(1)

Princeton Spine & Joint Center, Princeton, NJ, USA

Keywords

Intervertebral discAnnular tearNucleus pulposusMcKenzieEpiduralDiscographyDisc stimulation testIntradiscalThe intervertebral disc is the most common source of chronic lower back pain accounting for approximately 40 % of all cases [1]. It is important to emphasize from the outset that discogenic lower back pain is not the same thing as a herniated disc. A herniated disc may (and then again may not) irritate a nerve root and cause radicular symptoms [2]. However, a herniated disc in and of itself will not cause isolated lower back pain. If a tear in the disc is also present, then it may cause back pain whether or not a herniation is present.

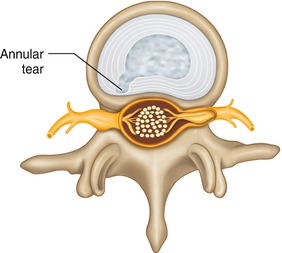

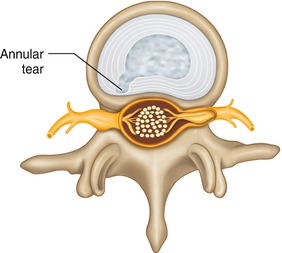

Recall from Chap. 1 that the intervertebral disc is similar to a jelly donut. The inside jelly of the disc is called the nucleus pulposus . The nucleus pulposus provides the disc with its shock-absorbing capacity, but it is also filled with proteins with inflammatory properties [3]. The outside crust of the disc is called the annulus fibrosus . In the outer third, and sometimes the outer two thirds of the annulus fibrosus, there are sensory nerve fibers. When discs cause lower back pain, it is because a tear has extended from the nucleus pulposus into the outer third (or possibly two thirds) of the annulus fibrosus, and inflammatory proteins have oozed out and are irritating the sensory nerve fibers in the outer annulus [4] (Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 5.1

Schematic depiction of an annular tear

Positions that put more pressure on the disc tend to increase discogenic lower back pain. In 1976, Dr. Nachemson evaluated the disc pressure in vivo in patients in various positions [5]. The results were largely confirmed by Dr. Wilke in 1999 [6, 7]. The two positions with the largest amount of pressure on the disc is sitting and bending forward and standing and bending forward at about 30° of flexion. Sitting in general also increases the pressure on the disc. This helps explain why patients with discogenic lower back pain often have increased pain with prolonged sitting. It also helps explain why so many patients report increased pain or onset of pain with otherwise seemingly innocuous activities such as opening a window, brushing teeth, or vacuuming. All of these activities involve about 30° of trunk flexion and therefore expose the disc to increased pressures. The increased pressure on the disc presumably irritates the sensory nerve endings that are inflamed in the disc.

In the morning, gravitational and hormonal factors lead to increased swelling in the disc, and therefore increased lower back pain in the morning is also common in patients with discogenic lower back pain. The hormonal factors are due to cortisol fluctuations during the diurnal cycle. The gravitational factors are interesting as they are due to the fact that during the day vertical gravitational forces compress the disc whether the person is sitting or standing. At nighttime, while lying down the gravitational forces are no longer vertical effectively off loading the disc allowing it to expand and fill with fluid. The increased fluid in the disc is minimal in volume but can be clinically meaningful when considering intradiscal pressures in which even small fluctuations can result in increased pain and discomfort in a disc with a symptomatic annular tear.

Positions that take the pressure off of the disc tend to make the back feel better in discogenic lower back pain. This is a guiding principal of McKenzie physical therapy exercises . Extending the lumbar spine decreases the pressure from the disc and therefore tends to relieve back pain in discogenic pain. A common stretch to relieve discogenic lower back pain is to stand with hands on hips and extend the lumbar spine backward (Fig. 5.2). Lying prone and raising oneself to his elbows in order to gently extend the spine is also a common stretch to relieve back pain in discogenic lower back pain (Fig. 5.3). Generally, positions of standing and lying down create lower pressure environments for discs than sitting and bending forward, and so patients with discogenic lower back pain tend to report less pain with lying down and standing as opposed to sitting and bending forward.

Fig. 5.2

Standing extension stretch

Fig. 5.3

Prone extension stretch

Consider the following patient. A 34-year-old male named Jake presents with 6 months of lower back pain that began after lifting a heavy television set. The pain began gradually after lifting the television but then became progressively more intense. The pain does not radiate. The pain is worse with sitting and bending forward. The pain is worse in the morning. The pain is better with standing and extending backward.

If Jake’s case were presented to a 100 fellowship-trained spine specialists and asked for a presumptive diagnosis, it would be a safe bet that almost all of them (or perhaps all) would think that discogenic lower back pain were the most likely source of Jake’s pain. The interesting—and arguably humbling and depressing—thing is that despite our detailed understanding of the mechanics of the disc, despite our collective clinical experience, and despite the dogma out of which we operate, as a scientific matter we have never been able to prove that these clinical features mean that this patient definitely has, or is even significantly more likely to have, discogenic lower back pain. This is a bit astonishing, and most spine doctors still are confident that the research has simply not caught up with our clinical expertise (and this author would count himself among that group), but the fact remains that we don’t have the scientific data to support the notion that Jake in the above scenario has discogenic lower back pain. If we are being academic in our assessment, then we must cede the point that Jake may have discogenic lower back pain, and there is about a 40 % possibility that he does, but he also may have facet joint pain, sacroiliac joint pain, or something else.

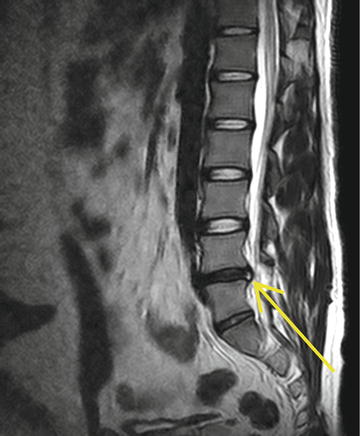

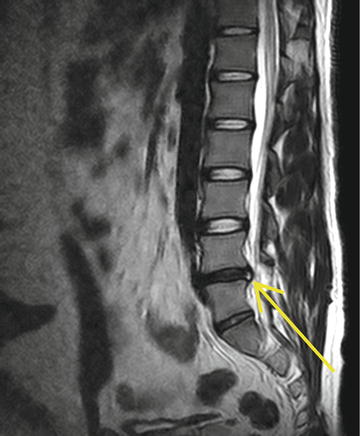

The imaging modality of choice for suspected discogenic lower back pain is an MRI. Given the duration and severity of symptoms, an MRI is indicated for Jake. However, an MRI for discogenic lower back pain is of limited ultimate use [8]. MRIs miss a majority of annular tears in disc and, even if an annular tear is present on MRI, it may not be the cause of pain as asymptomatic annular tears are not uncommon. With that said, if Jake gets an MRI of the lumbosacral spine and the MRI looks normal except for an L5–S1 annular tear, then it would be hard to convince most spine specialists that this is not the cause of the pain. (See Figs. 5.4 and 5.5 for an example of an L4–L5 annular tear as seen on T2-weighted sagittal and axial images.)

Fig. 5.4

T2-weighted sagittal images of an L4–L5 annular tear

Fig. 5.5

T2-weighted axial images of an L4–L5 annular tear

Though, again, if we reverted to evidence-based medicine, we would have to acknowledge that even in Jake’s case, with an annular tear at L5–S1, we still could not draw the conclusion that Jake has discogenic lower back pain. We could posit that Jake seems to belong to the 40 % of cases of patients with chronic lower back pain who turn out to have discogenic lower back pain. We could even posit that every indicator confirms that the disc is the source of pain. However, to say that Jake has discogenic lower back pain based on scientific data, we must wait for a paper or series of papers that shows that Jake’s features predicts true discogenic lower back pain.

If an MRI is not the gold standard diagnostic for discogenic lower back pain, then what is? For reasons that will become evident, this question will be dealt with after discussing the conservative care for presumptive discogenic lower back pain.

In suspected discogenic lower back pain, the initial treatment is often empiric and based on history, physical examination, and possibly MRI findings. Treatment typically begins with an extension-biased lumbar stabilization physical therapy program with attention given to hip flexor stretching and hip abductor strengthening. In physical therapy , passive modalities such as soft tissue mobilization, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation may be used to help with immediate symptoms.

Oral medications have a limited role on actually reducing the inflammation in an annular tear because very little of the medication actually reaches the disc. Sustained, high-dosage nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may have a role in reducing the inflammation, but at these dosages the adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and blood pressure generally outweigh any potential small anti-inflammatory effect at the spine. Similarly, oral steroids are very potent and high dosages may reduce the inflammation in the disc, but the many medical drawbacks of sustained or even short-dosage oral steroids generally outweigh any potential gain. Instead, oral anti-inflammatory medications are generally used for pain reduction. Similarly, muscle relaxers , nerve membrane stabilizing medications, and nonnarcotic as well as narcotic medications all may help with symptom management, and the side effects must be weighed against the benefit for each individual patient.

In some patients, clinical examination may reveal a significant amount of overlying myofascial pain and trigger points in the surrounding musculature. In these patients, trigger point injections may be used for temporary pain relief and symptom management. To the extent that oral medications and trigger point injections help with symptom management and enable patients to engage in an active physical therapy program, they may be considered therapeutic and not just palliative.

If symptoms persist then an epidural steroid injection can be performed. The goal of the epidural steroid injection is to reduce the swelling and inflammation from around the disc. There are three routes of administration of medication in an epidural—caudal, interlaminar, and transforaminal.

In a caudal epidural steroid injection , the medicine is delivered into the epidural space via the sacral hiatus. An advantage of the approach is its relative ease of administration. While fluoroscopy is used, this approach can and is used when fluoroscopy is contraindicated or unavailable for whatever reason. However, because the medicine is starting in the sacrum, a much larger volume of medicine must be used in order to reach the lower lumbar segments, and therefore there is a necessary and significant dilution of the steroid in the solution. Sometimes a catheter is inserted via the sacral hiatus in order to better reach the level of pathology and thus not dilute the medication as much.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree