “sensible” meal. One caveat: meal replacements are most effective when they substitute for the largest meals. The “sensible” meal can be difficult to organize if it is prescribed at the highest risk time of the day for the client. For the clinically obese patient, meal replacements may be effective for the initial stages of weight loss, although ultimately the patient will need to learn other behavioral strategies to be successful in the long term.

The most famous meal replacement diet is probably the Subway diet. Jarrod (a person used widely in Subway’s marketing campaigns) lost more than 45 kg eating the same thing every day: coffee for breakfast; a six-inch turkey hero and baked potato chips for lunch; and a 12-inch vegetarian hero for dinner.

Categorizing Diets

Popular diets can be categorized into four groups: very high carbohydrate, low fat; very high fat, low carbohydrate; moderate fat, moderate carbohydrate; and gimmicks—those that cannot be categorized as easily by their macronutrients as they can by the diet prescription (such as the Cabbage Soup Diet, the Bagel Diet, the Three-Day Diet). To categorize a diet, one needs to know what macronutrients make up common categories of food. For example, a very-low-carbohydrate diet would eliminate almost all foods that contain carbohydrate including milk, starch, fruit, and vegetables; a diet high in carbohydrate and very low in fat would eliminate oils and red meats as well as high-fat dairy products. Moderate diets fall into the “variety” category and defy easy description because the longest phase of these diets does not omit specific food categories but rather, through a “trick,” tries to restrain consumption of certain categories. These diets tend to be more nutrient-rich than more restrictive diets, including at least some vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat milk, and healthy fats.

Some diets, such as Weight Watchers, DASH, Atkins, and Glycemic Index diets, have some research to support either their weight loss claims or their reduction in medical risk, and their length of time on the diet “scene” has helped make them more acceptable. Furthermore, DASH and the Mediterranean diets have data showing improvement in health outcomes without weight loss. But the preponderance of diets and diet books are fads—momentarily popular and professing ease and success, but with no research studies to prove efficacy. Instead, the attractiveness is in the “trick” such as adding one particular food that may have magical properties, or not combining certain foods at certain times.

Fad Diets

A fad diet typically has three features: 1) no scientific evidence that the diet works, but some science to support the idea that the diet might work; 2) a catchy name; and 3) some emphasis on a supposedly new, 100% effective discovery that a certain food should either be eliminated or increased to ensure weight loss success. This is how diets are marketed and how they distinguish themselves. Examples include the Belly Fat Diet, Skinny Bitches, Fat Smash Diet, South Beach, and French Woman’s Diet. The cover of a book presenting the diet will include words such as “fast,”, “eat what you want,” “see results in days” or “weeks” or even “hours,” “easy,” “minimum work,” and let us not forget “inflammation” and “insulin resistance,” all buzz-words for a fad diet, suggesting science (without any), magic, and (of course) 100% success (if you adhere to it unendingly). The secret to decoding these popular diets is to find the way that they reduce calories. A recent novelty is to propose a diet in phases or waves: phase 1 is most restrictive and may need physician sign-off, although it tends to be short term; phase 2 is the longer-term and more moderate weight-loss phase; and phase 3 is the maintenance phase.

All diets that result in weight loss do so on one basis and one basis only: they reduce total calorie intake, usually by reducing consumption of a category of food or limiting the diet to just a few key foods (the latter are mostly gimmicks). The bagel diet “suggests that your mother was right—you won’t eat your meal if you fill up your stomach before eating your meal.” The gimmick? The diet calls for a bagel before each meal, but each meal is limited to very-low-calorie foods such as lettuce leaves. The lettuce leaf meals are not prominent in the materials, but the popular three bagels per day is prominently displayed. These diets market the fact that you can eat all you want, but the end result is a low-calorie diet. There is no secret to weight loss; the success is determined by adherence. The popularity of the fad is usually short term and the book sells because it is hotly promoted and the public believes the hype.

Once the dieter or the health practitioner figures out the key components that will act as motivators, the next question is: Is the diet safe? It is important that the dieter be evaluated by a physician before starting any restrictive diet and that any other involved clinician confer with the physician before advising the patient. The rate of weight loss, the metabolic effect of weight loss, and the severity of calorie restriction are always a concern, particularly as to how they could affect body composition and prescription medication dosages. Nutrient adequacy is another concern. When do you need vitamin supplementation and what kind should the clinician suggest? As a general rule, a daily multivitamin can be helpful during any weight-loss diet. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation is important in any diet that restricts the intake of milk products. Another rule of thumb is to see whether an entire category of food is restricted, as in the case of very-low-carbohydrate diets where B vitamins, folate, and fiber may be deficient, or in very-low-fat diets where zinc, B12, and fat-soluble vitamin supplements may be needed. Gimmicks, such as the three-day diet, which suggest that the dieter choose one food per day for three days, are an extreme example of nutrient deficient weight-loss diets. This is also why most of them are very short term.

The dieter should beware of diet plans that include additional supplements sold only at diet headquarters. These diets are often just a marketing gimmick designed to ensure more supplement sales. If a supplement is needed when a special diet is used, the nutrients the diet lacks should be explicitly stated so that the dieter has the choice of buying supplements in a standard drug store or other location. If the supplement is a specific mixture that is not sold elsewhere, then written material should be provided of peer-reviewed, scientific data indicating the safety and efficacy of the supplement.

Dieters may follow fad diets with or without guidance from clinical professionals. Dieters focus on losing weight and may not realize that the diet works simply because energy intake is reduced. The clinician knows that there is no magic to a particular diet and may be concerned with the potential effects of nutrient deficiencies or unhealthy fat sources. If popular diets are approached with some openness by the clinician, there may be ways to design a reasonably healthy weight-loss program, even within the confines of a diet that promotes eliminating bread, staying within the “zone,” or avoiding carrots supposedly because they have a “high glycemic index” (GI).

Macronutrient Composition

When trying to understand the various approaches to weight management, it is useful to categorize diets based on their nutrient composition. The energy-yielding nutrients are protein, carbohydrates, and fats, and these must be manipulated to achieve an energy deficit. The US Dietary Guidelines recommend that dieters stay within the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR) for these nutrients, obtaining 10−35% of total calories from protein, 45−65% of total calories from carbohydrates, and 20−35% of total calories from fat (34). Alcohol is the only other source of calories. Other than the Drinking-Man’s Diet which was popular 40 years ago, most hypocaloric diets exclude or restrict alcohol.

Protein

Diets vary in the amount of protein they provide, ranging from 10% as recommended by the dietary guidelines to 40% for high-protein diets. The scientific rationale for increasing the protein portion of the diet is based on minimizing loss of lean tissue and maximizing satiety.

The RDA for protein is specifically for those in energy balance, but there is convincing evidence that it is inadequate when calories are restricted. Energy restriction is known to negatively affect nitrogen balance as protein is increasingly used as an energy source, and the RDA may be inadequate to protect against loss of lean mass during weight loss (35). A number of studies have compared diets providing the RDA for protein with those higher in protein. In one study, weight-loss diets using the RDA of 0.8 g protein/kg body weight were compared with diets providing 1.4 g protein/kg body weight among overweight and obese women over 12 weeks (35). The higher-protein diet preserved more lean body mass. In a similar study but with the addition of exercise, the higher-protein group lost more fat tissue compared with the group that was prescribed the RDA for protein (36). While more research is needed to precisely define the protein needs of dieters, a meta-analysis found that 1.05 g protein/kg body weight improves retention of lean body mass during energy restriction (37).

Diets labeled “high protein” vary in their protein content and are not necessarily higher than the typical American diet. In one example, researchers found that a high-protein diet, coupled with resistance training, was more effective in lowering body weight and favorably altering body composition than a control diet providing the RDA for protein (38). The test diet referred to as a high-protein diet provided only 1.12 g protein/kg body weight. Another study followed male and female dieters for one year including a four-month weight-loss phase followed by an eight-month maintenance phase (39). Subjects were randomized to one of two diets: 55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, 30% fat; or 40% carbohydrate, 30% protein, 30% fat. Total weight loss was the same for both groups, but subjects in the high-protein group lost more body fat and a higher percentage completed the study (64% vs. 45% completion for the lower-protein group). While this sounds promising for advocates of a high-protein diet, it must be noted that the lower-protein group was only getting the RDA of 0.8 g per kg body weight while the higher protein group received 1.6 g per kg body weight. Furthermore, there were significant standard deviations indicating a substantial variability in the individual response to the protocols.

There is evidence that protein may increase satiety when compared to lower-protein diets and that the subsequent meal is reduced in calories after a previous high-protein meal (40). This may partly explain the efficacy of diets higher in protein. Based on current research, it seems safe to conclude that the protein portion of an energy-restricted diet should be greater than the RDA, although there is no research to indicate by how much.

Fat

The message on dietary fat and weight loss is often confusing to the lay person. Weight loss usually improves the metabolic profile, no matter what the diet, and weight loss occurs when calories are reduced below maintenance requirements, no matter what the macronutrients. That said, there is a difference between the types of fat that are suggested in many of these diets. Saturated fats are known to be atherogenic. For example, in some studies of low-carbohydrate diets that did not restrict saturated fat, some subjects had to drop out due to significant increases in LDL-cholesterol (41). Dietary fats that are high in monounsaturates have a better metabolic profile and help improve lipid profiles. Some studies have suggested that these fats, particularly the omega-3 fatty acids, have a beneficial effect on body weight as well (42, 43), and diets that promote monounsaturated fats (such as the Mediterranean and DASH diets) usually promote foods that are high in fiber as well. Nonetheless, calories must be reduced for weight loss to occur. It is safe to say that, since any calorie-restricted diet will be successful if adhered to, diets low in dietary fat or high in dietary fat can show efficacy if this criterion is met. In one recent study looking at weight loss and adherence over two years, the low-carbohydrate diet and Mediterranean diet resulted in greater weight loss than the low-fat diets (44).

Public health messages to reduce dietary fat have not always resulted in a reduction in calories, however. Many consumers underestimate the calories in non-fat or low-fat foods, assuming a calorie savings where none may exist. Perceiving a niche for new products, food companies responded to the low-fat message with an array of fat-free foods including cookies, cakes, and ice cream, which typically provided negligible calorie savings over full-fat products, partly due to the increased proportion of sugar that results when other macronutrients are removed. The fat-free craze of the 1990s showed us that simply replacing fat with carbohydrates does not solve the obesity problem. Dieters switching their Oreos for low-fat Snackwells did not reduce total energy intake and consequently did not lose weight. Reducing dietary fat can be an effective means of calorie control provided that the calories are not replaced with calories from other sources. As with any diet, food choice is important to total health. When lowering dietary fat, particular attention must be paid to reducing saturated fat and consuming high-fiber, nutrient-rich carbohydrates to achieve health benefits (45).

Low- Vs. High-Glycemic Index Carbohydrates

The concept of glycemic index (GI) was originally introduced as a way of distinguishing the potential for different carbohydrates in equal amounts to increase blood sugar to different extents in people with diabetes. Carbohydrate foods are ranked by the degree to which they raise blood sugar immediately after consumption. These numbers are determined by averaging the blood sugar responses of several individuals to different foods. Their response is then compared with their response to a reference food: either white bread or glucose. Inconsistencies of the GI assigned to different foods may be due to different reference foods being used to assess the GI (46) or to individual variability in the response. Also, the GI will change when carbohydrates are combined with other macronutrients. The carbohydrates in most fruits, non-starchy vegetables, legumes, nuts, and dairy products tend to have a low GI, while those in potatoes, white breads, and sugary breakfast cereals are high GI. Foods that have a low GI tend to be promoted in diets with moderate carbohydrates. The theory is that higher GI foods increase insulin levels, which promotes fat retention (Box 17-5).

Box 17-5 Glycemic Index vs. Glycemic Load

GI compares 50 g of carbohydrate in a food to a control that contains either 50 g of glucose or an amount of white bread that contains 50 g of carbohydrate. The value is multiplied by 100 to represent a percentage of the control food. Foods that are low in carbohydrate, but release it readily, would have a high glycemic index. The GI allows comparison of the change in blood glucose in response to a given food. Foods that are considered complex carbohydrates may have different glycemic indices, and this may be important for people with diabetes. For instance, potatoes and rice are both considered complex carbohydrate foods, but potatoes result in about a 20% greater rise in glucose than rice does. Potatoes give 108% of the blood glucose response as the same amount of carbohydrate in white bread, rice yields 79% relative to white bread.

The glycemic index is not as useful as the glycemic load, which describes both the quality (glycemic index) and quantity of carbohydrate of a standard serving of that food. Glycemic load is calculated as GI × (g CHO)/100. Since GL, and not GI, takes into account the amount of carbohydrate in a standard serving, GL is more appropriate for use in evaluating diets.

For example, the mean GI was 78 ± 23 of four different types of carrots, using 50 g of carbohydrate from white bread as the comparison, but a typical serving of carrots contains only about 3−8 g of carbohydrate, resulting in a fairly low mean GL of 3.

Foster-Powell K, Holt SHA, Brand JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 76: 5–56.