H. Gordon Deen Jr.

Awide range of disease processes may affect the vertebral column of the older adult. The spinal cord, cauda equina, and spinal nerve roots may also be involved. This chapter will provide an overview of these diseases, with an emphasis on the more common disorders that the primary care practitioner or neurologist will be more likely to encounter in clinical practice.

OSTEOPOROSIS

Osteoporosis is a very common problem in the elderly, with an estimated 700,000 new cases per year in the United States alone. Although osteoporosis has received much recent attention in medical publications and in the lay press, this disorder is sometimes underrecognized and undertreated. Osteoporosis is seen more frequently in women but can also occur in men. From a conceptual standpoint, osteoporosis can be defined as a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture. From an operational standpoint, osteoporosis is defined as a bone mineral density (T-score) that is 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the mean peak value in young adults. Patients with osteoporosis can sustain fractures with minimal trauma. The vertebral column, proximal femur, and distal forearm are most commonly involved, but fracture of any bone can occur. Vertebral compression fractures are the most common manifestation of osteoporosis of the spine. The lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae are the most common sites of involvement. A compression fracture above the T7 level is rarely caused by osteoporosis, and the diagnosis of tumor or infection should be considered in such cases.

Osteoporotic spinal compression fractures cause back pain, with or without radiculopathy. Symptoms often respond poorly to treatment. Multiple vertebral fractures occurring over time may lead to secondary spinal disorders such as spinal stenosis, scoliosis, or kyphotic deformity.

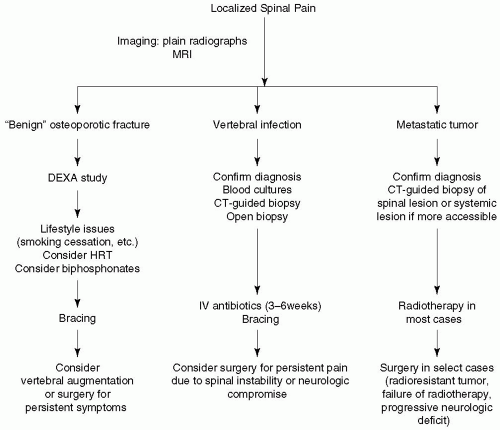

“Benign” osteoporotic compression fracture should be a diagnosis of exclusion (Fig. 24-1). The physician should always consider the possibility that an acute spinal compression fracture may be caused by neoplasm or infection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usually provides some clues in this regard. In osteoporotic spinal compression fractures, the adjacent epidural and paraspinal soft tissues are normal, and the pedicle is not involved. There is usually only one acute fracture; however, there may be old, healed compression fractures in other vertebral bodies. In cases where the fracture is due to metastatic tumor, there are often abnormalities of the adjacent epidural and paraspinal soft tissues and in the pedicle. There are often acute lesions at other levels of the spinal column. In cases where the fracture is due to infection, the abnormalities are centered in the intervertebral disk space. There is abnormal T1 signal in the vertebral bodies, adjacent to the disk. The epidural and paraspinal soft tissues are often involved. In most cases, the MRI, coupled with clinical findings, enables the physician to determine whether the patient has a benign osteoporotic compression fracture or whether a more ominous diagnosis is present. A few patients, initially felt to have benign spinal compression fractures, have persistent or worsening pain or indeterminate MRI findings. These individuals should have a follow-up MRI examination in 6 weeks to 3 months.

When the diagnosis of osteoporosis is suspected, the physician should inquire about risk factors, including family history, cigarette smoking, alcohol abuse, sedentary lifestyle, low body weight, inadequate dietary calcium, low exposure to sunlight, early menopause, and chronic medication therapy with steroids, certain anticonvulsants (phenytoin), and anticoagulants. The physician should also be aware that a variety of endocrine diseases (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome), hematologic diseases (e.g., multiple myeloma), rheumatologic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), and gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., malabsorption syndromes) may be associated with osteoporosis. Radiotherapy that includes the spinal column in the treatment fields may also predispose to loss of skeletal bone mass.

Osteoporosis is now viewed as having primary and secondary forms (7). The typical osteoporosis seen in

elderly women with no other risk factors is referred to as primary osteoporosis. Patients with risk factors such as liver or kidney failure, chronic steroid therapy, and early menopause are said to have secondary osteoporosis. Patients with secondary osteoporosis develop earlier and more severe bony disease than patients with primary osteoporosis.

elderly women with no other risk factors is referred to as primary osteoporosis. Patients with risk factors such as liver or kidney failure, chronic steroid therapy, and early menopause are said to have secondary osteoporosis. Patients with secondary osteoporosis develop earlier and more severe bony disease than patients with primary osteoporosis.

Figure 24-1. Diagnosis algorithm for spinal compression fracture. DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; IV, intravenous. |

Management of osteoporosis involves both prevention and treatment. The physician should first focus on lifestyle issues, emphasizing the importance of smoking cessation and avoidance of excessive alcohol, while encouraging an adequate level of physical exercise and dietary calcium. Patients should be counseled to avoid heavy lifting and to take care to avoid falls. The risk of falling can be decreased by eliminating sedating medications. Some patients may benefit from using a cane or walker. Estrogen replacement therapy is the treatment of choice for women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Other pharmacologic options include bisphosphonates, raloxifene, and calcitonin nasal spray.

An acute osteoporotic spinal compression fracture is managed with short-term activity reduction, analgesics, and bracing. A lightweight corset is better tolerated and less expensive and appears to be as effective as more rigid, custom-made orthoses. Narcotics may be necessary for short-term pain control.

For patients with painful compression fractures, percutaneous vertebral augmentation with either vertebroplasty or balloon kyphoplasty has emerged as a very effective treatment. These procedures involve the percutaneous injection of methylmethacrylate bone cement, under fluoroscopic guidance, into the symptomatic, compressed vertebral body. The difference between the two techniques is that balloon kyphoplasty involves inflation of a balloon tamp in the compressed vertebral body. This creates a cavity in the bone, which permits a low-pressure injection of bone cement with less risk of cement extravasation and embolus. In some cases, balloon inflation also helps restore spinal alignment. Local anesthesia plus intravenous sedation or a light general anesthetic may be used. The procedures typically require just an overnight stay in the hospital and may sometimes be performed on an outpatient basis.

Experience accumulated over the last decade indicates that the procedure can be done safely, with excellent short-term pain relief. Patients are still at risk for fractures at other levels, and this possibility should be kept in mind if a patient develops new pain after a successful vertebral augmentation procedure. Refracture of a treated level is uncommon. Vertebral augmentation is contraindicated if there is significant compromise of the spinal canal from retropulsion of compressed bone fragments.

Open surgery is usually not needed for osteoporotic spinal compression fractures. An occasional patient with significant spinal canal compromise and myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome will need to be considered for spinal canal decompression and stabilization via anterior and/or posterior surgical approaches. Unfortunately, these surgical procedures are often lengthy and complex, with the potential for significant blood loss and other complications. Prolonged hospital care and rehabilitation may be required. Furthermore, the patients who harbor osteoporotic compression fractures are often elderly and debilitated. Therefore, a decision to intervene with major reconstructive surgery should not be taken lightly by the physician or the patient.

SPINAL METASTATIC TUMOR

The diagnosis of spinal metastatic tumor should be strongly considered in the older adult who presents with acute, severe spinal pain. The patient typically reports intense, localized, persistent pain at the level of the lesion. The pain is often worse at night. There may be a wide range of neurologic involvement. The patient may have a monoradiculopathy, myelopathy, or cauda equina syndrome from neural compression. Some patients have no neurologic symptoms or signs, whereas others present with a rapidly progressive, severe neurologic deficit. Some patients have an established diagnosis of systemic cancer, whereas many others do not. The physician should be aware that the metastatic component of a tumor may cause symptoms before the primary tumor. For example, a patient with carcinoma of the lung may present with spinal metastasis, with the primary lesion being discovered only during subsequent evaluation. The physician will also encounter an occasional patient with spinal metastatic cancer, in whom a primary tumor is never identified despite aggressive workup. Metastases account for 70% of all tumors of the spine. The most common primary tumor types are carcinoma of the breast, carcinoma of the lung, lymphoma, and carcinoma of the prostate. Carcinoma of the kidney and colon and a wide range of less common tumors may also have metastatic involvement of the spinal column.

Plain radiographs of the spine still play a useful role in the evaluation of spinal metastatic disease. The first radiographic evidence of spinal metastasis is the “winking owl” sign caused by obliteration of the pedicle. Spinal compression fractures may be seen. These lesions may be osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed. Carcinoma of the prostate and Hodgkin’s disease are known to cause osteoblastic bony changes with the so-called “ivory vertebrae.” MRI is more sensitive than plain radiographs and should be performed whenever spinal metastasis is a diagnostic possibility. MRI shows bony lesions before they become apparent on plain radiographs and also reveals their soft tissue components, epidural spread, and neural compromise. Patients with spinal metastatic disease often have involvement of multiple spinal segments. Therefore, if one lesion is identified, the clinician must diligently search for lesions at other levels.

Spinal metastatic tumors are almost always extradural in location. Intradural metastases from primary brain tumors, such as glioblastoma multiforme and medulloblastoma, are uncommon. These so-called “drop metastases” have a characteristic MRI appearance of multiple nodules on the spinal cord and cauda equina. Intramedullary metastasis of non-central nervous system tumors into the substance of the spinal cord is rare. The lesion is usually well seen on MRI. These cases are characterized by rapid neurologic deterioration. Prognosis is poor.

The mainstay of treatment is radiotherapy of the involved spinal segments. Surgery is reserved for patients harboring tumors known to be radiotherapy resistant, patients with a rapidly progressive neurologic deficit or severe pain, and patients who have failed radiation therapy. A surgical approach may also be necessary to obtain diagnostic tissue in the occasional patient in whom the diagnosis is uncertain. Laminectomy as a stand-alone procedure is seldom indicated. Surgical treatment usually involves both decompression and stabilization from anterior or posterior (or combined) surgical approaches.

Vertebral augmentation may be a useful option for patients with pathologic compression fractures secondary to metastatic disease (5). Similar to benign fractures, pain relief is generally excellent in patients with pathologic fractures. Vertebral augmentation has the added advantage of permitting prompt radiotherapy after the procedure, in contrast to open surgery that mandates several weeks of wound healing before radiotherapy can be started.

Prognosis depends on the biologic activity of the underlying neoplasm. For example, spinal metastasis from carcinoma of the prostate often pursues an indolent course with little morbidity. In contrast, spinal metastasis from carcinoma of the lung carries a poorer prognosis. Outcome is variable with multiple myeloma.

Some patients with this disease have a rapidly progressive downhill course, whereas others have prolonged survival for 5 years or more. Prognosis also depends on whether the spinal lesions are single or multiple and on whether there is any neurologic involvement. An isolated spinal metastatic lesion without neurologic compromise can generally be controlled with radiotherapy and surgery, provided the malignancy is not progressing elsewhere in the body. In contrast, the prognosis is much worse in patients with multiple spinal metastases and significant cord compression and in patients with rapidly progressive extraspinal disease.

Some patients with this disease have a rapidly progressive downhill course, whereas others have prolonged survival for 5 years or more. Prognosis also depends on whether the spinal lesions are single or multiple and on whether there is any neurologic involvement. An isolated spinal metastatic lesion without neurologic compromise can generally be controlled with radiotherapy and surgery, provided the malignancy is not progressing elsewhere in the body. In contrast, the prognosis is much worse in patients with multiple spinal metastases and significant cord compression and in patients with rapidly progressive extraspinal disease.

PRIMARY BONE TUMORS AFFECTING THE SPINE

A number of primary bone tumors can be found in the spinal column. In contrast to metastatic tumors, primary bone tumors of the spine are uncommon and are seen infrequently, even by spinal surgeons. These lesions may be benign or malignant. Benign tumors include osteochondroma, osteoid osteoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, hemangioma, giant cell tumor, and eosinophilic granuloma. Malignant tumors include chordoma, sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma.

Similar to spinal metastases, the hallmark of primary bone tumors of the spine is intractable pain. Neurologic deficits due to neural compression may also be present. Treatment usually involves radical surgery using anterior or posterior or combination approaches. Postoperative radiotherapy may be needed in selected cases.

SPINAL INTRADURAL TUMORS

A wide variety of tumors and other mass lesions can occur within the spinal dura. Most are uncommon in the elderly and will rarely be encountered by the primary care physician. Even a neurologist or neurosurgeon will see only a handful of these cases each year.

Lesions arising within the substance of the spinal cord are referred to as intramedullary tumors (4). All other intradural tumors are considered to be intradural, extramedullary in location. This includes tumors of the spinal nerve roots, cauda equina, and meninges.

The most common intramedullary tumors are ependymoma and astrocytoma. Less common lesions include hemangioblastoma, lipoma, and metastasis. Nonneoplastic mass lesions are occasionally seen in the cord, including cavernoma, epidermoid cyst, neuroglial cyst, and sarcoid granuloma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree